The Legacy of Arieh Sharon's Vision of the Israeli

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 the NACOEJ/Edward G

2015 The NACOEJ/Edward G. Victor High School Sponsorship Program We’re delighted to bring you the 10th issue of Bridges, In 1997 the Kasai family left their village in created especially for you. Gondar, embarking on a long, ʅ Besides enjoying the stories There they were welcomed at the NACOEJ here, we hope you will also Compound, which included a serve as an Ambassador for school for their children, food, adult Ethiopian-Israeli high school education, employment and a synagogue for students by passing this the family. Their daughter Rivka was born in newsletter to friends and family Addis Ababa. who might want to support our students. Your endorsement Not until Israel Independence Day in 2005 will help ensure that more was the family able to immigrate to Israel, deserving Ethiopian teens get starting their new life in an absorption center the good education that is the in Safed where Rivka entered 3rd grade. key to success in their futures. Leah Barkai (left) and Rivka Kasai (right) continued inside Questions? Comments? Call Karen Gens at 212-233- 5200, Ext. 230 or email her at [email protected]. She’ll answer questions, contact potential sponsors, and chat (Right) Diana Yacobi shares a special with you about the joys of high moment with one of her sponsored high school sponsorship (she’s been school students, Leah Mekonen. a sponsor for years). And if Diana and her husband Avi visited Leah you have news to share about and their other students at the AMIT your sponsored student, please School in Kiryat Malachi. -

Combined Loss of LAP1B and LAP1C Results in an Early Onset Multisystemic Nuclear Envelopathy

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08493-7 OPEN Combined loss of LAP1B and LAP1C results in an early onset multisystemic nuclear envelopathy Boris Fichtman1, Fadia Zagairy1, Nitzan Biran1, Yiftah Barsheshet1, Elena Chervinsky2, Ziva Ben Neriah3, Avraham Shaag4, Michael Assa1, Orly Elpeleg4, Amnon Harel 1 & Ronen Spiegel5,6 Nuclear envelopathies comprise a heterogeneous group of diseases caused by mutations in genes encoding nuclear envelope proteins. Mutations affecting lamina-associated polypep- 1234567890():,; tide 1 (LAP1) result in two discrete phenotypes of muscular dystrophy and progressive dystonia with cerebellar atrophy. We report 7 patients presenting at birth with severe pro- gressive neurological impairment, bilateral cataract, growth retardation and early lethality. All the patients are homozygous for a nonsense mutation in the TOR1AIP1 gene resulting in the loss of both protein isoforms LAP1B and LAP1C. Patient-derived fibroblasts exhibit changes in nuclear envelope morphology and large nuclear-spanning channels containing trapped cytoplasmic organelles. Decreased and inefficient cellular motility is also observed in these fibroblasts. Our study describes the complete absence of both major human LAP1 isoforms, underscoring their crucial role in early development and organogenesis. LAP1-associated defects may thus comprise a broad clinical spectrum depending on the availability of both isoforms in the nuclear envelope throughout life. 1 Azrieli Faculty of Medicine, Bar-Ilan University, Safed, Israel. 2 Genetic Institute, Emek Medical Center, Afula, Israel. 3 Department of Human Genetics, Shaare Zedek Medical Center, Jerusalem, Israel. 4 Monique and Jacques Roboh Department of Genetic Research, Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center, Jerusalem, Israel. 5 Department of Pediatrics B’, Emek Medical Center, Afula, Israel. -

