Comparative Efficacy and Acceptability of Pharmacological Treatments for Insomnia in Adults: a Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis (Protocol)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proposed Regulation of the State Board of Pharmacy

PROPOSED REGULATION OF THE STATE BOARD OF PHARMACY LCB File No. R133-14 Workshop July 24, 2014 NAC 453.540 Schedule IV. (NRS 453.146, 639.070) 1. Schedule IV consists of the drugs and other substances listed in this section, by whatever official, common, usual, chemical or trade name designated. 2. Unless specifically excepted or unless listed in another schedule, any material, compound, mixture or preparation containing any of the following narcotic drugs, including, without limitation, their salts, calculated as the free anhydrous base of alkaloid, is hereby enumerated on schedule IV, in quantities: (a) Not more than 1 milligram of difenoxin and not less than 25 micrograms of atropine sulfate per dosage unit; or (b) Dextropropoxyphene (alpha-(+)-4-dimethylamino-1,2-diphenyl-3-methyl-2-propionoxy- butane). 3. Unless specifically excepted or unless listed in another schedule, any material, compound, mixture or preparation which contains any quantity of the following substances, including, without limitation, their salts, isomers and salts of isomers, is hereby enumerated on schedule IV, whenever the existence of such salts, isomers and salts of isomers is possible within the specific chemical designation: Alprazolam; Barbital; Bromazepam; Butorphanol; Camazepam; Carisoprodol; Chloral betaine; Chloral hydrate; Chlordiazepoxide; Clobazam; Clonazepam; Clorazepate; Clotiazepam; Cloxazolam; Delorazepam; Diazepam; Dichloralphenazone; Estazolam; Ethchlorvynol; Ethyl loflazepate; Fludiazepam; Flunitrazepam; --1-- Agency Draft of Proposed Regulation R133-14 Flurazepam; Halazepam; Haloxazolam; Ketazolam; Loprazolam; Lorazepam; Lormetazepam; Mebutamate; Medazepam; Meprobamate; Methohexital; Methylphenobarbital (mephobarbital); Midazolam; Nimetazepam; Nitrazepam; Nordiazepam; Oxazepam; Oxazolam; Paraldehyde; Petrichloral; Phenobarbital; Pinazepam; Prazepam; Quazepam; Tramadol (2-((dimethylamino)methyl)-1-(3-methoxyphenyl)cyclohexanol) Temazepam; Tetrazepam; Triazolam; Zaleplon; Zolpidem; or Zopiclone. -

Analytical Methods for Determination of Benzodiazepines. a Short Review

Cent. Eur. J. Chem. • 12(10) • 2014 • 994-1007 DOI: 10.2478/s11532-014-0551-1 Central European Journal of Chemistry Analytical methods for determination of benzodiazepines. A short review Review Article Paulina Szatkowska1, Marcin Koba1*, Piotr Kośliński1, Jacek Wandas1, Tomasz Bączek2,3 1Department of Toxicology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Collegium Medicum of Nicolaus Copernicus University, 85-089 Bydgoszcz, Poland 2Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, Medical University of Gdańsk, 80-416 Gdańsk, Poland 3Institute of Health Sciences, Division of Human Anatomy and Physiology, Pomeranian University of Słupsk, 76-200 Słupsk, Poland Received 16 July 2013; Accepted 6 February 2014 Abstract: Benzodiazepines (BDZs) are generally commonly used as anxiolytic and/or hypnotic drugs as a ligand of the GABAA-benzodiazepine receptor. Moreover, some of benzodiazepines are widely used as an anti-depressive and sedative drugs, and also as anti-epileptic drugs and in some cases can be useful as an adjunct treatment in refractory epilepsies or anti-alcoholic therapy. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) methods, thin-layer chromatography (TLC) methods, gas chromatography (GC) methods, capillary electrophoresis (CE) methods and some of spectrophotometric and spectrofluorometric methods were developed and have been extensively applied to the analysis of number of benzodiazepine derivative drugs (BDZs) providing reliable and accurate results. The available chemical methods for the determination of BDZs in biological materials and pharmaceutical formulations are reviewed in this work. Keywords: Analytical methods • Benzodiazepines • Drugs analysis • Pharmaceutical formulations © Versita Sp. z o.o. 1. Introduction and long). For this reason, an application of these drugs became broader allowing their utility to a larger extent, Benzodiazepines have been first introduced into medical and at the same time, problems related to drug abuse practice in the 60s of the last century. -

