Disease and the Practices of Settlement in a Plantation Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on Naxalbari Struggle

r I REPORT ON NAXALBARI STRUGGLE DEVELOP PEASAKTS' CLASS STRUGGLE FOLLOW THE RoAD OF THE OCTOBER REVOLUTION MARXISM-LENINISM & THOUGHT OF MAO TSE.TUNG ARE 'ONE FIGHT IMPERIALISM, FIGHT REVISIONISM COMMUNIST REVOLUTIONARIES MEET Vol. 2, No.1 November 19ti8 LIBERATION Notes: 3 -One Eventful Year -Follow the Road of the Octobe1"Revolution -Reaction's Offensive -"Problems Ahead for Vietnam" The People Are Rising In Rebellion 16 Develop Peasants' Class Struggle Through Class Analysis, Investigation and Study-Charu Mazumdar 17 Soviet Revisionists-Enemies of Soviet Workers 21 Communist Revolutionaries Meet 22 Lackeys of Indian Reaction 27 Report On the Peasant Movement In the Terai Region-Kanu Sanyal 28 Resolution Adopted At the Convention of Revolutionary Peasants 54 Advance Courageously Along the Road of Triumph-People's Daily, Red Flag and Liberation Army Daily 56 To Fight Imperialism It Is Necessary To Fight Revisionism-M. L. 63 Marxism-Leninism and Thought of Mao Tse-tung Are One-Asit Sen 74 Editor-in-Chief Susbital Ray Cbaudhury L 1 :MOTES 6 LIBERATION important strategically, due to revisionist cODspiracies' tiona.ry parties is almost complete, the sham communists, but in the world as a whole the revolutionary' tide will~ Marxists and socialists 'of various brands have stepped far from receding, continue to advance. Before it the into' the breach to stabilise the present system, as E. M. S.' worl<i-wide front set up by the imperialists, revisionists Na.mboodiripad himself said in his interview with the and other reactionaries to oppose the new world front Washington Post correspondent ( see People's Democracy, of revolution led by Socialist China and Socialist Albania January 14, 1968). -

The Land in Gorkhaland on the Edges of Belonging in Darjeeling, India

The Land in Gorkhaland On the Edges of Belonging in Darjeeling, India SARAH BESKY Department of Anthropology and Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, Brown University, USA Abstract Darjeeling, a district in the Himalayan foothills of the Indian state of West Bengal, is a former colonial “hill station.” It is world famous both as a destination for mountain tour- ists and as the source of some of the world’s most expensive and sought-after tea. For deca- des, Darjeeling’s majority population of Indian-Nepalis, or Gorkhas, have struggled for sub- national autonomy over the district and for the establishment of a separate Indian state of “Gorkhaland” there. In this article, I draw on ethnographic fieldwork conducted amid the Gorkhaland agitation in Darjeeling’s tea plantations and bustling tourist town. In many ways, Darjeeling is what Val Plumwood calls a “shadow place.” Shadow places are sites of extraction, invisible to centers of political and economic power yet essential to the global cir- culation of capital. The existence of shadow places troubles the notion that belonging can be “singularized” to a particular location or landscape. Building on this idea, I examine the encounters of Gorkha tea plantation workers, students, and city dwellers with landslides, a crumbling colonial infrastructure, and urban wildlife. While many analyses of subnational movements in India characterize them as struggles for land, I argue that in sites of colonial and capitalist extraction like hill stations, these struggles with land are equally important. In Darjeeling, senses of place and belonging are “edge effects”:theunstable,emergentresults of encounters between materials, species, and economies. -

