Orangutan Call Communication and the Puzzle of Speech Evolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Circus Friends Association Collection Finding Aid

Circus Friends Association Collection Finding Aid University of Sheffield - NFCA Contents Poster - 178R472 Business Records - 178H24 412 Maps, Plans and Charts - 178M16 413 Programmes - 178K43 414 Bibliographies and Catalogues - 178J9 564 Proclamations - 178S5 565 Handbills - 178T40 565 Obituaries, Births, Death and Marriage Certificates - 178Q6 585 Newspaper Cuttings and Scrapbooks - 178G21 585 Correspondence - 178F31 602 Photographs and Postcards - 178C108 604 Original Artwork - 178V11 608 Various - 178Z50 622 Monographs, Articles, Manuscripts and Research Material - 178B30633 Films - 178D13 640 Trade and Advertising Material - 178I22 649 Calendars and Almanacs - 178N5 655 1 Poster - 178R47 178R47.1 poster 30 November 1867 Birmingham, Saturday November 30th 1867, Monday 2 December and during the week Cattle and Dog Shows, Miss Adah Isaacs Menken, Paris & Back for £5, Mazeppa’s, equestrian act, Programme of Scenery and incidents, Sarah’s Young Man, Black type on off white background, Printed at the Theatre Royal Printing Office, Birmingham, 253mm x 753mm Circus Friends Association Collection 178R47.2 poster 1838 Madame Albertazzi, Mdlle. H. Elsler, Mr. Ducrow, Double stud of horses, Mr. Van Amburgh, animal trainer Grieve’s New Scenery, Charlemagne or the Fete of the Forest, Black type on off white backgound, W. Wright Printer, Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, 205mm x 335mm Circus Friends Association Collection 178R47.3 poster 19 October 1885 Berlin, Eln Mexikanermanöver, Mr. Charles Ducos, Horaz und Merkur, Mr. A. Wells, equestrian act, C. Godiewsky, clown, Borax, Mlle. Aguimoff, Das 3 fache Reck, gymnastics, Mlle. Anna Ducos, Damen-Jokey-Rennen, Kohinor, Mme. Bradbury, Adgar, 2 Black type on off white background with decorative border, Druck von H. G. -

The Use of Non-Human Primates in Research in Primates Non-Human of Use The

The use of non-human primates in research The use of non-human primates in research A working group report chaired by Sir David Weatherall FRS FMedSci Report sponsored by: Academy of Medical Sciences Medical Research Council The Royal Society Wellcome Trust 10 Carlton House Terrace 20 Park Crescent 6-9 Carlton House Terrace 215 Euston Road London, SW1Y 5AH London, W1B 1AL London, SW1Y 5AG London, NW1 2BE December 2006 December Tel: +44(0)20 7969 5288 Tel: +44(0)20 7636 5422 Tel: +44(0)20 7451 2590 Tel: +44(0)20 7611 8888 Fax: +44(0)20 7969 5298 Fax: +44(0)20 7436 6179 Fax: +44(0)20 7451 2692 Fax: +44(0)20 7611 8545 Email: E-mail: E-mail: E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Web: www.acmedsci.ac.uk Web: www.mrc.ac.uk Web: www.royalsoc.ac.uk Web: www.wellcome.ac.uk December 2006 The use of non-human primates in research A working group report chaired by Sir David Weatheall FRS FMedSci December 2006 Sponsors’ statement The use of non-human primates continues to be one the most contentious areas of biological and medical research. The publication of this independent report into the scientific basis for the past, current and future role of non-human primates in research is both a necessary and timely contribution to the debate. We emphasise that members of the working group have worked independently of the four sponsoring organisations. Our organisations did not provide input into the report’s content, conclusions or recommendations. -

Animal Representations, Anthropomorphism, and Några Tillfällen – Kommer Frågan Om Subjektivi- Interspecies Relations in the Little Golden Books

