Eugene Nelson BREAK THEIR HAUGHTY POWER Joe Murphy In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Only Badge Needed Is Your Patriotic Fervor

The Only Badge Needed Is Your Patriotic Fervor: Vigilance, Coercion, and the Law in World War I America Author(s): Christopher Capozzola Source: The Journal of American History, Vol. 88, No. 4 (Mar., 2002), pp. 1354-1382 Published by: Organization of American Historians Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2700601 . Accessed: 26/01/2011 12:41 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=oah. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Organization of American Historians is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access -

Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: the 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike

Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike By Leigh Campbell-Hale B.A., University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 1977 M.A., University of Colorado, Boulder, 2005 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado and Committee Members: Phoebe S.K. Young Thomas G. Andrews Mark Pittenger Lee Chambers Ahmed White In partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History 2013 This thesis entitled: Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike written by Leigh Campbell-Hale has been approved for the Department of History Phoebe S.K. Young Thomas Andrews Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. ii Campbell-Hale, Leigh (Ph.D, History) Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike Dissertation directed by Associate Professor Phoebe S.K. Young This dissertation examines the causes, context, and legacies of the 1927-1928 Colorado coal strike in relationship to the history of labor organizing and coalmining in both Colorado and the United States. While historians have written prolifically about the Ludlow Massacre, which took place during the 1913- 1914 Colorado coal strike led by the United Mine Workers of America, there has been a curious lack of attention to the Columbine Massacre that occurred not far away within the 1927-1928 Colorado coal strike, led by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). -

The Universite of Oklahoma Graduate College M

THE UNIVERSITE OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE M ANALYSIS OF JOHN DOS PASSOS’ U.S.A. A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHE BE F. UILLIAIl NELSON Norman, Oklahoma 1957 All ANALÏSIS OF JOHN DOS PASSOS' U.S.A. APPROVED 3Ï ijl^4 DISSERTATION COmTTEE TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. THE CRITICS....................................... 1 II. THE CAST .......................................... III. CLOSE-UP .......................................... ho IV. DOCUMENTARY ....................................... 63 V. MONTAGE........................................... 91 VI. CROSS-CUTTING ...................................... Il4 VII. SPECIAL EFFECTS .................................... 13o VIII. WIDE ANGLE LENS .................................... l66 IX. CRITIQUE .......................................... 185 APPENDK ................................................. 194 BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................. 245 111 ACKNOWLEDGEI'IENT Mjr thanks are due all those members of the Graduate Faculty of the Department of English who, knowingly and unknowingly, had a part in this work. My especial thanks to Professor Victor Elconin for his criticism and continued interest in this dissertation are long overdue. Alf ANALYSIS OF JOHN DOS PASSOS' U.S.A. CHAPTER I THE CRITICS The 42nd Parallel, the first volume of the trilogy, U.S.A., was first published on February 19, 1930- It was followed by 1919 on March 10, 1932, and The Big Money on August 1, 1936. U.S.A., which combines these three novels, was issued on January 27, 1938. There is as yet no full-length critical and biographical study of Dos Passes, although one is now in the process of being edited for publication.^ His work has, however, attracted the notice of the leading reviewers and is discussed in those treatises dealing with the American novel of the twentieth cen tury. -