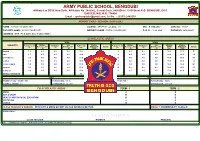

VIII-B-Report-Card.Pdf

ARMY PUBLIC SCHOOL, BENGDUBI Affiliated to CBSE New Delhi, Affiliation No. 2480002, School Code. 8406(Old) / 19155(New) P.O. BENGDUBI, DIST. DARJEELING, W.B.-734424 Email -: [email protected], Tel No. -: (0353) 2480238 REPORT CARD - SESSION ( 2019-2020 ) NAME : AAYUSH CHOUDHARY COURSE : GENERAL - CLASS : VIII SEC : B -ROLLNo:1 ADM. NO. : 13387 FATHER'S NAME : NK SK CHOUDHARY MOTHER'S NAME : PUTUL CHOUDHARY D. O. B. : 10-02-2007 PHONE NO. 9474099811 ADDRESS : QTR 176 E ZONE DELHI DELHI INDIA SCHOLASTIC AREAS TERM 1 TERM 2 SUBJECTS Multiple Sub Marks Multiple Sub ANNUAL Marks Periodic Test-1 Assessment-1 Portfolio-1 Enrichment-1 Half Yearly Obtained Grade Periodic Test-2 Assessment-2 Portfolio-2 Enrichment-2 EXAM Obtained Grade ( 5 ) ( 5 ) ( 5 ) ( 5 ) ( 80 ) (100) ( 5 ) ( 5 ) ( 5 ) ( 5 ) ( 80 ) (100) ENGLISH 1.9 4.0 4.0 5.0 32.0 46.9 C2 1.3 4.0 4.0 4.0 14.0 27.3 E HINDI 1.7 4.5 4.5 4.5 28.0 43.2 C2 1.8 4.5 4.5 4.5 29.0 44.3 C2 MATHEMATICS 2.9 4.0 4.0 4.0 27.0 41.9 C2 2.0 4.0 4.0 4.0 41.0 55.0 C1 SCIENCE 2.5 4.0 4.5 4.0 35.0 50.0 C2 1.9 4.0 4.0 4.0 33.5 47.4 C2 SOCIAL SCIENCE 3.0 5.0 4.0 4.5 31.0 47.5 C2 3.4 5.0 5.0 5.0 54.0 72.4 B1 SANSKRIT 3.0 5.0 5.0 5.0 21.0 39.0 D 2.4 4.5 4.5 4.5 39.0 54.9 C1 COMPUTER 2.0 4.5 4.5 4.5 47.0 62.5 B2 2.1 4.5 4.5 4.5 47.0 62.6 B2 GENERAL KNOWLEDGE * B A TERM 1 TERM 2 GRAND TOTAL - 331.00 / 700 PERCENTAGE - 47.3% GRAND TOTAL - 363.90 / 700 PERCENTAGE - 52.0% OVERALL GRADE - C2 ATTENDANCE - 98 / 101 OVERALL GRADE - C1 ATTENDANCE - 212 / 223 CO-SCHOLASTIC AREAS TERM - 1 TERM - 2 MUSIC A B ART & CRAFT B B HEALTH AND PHYSICAL EDUCATION B B DISCIPLINE A A DANCE B B CLASS TEACHER'S REMARK : WITH LITTLE MORE EFFORT HE CAN DO MUCH BETTER. -

