An Established Leader in Legal Education Robert R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Made Nonviolent Protest Effective During the Civil Rights Movement?

NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 5011th Grade Civil Rights Inquiry What Made Nonviolent Protest Effective during the Civil Rights Movement? © Bettmann / © Corbis/AP Images. Supporting Questions 1. What was tHe impact of the Greensboro sit-in protest? 2. What made tHe Montgomery Bus Boycott, BirmingHam campaign, and Selma to Montgomery marcHes effective? 3. How did others use nonviolence effectively during the civil rights movement? THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION- NONCOMMERCIAL- SHAREALIKE 4.0 INTERNATIONAL LICENSE. 1 NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 11th Grade Civil Rights Inquiry What Made Nonviolent Protest Effective during the Civil Rights Movement? 11.10 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CHANGE/DOMESTIC ISSUES (1945 – PRESENT): Racial, gender, and New York State socioeconomic inequalities were addressed By individuals, groups, and organizations. Varying political Social Studies philosophies prompted debates over the role of federal government in regulating the economy and providing Framework Key a social safety net. Idea & Practices Gathering, Using, and Interpreting Evidence Chronological Reasoning and Causation Staging the Discuss tHe recent die-in protests and tHe extent to wHicH tHey are an effective form of nonviolent direct- Question action protest. Supporting Question 1 Supporting Question 2 Supporting Question 3 Guided Student Research Independent Student Research What was tHe impact of tHe What made tHe Montgomery Bus How did otHers use nonviolence GreensBoro sit-in protest? boycott, the Birmingham campaign, effectively during tHe civil rights and tHe Selma to Montgomery movement? marcHes effective? Formative Formative Formative Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Create a cause-and-effect diagram tHat Detail tHe impacts of a range of actors Research the impact of a range of demonstrates the impact of the sit-in and tHe actions tHey took to make tHe actors and tHe effective nonviolent protest by the Greensboro Four. -

IN HONOR of FRED GRAY: MAKING CIVIL RIGHTS LAW from ROSA PARKS to the TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY - Introduction

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 67 Issue 4 Article 10 2017 SYMPOSIUM: IN HONOR OF FRED GRAY: MAKING CIVIL RIGHTS LAW FROM ROSA PARKS TO THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY - Introduction Jonathan L. Entin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jonathan L. Entin, SYMPOSIUM: IN HONOR OF FRED GRAY: MAKING CIVIL RIGHTS LAW FROM ROSA PARKS TO THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY - Introduction, 67 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 1025 (2017) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol67/iss4/10 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 67·Issue 4·2017 —Symposium— In Honor of Fred Gray: Making Civil Rights Law from Rosa Parks to the Twenty-First Century Introduction Jonathan L. Entin† Contents I. Background................................................................................ 1026 II. Supreme Court Cases ............................................................... 1027 A. The Montgomery Bus Boycott: Gayle v. Browder .......................... 1027 B. Freedom of Association: NAACP v. Alabama ex rel. Patterson ....... 1028 C. Racial Gerrymandering: Gomillion v. Lightfoot ............................. 1029 D. Constitutionalizing the Law of -

<Billno> <Sponsor>

<BillNo> <Sponsor> HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION 8020 of the Second Extraordinary Session By Clemmons A RESOLUTION to honor the memory of United States Congressman John Robert Lewis. WHEREAS, the members of this General Assembly were greatly saddened to learn of the passing of United States Congressman John Robert Lewis; and WHEREAS, Congressman John Lewis dedicated his life to protecting human rights, securing civil liberties, and building what he called "The Beloved Community" in America; and WHEREAS, referred to as "one of the most courageous persons the Civil Rights Movement ever produced," Congressman Lewis evidenced dedication and commitment to the highest ethical standards and moral principles and earned the respect of his colleagues on both sides of the aisle in the United States Congress; and WHEREAS, John Lewis, the son of sharecropper parents Eddie and Willie Mae Carter Lewis, was born on February 21, 1940, outside of Troy, Alabama, and was raised on his family's farm with nine siblings; and WHEREAS, he attended segregated public schools in Pike County, Alabama, and, in 1957, became the first member of his family to complete high school; he was vexed by the unfairness of racial segregation and disappointed that the Supreme Court's 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education did not affect his and his classmates' experience in public school; and WHEREAS, Congressman Lewis was inspired to work toward the change he wanted to see by Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s sermons and the outcome of the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955 and -