124.210 Schedule IV — Substances Included. 1

1 CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES, §124.210 124.210 Schedule IV — substances included. 1. Schedule IV shall consist of the drugs and other substances, by whatever official name, common or usual name, chemical name, or brand name designated, listed in this section. 2. Narcotic drugs. Unless specifically excepted or unless listed in another schedule, any material, compound, mixture, or preparation containing any of the following narcotic drugs, or their salts calculated as the free anhydrous base or alkaloid, in limited quantities as set forth below: a. Not more than one milligram of difenoxin and not less than twenty-five micrograms of atropine sulfate per dosage unit. b. Dextropropoxyphene (alpha-(+)-4-dimethylamino-1,2-diphenyl-3-methyl-2- propionoxybutane). c. 2-[(dimethylamino)methyl]-1-(3-methoxyphenyl)cyclohexanol, its salts, optical and geometric isomers and salts of these isomers (including tramadol). 3. Depressants. Unless specifically excepted or unless listed in another schedule, any material, compound, mixture, or preparation which contains any quantity of the following substances, including its salts, isomers, and salts of isomers whenever the existence of such salts, isomers, and salts of isomers is possible within the specific chemical designation: a. Alprazolam. b. Barbital. c. Bromazepam. d. Camazepam. e. Carisoprodol. f. Chloral betaine. g. Chloral hydrate. h. Chlordiazepoxide. i. Clobazam. j. Clonazepam. k. Clorazepate. l. Clotiazepam. m. Cloxazolam. n. Delorazepam. o. Diazepam. p. Dichloralphenazone. q. Estazolam. r. Ethchlorvynol. s. Ethinamate. t. Ethyl Loflazepate. u. Fludiazepam. v. Flunitrazepam. w. Flurazepam. x. Halazepam. y. Haloxazolam. z. Ketazolam. aa. Loprazolam. ab. Lorazepam. ac. Lormetazepam. ad. Mebutamate. ae. Medazepam. af. Meprobamate. ag. Methohexital. ah. Methylphenobarbital (mephobarbital). -

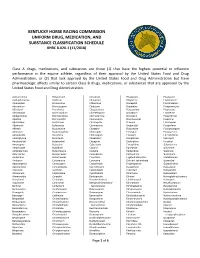

Drug and Medication Classification Schedule

KENTUCKY HORSE RACING COMMISSION UNIFORM DRUG, MEDICATION, AND SUBSTANCE CLASSIFICATION SCHEDULE KHRC 8-020-1 (11/2018) Class A drugs, medications, and substances are those (1) that have the highest potential to influence performance in the equine athlete, regardless of their approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration, or (2) that lack approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration but have pharmacologic effects similar to certain Class B drugs, medications, or substances that are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Acecarbromal Bolasterone Cimaterol Divalproex Fluanisone Acetophenazine Boldione Citalopram Dixyrazine Fludiazepam Adinazolam Brimondine Cllibucaine Donepezil Flunitrazepam Alcuronium Bromazepam Clobazam Dopamine Fluopromazine Alfentanil Bromfenac Clocapramine Doxacurium Fluoresone Almotriptan Bromisovalum Clomethiazole Doxapram Fluoxetine Alphaprodine Bromocriptine Clomipramine Doxazosin Flupenthixol Alpidem Bromperidol Clonazepam Doxefazepam Flupirtine Alprazolam Brotizolam Clorazepate Doxepin Flurazepam Alprenolol Bufexamac Clormecaine Droperidol Fluspirilene Althesin Bupivacaine Clostebol Duloxetine Flutoprazepam Aminorex Buprenorphine Clothiapine Eletriptan Fluvoxamine Amisulpride Buspirone Clotiazepam Enalapril Formebolone Amitriptyline Bupropion Cloxazolam Enciprazine Fosinopril Amobarbital Butabartital Clozapine Endorphins Furzabol Amoxapine Butacaine Cobratoxin Enkephalins Galantamine Amperozide Butalbital Cocaine Ephedrine Gallamine Amphetamine Butanilicaine Codeine -