Village & Town Directory ,Darjiling , Part XIII-A, Series-23, West Bengal

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SERmS 23 'WEST BENGAL DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PART XIll-A VILLAGE & TO"WN DIRECTORY DARJILING DISTRICT S.N. GHOSH o-f the Indian Administrative Service._ DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS WEST BENGAL · Price: (Inland) Rs. 15.00 Paise: (Foreign) £ 1.75 or 5 $ 40 Cents. PuBLISHED BY THB CONTROLLER. GOVERNMENT PRINTING, WEST BENGAL AND PRINTED BY MILl ART PRESS, 36. IMDAD ALI LANE, CALCUTTA-700 016 1988 CONTENTS Page Foreword V Preface vn Acknowledgement IX Important Statistics Xl Analytical Note 1-27 (i) Census ,Concepts: Rural and urban areas, Census House/Household, Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes, Literates, Main Workers, Marginal Workers, N on-Workers (ii) Brief history of the District Census Handbook (iii) Scope of Village Directory and Town Directory (iv) Brief history of the District (v) Physical Aspects (vi) Major Characteristics (vii) Place of Religious, Historical or Archaeological importance in the villages and place of Tourist interest (viii) Brief analysis of the Village and Town Directory data. SECTION I-VILLAGE DIRECTORY 1. Sukhiapokri Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 31 (b) Village Directory Statement 32 2. Pulbazar Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 37 (b) Village Directory Statement 38 3. Darjiling Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 43 (b) Village Directory Statement 44 4. Rangli Rangliot Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 49- (b) Village Directory Statement 50. 5. Jore Bungalow Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 57 (b), Village Directory Statement 58. 6. Kalimpong Poliee Station (a) Alphabetical list of viI1ages 62 (b)' Village Directory Statement 64 7. Garubatban Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 77 (b) Village Directory Statement 78 [ IV ] Page 8. -

Darjeeling Himalayan Railway

ISSUE ONE Darjeeling Himalayan Railway - a brief description Locomotive availability News from the line Chunbhati loop 1943 Birth of the Darjeeling Railway Agony Point, sometime around the 1930's Chunbhati loop - an early view Above the clouds Darjeeling Himalayan Railway Society ISSUE TWO News from the line Darjeeling, past and present Darjeeling station Streamliner Himalayan Mysteries The Causeway Incident Tour to the DHR A Way Forward ISSUE THREE News from the line To Darjeeling - February 98 Locomotive numbers Timetable Vacuum Brakes To Darjeeling in 1966 Darjeeling or Bust Covered Wagons ISSUE FOUR Report: Visit to India in September 1998 Going Loopy (part 1) Loop No1 Loop No2 Chunbhati loop Streamliner (part 2) Jervis Bay Darjeeling's history To School in Darjeeling ISSUE FIVE News from the line Going Loopy (part 2) Batasia loop Gradient profile Riyang station Zigzag No1 In Search of the Darjeeling Tanks Gillanders Arbuthnot & Co Tank Wagon ISSUE SIX News from the line Repairing the breach Going Loopy (part 3) Loop No2 Zigzag No1 to No 6 Tour - the DHRS Measuring a railway curve David Barrie Bullhead rail ISSUE SEVEN News from the line First impressions Bogies Bogie drawing New Jalpaiguri Locomotive and carriage sheds New Jalpaiguri Depot Going Loopy (part 4) Witch of Ghoom Colliery Engines Buffing gear ISSUE EIGHT May 2000 celebrations News from the line Best Kept Station Competition Impressions of Darjeeling - Mary Stickland Tindharia (part1) Tindharia Works Garratt at Chunbhati Going Loopy – Postscript In And Around Darjeeling -

West Bohemian Historical Review VIII 2018 2 | |

✐ ✐ ✐ ✐ West Bohemian Historical Review VIII 2018 2 | | Editors-in-Chief LukášNovotný (University of West Bohemia) Gabriele Clemens (University of Hamburg) Co-editor Roman Kodet (University of West Bohemia) Editorial board Stanislav Balík (Faculty of Law, University of West Bohemia, Pilsen, Czech Republic) Gabriele Clemens (Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany) Radek Fukala (Faculty of Philosophy, J. E. PurkynˇeUniversity, Ústí nad Labem, Czech Republic) Frank Golczewski (Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany) Michael Gehler (Faculty of Educational and Social Sciences, University of Hildesheim, Hildesheim, Germany) László Gulyás (Institute of Economy and Rural Development, University of Szeged, Szeged, Hungary) Arno Herzig (Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany) Hermann Joseph Hiery (Faculty of Cultural Studies, University of Bayreuth, Bayreuth, Germany) Václav Horˇciˇcka (Faculty of Arts, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic) Drahomír Janˇcík (Faculty of Arts, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic) ZdenˇekJirásek (Faculty of Philosophy and Sciences, Silesian University, Opava, Czech Republic) ✐ ✐ ✐ ✐ ✐ ✐ ✐ ✐ Bohumil Jiroušek (Faculty of Philosophy, University of South Bohemia, Ceskéˇ Budˇejovice,Czech Republic) Roman Kodet (Faculty of Arts, University of West Bohemia, Pilsen, Czech Republic) Martin Kováˇr (Faculty of Arts, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic) Hans-Christof Kraus (Faculty of Arts and Humanities, University of Passau, -