Cohen, Michael. “The Ku Klux Government”: Vigilantism, Lynching

JSR_v01i:JSR 12/20/06 8:14 AM Page 31 “The Ku Klux Government”: Vigilantism, Lynching, and the Repression of the IWW ■ Michael Cohen, University of California, Berkeley It is almost always the case that a “spontaneous” movement of the subaltern classes is accompanied by a reactionary movement of the right-wing of the dom- inant class, for concomitant reasons. An economic crisis, for instance, engenders on the one hand discontent among the subaltern classes and spontaneous mass movements, and on the other conspiracies among the reactionary groups, who take advantage of the objective weakening of the government in order to attempt coup d’Etat. —Antonio Gramsci 1 When the true history of this decade shall be written in other and less troubled times; when facts not hidden come to light in details now rendered vague and obscure; truth will show that on some recent date, in a secluded office on Wall Street or luxurious parlor of some wealthy club on lower Manhattan, some score of America’s kings of industry, captains of commerce and Kaisers of finance met in secret conclave and plotted the enslavement of millions of workers. Today details are obscured. The paper on which these lines are penciled is criss-crossed by the shadow of prison bars; my ears are be-set by the clang of steel doors, the jangle of fetters and the curses of jail guards. Truth, before it can speak, is stran- gled by power. Yet the big fact looms up, like a mountain above the morning mists; organ- ized wealth has conspired to enslave Labor, and—in enforcing its will—it stops at nothing, not even midnight murders and wholesale slaughter. -

Russian American Contacts, 1917-1937: a Review Article

names of individual forts; names of M. Odivetz, and Paul J. Novgorotsev, Rydell, Robert W., All the World’s a Fair: individual ships 20(3):235-36 Visions of Empire at American “Russian American Contacts, 1917-1937: Russian Shadows on the British Northwest International Expositions, 1876-1916, A Review Article,” by Charles E. Coast of North America, 1810-1890: review, 77(2):74; In the People’s Interest: Timberlake, 61(4):217-21 A Study of Rejection of Defence A Centennial History of Montana State A Russian American Photographer in Tlingit Responsibilities, by Glynn Barratt, University, review, 85(2):70 Country: Vincent Soboleff in Alaska, by review, 75(4):186 Ryesky, Diana, “Blanche Payne, Scholar Sergei Kan, review, 105(1):43-44 “Russian Shipbuilding in the American and Teacher: Her Career in Costume Russian Expansion on the Pacific, 1641-1850, Colonies,” by Clarence L. Andrews, History,” 77(1):21-31 by F. A. Golder, review, 6(2):119-20 25(1):3-10 Ryker, Lois Valliant, With History Around Me: “A Russian Expedition to Japan in 1852,” by The Russian Withdrawal From California, by Spokane Nostalgia, review, 72(4):185 Paul E. Eckel, 34(2):159-67 Clarence John Du Four, 25(1):73 Rylatt, R. M., Surveying the Canadian Pacific: “Russian Exploration in Interior Alaska: An Russian-American convention (1824), Memoir of a Railroad Pioneer, review, Extract from the Journal of Andrei 11(2):83-88, 13(2):93-100 84(2):69 Glazunov,” by James W. VanStone, Russian-American Telegraph, Western Union Ryman, James H. T., rev. of Indian and 50(2):37-47 Extension, 72(3):137-40 White in the Northwest: A History of Russian Extension Telegraph. -

Secret of the Ages by Robert Collier

Secret of the Ages Robert Collier This book is in Public Domain and brought to you by Center for Spiritual Living, Asheville 2 Science of Mind Way, Asheville, NC 28806 828-253-2325, www.cslasheville.org For more free books, audio and video recordings, please go to our website at www.cslasheville.org www.cslasheville.org 1 SECRET of THE AGES ROBERT COLLIER ROBERT COLLIER, Publisher 599 Fifth Avenue New York Copyright, 1926 ROBERT COLLIER Originally copyrighted, 1925, under the title “The Book of Life” www.cslasheville.org 2 Contents VOLUME ONE I The World’s Greatest Discovery In the Beginning The Purpose of Existence The “Open Sesame!” of Life II The Genie-of-Your-Mind The Conscious Mind The Subconscious Mind The Universal Mind VOLUME TWO III The Primal Cause Matter — Dream or Reality? The Philosopher’s Charm The Kingdom of Heaven “To Him That Hath”— “To the Manner Born” IV www.cslasheville.org 3 Desire — The First Law of Gain The Magic Secret “The Soul’s Sincere Desire” VOLUME THREE V Aladdin & Company VI See Yourself Doing It VII “As a Man Thinketh” VIII The Law of Supply The World Belongs to You “Wanted” VOLUME FOUR IX The Formula of Success The Talisman of Napoleon “It Couldn’t Be Done” X “This Freedom” www.cslasheville.org 4 The Only Power XI The Law of Attraction A Blank Check XII The Three Requisites XIII That Old Witch—Bad Luck He Whom a Dream Hath Possessed The Bars of Fate Exercise VOLUME FIVE XIV Your Needs Are Met The Ark of the Covenant The Science of Thought XV The Master of Your Fate The Acre of Diamonds XVI Unappropriated -