Pdf, 366.38 Kb

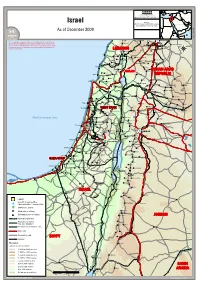

FF II CC SS SS Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services Israel Sources: UNHCR, Global Insight digital mapping © 1998 Europa Technologies Ltd. As of December 2009 Israel_Atlas_A3PC.WOR Dahr al Ahmar Jarba The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the 'Aramtah Ma'adamiet Shih Harran al 'Awamid Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, Qatana Haouch Blass 'Artuz territory, city or area of its authorities or concerning the delimitation of its Najha frontiers or boundaries LEBANON Al Kiswah Che'baâ Douaïr Al Khiyam Metulla Sa`sa` ((( Kafr Dunin Misgav 'Am Jubbata al Khashab ((( Qiryat Shemons Chakra Khan ar Rinbah Ghabaqhib Rshaf Timarus Bent Jbail((( Al Qunaytirah Djébab Nahariyya El Harra ((( Dalton An Namir SYRIAN ARAB Jacem Hatzor GOLANGOLAN Abu-Senan GOLANGOLAN Ar Rama Acre ((( Boutaiha REPUBLIC Bi'nah Sahrin Tamra Shahba Tasil Ash Shaykh Miskin ((( Kefar Hittim Bet Haifa ((( ((( ((( Qiryat Motzkin ((( ((( Ibta' Lavi Ash Shajarah Dâail Kafr Kanna As Suwayda Ramah Kafar Kama Husifa Ath Tha'lah((( ((( ((( Masada Al Yadudah Oumm Oualad ((( ((( Saïda 'Afula ((( ((( Dar'a Al Harisah ((( El 'Azziya Irbid ((( Al Qrayyah Pardes Hanna Besan Salkhad ((( ((( ((( Ya'bad ((( Janin Hadera ((( Dibbin Gharbiya El-Ne'aime Tisiyah Imtan Hogla Al Manshiyah ((( ((( Kefar Monash El Aânata Netanya ((( WESTWEST BANKBANK WESTWEST BANKBANKTubas 'Anjara Khirbat ash Shawahid Al Qar'a' -

Israel-Hizbullah Conflict: Victims of Rocket Attacks and IDF Casualties July-Aug 2006

My MFA MFA Terrorism Terror from Lebanon Israel-Hizbullah conflict: Victims of rocket attacks and IDF casualties July-Aug 2006 Search Israel-Hizbullah conflict: Victims of rocket E-mail to a friend attacks and IDF casualties Print the article 12 Jul 2006 Add to my bookmarks July-August 2006 Since July 12, 43 Israeli civilians and 118 IDF soldiers have See also MFA newsletter been killed. Hizbullah attacks northern Israel and Israel's response About the Ministry (Note: The figure for civilians includes four who died of heart attacks during rocket attacks.) MFA events Foreign Relations Facts About Israel July 12, 2006 Government - Killed in IDF patrol jeeps: Jerusalem-Capital Sgt.-Maj.(res.) Eyal Benin, 22, of Beersheba Treaties Sgt.-Maj.(res.) Shani Turgeman, 24, of Beit Shean History of Israel Sgt.-Maj. Wassim Nazal, 26, of Yanuah Peace Process - Tank crew hit by mine in Lebanon: Terrorism St.-Sgt. Alexei Kushnirski, 21, of Nes Ziona Anti-Semitism/Holocaust St.-Sgt. Yaniv Bar-on, 20, of Maccabim Israel beyond politics Sgt. Gadi Mosayev, 20, of Akko Sgt. Shlomi Yirmiyahu, 20, of Rishon Lezion Int'l development MFA Publications - Killed trying to retrieve tank crew: Our Bookmarks Sgt. Nimrod Cohen, 19, of Mitzpe Shalem News Archive MFA Library Eyal Benin Shani Turgeman Wassim Nazal Nimrod Cohen Alexei Kushnirski Yaniv Bar-on Gadi Mosayev Shlomi Yirmiyahu July 13, 2006 Two Israelis were killed by Katyusha rockets fired by Hizbullah: Monica Seidman (Lehrer), 40, of Nahariya was killed in her home; Nitzo Rubin, 33, of Safed, was killed while on his way to visit his children. -

Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs Between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948

[Intelligence Service (Arab Section)] June 30, 1948 Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948 Contents 1. General introduction. 2. Basic figures on Arab migration 3. National phases of evacuation and migration 4. Causes of Arab migration 5. Arab migration trajectories and absorption issues Annexes 1. Regional reviews analyzing migration issues in each area [Missing from document] 2. Charts of villages evacuated by area, noting the causes for migration and migration trajectories for every village General introduction The purpose of this overview is to attempt to evaluate the intensity of the migration and its various development phases, elucidate the different factors that impacted population movement directly and assess the main migration trajectories. Of course, given the nature of statistical figures in Eretz Yisrael in general, which are, in themselves, deficient, it would be difficult to determine with certainty absolute numbers regarding the migration movement, but it appears that the figures provided herein, even if not certain, are close to the truth. Hence, a margin of error of ten to fifteen percent needs to be taken into account. The figures on the population in the area that lies outside the State of Israel are less accurate, and the margin of error is greater. This review summarizes the situation up until June 1st, 1948 (only in one case – the evacuation of Jenin, does it include a later occurrence). Basic figures on Arab population movement in Eretz Yisrael a. At the time of the UN declaration [resolution] regarding the division of Eretz Yisrael, the following figures applied within the borders of the Hebrew state: 1. -