Land Tenures in Cooch Behar District, West Bengal: a Study of Kalmandasguri Village Ranjini Basu*

RESEARCH ARTICLE Land Tenures in Cooch Behar District, West Bengal: A Study of Kalmandasguri Village Ranjini Basu* Abstract: This paper describes and analyses changes in land tenure in Cooch Behar district, West Bengal. It does so by focussing on land holdings and tenures in one village, Kalmandasguri. The paper traces these changes from secondary historical material, oral accounts, and from village-level data gathered in Kalmandasguri in 2005 and 2010. Specifically, the paper studies the following four interrelated issues: (i) land tenure in the princely state of Cooch Behar; (ii) land tenure in pre-land-reform Kalmandasguri; (iii) the implementation and impact of land reform in Kalmandasguri; and (iv) the challenges ahead with respect to the land system in Kalmandasguri. The paper shows that an immediate, and dramatic, consequence of land reform was to establish a vastly more equitable landholding structure in Kalmandasguri. Keywords: Kalmandasguri, Cooch Behar, West Bengal, sharecropping, princely states, history of land tenure, land reform, village studies, land rights, panel study. Introduction This paper describes and analyses changes in land tenure in Cooch Behar district, West Bengal.1 It does so by focussing on land holdings and tenures in one village, Kalmandasguri.2 The paper traces these changes by drawing from secondary historical material, oral accounts, and from village-level data gathered in Kalmandasguri in 2005 and 2010. Peasant struggle against oppressive tenures has, of course, a long history in the areas that constitute the present state of West Bengal (Dasgupta 1984, Bakshi 2015). * Research Scholar, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, [email protected] 1 Cooch Behar is spelt in various ways. -

Urban History of Darjeeling Through Phases : a Study of Society, Economy and Polity "The Queen of the Himalayas"

URBAN HISTORY OF DARJEELING THROUGH PHASES : A STUDY OF SOCIETY, ECONOMY AND POLITY OF "THE QUEEN OF THE HIMALAYAS" THESIS SUBMITTED BY SMT. NUPUR DAS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (ARTS) OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL 2007 RESEARCH SUPERVISOR Dr. Dilip Kumar Sarkar Controller of Examinations University of North Bengal CO-SUPERVISOR Professor Pradip Kumar Sengupta Department of Political Science University of North Bengal J<*eP 35^. \A 7)213 UL l.^i87(J7 0 \ OCT 2001 CONTENTS Page No. Preface (i)- (ii) PROLOGUE 01 - 25 Chapter- I : PRE-COLONIAL DARJEELING ... 26 - 48 Chapter- II : COLONIAL URBAN DARJEELING ... 49-106 Chapter-III : POST COLONIAL URBAN SOCIAL DARJEELING ... 107-138 Chapter - IV : POST-COLONIAL URBAN ECONOMIC DARJEELING ... 139-170 Chapter - V : POST-COLONIAL URBAN POLITICAL DARJEELING ... 171-199 Chapter - VI : EPILOGUE 200-218 BIBLIOGRAPHY ,. 219-250 APPENDICES : 251-301 (APPENDIX I to XII) PHOTOGRAPHS PREFACE My interest in the study of political history of Urban Darjeeling developed about two decades ago when I used to accompany my father during his official visits to the different corners of the hills of Darjeeling. Indeed, I have learnt from him my first lesson of history, society, economy, politics and administration of the hill town Darjeeling. My rearing in Darjeeling hills (from Kindergarten to College days) helped me to understand the issues with a difference. My parents provided the every possible congenial space to learn and understand the history of Darjeeling and history of the people of Darjeeling. Soon after my post- graduation from this University, located in the foot-hills of the Darjeeling Himalayas, I was encouraged to take up a study on Darjeeling by my teachers. -