February 6, 2016 Hawaii Filipino Chronicle 1

FeBruary 6, 2016 HawaII FIlIPIno CHronICle 1 ♦ FEBRUARY 6, 2016 ♦ Photo credit: Jason Moore BIG ISLAND MEMORIES LEGAL NOTES NON-FIcTION STORy sakada day In keeau ImmIgratIon raIds Cause love and sInulog FestIval Fear among ImmIgrant knows no In kona CommunItIes Bounds PRESORTED HAWAII FILIPINO cHRONIcLE STANDARD 94-356 WAIPAHU DEPOT RD., 2ND FLR. U.S. POSTAGE WAIPAHU, HI 96797 PAID HONOLULU, HI PERMIT NO. 9661 2 HawaII FIlIPIno CHronICle FeBruary 6, 2016 EDITORIALS FROM THE PUBLISHER Publisher & Executive Editor ung Hee Fat Choy! Just when Charlie Y. Sonido, M.D. More Filipinos Artists the newness and excitement of Publisher & Managing Editor 2016 has faded, there’s Chinese Chona A. Montesines-Sonido Making News New Year to celebrate. So in the Associate Editors Dennis Galolo | Edwin Quinabo ilipinos are headliners in sports, entertainment, spirit of Chinese New Year, K Contributing Editor beauty pageants and politics to name just a few. One which is officially observed on Belinda Aquino, Ph.D. field that tends to be overlooked is fine arts—and February 8, the Chronicle’s staff and edi- Creative Designer understandably so. Art is often an afterthought and torial board would like to wish our readers Junggoi Peralta a luxury in a Third World Country like the Philip- F a very happy, safe and prosperous Year of the Monkey. Photography pines where the majority of the people work extra For this issue’s cover story, contributing writer Carolyn Tim Llena hard to make ends meet. But with the recent successes of a grow- Administrative Assistant Weygan-Hildebrand introduces us to talented Filipino artist Shalimar Pagulayan ing number of Filipino artists, the international art world is notic- Philip Sabado whose paintings have delighted those fortunate columnists ing that pinoys are pretty damn good when it comes to visually enough to see them up-close-and-personal. -

728 of That Tree That Charles Described, and the Leaves, Exactly What to Do

728 of that tree that Charles described, and the leaves, exactly what to do. Chairman SPECTER. Thank you very much, Senator Feinstein. Senator FEINSTEIN. Thank you very much, Mr. Chairman. Chairman SPECTER. We are going to adjourn for a— Senator COBURN. Senator Specter, I will defer my questions so that we will not have to have the panel come back, if that would be OK, and I will submit some questions. Chairman SPECTER. You are entitled to your round. Senator COBURN. But I think in all courtesy to our distinguished panel, this would release them, and I will be happy to submit some questions for the record. Chairman SPECTER. All right. We will proceed in that manner at your suggestion. As I had said earlier, New York Times reporter, David Rosen- baum, a memorial service is being held for him. he was brutally murdered on the streets of Washington very recently. We will re- cess for just a few moments. I would like the next panel to be ready and the Senators to be ready. [Recess at 10:05 a.m. to 10:40 a.m.] Chairman SPECTER. The hearing will resume. The first witness on our next panel, Panel 5, is Mr. Fred Gray, senior partner at Gray, Langford, Sapp, McGowan, Gray & Nathanson, a veteran civil rights attorney with an extraordinary record of representation. At the age of 24, he represented Ms. Rosa Parks, whose involvement in the historic refusal to give up her seat on the bus to a white man is so well known. That action initiated the Montgomery bus boycott. -

Frank W. Ballance, Jr. 1942–

FORMER MEMBERS H 1971–2007 ������������������������������������������������������������������������ Frank W. Ballance, Jr. 1942– UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE H 2003–2004 DEMOCRAT FROM NORTH CAROLINA he first African American elected to the state and, after switching to the Republican Party, for a seat on Tlegislature from eastern North Carolina since the the Warren County Commission in 1974. Ballance soon Reconstruction Era, Frank Ballance won election to the returned to the Democratic Party “to my people, where U.S. House in 2002, succeeding Representative Eva my votes are.”2 In 1982, Ballance became the first black Clayton in a district that included much of coastal North in roughly a century to be elected to the statehouse from Carolina. During an 18-month tenure in the House that the eastern section of the state, defeating a white lawyer was abbreviated by health problems and a probe into his to represent a newly redrawn district. A local newspaper management of a nonprofit foundation, Ballance served on published the story under the headline “Free at Last.” the Agriculture Committee—an important assignment for Ballance recalled, “Among the black community, there his predominantly rural, farm-based constituency. was great excitement that a new day had dawned and Frank Winston Ballance, Jr., was born in Windsor, things would be different.”3 He served from 1983 to 1987 North Carolina, on February 15, 1942, to Frank Winston in the North Carolina state house of representatives. He and Alice Eason Ballance. His mother, noted one political was unsuccessful in his bid for a nomination to the North activist in eastern North Carolina, was the “political wheel” Carolina senate in 1986 but was elected two years later of Bertie County, organizing drives for voter registration and served in the upper chamber from 1989 to 2002. -

