THE BELFAST AGREEMENT a Practical Legal Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women in the Northern Ireland Assembly

Research and Information Service Research Paper 3 September 2013 Michael Potter Women in the Northern Ireland Assembly NIAR 570-13 This paper summarises the background to women’s representation in politics, outlines the legislative frameworks relevant to women’s representation in the Northern Ireland Assembly and reviews some mechanisms for increasing female representation. Paper 09/14 03 September 2013 Research and Information Service briefings are compiled for the benefit of MLAs and their support staff. Authors are available to discuss the contents of these papers with Members and their staff but cannot advise members of the general public. We do, however, welcome written evidence that relates to our papers and this should be sent to the Research and Information Service, Northern Ireland Assembly, Room 139, Parliament Buildings, Belfast BT4 3XX or e-mailed to [email protected] NIAR 570-013 Research Paper Northern Ireland Assembly, Research and Information Service 1 NIAR 570-013 Research Paper Executive Summary With the exception of Dáil Éireann, the Northern Ireland Assembly has the lowest female representation of devolved and national legislatures in these islands. The introduction of quotas for women candidates in the Republic of Ireland in the next election has the potential to alter this situation. In a European context, with the exception of Italian regional legislatures, the Northern Ireland Assembly has the lowest female representation of comparable devolved institutions in Western Europe. International declarations, such as the Beijing Platform for Action in 1995, echoed locally in the Belfast Agreement and the Gender Equality Strategy, recognise the right of women to full and equal political participation. -

The European Community and the Relationships Between Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic: a Test of Neo-Functionalism

Tresspassing on Borders? The European Community and the Relationships between Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic: A Test of Neo-functionalism Etain Tannam Department of Government London School of Economics and Political Science Ph.D. thesis UMI Number: U062758 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U062758 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 or * tawmjn 7/atA K<2lt&8f4&o ii Contents List of Figures v Acknowledgements vi 1. The European Community and the Irish/Northern Irish Cross- 1 border Relationship: Theoretical Framework Introduction 2 1. The Irish/Northern Irish Cross-border Relationship: A Critical 5 Test of Neo-functionalism ii. Co-operation and The Northern Irish/Irish Cross-Border 15 Relationship iii. The Irish/Northern Irish Cross-border Relationship and the 21 Anglo-Irish Agreement iv. The Anglo-Irish Agreement and International Relations Theory 25 Conclusion: The Irish Cross-border Relationship and International 30 Relations Theory: Hypotheses 2. A History ofThe Cross-Border Political Relationship 34 Introduction 35 i. Partition and the Boundary Commission. -

The Jim Kemmy Papers P5

The Jim Kemmy Papers P5 University of Limerick Library and Information Services University of Limerick Special Collections The Jim Kemmy Papers Reference Code: IE 2135 P5 Title: The Jim Kemmy Papers Dates of Creation: 1863-1998 (predominantly 1962-1997) Level of Description: Fonds Extent and Medium: 73 boxes (857 folders) CONTEXT Name of Creator: Kemmy, Seamus (Jim) (1936-1997) Biographical History: Seamus Kemmy, better known as Jim Kemmy, was born in Limerick on 14 September, 1936, as the eldest of five children to Elizabeth Pilkington and stonemason Michael Kemmy. He was educated at the Christian Brothers’ primary school in Sexton Street and in 1952 followed his father into the Ancient Guild of Incorporated Brick and Stonelayers’ Trade Union to commence his five-year apprenticeship. When his father died of tuberculosis in 1955, the responsibility of providing for the family fell onto Kemmy’s shoulders. Having qualified as a stonemason in 1957, he emigrated to England in the hope of a better income. The different social conditions and the freedom of thought and expression he encountered there challenged and changed his traditional Catholic values and opened his eyes to the issues of social injustice and inequality, which he was to stand up against for the rest of his life. In 1960, encouraged by the building boom, Kemmy returned to Ireland and found work on construction sites at Shannon. He also became involved in the Brick and Stonelayers’ Trade Union, and was elected Branch Secretary in 1962. A year later, he joined the Labour Party. Kemmy harboured no electoral ambitions during his early years in politics. -

OFFICIAL REPORT (Hansard)