Samlaren Tidskrift för forskning om svensk och annan nordisk litteratur Årgång 139 2018 I distribution: Eddy.se Svenska Litteratursällskapet REDAKTIONSKOMMITTÉ: Berkeley: Linda Rugg Göteborg: Lisbeth Larsson Köpenhamn: Johnny Kondrup Lund: Erik Hedling, Eva Hættner Aurelius München: Annegret Heitmann Oslo: Elisabeth Oxfeldt Stockholm: Anders Cullhed, Anders Olsson, Boel Westin Tartu: Daniel Sävborg Uppsala: Torsten Pettersson, Johan Svedjedal Zürich: Klaus Müller-Wille Åbo: Claes Ahlund Redaktörer: Jon Viklund (uppsatser) och Sigrid Schottenius Cullhed (recensioner) Biträdande redaktör: Niclas Johansson och Camilla Wallin Bergström Inlagans typografi: Anders Svedin Utgiven med stöd av Vetenskapsrådet Bidrag till Samlaren insändes digitalt i ordbehandlingsprogrammet Word till [email protected]. Konsultera skribentinstruktionerna på sällskapets hemsida innan du skickar in. Sista inläm- ningsdatum för uppsatser till nästa årgång av Samlaren är 15 juni 2019 och för recensioner 1 sep- tember 2019. Samlaren publiceras även digitalt, varför den som sänder in material till Samlaren därmed anses medge digital publicering. Den digitala utgåvan nås på: http://www.svelitt.se/ samlaren/index.html. Sällskapet avser att kontinuerligt tillgängliggöra även äldre årgångar av tidskriften. Svenska Litteratursällskapet tackar de personer som under det senaste året ställt sig till för- fogande som bedömare av inkomna manuskript. Svenska Litteratursällskapet PG: 5367–8. Svenska Litteratursällskapets hemsida kan nås via adressen www.svelitt.se. isbn 978–91–87666–38–4 issn 0348–6133 Printed in Lithuania by Balto print, Vilnius 2019 Recensioner av doktorsavhandlingar · 241 vitet. Men om medier, med Marshall McLuhan, Kelly Hübben, A Genre of Animal Hanky-panky? är proteser – vilket Gardfors skriver under på vid Animal Representations, Anthropomorphism, and några tillfällen – kommer frågan om subjektivi- Interspecies Relations in The Little Golden Books. -

Williams Dissertation

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Don't Show A Hyena How Well You Can Bite: Performance, Race and the Animal Subaltern in Eastern Africa Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0jf3488f Author Williams, Joshua Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Don’t Show A Hyena How Well You Can Bite: Performance, Race and the Animal Subaltern in Eastern Africa by Joshua Drew Montgomery Williams A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Catherine Cole, Chair Professor Donna Jones Professor Samera Esmeir Professor Brandi Wilkins Catanese Spring 2017 Abstract Don’t Show A Hyena How Well You Can Bite: Performance, Race and the Animal Subaltern in Eastern Africa by Joshua Drew Montgomery Williams Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Catherine Cole, Chair This dissertation explores the mutual imbrication of race and animality in Kenyan and Tanzanian politics and performance from the 1910s through to the 1990s. It is a cultural history of the non- human under conditions of colonial governmentality and its afterlives. I argue that animal bodies, both actual and figural, were central to the cultural and -

