Of Squares and Uncouth Twenty-Eight-Sided Figures: Reflections on Gomilion and Lighfoot After Half a Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Made Nonviolent Protest Effective During the Civil Rights Movement?

NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 5011th Grade Civil Rights Inquiry What Made Nonviolent Protest Effective during the Civil Rights Movement? © Bettmann / © Corbis/AP Images. Supporting Questions 1. What was tHe impact of the Greensboro sit-in protest? 2. What made tHe Montgomery Bus Boycott, BirmingHam campaign, and Selma to Montgomery marcHes effective? 3. How did others use nonviolence effectively during the civil rights movement? THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION- NONCOMMERCIAL- SHAREALIKE 4.0 INTERNATIONAL LICENSE. 1 NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 11th Grade Civil Rights Inquiry What Made Nonviolent Protest Effective during the Civil Rights Movement? 11.10 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CHANGE/DOMESTIC ISSUES (1945 – PRESENT): Racial, gender, and New York State socioeconomic inequalities were addressed By individuals, groups, and organizations. Varying political Social Studies philosophies prompted debates over the role of federal government in regulating the economy and providing Framework Key a social safety net. Idea & Practices Gathering, Using, and Interpreting Evidence Chronological Reasoning and Causation Staging the Discuss tHe recent die-in protests and tHe extent to wHicH tHey are an effective form of nonviolent direct- Question action protest. Supporting Question 1 Supporting Question 2 Supporting Question 3 Guided Student Research Independent Student Research What was tHe impact of tHe What made tHe Montgomery Bus How did otHers use nonviolence GreensBoro sit-in protest? boycott, the Birmingham campaign, effectively during tHe civil rights and tHe Selma to Montgomery movement? marcHes effective? Formative Formative Formative Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Create a cause-and-effect diagram tHat Detail tHe impacts of a range of actors Research the impact of a range of demonstrates the impact of the sit-in and tHe actions tHey took to make tHe actors and tHe effective nonviolent protest by the Greensboro Four. -

IN HONOR of FRED GRAY: MAKING CIVIL RIGHTS LAW from ROSA PARKS to the TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY - Introduction

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 67 Issue 4 Article 10 2017 SYMPOSIUM: IN HONOR OF FRED GRAY: MAKING CIVIL RIGHTS LAW FROM ROSA PARKS TO THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY - Introduction Jonathan L. Entin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jonathan L. Entin, SYMPOSIUM: IN HONOR OF FRED GRAY: MAKING CIVIL RIGHTS LAW FROM ROSA PARKS TO THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY - Introduction, 67 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 1025 (2017) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol67/iss4/10 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 67·Issue 4·2017 —Symposium— In Honor of Fred Gray: Making Civil Rights Law from Rosa Parks to the Twenty-First Century Introduction Jonathan L. Entin† Contents I. Background................................................................................ 1026 II. Supreme Court Cases ............................................................... 1027 A. The Montgomery Bus Boycott: Gayle v. Browder .......................... 1027 B. Freedom of Association: NAACP v. Alabama ex rel. Patterson ....... 1028 C. Racial Gerrymandering: Gomillion v. Lightfoot ............................. 1029 D. Constitutionalizing the Law of -

<Billno> <Sponsor>

<BillNo> <Sponsor> HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION 8020 of the Second Extraordinary Session By Clemmons A RESOLUTION to honor the memory of United States Congressman John Robert Lewis. WHEREAS, the members of this General Assembly were greatly saddened to learn of the passing of United States Congressman John Robert Lewis; and WHEREAS, Congressman John Lewis dedicated his life to protecting human rights, securing civil liberties, and building what he called "The Beloved Community" in America; and WHEREAS, referred to as "one of the most courageous persons the Civil Rights Movement ever produced," Congressman Lewis evidenced dedication and commitment to the highest ethical standards and moral principles and earned the respect of his colleagues on both sides of the aisle in the United States Congress; and WHEREAS, John Lewis, the son of sharecropper parents Eddie and Willie Mae Carter Lewis, was born on February 21, 1940, outside of Troy, Alabama, and was raised on his family's farm with nine siblings; and WHEREAS, he attended segregated public schools in Pike County, Alabama, and, in 1957, became the first member of his family to complete high school; he was vexed by the unfairness of racial segregation and disappointed that the Supreme Court's 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education did not affect his and his classmates' experience in public school; and WHEREAS, Congressman Lewis was inspired to work toward the change he wanted to see by Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s sermons and the outcome of the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955 and -

