Eva Merz in Conversation with Paul Anderson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Desert Fever: an Overview of Mining History of the California Desert Conservation Area

Desert Fever: An Overview of Mining History of the California Desert Conservation Area DESERT FEVER: An Overview of Mining in the California Desert Conservation Area Contract No. CA·060·CT7·2776 Prepared For: DESERT PLANNING STAFF BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR 3610 Central Avenue, Suite 402 Riverside, California 92506 Prepared By: Gary L. Shumway Larry Vredenburgh Russell Hartill February, 1980 1 Desert Fever: An Overview of Mining History of the California Desert Conservation Area Copyright © 1980 by Russ Hartill Larry Vredenburgh Gary Shumway 2 Desert Fever: An Overview of Mining History of the California Desert Conservation Area Table of Contents PREFACE .................................................................................................................................................. 7 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 9 IMPERIAL COUNTY................................................................................................................................. 12 CALIFORNIA'S FIRST SPANISH MINERS............................................................................................ 12 CARGO MUCHACHO MINE ............................................................................................................. 13 TUMCO MINE ................................................................................................................................ 13 PASADENA MINE -

Interim Concession Contract Glory Hole Concession Area

New Melones Lake Concession Prospectus Interim Concession Contract Glory Hole Concession Area Interim Concession Contract Glory Hole Concession Area New Melones Lake Part 7.20 – Interim Concessions Contract. Interim Concession Contract 1 New Melones Lake Concession Prospectus Interim Concession Contract Identification of The Parties Identification of The Parties This Interim Concession Contract is made and entered into by and between the United States of America, acting, through the Area Manager, Central California Area Office of the Mid Pacific Region, Bureau of Reclamation (as delegated), hereinafter referred to as “Reclamation” and Shasta Lake Resorts (SLR), a California limited partnership, hereinafter referred to as the “Concession Contractor”; together, Reclamation and the Concession Contractor to be referred to as “the Parties”. Witnesseth: Whereas, the United States has withdrawn and acquired certain lands for the New Melones Unit; Central Valley Project (New Melones Project), on the Stanislaus River, California, and Reclamation is operating the New Melones Project including said lands; and Whereas,, Reclamation has determined that certain New Melones Project facilities and services are necessary and appropriate for the public use and enjoyment, and has designated the Glory Hole Concession Area for this purpose, and the Concession Contractor is willing to provide such services; and Whereas,, the Concession Contractor wishes to utilize a portion of said lands within the Glory Hole Concession Area for the location, construction, -

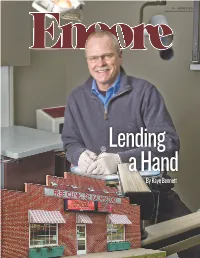

Lending a Hand (Pdf)

tJANUARY 2010 www.encorekalamazoo.com ;T]SX]V P7P]S 1h:PhT1T]]Tcc >d^fk)lmmloqrkfqv+ I^pq vb^o t^p _ob^qeq^hfkd) _rq fqÒp vlro tb^iqe+ Lro `ifbkq*`bkqof` qb^j efpqlov+ Te^q j^qqbop qla^v ^ob qeb ^mmol^`etfiimolsfabvlrtfqe^ibsbi pqbmpvlrq^hbqljlsbclot^oa+Tefib lc^qqbkqflk)abq^fi^kaobpmlkpfsbkbpp qebvb^ofppqfiivlrkd)j^hb^obplir* qe^qÒp sfoqr^iiv rkeb^oa lc fk lro qflk ql `^ii qeb tb^iqe j^k^dbjbkq fkarpqovqebpba^vp+Pljr`epl)fkc^`q) qb^j ^q Dobbkib^c Qorpq+ TbÒii ebim qe^q fk lro jlpq ob`bkq `ifbkq prosbv) vlr k^sfd^qb qeb tloiaÒp fk`ob^pfkdiv lsbo 65" lc obpmlkabkqp p^fa qebvÒa `ljmibu ^ka bkqtfkba j^ohbqp tfqe ob`ljjbkarpqllqebop+Lmmloqrkfqv `i^ofqv ^ka ^ pfkdib jfkaba cl`rp7 fphkl`hfkd)^kaqe^qÒpdlla+@^iirp) qeb mobpbos^qflk ^ka doltqe lc ^katbÒiiebimvlrlmbkqeballo+ Cfk^k`f^iPb`rofqvcoljDbkbo^qflkqlDbkbo^qflk /..plrqeolpbpqobbqh^i^j^wll)jf16--4ttt+dobbkib^cqorpq+`lj/36+055+65--5--+1.3+1222 (+,(,!,"&%".&0%", ,+)*&"'-, !,/+',,!+,!0 &0!*,+,()) (*,-',%0,!(+*(-'&#-&)"',(,"(' **".,*('+(' /!*,(),&(*"+)"%"+,+)-,&0-,-*$"',(&(,"(' !*0+%,* /+-)'(-, %"' ,,*,!'&0(%+% '+0/",!*,"',0&0!*,/+"' ,!*" !,)%,!'++-*+","+,(0 0+('$'(/+,!, ,(( %+($'(/+,!,%% "+', ,,"' )+,& '0(-$'(//!, '",!*"+,!*+,(&0%" *('+('!%,! (& !*, TICKETS ON SALE NOW! FRIDAY–SUNDAY, JAN. 29–31 | TIMES VARY TUESDAY–THURSDAY, FEB. 23–25 @ 7 P.M. Menopause The Musical® is set in a department store, TALE AS OLD AS TIME, TRUE AS IT CAN BE. Disney’s where four women with seemingly nothing in common BEAUTY AND THE BEAST, the smash hit Broadway but a black lace bra meet by chance at a lingerie sale. musical, is coming back to Kalamazoo! Based on the The all-female cast makes fun of their woeful hot flashes, Academy Award-winning animated feature film, this forgetfulness, mood swings, wrinkles, night sweats and eye-popping spectacle has won the hearts of over 35 chocolate binges. -