Learned Vocal and Breathing Behavior in an Enculturated Gorilla

Anim Cogn (2015) 18:1165–1179 DOI 10.1007/s10071-015-0889-6 ORIGINAL PAPER Learned vocal and breathing behavior in an enculturated gorilla 1 2 Marcus Perlman • Nathaniel Clark Received: 15 December 2014 / Revised: 5 June 2015 / Accepted: 16 June 2015 / Published online: 3 July 2015 Ó Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2015 Abstract We describe the repertoire of learned vocal and relatively early into the evolution of language, with some breathing-related behaviors (VBBs) performed by the rudimentary capacity in place at the time of our last enculturated gorilla Koko. We examined a large video common ancestor with great apes. corpus of Koko and observed 439 VBBs spread across 161 bouts. Our analysis shows that Koko exercises voluntary Keywords Breath control Á Gorilla Á Koko Á Multimodal control over the performance of nine distinctive VBBs, communication Á Primate vocalization Á Vocal learning which involve variable coordination of her breathing, lar- ynx, and supralaryngeal articulators like the tongue and lips. Each of these behaviors is performed in the context of Introduction particular manual action routines and gestures. Based on these and other findings, we suggest that vocal learning and Examining the vocal abilities of great apes is crucial to the ability to exercise volitional control over vocalization, understanding the evolution of human language and speech particularly in a multimodal context, might have figured since we diverged from our last common ancestor. Many theories on the origins of language begin with two basic premises concerning the vocal behavior of nonhuman pri- mates, especially the great apes. They assume that (1) apes (and other primates) can exercise only negligible volitional control over the production of sound with their vocal tract, and (2) they are unable to learn novel vocal behaviors beyond their species-typical repertoire (e.g., Arbib et al. -

LING 001 Introduction to Linguistics

LING 001 Introduction to Linguistics Lecture #6 Animal Communication 2 02/05/2020 Katie Schuler Announcements • Exam 1 is next class (Monday)! • Remember there are no make-up exams (but your lowest exam score will be dropped) How to do well on the exam • Review the study guides • Make sure you can answer the practice problems • Come on time (exam is 50 minutes) • We MUST leave the room for the next class First two questions are easy Last time • Communication is everywhere in the animal kingdom! • Human language is • An unbounded discrete combinatorial system • Many animals have elements of this: • Honeybees, songbirds, primates • But none quite have language Case Study #4: Can Apes learn Language? Ape Projects • Viki (oral production) • Sign Language: • Washoe (Gardiner) (chimp) • Nim Chimpsky (Terrace) (chimp) • Koko (Patterson) (gorilla) • Kanzi (Savage-Rumbaugh) (bonobo) Viki’s `speech’ • Raised by psychologists • Tried to teach her oral language, but didn’t get far... Later Attempts • Later attempts used non-oral languages — • either symbols (Sarah, Kanzi) or • ASL (Washoe, Koko, Nim). • Extensive direct instruction by humans. • Many problems of interpretation and evaluation. Main one: is this a • miniature/incipient unbounded discrete combinatorial system, or • is it just rote learning+randomness? Washoe and Koko Video Washoe • A chimp who was extensively trained to use ASL by the Gardners • Knew 132 signs by age 5, and over 250 by the end of her life. • Showed some productive use (‘water bird’) • And even taught her adopted son Loulis some signs But the only deaf, native signer on the team • ‘Every time the chimp made a sign, we were supposed to write it down in the log… They were always complaining because my log didn’t show enough signs. -

Unit 5/Week 4 Title: Koko's Kitten Suggested Time

McGraw-Hill Open Court - 2002 Grade 4 Unit 5/Week 4 Title: Koko’s Kitten Suggested Time: 5 days (45 minutes per day) Common Core ELA Standards: RI.4.1, RI.4.2, RI.4.3, RI.4.4; RF.4.4; W.4.2, W.4.4, W.4.7, W.4.9; SL.4.1; L.4.1, L.4.2, L.4.4 Teacher Instructions Refer to the Introduction for further details. Before Teaching 1. Read the Big Ideas and Key Understandings and the Synopsis. Please do not read this to the students. This is a description for teachers, about the big ideas and key understanding that students should take away after completing this task. Big Ideas and Key Understandings Animals are capable of experiencing the same feelings as human beings; desire, disappointment, love, nurturing, and sadness. They are also capable of making important connections with other living things. Synopsis Koko’s Kitten is the story of Koko, a gorilla, who longs to have a kitten as her “baby.” Koko is able to communicate her feelings to her trainer, Dr. Patterson and the assistants through sign language. After some time, she gets her kitten. Koko treats the kitten as her baby and loves and nurtures him. The kitten grows and one day gets hit by a car. This event upsets Koko but after some time, Koko gets another kitten to love and care for. 2. Read entire main selection text, keeping in mind the Big Ideas and Key Understandings. 3. Re-read the main selection text while noting the stopping points for the Text Dependent Questions and teaching Vocabulary. -