An Established Leader in Legal Education Robert R

An Established Leader In Legal Education Robert R. Bond, First Graduate, Class of 1943 “Although N. C. Central University School of Law has had to struggle through some difficult periods in its seventy-year history, the School of Law has emerged as a significant contributor to legal education and the legal profession in North Carolina.” Sarah Parker Chief Justice North Carolina State Supreme Court “Central’s success is a tribute to its dedicated faculty and to its graduates who have become influential practitioners, successful politicians and respected members of the judiciary in North Carolina.” Irvin W. Hankins III Past President North Carolina State Bar The NCCU School of Law would like to thank Michael Williford ‘83 and Harry C. Brown Sr. ‘76 for making this publication possible. - Joyvan Malbon '09 - Professor James P. Beckwith, Jr. North Carolina Central University SCHOOL OF LAW OUR MISSION The mission of the North Carolina Central University School of Law is to provide a challenging and broad-based educational program designed to stimulate intellectual inquiry of the highest order, and to foster in each student a deep sense of professional responsibility and personal integrity so as to produce competent and socially responsible members of the legal profession. 2 NCCU SCHOOL OF LAW: SO FAR th 70 Anniversary TABLE OF CONTENTS 70TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION 4 PORTRAITS OF THE DEANS 2009 NORTH CAROLINA CENTRAL UNIVERSITY 6 ROBERT BOND ‘43: The Genesis of North Carolina SCHOOL OF LAW Central University’s School of Law DEAN: 8 THE STARTING POINT RAYMOND C. PIERCE EDITOR: 12 THE EARLY YEARS MARCIA R. -

February 6, 2016 Hawaii Filipino Chronicle 1

FeBruary 6, 2016 HawaII FIlIPIno CHronICle 1 ♦ FEBRUARY 6, 2016 ♦ Photo credit: Jason Moore BIG ISLAND MEMORIES LEGAL NOTES NON-FIcTION STORy sakada day In keeau ImmIgratIon raIds Cause love and sInulog FestIval Fear among ImmIgrant knows no In kona CommunItIes Bounds PRESORTED HAWAII FILIPINO cHRONIcLE STANDARD 94-356 WAIPAHU DEPOT RD., 2ND FLR. U.S. POSTAGE WAIPAHU, HI 96797 PAID HONOLULU, HI PERMIT NO. 9661 2 HawaII FIlIPIno CHronICle FeBruary 6, 2016 EDITORIALS FROM THE PUBLISHER Publisher & Executive Editor ung Hee Fat Choy! Just when Charlie Y. Sonido, M.D. More Filipinos Artists the newness and excitement of Publisher & Managing Editor 2016 has faded, there’s Chinese Chona A. Montesines-Sonido Making News New Year to celebrate. So in the Associate Editors Dennis Galolo | Edwin Quinabo ilipinos are headliners in sports, entertainment, spirit of Chinese New Year, K Contributing Editor beauty pageants and politics to name just a few. One which is officially observed on Belinda Aquino, Ph.D. field that tends to be overlooked is fine arts—and February 8, the Chronicle’s staff and edi- Creative Designer understandably so. Art is often an afterthought and torial board would like to wish our readers Junggoi Peralta a luxury in a Third World Country like the Philip- F a very happy, safe and prosperous Year of the Monkey. Photography pines where the majority of the people work extra For this issue’s cover story, contributing writer Carolyn Tim Llena hard to make ends meet. But with the recent successes of a grow- Administrative Assistant Weygan-Hildebrand introduces us to talented Filipino artist Shalimar Pagulayan ing number of Filipino artists, the international art world is notic- Philip Sabado whose paintings have delighted those fortunate columnists ing that pinoys are pretty damn good when it comes to visually enough to see them up-close-and-personal. -

728 of That Tree That Charles Described, and the Leaves, Exactly What to Do

728 of that tree that Charles described, and the leaves, exactly what to do. Chairman SPECTER. Thank you very much, Senator Feinstein. Senator FEINSTEIN. Thank you very much, Mr. Chairman. Chairman SPECTER. We are going to adjourn for a— Senator COBURN. Senator Specter, I will defer my questions so that we will not have to have the panel come back, if that would be OK, and I will submit some questions. Chairman SPECTER. You are entitled to your round. Senator COBURN. But I think in all courtesy to our distinguished panel, this would release them, and I will be happy to submit some questions for the record. Chairman SPECTER. All right. We will proceed in that manner at your suggestion. As I had said earlier, New York Times reporter, David Rosen- baum, a memorial service is being held for him. he was brutally murdered on the streets of Washington very recently. We will re- cess for just a few moments. I would like the next panel to be ready and the Senators to be ready. [Recess at 10:05 a.m. to 10:40 a.m.] Chairman SPECTER. The hearing will resume. The first witness on our next panel, Panel 5, is Mr. Fred Gray, senior partner at Gray, Langford, Sapp, McGowan, Gray & Nathanson, a veteran civil rights attorney with an extraordinary record of representation. At the age of 24, he represented Ms. Rosa Parks, whose involvement in the historic refusal to give up her seat on the bus to a white man is so well known. That action initiated the Montgomery bus boycott. -