Report on the Investigation Results

Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency This English version is intended to be a reference material to provide convenience for users. In the event of inconsistency between the Japanese original and this English translation, the former shall prevail. Report on the Investigation Results February 28, 2017 Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency I. Overview of Product [Non-proprietary name] See Attachment 1 [Brand name] See Attachment 1 [Approval holder] See Attachment 1 [Indications] See Attachment 1 [Dosage and administration] See Attachment 1 [Investigating office] Office of Safety II 1 Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency This English version is intended to be a reference material to provide convenience for users. In the event of inconsistency between the Japanese original and this English translation, the former shall prevail. II. Background of the investigation 1. Status in Japan Hypnotics and anxiolytics are prescribed by various specialties and widely used in clinical practice. In particular, benzodiazepine (BZ) receptor agonists, which act on BZ receptors, bind to gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)A-BZ receptor complex and enhance the function of GABAA receptors. This promotes neurotransmission of inhibitory systems and demonstrates hypnotic/sedative effects, anxiolytic effects, muscle relaxant effects, and antispasmodic effects. Since the approval of chlordiazepoxide in March 1961, many BZ receptor agonists have been approved as hypnotics and anxiolytics. Currently, hypnotics and anxiolytics are causative agents of drug-related disorders such as drug dependence in Japanese clinical practice. Hypnotics and anxiolitics that rank high in causative agents are BZ receptor agonists for which high frequencies of high doses and multidrug prescriptions have been reported (Japanese Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 2013; 16(6): 803-812, Modern Physician 2014; 34(6): 653-656, etc.). -

A Review of the Evidence of Use and Harms of Novel Benzodiazepines

ACMD Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs Novel Benzodiazepines A review of the evidence of use and harms of Novel Benzodiazepines April 2020 1 Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 4 2. Legal control of benzodiazepines .......................................................................................... 4 3. Benzodiazepine chemistry and pharmacology .................................................................. 6 4. Benzodiazepine misuse............................................................................................................ 7 Benzodiazepine use with opioids ................................................................................................... 9 Social harms of benzodiazepine use .......................................................................................... 10 Suicide ............................................................................................................................................. 11 5. Prevalence and harm summaries of Novel Benzodiazepines ...................................... 11 1. Flualprazolam ......................................................................................................................... 11 2. Norfludiazepam ....................................................................................................................... 13 3. Flunitrazolam .......................................................................................................................... -

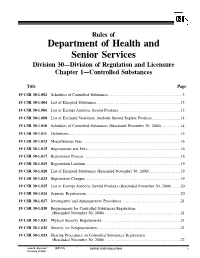

19 CSR 30-1.042 Inventory Requirements

Rules of Department of Health and Senior Services Division 30—Division of Regulation and Licensure Chapter 1—Controlled Substances Title Page 19 CSR 30-1.002 Schedules of Controlled Substances .........................................................3 19 CSR 30-1.004 List of Excepted Substances.................................................................13 19 CSR 30-1.006 List of Exempt Anabolic Steroid Products................................................13 19 CSR 30-1.008 List of Excluded Veterinary Anabolic Steroid Implant Products......................14 19 CSR 30-1.010 Schedules of Controlled Substances (Rescinded November 30, 2000)...............14 19 CSR 30-1.011 Definitions......................................................................................15 19 CSR 30-1.013 Miscellaneous Fees ...........................................................................16 19 CSR 30-1.015 Registrations and Fees........................................................................16 19 CSR 30-1.017 Registration Process ..........................................................................16 19 CSR 30-1.019 Registration Location.........................................................................19 19 CSR 30-1.020 List of Excepted Substances (Rescinded November 30, 2000)........................19 19 CSR 30-1.023 Registration Changes .........................................................................19 19 CSR 30-1.025 List of Exempt Anabolic Steroid Products (Rescinded November 30, 2000).......20 19 CSR 30-1.026 -