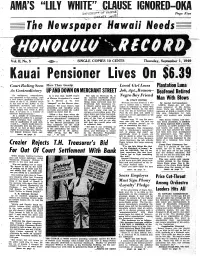

HONOLULU.Rtcord

AMA’S “LILY WHITE” CLAUSE IGNORED -OKA Of HAM • • Page Five ^The Newspaper Hawaii Needs HONOLULU.RtCORD. Vol. II, No. 5 SINGLE COPIES 10 CENTS Thursday, September 1, 1949 Kauai Pensioner Lives On $6.39 Court R uling Seen More Than Gossip: Local Girl Loses Plantation Luna As Contradictory UP AND DOWN ON MERCHANT STREET Job,Apt^Reason-- Deafened Retired “So ambiguous, contradictory, Is it true that 125,000 shares The talk on Merchant St. is Negro Boy Friend and uncertain is this ruling,” says of Matson Navigation Co. owned the reported $40,000,000 which a local lawyer, speaking of the' de the California and Hawaiian Re By STAFF WRITER Man With Blows cision of the U. S. District Court by C. Brewer & Co. were fining Corp, borrowed from the “dumped” on the Brewer plan Because her boy friend is a Ne By Special Correspondence in the case-of-the ILWU vs. the Prudential Life Insurance Co. gro—a soldier and a veteran of legislature, governor and others, tations? We hear there’s loud LIHUE, Kauai—An old Jap A reliable source says that this action in Germany in World War anese pensioner of the Koloa- “that it can be interpreted only grumbling and rumbling going money paid for two-thirds of II—Sharon Wiechel, 22, was fired by the judges who wrote it. Even on inside and outside the walled this year’s sugar crop now in Grove Farm was retired by the then, it is* open to a number of citadel on lower Fort St. from her job at American Legion company: at,$14.04 a month. -

Koko Communicates

LESSON 11 TEACHER’S GUIDE Koko Communicates by Justin Marciniak Fountas-Pinnell Level O Narrative Nonfiction Selection Summary Koko the gorilla was taught to “speak” an astonishing 1,000-plus words in sign language by Penny, her human caregiver. Koko signs her thoughts, feelings, and even made-up insults. She has two gorilla friends who also sign, and a kitten she named “Smoke.” Number of Words: 822 Characteristics of the Text Genre • Narrative nonfi ction Text Structure • Third-person narrative in fi ve chronological sections Content • Koko and gorilla behavior; teaching Koko sign language • American Sign Language • Koko’s life and her human and animal companions Themes and Ideas • Animals and people can learn from each other. • Animals can think, feel, communicate, invent, and learn. • Animals and their human caregivers develop close bonds. Language and • Informal narrative between gorillas Literary Features • Narrative presents most information in chronological fashion Sentence Complexity • Mix of complex sentences and simple sentences • Items in a series • Words in quotation marks, dashes, italics, parentheses Vocabulary • Words and phrases associated with zoos and biologists: western lowland gorilla, biological, assistants, researchers Words • Multisyllable words, such as communicates, university, disciplined, biological • Hyphenated words, such as one-year-old, three-year-old, hide-and-seek, reddish-orange Illustrations • Photographs with captions, charts, sidebars Book and Print Features • Twelve pages of text, most with illustrations -