Ad Hoc Committee on a Bill of Rights OFFICIAL REPORT (Hansard) Mr Dermot Nesbitt 15 October 2020 NORTHERN IRELAND ASSEMBLY Ad Hoc Committee on a Bill of Rights Mr Dermot Nesbitt 15 October 2020 Members present for all or part of the proceedings: Ms Emma Sheerin (Chairperson) Mr Mike Nesbitt (Deputy Chairperson) Ms Paula Bradshaw Mr Mark Durkan Miss Michelle McIlveen Mr Christopher Stalford Mr John O'Dowd Witnesses: Mr Dermot Nesbitt Ulster Unionist Party The Chairperson (Ms Sheerin): Dermot Nesbitt joins us in person to give a briefing on "particular circumstances". Welcome, Dermot, how are you? Mr Dermot Nesbitt (Ulster Unionist Party): Hello, Madam Chair. The Chairperson (Ms Sheerin): Do you want a round of introductions before you start your briefing? Mr D Nesbitt: I am ready, once I unmask. I recognise a few faces — "Oh dear", says I. Hi, Paula, it has been a long time. The Chairperson (Ms Sheerin): Dermot, thanks very much for joining us this afternoon. We all have your written submission, which is useful and all-encompassing. Would you like to begin? Mr D Nesbitt: OK. I see that we have two members on screen. The Chairperson (Ms Sheerin): We do: John O'Dowd and Mark Durkan. Mr D Nesbitt: Hi, John and Mark. Mr O'Dowd: Hi, Dermot. Mr Durkan: Hi, Dermot. Mr D Nesbitt: OK, I am ready to go. I wish to make a couple of introductory comments before I proceed with my main briefing. Paragraph 2 of my submission quotes Professor Brice Dickson, who, when chair of the Human Rights Commission, said: 1 "We are all familiar with the phenomenon of politicians taking a view of human rights which happens to accord with their personal political persuasions rather than with a more independent analysis." At the outset, I wish to say that, during this process since 1998, I have endeavoured to ground my work in international standards and international human rights. -

Official Report (Hansard)

Official Report (Hansard) Tuesday 12 March 2013 Volume 83, No 2 Session 2012-2013 Contents Speaker's Business……………………………………………………………………………………….. 1 Ministerial Statement North/South Ministerial Council: Education ....................................................................................... 2 Executive Committee Business Criminal Justice Bill: Further Consideration Stage ............................................................................ 8 Oral Answers to Questions Education ........................................................................................................................................... 28 Employment and Learning ................................................................................................................. 34 Northern Ireland Assembly Commission ........................................................................................... 40 Executive Committee Business Criminal Justice Bill: Further Consideration Stage (Continued) ........................................................ 47 Adjournment Woodlands Language Unit ................................................................................................................ 88 Written Ministerial Statement Health, Social Services and Public Safety: Follow-on 2012-15 Bamford Action Plan…………… 95 Suggested amendments or corrections will be considered by the Editor. They should be sent to: The Editor of Debates, Room 248, Parliament Buildings, Belfast BT4 3XX. Tel: 028 9052 1135 · e-mail: [email protected] -

A Democratic Design? the Political Style of the Northern Ireland Assembly

A Democratic Design? The political style of the Northern Ireland Assembly Rick Wilford Robin Wilson May 2001 FOREWORD....................................................................................................3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................4 Background.........................................................................................................................................7 Representing the People.....................................................................................................................9 Table 1 Parties Elected to the Assembly ........................................................................................10 Public communication......................................................................................................................15 Table 2 Written and Oral Questions 7 February 2000-12 March 2001*........................................17 Assembly committees .......................................................................................................................20 Table 3 Statutory Committee Meetings..........................................................................................21 Table 4 Standing Committee Meetings ..........................................................................................22 Access to information.......................................................................................................................26 Table 5 Assembly Staffing -