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DIX to the HTSUS—Continued

20558 Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DEPARMENT OF THE TREASURY Services, U.S. Customs Service, 1301 TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL APPEN- Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DIX TO THE HTSUSÐContinued Customs Service D.C. 20229 at (202) 927±1060. CAS No. Pharmaceutical [T.D. 95±33] Dated: April 14, 1995. 52±78±8 ..................... NORETHANDROLONE. A. W. Tennant, 52±86±8 ..................... HALOPERIDOL. Pharmaceutical Tables 1 and 3 of the Director, Office of Laboratories and Scientific 52±88±0 ..................... ATROPINE METHONITRATE. HTSUS 52±90±4 ..................... CYSTEINE. Services. 53±03±2 ..................... PREDNISONE. 53±06±5 ..................... CORTISONE. AGENCY: Customs Service, Department TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL 53±10±1 ..................... HYDROXYDIONE SODIUM SUCCI- of the Treasury. NATE. APPENDIX TO THE HTSUS 53±16±7 ..................... ESTRONE. ACTION: Listing of the products found in 53±18±9 ..................... BIETASERPINE. Table 1 and Table 3 of the CAS No. Pharmaceutical 53±19±0 ..................... MITOTANE. 53±31±6 ..................... MEDIBAZINE. Pharmaceutical Appendix to the N/A ............................. ACTAGARDIN. 53±33±8 ..................... PARAMETHASONE. Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the N/A ............................. ARDACIN. 53±34±9 ..................... FLUPREDNISOLONE. N/A ............................. BICIROMAB. 53±39±4 ..................... OXANDROLONE. United States of America in Chemical N/A ............................. CELUCLORAL. 53±43±0 -

Title Continuation and Discontinuation of Benzodiazepine Prescriptions: A

Continuation and discontinuation of benzodiazepine Title prescriptions: A cohort study based on a large claims database in Japan( Dissertation_全文 ) Author(s) Takeshima, Nozomi Citation 京都大学 Issue Date 2016-05-23 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/doctor.k19890 Right Type Thesis or Dissertation Textversion ETD Kyoto University Psychiatry Research ∎ (∎∎∎∎) ∎∎∎–∎∎∎ Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Psychiatry Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/psychres Continuation and discontinuation of benzodiazepine prescriptions: A cohort study based on A large claims database in Japan Nozomi Takeshima, Yusuke Ogawa, Yu Hayasaka, Toshi A Furukawa n Department of Health Promotion and Human Behavior, Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine/School of Public Health, Yoshida Konoe-cho, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan article info abstract Article history: Although benzodiazepines (BZDs) are often prescribed to treat a wide range of psychiatric and neuro- Received 29 March 2015 logical conditions, they are also associated with various harms and risks including dependence. However Received in revised form the frequency of its continued use in the real world has not been well studied, especially at longer follow- 15 October 2015 ups. The aim of this study was to clarify the frequency of long-term BZD use among new BZD users over Accepted 15 January 2016 longer follow-ups and to identify its predictors. We conducted a cohort study to examine how frequently new BZD users became chronic users, based on a large claims database in Japan from January 2005 to Keywords: June 2014. We used Cox proportional hazards models to identify potential predictors. A total 84,412 Benzodiazepine patients with new BZD prescriptions were included in our cohort. -

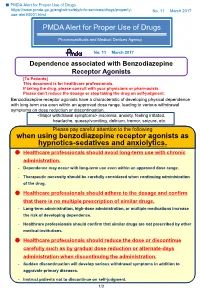

PMDA Alert for Proper Use of Drugs When Using Benzodiazepine

■ PMDA Alert for Proper Use of Drugs https://www.pmda.go.jp/english/safety/info-services/drugs/properly- No. 11 March 2017 use-alert/0001.html PMDA Alert for Proper Use of Drugs Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency No. 11 March 2017 Dependence associated with Benzodiazepine Receptor Agonists [To Patients] This document is for healthcare professionals. If taking the drug, please consult with your physicians or pharmacists. Please don’t reduce the dosage or stop taking the drug on self-judgment. Benzodiazepine receptor agonists have a characteristic of developing physical dependence with long-term use even within an approved dose range, leading to various withdrawal symptoms on dose reduction or discontinuation. <Major withdrawal symptoms> insomnia, anxiety, feeling irritated, headache, queasy/vomiting, delirium, tremor, seizure, etc. Please pay careful attention to the following when using benzodiazepine receptor agonists as hypnotics-sedatives and anxiolytics. Healthcare professionals should avoid long-term use with chronic administration. - Dependence may occur with long-term use even within an approved dose range. - Therapeutic necessity should be carefully considered when continuing administration of the drug. Healthcare professionals should adhere to the dosage and confirm that there is no multiple prescription of similar drugs. - Long-term administration, high-dose administration, or multiple medications increase the risk of developing dependence. - Healthcare professionals should confirm that similar drugs are not prescribed by other medical institutions. Healthcare professionals should reduce the dose or discontinue carefully such as by gradual dose reduction or alternate-days administration when discontinuing the administration. - Sudden discontinuation will develop serious withdrawal symptoms in addition to aggravate primary diseases. -