Gorkhaland: Crisis of Statehood' by Romit Bagchi

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 33 Number 1 Article 27 March 2014 Review of 'Gorkhaland: Crisis of Statehood' by Romit Bagchi Roshan P. Rai Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Rai, Roshan P.. 2014. Review of 'Gorkhaland: Crisis of Statehood' by Romit Bagchi. HIMALAYA 33(1). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol33/iss1/27 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Book Reviews Gorkhaland: Crisis of Statehood grasp of the movement. But the major press home his point that the demand focus is on the post-2007 period of the for autonomy is not justified, rather Romit Bagchi. New Delhi; Thousand movement as a means to discuss the than expand his research to question Oaks, California: Sage Publications ‘Crisis of Statehood’, which extremely the existing politically constructed India, 2012. Pp. 447. INR 895 limits the narrative depth of the history. book. (hardback). ISBN 978-81-321-0726-2. Political views vis-à-vis Gorkhaland At the outset, the author lays out are traced from the Communist Reviewed by Roshan P. Rai his opinions that the demand has Party of India’s demand in 1942 for more to it than just statehood, Gorkhasthan, to the demand for Romit Bagchi introduces his book “with more sinister implications” separation from Bengal by the All as “Gorkhaland – A Psychological (p. -

Information of the School

INFORMATION OF THE SCHOOL 1. Name of the School with address : BSF SENIOR SECONDARY RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL (strictly as per Affiliation sanction KADAMTALA (SILIGURI), DISTT. DARJEELING, letter or as permitted by the Board) WEST BENGAL – 734011. with pin code no. (i) E-mail : [email protected] (ii) Ph. No. : 0353-2580820 (iii) Fax No. : 0353-2580820 2. Year of Establishment of School : 8TH SEPTEMBER 1990 3. Whether NOC from State/UT or : Not Applicable recommendation of Embassy of India obtained? 4. Is the School is recognized, if yes : Yes, by Central Board of Secondary Education by which Authority 5. Status of Affiliation Permanent/Regular/Provisional : Provisional (i) Affiliation No. : 2430025 (ii) Affiliation with the Board since : since 01-04-1991 (iii) Extension of Affiliation upto : upto 31-03- 2019 6. Name of Trust/Society/Company : BSF EDUCATION FUND SOCIETY, NEW DELHI Registered under Section 25 of the Company Act, 1956. Period upto which Registration of Trust/Society is valid 7. List of members of School Managing : As per Appendix ‘A1’ Committee with their Address/tenure and post held 8. Name and official address of the : SH. K. N. CHOUBEY,IPS (IG, BSF NB FTR) Manager/ President/ Chairman/ KADAMTALA, PO. KADAMTALA, SILIGURI, Correspondent DISTT. DARJEELING (WEST BENGAL). (i) E-mail : Not Available (ii) Ph. No. : Office : 0353-2580160 (Extn. No. 300) Resident : 0353-2580161 (Extn. No. 301) (iii) Fax No. : Not Available Contd. on page 2 (2) 9. Area of school campus (i) In Acres : 8 acres (Eight) (ii) In Sq. mtrs. : 32374.8512 (iii) Built up area (Sq. mtrs.) : 3196 (iv) Area of playground in Sq. -

A Case Study of the Tea Plantation Industry in Himalayan and Sub - Himalayan Region of Bengal (1879 – 2000)