By James King B.A., Samford University, 2006 M.L.I.S., University

THE STRUGGLE CONTINUES: ARCHIVAL APPROACHES TO CIVIL RIGHTS IN NORTHERN IRELAND AND THE AMERICAN SOUTH by James King B.A., Samford University, 2006 M.L.I.S., University of Alabama, 2007 M.A., Boston College, 2009 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Computing and Information in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2018 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF COMPUTING AND INFORMATION This dissertation was presented by James King It was defended on November 16, 2017 and approved by Dr. Sheila Corrall, Professor, Library and Information Science Dr. Andrew Flinn, Reader in Archival Studies and Oral History, Information Studies, University College London Dr. Alison Langmead, Associate Professor, Library and Information Science Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Richard J. Cox, Professor, Library and Information Science ii Copyright © by James King 2018 iii THE STRUGGLE CONTINUES: ARCHIVAL APPROACHES TO CIVIL RIGHTS IN NORTHERN IRELAND AND THE AMERICAN SOUTH James King, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2018 When police and counter-protesters broke up the first march of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) in August 1968, activists sang the African American spiritual, “We Shall Overcome” before disbanding. The spiritual, so closely associated with the earlier civil rights struggle in the United States, was indicative of the historical and material links shared by the movements in Northern Ireland and the American South. While these bonds have been well documented within history and media studies, the relationship between these regions’ archived materials and contemporary struggles remains largely unexplored. While some artifacts from the movements—along with the oral histories and other materials that came later—remained firmly ensconced within the archive, others have been digitally reformatted or otherwise repurposed for a range of educational, judicial, and social projects. -

Revisionism: the Provisional Republican Movement

Journal of Politics and Law March, 2008 Revisionism: The Provisional Republican Movement Robert Perry Phd (Queens University Belfast) MA, MSSc 11 Caractacus Cottage View, Watford, UK Tel: +44 01923350994 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article explores the developments within the Provisional Republican Movement (IRA and Sinn Fein), its politicization in the 1980s, and the Sinn Fein strategy of recent years. It discusses the Provisionals’ ending of the use of political violence and the movement’s drift or determined policy towards entering the political mainstream, the acceptance of democratic norms. The sustained focus of my article is consideration of the revision of core Provisional principles. It analyses the reasons for this revisionism and it considers the reaction to and consequences of this revisionism. Keywords: Physical Force Tradition, Armed Stuggle, Republican Movement, Sinn Fein, Abstentionism, Constitutional Nationalism, Consent Principle 1. Introduction The origins of Irish republicanism reside in the United Irishman Rising of 1798 which aimed to create a democratic society which would unite Irishmen of all creeds. The physical force tradition seeks legitimacy by trying to trace its origin to the 1798 Rebellion and the insurrections which followed in 1803, 1848, 1867 and 1916. Sinn Féin (We Ourselves) is strongly republican and has links to the IRA. The original Sinn Féin was formed by Arthur Griffith in 1905 and was an umbrella name for nationalists who sought complete separation from Britain, as opposed to Home Rule. The current Sinn Féin party evolved from a split in the republican movement in Ireland in the early 1970s. Gerry Adams has been party leader since 1983, and led Sinn Féin in mutli-party peace talks which resulted in the signing of the 1998 Belfast Agreement. -

Orange Alba: the Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland Since 1798

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2010 Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798 Ronnie Michael Booker Jr. University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Booker, Ronnie Michael Jr., "Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2010. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/777 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Ronnie Michael Booker Jr. entitled "Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in History. John Bohstedt, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Vejas Liulevicius, Lynn Sacco, Daniel Magilow Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by R. -

Ireland As a Centre of Excellence in Third Level Education: Challenges for the Universities 25

Ireland as a Centre of Excellence in Third Level Education The Centre for Cross Border Studies Main Office: 39 Abbey Street, Armagh BT61 7EB Tel. (028) 3751 1550 Fax. (028) 3751 1721 (048 from the Republic of Ireland) Email: [email protected] Dublin Office: Room QG11, Business School, Dublin City University, Dublin 9 Tel. (01) 7008477 Fax. (01) 7008478 (00 353-1 from Northern Ireland) Email: [email protected] Website: www.crossborder.ie or www.qub.ac.uk/ccbs 2 CONTENTS Page Introduction by Olivia O’Leary 5 Ms Carmel Hanna MLA, Minister for Employment and Learning 7 Mr Noel Dempsey TD, Minister for Education and Science 11 Sir Howard Newby, Chief Executive, Higher Education Funding Council for England Higher Education in the 21st Century: An English Perspective 15 Professor Malcolm Skilbeck, Keynote Speaker Ireland as a Centre of Excellence in Third Level Education: Challenges for the Universities 25 Professor Gearóid Ó Tuathaigh, NUI Galway Response to Malcolm Skilbeck’s paper 31 Questions and Discussion: First Day Chaired by Olivia O’Leary 39 Mr Richard Riley, Former US Secretary of Education and Former Governor of South Carolina American Higher Education in a Diverse World 53 Mr Nikolaus van der Pas, Director-General for Education and Culture of the European Commission Higher Education: The European Dimension and Beyond 61 Closing Discussion: Second Day Chaired by Dr Art Cosgrove, President, NUI Dublin 67 Closing Remarks, Professor Gerry McCormac, Pro-Vice-Chancellor, Queen’s University Belfast 81 Appendix 1: A Briefing Paper on the Irish Third Level Education Systems, North and South 83 Appendix 2: Conference Programme: Ireland as a Centre of Excellence in Third Level Education 99 Appendix 3: Biographies of Speakers and Chairpersons 101 Appendix 4: Conference Participants 105 3 4 INTRODUCTION If cross-border co-operation were going to develop anywhere, one would have expected it in the enlightened sphere of third level education. -