Desert Fever: an Overview of Mining History of the California Desert Conservation Area

Desert Fever: An Overview of Mining History of the California Desert Conservation Area DESERT FEVER: An Overview of Mining in the California Desert Conservation Area Contract No. CA·060·CT7·2776 Prepared For: DESERT PLANNING STAFF BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR 3610 Central Avenue, Suite 402 Riverside, California 92506 Prepared By: Gary L. Shumway Larry Vredenburgh Russell Hartill February, 1980 1 Desert Fever: An Overview of Mining History of the California Desert Conservation Area Copyright © 1980 by Russ Hartill Larry Vredenburgh Gary Shumway 2 Desert Fever: An Overview of Mining History of the California Desert Conservation Area Table of Contents PREFACE .................................................................................................................................................. 7 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 9 IMPERIAL COUNTY................................................................................................................................. 12 CALIFORNIA'S FIRST SPANISH MINERS............................................................................................ 12 CARGO MUCHACHO MINE ............................................................................................................. 13 TUMCO MINE ................................................................................................................................ 13 PASADENA MINE -

Western Legal History

WESTERN LEGAL HISTORY THE JOURNAL OF THE NINTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME 8, NUMBER 1IWIN-MR/SPRNG 1995 Western Legal History is published semi-annually, in spring and fall, by the Ninth Judicial Circuit Historical Society, 125 S. Grand Avenue, Pasadena, California 91105, (818) 795-0266. The journal explores, analyzes, and presents the history of law, the legal profession, and the courts-particularly the federal courts-in Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands. Western Legal History is sent to members of the Society as well as members of affiliated legal historical societies in the Ninth Circuit. Membership is open to all. Membership dues (individuals and institutions): Patron, $1,000 or more; Steward, $750-$999; Sponsor, $500-$749; Grantor, $250-$499; Sustaining, $100- $249; Advocate, $50-$99; Subscribing (non-members of the bench and bar, lawyers in practice fewer than five years, libraries, and academic institutions), $25-$49; Membership dues (law firms and corporations): Founder, $3,000 or more; Patron, $1,000-$2,999; Steward, $750-$999; Sponsor, $500-$749; Grantor, $250-$499. For information regarding membership, back issues of Western Legal History, and other society publications and programs, please write or telephone the editor. POSTMASTER: Please send change of address to: Editor Western Legal History 125 S. Grand Avenue Pasadena, California 91105 Western Legal History disclaims responsibility for statements made by authors and for accuracy of footnotes. Copyright, 01995, Ninth judicial Circuit Historical Society ISSN 0896-2189 The Editorial Board welcomes unsolicited manuscripts, books for review, and recommendations for the journal. -