RISE AND FALL OF THE BENGALI ENTREPRENEURSHIP: A CASE STUDY OF THE TEA PLANTATION INDUSTRY IN HIMALAYAN AND SUB - HIMALAYAN REGION OF BENGAL (1879 – 2000) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY BY SUPAM BISWAS GUIDE Dr. SHYAMAL CH. GUHA ROY CO – GUIDE PROFESSOR ANANDA GOPAL GHOSH DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL 2015 JULY DECLARATION I declare that the thesis entitled RISE AND FALL OF THE BENGALI ENTREPRENEURSHIP: A CASE STUDY OF THE TEA PLANTATION INDUSTRY IN HIMALAYAN AND SUB - HIMALAYAN REGION OF BENGAL (1879 – 2000) has been prepared by me under the guidance of DR. Shyamal Ch. Guha Roy, Retired Associate Professor, Dept. of History, Siliguri College, Dist – Darjeeling and co – guidance of Retired Professor Ananda Gopal Ghosh , Dept. of History, University of North Bengal. No part of this thesis has formed the basis for the award of any degree or fellowship previously. Supam Biswas Department of History North Bengal University, Raja Rammuhanpur, Dist. Darjeeling, West Bengal. Date: 18.06.2015 Abstract Title Rise and Fall of The Bengali Entrepreneurship: A Case Study of The Tea Plantation Industry In Himalayan and Sub Himalayan Region of Bengal (1879 – 2000) The ownership and control of the tea planting and manufacturing companies in the Himalayan and sub – Himalayan region of Bengal were enjoyed by two communities, to wit the Europeans and the Indians especially the Bengalis migrated from various part of undivided Eastern and Southern Bengal. In the true sense the Europeans were the harbinger in this field. Assam by far the foremost region in tea production was closely followed by Bengal whose tea producing areas included the hill areas and the plains of the Terai in Darjeeling district, the Dooars in Jalpaiguri district and Chittagong. -

The Study Area

THE STUDY AREA 2.1 GENERALFEATURES 2.1.1 Location and besic informations ofthe area Darjeeling is a hilly district situated at the northernmost end of the Indian state of West Bengal. It has a hammer or an inverted wedge shaped appearance. Its location in the globe may be detected between latitudes of 26° 27'05" Nand 27° 13 ' 10" Nand longitudes of87° 59' 30" and 88° 53' E (Fig. 2. 1). The southern-most point is located near Bidhan Nagar village ofPhansidewa block the nmthernmost point at trijunction near Phalut; like wise the widest west-east dimension of the di strict lies between Sabarkum 2 near Sandakphu and Todey village along river Jaldhaka. It comprises an area of3, 149 km . Table 2.1. Some basic data for the district of Darjeeling (Source: Administrative Report ofDatjeeling District, 201 1- 12, http://darjeeling.gov.in) Area 3,149 kmL Area of H ill portion 2417.3 knr' T erai (Plains) Portion 731.7 km_L Sub Divisoins 4 [Datjeeling, Kurseong, Kalimpong, Si1iguri] Blocks 12 [Datjeeling-Pulbazar, Rangli-Rangliot, Jorebunglow-Sukiapokhari, Kalimpong - I, Kalimpong - II, Gorubathan, Kurseong, Mirik, Matigara, Naxalbari, Kharibari & Phansidewa] Police Stations 16 [Sadar, Jorebunglow, Pulbazar, Sukiapokhari, Lodhama, Rangli- Rangliot, Mirik, Kurseong, Kalimpong, Gorubathan, Siliguri, Matigara, Bagdogra, Naxalbari, Phansidewa & Kharibari] N o . ofVillages & Corporation - 01 (Siliguri) Towns Municipalities - 04 (Darjeeling, Kurseong, Kalimpong, Mirik) Gram Pancbayats - 134 Total Forest Cover 1,204 kmL (38.23 %) [Source: Sta te of Forest