IN SULLIVAN's SHADOW: the USE and ABUSE of LIBEL LAW DURING the CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT a Dissertation Presented to the Facult

IN SULLIVAN’S SHADOW: THE USE AND ABUSE OF LIBEL LAW DURING THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by AIMEE EDMONDSON Dr. Earnest L. Perry Jr., Dissertation Supervisor DECEMBER 2008 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled: IN SULLIVAN’S SHADOW: THE USE AND ABUSE OF LIBEL LAW DURING THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT presented by Aimee Edmondson, a candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. ________________________________ Associate Professor Earnest L. Perry Jr. ________________________________ Professor Richard C. Reuben ________________________________ Associate Professor Carol Anderson ________________________________ Associate Professor Charles N. Davis ________________________________ Assistant Professor Yong Volz In loving memory of my father, Ned Edmondson ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It would be impossible to thank everyone responsible for this work, but special thanks should go to Dr. Earnest L. Perry, Jr., who introduced me to a new world and helped me explore it. I could not have asked for a better mentor. I also must acknowledge Dr. Carol Anderson, whose enthusiasm for the work encouraged and inspired me. Her humor and insight made the journey much more fun and meaningful. Thanks also should be extended to Dr. Charles N. Davis, who helped guide me through my graduate program and make this work what it is. To Professor Richard C. Reuben, special thanks for adding tremendous wisdom to the project. Also, much appreciation to Dr. -

The Birmingham Sixteenth Street Baptist Church Bombing and the Legacy of Judge Frank Minis Johnson Jr

Alabama Law Scholarly Commons Essays, Reviews, and Shorter Works Faculty Scholarship 2019 Justice Delayed, Justice Delivered: The Birmingham Sixteenth Street Baptist Church Bombing and the Legacy of Judge Frank Minis Johnson Jr. Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr. Centennial Symposium & Law Clerks Reunion Kenneth M. Rosen University of Alabama - School of Law, [email protected] W. Keith Watkins William J. Baxley George L. Beck Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.ua.edu/fac_essays Recommended Citation Kenneth M. Rosen, W. K. Watkins, William J. Baxley & George L. Beck, Justice Delayed, Justice Delivered: The Birmingham Sixteenth Street Baptist Church Bombing and the Legacy of Judge Frank Minis Johnson Jr. Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr. Centennial Symposium & Law Clerks Reunion, 71 Ala. L. Rev. 601 (2019). Available at: https://scholarship.law.ua.edu/fac_essays/206 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Alabama Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Essays, Reviews, and Shorter Works by an authorized administrator of Alabama Law Scholarly Commons. JUSTICE DELAYED, JUSTICE DELIVERED: THE BIRMINGHAM SIXTEENTH STREET BAPTIST CHURCH BOMBING AND THE LEGACY OF JUDGE FRANK MINIS JOHNSON JR. Kenneth M. Rosen* & Hon. W Keith Watkins** That delayed justice should be avoided in the United States legal system is fundamentally consistent with American aspirations of doing what is morally right. Answering criticism by other clergy of his civil rights activities, in his famed Letterfrom a BirminghamJail, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. referenced a jurist in proclaiming that "justice too long delayed is justice denied."1 The need for urgency in remedying injustice is clear. -

SYMPOSIUM: in HONOR of FRED GRAY: MAKING CIVIL RIGHTS LAW from ROSA PARKS to the TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY - Introduction Jonathan L

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 67 | Issue 4 2017 SYMPOSIUM: IN HONOR OF FRED GRAY: MAKING CIVIL RIGHTS LAW FROM ROSA PARKS TO THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY - Introduction Jonathan L. Entin Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jonathan L. Entin, SYMPOSIUM: IN HONOR OF FRED GRAY: MAKING CIVIL RIGHTS LAW FROM ROSA PARKS TO THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY - Introduction, 67 Case W. Res. L. Rev. 1025 (2017) Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol67/iss4/10 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 67·Issue 4·2017 —Symposium— In Honor of Fred Gray: Making Civil Rights Law from Rosa Parks to the Twenty-First Century Introduction Jonathan L. Entin† Contents I. Background................................................................................ 1026 II. Supreme Court Cases ............................................................... 1027 A. The Montgomery Bus Boycott: Gayle v. Browder .......................... 1027 B. Freedom of Association: NAACP v. Alabama ex rel. Patterson ....... 1028 C. Racial Gerrymandering: Gomillion v. Lightfoot ............................. 1029 D. Constitutionalizing the Law of Defamation: -

BLACK HISTORY NAME FIND “ATTENTION: EARN MONEY TYPING at HOME! 32,000/Yr Income Potential