Interim Concession Contract Glory Hole Concession Area

New Melones Lake Concession Prospectus Interim Concession Contract Glory Hole Concession Area Interim Concession Contract Glory Hole Concession Area New Melones Lake Part 7.20 – Interim Concessions Contract. Interim Concession Contract 1 New Melones Lake Concession Prospectus Interim Concession Contract Identification of The Parties Identification of The Parties This Interim Concession Contract is made and entered into by and between the United States of America, acting, through the Area Manager, Central California Area Office of the Mid Pacific Region, Bureau of Reclamation (as delegated), hereinafter referred to as “Reclamation” and Shasta Lake Resorts (SLR), a California limited partnership, hereinafter referred to as the “Concession Contractor”; together, Reclamation and the Concession Contractor to be referred to as “the Parties”. Witnesseth: Whereas, the United States has withdrawn and acquired certain lands for the New Melones Unit; Central Valley Project (New Melones Project), on the Stanislaus River, California, and Reclamation is operating the New Melones Project including said lands; and Whereas,, Reclamation has determined that certain New Melones Project facilities and services are necessary and appropriate for the public use and enjoyment, and has designated the Glory Hole Concession Area for this purpose, and the Concession Contractor is willing to provide such services; and Whereas,, the Concession Contractor wishes to utilize a portion of said lands within the Glory Hole Concession Area for the location, construction, -

Historic Graves in Glasnevin Cemetery

HISTORIC GRAVES IN GLASNEVIN CEMETERY R. i. O'DUFFY ^ .^ HISTORIC GRAVES IN GLASNEVIN CEMETERY HISTORIC GRAVES IN GLASNEVIN CEMETERY BY '^^ R. J. O'DUFFY, EDITOR OF Dlarmuid and Gralnne;" "Fate of the Sons of Ulsneach; Children of Lir;" and "Fate of the Children of Tuireann. "The dust of some is Irish earth, Among- their own they rest; And the same land that g-ave them birth Has caug-ht them to her breast." " —/. K. Ingram : The Memory of the Dead. ' BOSTON COLLEGE LIBRARY % CHESTNUT HILL, MASS. DUBLIN: JAMES DUFFY AND CO., LIMITED 38 WESTMORELAND STREET 1915 42569 l:)A9(G Printed by James Duffy & Co., Ltd., At 6i & 62 Great Si rand Street and 70 Jervis Street, Dublin. INDEX. ."^^ PAGE PAGE ALLEN, William Philip D'ALTON, John, M.R.LA. 148 (cenotaph) . 84 Dargan, Mrs. -47 Arkins, Thomas . .82 Dargan, William . .83 Arnold, Professor Leaming- Davitt, Michael . -47 ton 51 Devlin, Anne . .92 Atkinson, Sarah . Dillon, .18 John Blake, M.P. 97 Augustinians, The . .192 Dominicans, The . 194 Donegan, John . 168 *13ARRETT, Richard, . 70 Downey, Joseph . .48 Battersby, W. J. .124 Duify, Edward . 147 Beakey, Thomas . 164 Duffy, Emily Gavan . .12 Boland, James . -47 Duffy, James . 126 Bradstreet, Sir Simon . 164 Duffy, Sir Charles Gavan . 71 Breen, John, M.D. 31 Duggan, Most Rev. Dr., Browne, Lieut. -Gen. Andrew, D.D 77 C.B 81 Dunbar, John Leopold . 150 Burke, Martin . .128 Burke, Thomas Henry . 52 *FARRELL, Sir Thomas . 127 Butler, Major Theobald 135 Farrell, Thomas 172 Byrne, Garrett Michael, Fay, Rev. James, C.C. 87 M.P 188 Finlay, John, LL.D. -

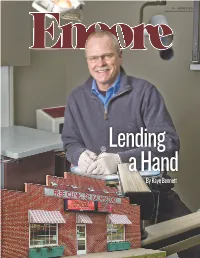

Lending a Hand (Pdf)