A Small Town in Germany

A Small Town in Germany by John le Carré, 1931– Published: 1968 J J J J J I I I I I Table of Contents Introduction by Hari Kunzru Prologue The Hunter and the Hunted. & Chapter 1 … Mr Meadowes and Mr Cork. Chapter 2 … „I Could Hear their Screaming on the Telephone…” Chapter 3 … Alan Turner. Chapter 4 … Decembers of Renewal. Chapter 5 … John Gaunt. Chapter 6 … The Memory Man. Chapter 7 … De Lisle. Chapter 8 … Jenny Pargiter. Chapter 9 … Guilty Thursday. Chapter 10 … Kultur at the Bradfields. Chapter 11 … Königswinter. Chapter 12 … „And There was Leo. In the Second Class.” Chapter 13 … The Strain of Being a Pig. Chapter 14 … Thursday’s Child. Chapter 15 … The Glory Hole. Chapter 16 … „It’s All a Fake.” Chapter 17 … Praschko. Epilogue * * * * * All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental. J J J J J I I I I I Introduction (by Hari Kunzru) In 1961, a young German columnist published a scathing article in konkret , a popular left-wing magazine. ‘The attempt to turn twelve years of German history into a taboo subject has failed’, she wrote, in a piece provocatively headlined ‘ Hitler in Euch ’ (‘Hitler Within You’). ‘The narrowing gap between the fronts of history and politics, between the accusers, the accused, and the victims, haunts the younger generation.’ That same year a young British SIS officer, posted under diplomatic cover to the embassy in Bonn, published his first novel. As observers of (and participants in) the danse macabre of German cold war politics, Ulrike Meinhof and John le Carré could hardly have been more different. -

19Th Encounters Short Film and Animation Festival

OUR THANKS TO SUPPORTING PARTNERS Daniel Goodwin, Dan Drake, Jemma Ballantyne, Denne Dempsey, David Allain, Jessica Gormley, Sofia Bak, Maude Laflamme, Marie Morin, Laurent Gagliardi, José Dubeau, Mei Rider, Astrid Bulmer, Agathe Bonitzer, Karel Och, Philip Bloom, Oli Harbottle, Virginie Sélavy, William C. Martell, Nicolangelo Gelormini, Sarah Radclyffe, Gaia Meucci, Karel Spesny, Kate Tancred, Nic Baisely, Ashlin Ritchie, Elliot Scott, David Reynolds, Fuad Omar, Manuel Diaz, Lupita Ayala, Eduardo Gomez, David Martinez, Mariela Velasco, Sean Chavarria, Junko Takekawa, Helena Culliney, Diederik Smet, Claire Maher, Chris France, Jessica Leung, Kate Bradford, Jacques Henry-Bezy, Adam Woodward, Denise Parkinson, Natasha Bishop, Andrew Birnie Lukas G-G, Ruby the Rebel, Janine Gerhardt, Jiri Gerhardt Greco, David Theobald, Steve Mitchell, Robert Lenkiewicz, the ladies from Cinemacity, Novi Sad, Una at Film Centre Serbia, Serbian City CULTURAL PARTNERS Club London, Micha from ORF, Zekic at Divx, Marcus Agar at WildRooster, Soulfood Films, TeleFilm Croatia, Emotion Film/Vertigo Slovenia, Artikulacija Montenegro, Arsmedia, Super-films Belgrade, Manuela at IntraMovies and Latido Films, Tiska Wiederman, Jaimy Warner, Elli Raynai, Facundo Campos, Sabrina Kunert, Marvin Shepherd, Eloisa Suarez, Daniel Kresmery, Reka Kresmery, Maxime Feyers, Francois-Xavier Alet, Philip Gambrill, Michael Barker, Keith Greenhalgh, Dean Goldberg, Patrick Tucker, Col Spector, Jurgen Wolff, Martin Gooch, Simon Hunter, Chris Thomas, Tony Morris, Dave Reynolds, Zara Ballantyne -