.y PAGE 16 The News Argus February 1990 QAJOHNJOHNSONBOWPNXJW MPEMARVACOLLI NSAWLKAE AHSAFB EDN XONSUO EMCNB R SRRE LAJCWC LRS.BCBEB TL ECEN TUDZVRR BEV DAJTO I L JUDJ ZSPBROA TOZ UDPBO Is your fraternity, N A5GA PXTABDA LKZ BBBAK sorority or club interested in earning $1,000.00= for a one- L PCGRM JEHE NBMALC OMXLE week, on-campus marketing project? You must be well- U R K A A MLS C W E D E G X B L R organized and hard working. ■> Call Jenny or Myra at (800) T A SRYN AOLLO XZ YZ S ELAT 592-2121 H NOVPH NANDREWYOU N GMRW Wanted!!! Students to join the E DNE5 0 JOURNE RTRU T HFDA 1990 Student Travel Serv ices’ Sales Team. Earn Cash R OXYV 0 NNEKEN NEDY P QNRS and/or FREE Spring Break travel marketing Spring K l'pqn k jam ESF ARMER OBKH Break packages to Jamaica, Cancun, Acapulco, and P M J S W I L L AMCOSBYRC Daytona Beach. For more information call 1-800-648- N H A R R ETTUBM ANM NC ADEN 4849 G DO RO T HYH EIG HTA FP QDVG Instructors needed to teach cheerleading, dance, JBMEDGAREVERSI PAC GYTT gymnastics at summer camp sites. Interviews scheduled RHARVEYGANTTLUSXD N RMO for February 3rd in Greens boro. To schedule an inter WALTE RWHI TEUFOTWO PXON view: CALL 1-800- 33CHEER OR WRITE: Nation-Wide Cheerleaders, c * X PEO D I CNM KJD I AN EN ASHF 2275 Canterbury Offices, Indiana, PA 15701. BLACK HISTORY NAME FIND “ATTENTION: EARN MONEY TYPING AT HOME! 32,000/yr income potential. -

Bus Ride to Justice to There Could Be a Test Case to Challenge Segregation Laws

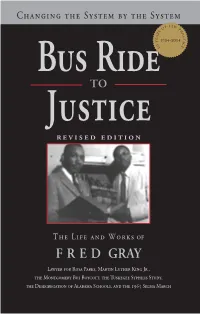

Biography/History/Civil Rights $25.95 FRED Changing the System by the System f law o p r s a irst published in 1995, this best-selling autobiography by acclaimed civil rights r c GRAY a t e attorney Fred D. Gray appears now in a newly revised edition that updates Gray’s i y 1954–2014 c F e 0 remarkable career of “destroying everything segregated that I could find.” Of particular 6 interest will be the details Gray reveals for the first time about Rosa Parks’s 1955 arrest. Gray was the young lawyer for Parks and also Martin Luther King Jr. and the Montgomery Improvement Association, which organized the 382-day Montgomery Bus Boycott after Parks’s arrest. As the last survivor of that inner circle, Gray speaks about the strategic reasons Parks was presented as a demure, random victim of Jim Crow policies when Bus Ride in reality she was a committed, strong-willed activist who was willing to be arrested so Bus Ride to Justice TO there could be a test case to challenge segregation laws. Gray’s remarkable career also includes landmark civil rights cases in voting rights, education, housing, employment, law enforcement, jury selection, and more. He is widely considered one of the most successful civil rights attorneys of the twentieth century and his cases are studied in law schools around the world. In addition he was an ordained Church of Christ minister and was one of the first blacks elected to the Alabama legislature in the modern era. Initially denied entrance to Alabama’s segregated Justice law school, he became the first black president of the Alabama bar association. -

The Least Publicized Aspects of the Montgomery Alabama Bus Boycott

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2016 The Anatomy of a Social Movement: The Least Publicized Aspects of the Montgomery Alabama Bus Boycott Timothy Shands CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/618 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Anatomy of a Social Movement: The Least Publicized Aspects of the Montgomery Alabama Bus Boycott BY Timothy Shands Sociology Department The City College of the City University of New York Mentor Gabriel Haslip-Viera, Ph.D Sociology Department The City College of the City University of New York Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate Division of the Sociology Department of the City College Of the City University of New York in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Spring 2016 Introduction Though some would deny its existence, in the middle of the twentieth century there was firmly in place in the Southern parts of the United States, Alabama in particular, a pervasive system of racial caste. It was an omnipresent system, all too familiar to those at or near the bottom of its hierarchal scale. Clearly in the South, at its foundation was a deleterious obsession with black submissiveness based on nostalgia for the antebellum South. In addition to being symptomatic of a stifling tradition of bigotry and social injustice throughout the South, it was a caste system intent on keeping Black citizens throughout the nation in a “social, political, and economic cellar” (Williams and Greenhaw 125).