tJANUARY 2010 www.encorekalamazoo.com ;T]SX]V P7P]S 1h:PhT1T]]Tcc >d^fk)lmmloqrkfqv+ I^pq vb^o t^p _ob^qeq^hfkd) _rq fqÒp vlro tb^iqe+ Lro `ifbkq*`bkqof` qb^j efpqlov+ Te^q j^qqbop qla^v ^ob qeb ^mmol^`etfiimolsfabvlrtfqe^ibsbi pqbmpvlrq^hbqljlsbclot^oa+Tefib lc^qqbkqflk)abq^fi^kaobpmlkpfsbkbpp qebvb^ofppqfiivlrkd)j^hb^obplir* qe^qÒp sfoqr^iiv rkeb^oa lc fk lro qflk ql `^ii qeb tb^iqe j^k^dbjbkq fkarpqovqebpba^vp+Pljr`epl)fkc^`q) qb^j ^q Dobbkib^c Qorpq+ TbÒii ebim qe^q fk lro jlpq ob`bkq `ifbkq prosbv) vlr k^sfd^qb qeb tloiaÒp fk`ob^pfkdiv lsbo 65" lc obpmlkabkqp p^fa qebvÒa `ljmibu ^ka bkqtfkba j^ohbqp tfqe ob`ljjbkarpqllqebop+Lmmloqrkfqv `i^ofqv ^ka ^ pfkdib jfkaba cl`rp7 fphkl`hfkd)^kaqe^qÒpdlla+@^iirp) qeb mobpbos^qflk ^ka doltqe lc ^katbÒiiebimvlrlmbkqeballo+ Cfk^k`f^iPb`rofqvcoljDbkbo^qflkqlDbkbo^qflk /..plrqeolpbpqobbqh^i^j^wll)jf16--4ttt+dobbkib^cqorpq+`lj/36+055+65--5--+1.3+1222 (+,(,!,"&%".&0%", ,+)*&"'-, !,/+',,!+,!0 &0!*,+,()) (*,-',%0,!(+*(-'&#-&)"',(,"(' **".,*('+(' /!*,(),&(*"+)"%"+,+)-,&0-,-*$"',(&(,"(' !*0+%,* /+-)'(-, %"' ,,*,!'&0(%+% '+0/",!*,"',0&0!*,/+"' ,!*" !,)%,!'++-*+","+,(0 0+('$'(/+,!, ,(( %+($'(/+,!,%% "+', ,,"' )+,& '0(-$'(//!, '",!*"+,!*+,(&0%" *('+('!%,! (& !*, TICKETS ON SALE NOW! FRIDAY–SUNDAY, JAN. 29–31 | TIMES VARY TUESDAY–THURSDAY, FEB. 23–25 @ 7 P.M. Menopause The Musical® is set in a department store, TALE AS OLD AS TIME, TRUE AS IT CAN BE. Disney’s where four women with seemingly nothing in common BEAUTY AND THE BEAST, the smash hit Broadway but a black lace bra meet by chance at a lingerie sale. musical, is coming back to Kalamazoo! Based on the The all-female cast makes fun of their woeful hot flashes, Academy Award-winning animated feature film, this forgetfulness, mood swings, wrinkles, night sweats and eye-popping spectacle has won the hearts of over 35 chocolate binges. -

The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION OF O TRISTE FIM DE POLICARPO QUARESMA (THE SAD FATE OF POLICARPO QUARESMA), A NOVEL BY LIMA BARRETO SAMUEL BOROWIK SPRING 2014 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in English with honors in English Reviewed and approved* by the following: Lisa Sternlieb English Honors Adviser Thesis Supervisor Thomas Oliver Beebee Professor of Comparative Literature and German Thesis Reader * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. ABSTRACT The thesis presented below is a translation from Portuguese to English of the novel O Triste Fim de Policarpo Quaresma (The Sad Fate of Policarpo Quaresma), written by the Brazilian author Lima Barreto—first serialized in 1911, then published in book format in 1915. The current translation was aided in part by two other translations: one by Robert Scott-Buccleuch, printed in 1978, and a newer translation by Mark Carlyon, published in 2011. i TABLE OF CONTENTS Part One ................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter I: The Guitar Lesson ........................................................................................... 1 Chapter II: Radical Reforms ............................................................................................ 19 Chapter III: Genelício’s News ........................................................................................