IN SULLIVAN's SHADOW: the USE and ABUSE of LIBEL LAW DURING the CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT a Dissertation Presented to the Facult

IN SULLIVAN’S SHADOW: THE USE AND ABUSE OF LIBEL LAW DURING THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by AIMEE EDMONDSON Dr. Earnest L. Perry Jr., Dissertation Supervisor DECEMBER 2008 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled: IN SULLIVAN’S SHADOW: THE USE AND ABUSE OF LIBEL LAW DURING THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT presented by Aimee Edmondson, a candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. ________________________________ Associate Professor Earnest L. Perry Jr. ________________________________ Professor Richard C. Reuben ________________________________ Associate Professor Carol Anderson ________________________________ Associate Professor Charles N. Davis ________________________________ Assistant Professor Yong Volz In loving memory of my father, Ned Edmondson ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It would be impossible to thank everyone responsible for this work, but special thanks should go to Dr. Earnest L. Perry, Jr., who introduced me to a new world and helped me explore it. I could not have asked for a better mentor. I also must acknowledge Dr. Carol Anderson, whose enthusiasm for the work encouraged and inspired me. Her humor and insight made the journey much more fun and meaningful. Thanks also should be extended to Dr. Charles N. Davis, who helped guide me through my graduate program and make this work what it is. To Professor Richard C. Reuben, special thanks for adding tremendous wisdom to the project. Also, much appreciation to Dr. -

The Birmingham Sixteenth Street Baptist Church Bombing and the Legacy of Judge Frank Minis Johnson Jr

Alabama Law Scholarly Commons Essays, Reviews, and Shorter Works Faculty Scholarship 2019 Justice Delayed, Justice Delivered: The Birmingham Sixteenth Street Baptist Church Bombing and the Legacy of Judge Frank Minis Johnson Jr. Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr. Centennial Symposium & Law Clerks Reunion Kenneth M. Rosen University of Alabama - School of Law, [email protected] W. Keith Watkins William J. Baxley George L. Beck Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.ua.edu/fac_essays Recommended Citation Kenneth M. Rosen, W. K. Watkins, William J. Baxley & George L. Beck, Justice Delayed, Justice Delivered: The Birmingham Sixteenth Street Baptist Church Bombing and the Legacy of Judge Frank Minis Johnson Jr. Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr. Centennial Symposium & Law Clerks Reunion, 71 Ala. L. Rev. 601 (2019). Available at: https://scholarship.law.ua.edu/fac_essays/206 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Alabama Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Essays, Reviews, and Shorter Works by an authorized administrator of Alabama Law Scholarly Commons. JUSTICE DELAYED, JUSTICE DELIVERED: THE BIRMINGHAM SIXTEENTH STREET BAPTIST CHURCH BOMBING AND THE LEGACY OF JUDGE FRANK MINIS JOHNSON JR. Kenneth M. Rosen* & Hon. W Keith Watkins** That delayed justice should be avoided in the United States legal system is fundamentally consistent with American aspirations of doing what is morally right. Answering criticism by other clergy of his civil rights activities, in his famed Letterfrom a BirminghamJail, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. referenced a jurist in proclaiming that "justice too long delayed is justice denied."1 The need for urgency in remedying injustice is clear. -

SYMPOSIUM: in HONOR of FRED GRAY: MAKING CIVIL RIGHTS LAW from ROSA PARKS to the TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY - Introduction Jonathan L

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 67 | Issue 4 2017 SYMPOSIUM: IN HONOR OF FRED GRAY: MAKING CIVIL RIGHTS LAW FROM ROSA PARKS TO THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY - Introduction Jonathan L. Entin Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jonathan L. Entin, SYMPOSIUM: IN HONOR OF FRED GRAY: MAKING CIVIL RIGHTS LAW FROM ROSA PARKS TO THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY - Introduction, 67 Case W. Res. L. Rev. 1025 (2017) Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol67/iss4/10 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 67·Issue 4·2017 —Symposium— In Honor of Fred Gray: Making Civil Rights Law from Rosa Parks to the Twenty-First Century Introduction Jonathan L. Entin† Contents I. Background................................................................................ 1026 II. Supreme Court Cases ............................................................... 1027 A. The Montgomery Bus Boycott: Gayle v. Browder .......................... 1027 B. Freedom of Association: NAACP v. Alabama ex rel. Patterson ....... 1028 C. Racial Gerrymandering: Gomillion v. Lightfoot ............................. 1029 D. Constitutionalizing the Law of Defamation: -

BLACK HISTORY NAME FIND “ATTENTION: EARN MONEY TYPING at HOME! 32,000/Yr Income Potential