Orofacial-Motor and Breath Control in Chimpanzees and Bonobos Natalie Schwob

Kennesaw State University DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Organismal Master of Science in Integrative Biology Theses Biology Summer 7-28-2017 Evidence of Language Prerequisites in Pan: Orofacial-Motor and Breath Control in Chimpanzees and Bonobos Natalie Schwob Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/integrbiol_etd Part of the Integrative Biology Commons Recommended Citation Schwob, Natalie, "Evidence of Language Prerequisites in Pan: Orofacial-Motor and Breath Control in Chimpanzees and Bonobos" (2017). Master of Science in Integrative Biology Theses. 25. http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/integrbiol_etd/25 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Organismal Biology at DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Science in Integrative Biology Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Evidence of Language Prerequisites in Pan: Orofacial-Motor and Breath Control in Chimpanzees and Bonobos Natalie Schwob Kennesaw State University Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Organismal Biology Master of Science in Integrative Biology Thesis Advisor: Jared P. Taglialatela, PhD Thesis Committee Members: Marcus Davis, PhD and Joel McNeal, PhD Kennesaw e1( JNIVERSJITY -ireete liege / i3e i:afiut Deffnsc outcome Neme L KSU ID Emit ee jy Phone Number Lte2. çL1 Program -

Bonobos and Chimpanzees: How Similar Is Their Cognition and Temperament? a Large, Continuous, and Stable Population of Eastern C

window, the owner removed the monkey seconds after the killing and thus the eating of the prey was interrupted. Here, we report that pygmy marmosets in the Kristiansand Zoo in Norway reg- ularly kill and eat different species of healthy, free-living birds. We present what, to our knowl- edge, are the first systematic data collected on this behaviour. We describe the patterns of bird consumption by the monkeys. Pygmy marmosets are the smallest monkey species and thus their bird hunting behaviour is especially interesting since they are about the same size as the birds they prey upon. It has been proposed that humans are unique among primates for their ability to hunt prey that equals or exceeds their own body size. We discuss the implications that hunting of prey of equal body size by pygmy marmosets has for human evolution. Bonobos and Chimpanzees: How Similar Is Their Cognition and Temperament? Esther Herrmann Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany E-Mail: eherrman @ eva.mpg.de Key Words: Cognition · Temperament · Chimpanzees · Bonobos Despite the evolutionary closeness of bonobos (Pan paniscus) and chimpanzees (Pan tro- glodytes) , the behaviour of these two Pan species differs in crucial ways. A few key differences were revealed when both species were compared on a wide range of cognitive problems testing their understanding of the physical and social world (Herrmann et al., 2010). The tests of physi- cal cognition consisted of problems concerning space, quantity, tools and causality, while those of social cognition covered social learning, communication, and Theory of Mind tasks. A further comparison of bonobos and chimpanzees in two main temperamental components, reactivity and self-regulation (Rothbart and Derryberry, 1981), was conducted to investigate other possible species differences. -

Planum Parietale of Chimpanzees and Orangutans: a Comparative Resonance of Human-Like Planum Temporale Asymmetry

THE ANATOMICAL RECORD PART A 287A:1128–1141 (2005) Planum Parietale of Chimpanzees and Orangutans: A Comparative Resonance of Human-Like Planum Temporale Asymmetry 1 2 3 PATRICK J. GANNON, * NANCY M. KHECK, ALLEN R. BRAUN, AND RALPH L. HOLLOWAY4 1Department of Otolaryngology, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York 2Department of Medical Education, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York 3National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, Bethesda, Maryland 4Department of Anthropology, Columbia University, New York, New York ABSTRACT We have previously demonstrated that leftward asymmetry of the planum temporale (PT), a brain language area, was not unique to humans since a similar condition is present in great apes. Here we report on a related area in great apes, the planum parietale (PP). PP in humans has a rightward asymmetry with no correlation to the LϾR PT, which indicates functional independence. The roles of the PT in human language are well known while PP is implicated in dyslexia and communication disorders. Since posterior bifurcation of the syl- vian fissure (SF) is unique to humans and great apes, we used it to determine characteristics of its posterior ascending ramus, an indicator of the PP, in chimpanzee and orangutan brains. Results showed a human-like pattern of RϾLPP(P ϭ 0.04) in chimpanzees with a nonsig- nificant negative correlation of LϾR PT vs. RϾLPP(CCϭϪ0.3; P ϭ 0.39). In orangutans, SF anatomy is more variable, although PP was nonsignificantly RϾL in three of four brains (P ϭ 0.17).