Introduction to the Brookeborough Papers Adobe

INTRODUCTION BROOKEBOROUGH PAPERS November 2007 Brookeborough Papers (D3004 and D998) Table of Contents Summary .................................................................................................................3 Family history...........................................................................................................4 Plantation Donegal ..................................................................................................5 The Brookes come to Fermanagh ...........................................................................6 The last of the Donegal Brookes..............................................................................7 The Brookes of Colebrooke, c.1685-1761 ...............................................................8 Sir Arthur Brooke, Bt (c.1715-1785).........................................................................9 Major Francis Brooke (c.1720-1800) and his family...............................................10 General Sir Arthur Brooke (1772-1843) .................................................................11 Colonel Francis Brooke (c.1770-1826) ..................................................................12 Major Francis Brooke's other children....................................................................13 Recovery over two generations, 1785-1834 ..........................................................14 The military tradition of the Brookes ......................................................................15 Politics and local government -

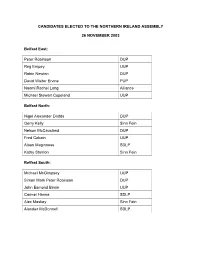

Peter Robinson DUP Reg Empey UUP Robin Newton DUP David Walter Ervine PUP Naomi Rachel Long Alliance Michael Stewart Copeland UUP

CANDIDATES ELECTED TO THE NORTHERN IRELAND ASSEMBLY 26 NOVEMBER 2003 Belfast East: Peter Robinson DUP Reg Empey UUP Robin Newton DUP David Walter Ervine PUP Naomi Rachel Long Alliance Michael Stewart Copeland UUP Belfast North: Nigel Alexander Dodds DUP Gerry Kelly Sinn Fein Nelson McCausland DUP Fred Cobain UUP Alban Maginness SDLP Kathy Stanton Sinn Fein Belfast South: Michael McGimpsey UUP Simon Mark Peter Robinson DUP John Esmond Birnie UUP Carmel Hanna SDLP Alex Maskey Sinn Fein Alasdair McDonnell SDLP Belfast West: Gerry Adams Sinn Fein Alex Atwood SDLP Bairbre de Brún Sinn Fein Fra McCann Sinn Fein Michael Ferguson Sinn Fein Diane Dodds DUP East Antrim: Roy Beggs UUP Sammy Wilson DUP Ken Robinson UUP Sean Neeson Alliance David William Hilditch DUP Thomas George Dawson DUP East Londonderry: Gregory Campbell DUP David McClarty UUP Francis Brolly Sinn Fein George Robinson DUP Norman Hillis UUP John Dallat SDLP Fermanagh and South Tyrone: Thomas Beatty (Tom) Elliott UUP Arlene Isobel Foster DUP* Tommy Gallagher SDLP Michelle Gildernew Sinn Fein Maurice Morrow DUP Hugh Thomas O’Reilly Sinn Fein * Elected as UUP candidate, became a member of the DUP with effect from 15 January 2004 Foyle: John Mark Durkan SDLP William Hay DUP Mitchel McLaughlin Sinn Fein Mary Bradley SDLP Pat Ramsey SDLP Mary Nelis Sinn Fein Lagan Valley: Jeffrey Mark Donaldson DUP* Edwin Cecil Poots DUP Billy Bell UUP Seamus Anthony Close Alliance Patricia Lewsley SDLP Norah Jeanette Beare DUP* * Elected as UUP candidate, became a member of the DUP with effect from