.y PAGE 16 The News Argus February 1990 QAJOHNJOHNSONBOWPNXJW MPEMARVACOLLI NSAWLKAE AHSAFB EDN XONSUO EMCNB R SRRE LAJCWC LRS.BCBEB TL ECEN TUDZVRR BEV DAJTO I L JUDJ ZSPBROA TOZ UDPBO Is your fraternity, N A5GA PXTABDA LKZ BBBAK sorority or club interested in earning $1,000.00= for a one- L PCGRM JEHE NBMALC OMXLE week, on-campus marketing project? You must be well- U R K A A MLS C W E D E G X B L R organized and hard working. ■> Call Jenny or Myra at (800) T A SRYN AOLLO XZ YZ S ELAT 592-2121 H NOVPH NANDREWYOU N GMRW Wanted!!! Students to join the E DNE5 0 JOURNE RTRU T HFDA 1990 Student Travel Serv ices’ Sales Team. Earn Cash R OXYV 0 NNEKEN NEDY P QNRS and/or FREE Spring Break travel marketing Spring K l'pqn k jam ESF ARMER OBKH Break packages to Jamaica, Cancun, Acapulco, and P M J S W I L L AMCOSBYRC Daytona Beach. For more information call 1-800-648- N H A R R ETTUBM ANM NC ADEN 4849 G DO RO T HYH EIG HTA FP QDVG Instructors needed to teach cheerleading, dance, JBMEDGAREVERSI PAC GYTT gymnastics at summer camp sites. Interviews scheduled RHARVEYGANTTLUSXD N RMO for February 3rd in Greens boro. To schedule an inter WALTE RWHI TEUFOTWO PXON view: CALL 1-800- 33CHEER OR WRITE: Nation-Wide Cheerleaders, c * X PEO D I CNM KJD I AN EN ASHF 2275 Canterbury Offices, Indiana, PA 15701. BLACK HISTORY NAME FIND “ATTENTION: EARN MONEY TYPING AT HOME! 32,000/yr income potential. -

Bus Ride to Justice to There Could Be a Test Case to Challenge Segregation Laws

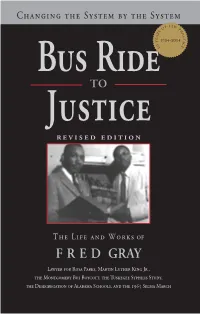

Biography/History/Civil Rights $25.95 FRED Changing the System by the System f law o p r s a irst published in 1995, this best-selling autobiography by acclaimed civil rights r c GRAY a t e attorney Fred D. Gray appears now in a newly revised edition that updates Gray’s i y 1954–2014 c F e 0 remarkable career of “destroying everything segregated that I could find.” Of particular 6 interest will be the details Gray reveals for the first time about Rosa Parks’s 1955 arrest. Gray was the young lawyer for Parks and also Martin Luther King Jr. and the Montgomery Improvement Association, which organized the 382-day Montgomery Bus Boycott after Parks’s arrest. As the last survivor of that inner circle, Gray speaks about the strategic reasons Parks was presented as a demure, random victim of Jim Crow policies when Bus Ride in reality she was a committed, strong-willed activist who was willing to be arrested so Bus Ride to Justice TO there could be a test case to challenge segregation laws. Gray’s remarkable career also includes landmark civil rights cases in voting rights, education, housing, employment, law enforcement, jury selection, and more. He is widely considered one of the most successful civil rights attorneys of the twentieth century and his cases are studied in law schools around the world. In addition he was an ordained Church of Christ minister and was one of the first blacks elected to the Alabama legislature in the modern era. Initially denied entrance to Alabama’s segregated Justice law school, he became the first black president of the Alabama bar association. -

Suspect Citizens

i Suspect Citizens Suspect Citizens offers the most comprehensive look to date at the most common form of police– citizen interactions, the routine traffi c stop. Throughout the war on crime, police agencies have used traffi c stops to search drivers suspected of carrying contraband. From the beginning, police agencies made it clear that very large numbers of police stops would have to occur before an offi cer might interdict a signifi cant drug shipment. Unstated in that calculation was that many Americans would be subjected to police investigations so that a small number of high- level offenders might be found. The key element in this strategy, which kept it hidden from widespread public scrutiny, was that middle- class white Americans were largely exempt from its consequences. Tracking these police practices down to the offi cer level, Suspect Citizens documents the extreme rarity of drug busts and reveals sustained and troubling disparities in how racial groups are treated. Frank R. Baumgartner holds the Richard J. Richardson Distinguished Professorship at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He is a leading scholar of public policy and has written extensively on agenda- setting, policy- making, and lobbying. His work on criminal justice includes two previous books on the death penalty. Derek A. Epp is Assistant Professor of Government at the University of Texas at Austin. In The Structure of Policy Change , he explains how the capacity of governmental institutions to process information affects public policy. He also studies economic inequality with a par- ticular focus on understanding how rising inequality affects govern- ment agendas.