Case Study Findings

Case Study no. 3 The provision of residential care for children in Scotland by Quarriers, Aberlour Child Care Trust, and Barnardo’s between 1921 and 1991 Evidential Hearings: 23 October 2018 to 12 February 2019 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.childabuseinquiry.scot Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to [email protected] Published January 2020 Produced by APS Group Scotland, 21 Tennant Street, Edinburgh EH6 5NA Case Study no. 3 The provision of residential care for children in Scotland by Quarriers, Aberlour Child Care Trust, and Barnardo’s between 1921 and 1991 Evidential Hearings: 23 October 2018 to 12 February 2019 Contents Preface v Summary ix 1. Introduction 1 2. Quarriers, Aberlour, and Barnardo’s 3 Quarriers 3 Aberlour 8 Barnardo’s 9 3. General descriptions and regimes 11 Introduction 11 Home 11 Collusion? 12 Overviews of experiences in the care of the three providers 12 An outside view 17 Failures to follow providers’ own rules 17 Abuse: contributory factors 22 Positives 24 4. Physical Abuse 25 Introduction 25 Attitudes to the corporal punishment of children prevalent over the period of this case study 25 Quarriers 29 Aberlour 39 Barnardo’s 43 Responses to evidence of physical abuse 46 Conclusions about physical abuse 46 5. -

T. Coraghessan Boyle Student Papers 5260

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8833vdw No online items FInding aid for the T. Coraghessan Boyle student papers 5260 Sue Luftschein; inventory prepared by Gloria Pugliese USC Libraries Special Collections Doheny Memorial Library 206 3550 Trousdale Parkway Los Angeles, California 90089-0189 213-740-5900 [email protected] FInding aid for the T. 5260 1 Coraghessan Boyle student papers 5260 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: USC Libraries Special Collections Title: T. Coraghessan Boyle student papers creator: Boyle, T. Coraghessan Identifier/Call Number: 5260 Physical Description: 10 Linear Feet10 boxes Date (inclusive): 1978-2012 Abstract: Short stories produced by students in T. Coraghessan Boyle's creative writing classes at USC. Storage Unit: 1, 6, 10 Storage Unit: 2, 5, 8 Storage Unit: 4, 7 Scope and Contents Short stories produced by students in T. Coraghessan Boyle's creative writing classes at USC. Conditions Governing Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE. Advance notice required for access. Conditions Governing Use All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Manuscripts Librarian. Permission for publication is given on behalf of Special Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which must also be obtained. Preferred Citation [Box/folder no. or item name], T. Coraghessan Boyle student papers, Collection no. 5260, University Archives, Special Collections, USC Libraries, University of Southern California Subjects and Indexing Terms Short stories Boyle, T. Coraghessan Boyle, T. Coraghessan -- Archives University of Southern California -- Students Box 8 Abani, Chris. -

U·M·I University Microfilms International a Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, M148106·1346 USA 313/761·4700 800/521·0600

Isotopic and geochemical characteristics of Laramide igneous rocks in Arizona. Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Lang, James Robert. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 20:48:42 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/185600 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. -

Eugene Nelson BREAK THEIR HAUGHTY POWER Joe Murphy In

Eugene Nelson BREAK THEIR HAUGHTY POWER Joe Murphy in the Heyday of the Wobblies A biographical novel Cover oil painting by Liz Penniman They have taken untold millions that they never toiled to earn, but without our brain and muscle not a single wheel could turn; We can break their haughty power, gain our freedom when we learn That the Union makes us strong. Ralph Chaplin: Solidarity Forever Digital edition: C Carretero Spread: Confederación Sindical Solidaridad Obrera http://www.solidaridadobrera.org/ateneo_nacho/biblioteca.html Joe Murphy at age 27, in the spring of 1933 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I. BILL HAYWOOD'S BOY II. A REAL WOBBLY III. FIRST LOVE IV. CENTRALIA V. LAWYER FOR THE DAMNED VI. DISHES ON THE ROOF VII. `WE RE ALL LEADERS´ VIII. THERE'S A BEAUTY ABOUT BOXCARS IX. FLYING SQUADRON X. THE HIGH LONESOME XI. MISSOURI XII. THE GREAT RAILROAD STRIKE XIII. AN OBJECTION TO DESPOTISM XIV. THE LABOR SPY XV. ALREADY IN HELL XVI. THE PORTLAND REVOLUTION XVII. THE DEHORN SQUAD XVIII. TO SEA! XIX. FROM VLADIVOSTOK TO SYDNEY XX. SUCH A LOT OF DEVILS' XXI. AND STILL THE WOBBLIES SANG XXII. `SHORT PAY-SHORT SHOVEL´ XXIII. FLYING HIGH XXIV. HELEN KELLER: ’WHY I BECAME AN IWW´ XXV. `JESUS OF THE LUMBER WORKERS' XXVI. THE GLORY HOLE XXVII. IT WAS MY CAMELOT XXVIII. THE SPLIT XXIX. HOLD THE FORT XXX. KEEP ON TRAMPIN' XXXI. DRIVING WITH DEBS XXXII. A GLIMMER OF HOPE XXXIII. `ON TO COLORADO, WOBBLY REBELS!' XXXIV. THE GIRL IN THE RED DRESS XXXV. A PAIR OF SLIPPERS FOR THE SAINT XXXVI.