A. Schedule IV Shall Consist Of

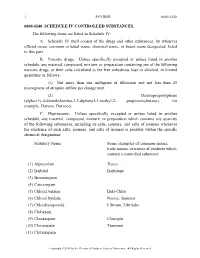

1 REVISOR 6800.4240 6800.4240 SCHEDULE IV CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES. The following items are listed in Schedule IV: A. Schedule IV shall consist of the drugs and other substances, by whatever official name, common or usual name, chemical name, or brand name designated, listed in this part. B. Narcotic drugs. Unless specifically excepted or unless listed in another schedule, any material, compound, mixture, or preparation containing any of the following narcotic drugs, or their salts calculated as the free anhydrous base or alkaloid, in limited quantities as follows: (1) Not more than one milligram of difenoxin and not less than 25 micrograms of atropine sulfate per dosage unit. (2) Dextropropoxyphene (alpha-(+)-4-dimethylamino-1,2-diphenyl-3-methyl-2- propionoxybutane), for example, Darvon, Darvocet. C. Depressants. Unless specifically excepted or unless listed in another schedule, any material, compound, mixture, or preparation which contains any quantity of the following substances, including its salts, isomers, and salts of isomers whenever the existence of such salts, isomers, and salts of isomers is possible within the specific chemical designation: Statutory Name Some examples of common names, trade names, or names of products which contain a controlled substance (1) Alprazolam Xanax (2) Barbital Barbitone (3) Bromazepam (4) Camazepam (5) Chloral betaine Beta-Chlor (6) Chloral hydrate Noctec, Somnos (7) Chlordiazepoxide Librium, Libritabs (8) Clobazam (9) Clonazepam Clonopin (10) Clorazepate Tranxene (11) Clotiazepam Copyright ©2013 -

Screening Colour Test and Specific Colour Tests for the Detection of Methylendioxyamphetamine and Amphetamine Type Stimulants

SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL NOTES SCITEC 16 2009 Screening Colour Test and Specific Colour Tests for the Detection of Methylendioxyamphetamine and Amphetamine Type Stimulants Laboratory and Scientific Section, Division of Policy Analysis 1. Introduction The term amphetamine type stimulants (ATS) refer to a range of drugs mostly derived from the phenethylamines. Amphetamines are central nervous system (CNS) stimulants that were first synthesised more than a century ago for medical applications, but are currently mostly found on illicit drug markets. Globally, ATS use occurs in a range of contexts, and for a variety of purposes. Both recreational and occupational reasons may determine initial use; and use may occur in public settings (e.g., nightclubs), private parties, work environments or as sex aids. In this respect, ATS have demonstrated their attractiveness in a very wide range of situations that seem to differ across countries. ATS are used recreationally to experience the drug’s effects of increased sociability, loss of inhibitions, a sense of escape, or to enhance sexual encounters30‐34. In many high income countries, users typically have a history of other drug use and may use other substances in combination with M/A35‐38. M/A is sometimes used in occupational settings to sustain long work hours and to increase energy and productivity. Examples of this include use by jade‐mine workers in Myanmar, sex workers in Cambodia (Chouvy & Meissonnier, 2004), truck drivers73 159‐161 and even pilots in armed forces, where it has been provided by Governments (Emonson & Vanderbeek, 1995). Amphetamine (AMPT) and methamphetamine (MAMPT) both increase the release of dopamine, noradrenalin, adrenaline and serotonin (Seiden, Sobol, & Ricaurte, 1993; World Health Organization, 2004), stimulate the central nervous system, and have a range of effects including increased energy, feelings of euphoria, decreased appetite, elevated blood pressure and increased heart rate.