The Land of Israel Symbolizes a Union Between the Most Modern Civilization and a Most Antique Culture. It Is the Place Where

The Land of Israel symbolizes a union between the most modern civilization and a most antique culture. It is the place where intellect and vision, matter and spirit meet. Erich Mendelsohn The Weizmann Institute of Science is one of Research by Institute scientists has led to the develop- the world’s leading multidisciplinary basic research ment and production of Israel’s first ethical (original) drug; institutions in the natural and exact sciences. The the solving of three-dimensional structures of a number of Institute’s five faculties – Mathematics and Computer biological molecules, including one that plays a key role in Science, Physics, Chemistry, Biochemistry and Biology Alzheimer’s disease; inventions in the field of optics that – are home to 2,600 scientists, graduate students, have become the basis of virtual head displays for pilots researchers and administrative staff. and surgeons; the discovery and identification of genes that are involved in various diseases; advanced techniques The Daniel Sieff Research Institute, as the Weizmann for transplanting tissues; and the creation of a nanobiologi- Institute was originally called, was founded in 1934 by cal computer that may, in the future, be able to act directly Israel and Rebecca Sieff of the U.K., in memory of their inside the body to identify disease and eliminate it. son. The driving force behind its establishment was the Institute’s first president, Dr. Chaim Weizmann, a Today, the Institute is a leading force in advancing sci- noted chemist who headed the Zionist movement for ence education in all parts of society. Programs offered years and later became the first president of Israel. -

Israel and the Occupied Territories 2015 Human Rights Report

ISRAEL 2015 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Israel is a multiparty parliamentary democracy. Although it has no constitution, the parliament, the unicameral 120-member Knesset, has enacted a series of “Basic Laws” that enumerate fundamental rights. Certain fundamental laws, orders, and regulations legally depend on the existence of a “state of emergency,” which has been in effect since 1948. Under the Basic Laws, the Knesset has the power to dissolve the government and mandate elections. The nationwide Knesset elections in March, considered free and fair, resulted in a coalition government led by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security services. (An annex to this report covers human rights in the occupied territories. This report deals with human rights in Israel and the Israeli- occupied Golan Heights.) During the year according to Israeli Security Agency (ISA, also known as Shabak) statistics, Palestinians committed 47 terror attacks (including stabbings, assaults, shootings, projectile and rocket attacks, and attacks by improvised explosive devices (IED) within the Green Line that led to the deaths of five Israelis and one Eritrean, and two stabbing terror attacks committed by Jewish Israelis within the Green Line and not including Jerusalem. According to the ISA, Hamas, Hezbollah, and other militant groups fired 22 rockets into Israel and in 11 other incidents either planted IEDs or carried out shooting or projectile attacks into Israel and the Golan Heights. Further -

West Nile Virus (WNV) Activity in Humans and Mosquitos

West Nile virus (WNV) activity in humans and mosquitos Updated for 28/11/2016 In the following report, a human case patient who is defined as "suspected" refers to a patient whose lab test results indicate a possibility of infection with WNV, and a human case patient who is defined as "confirmed" refers to a patient whose lab test results show a definite infection with WNV. The final definition status of a patient who initially was diagnosed as "suspected" may be changed to "confirmed" due to additional lab test results that were obtained over time. Cumulative numbers of human case patients and mosquitos positive for WNV by location: Until the 28/11/2016, human cases with WNF have been identified in 54 localities and WNV infected mosquitos were found in 6 localities. אגף לאפידמיולוגיה Division of Epidemiology משרד הבריאות Ministry of Health ת.ד.1176 ירושלים P.O.B 1176 Jerusalem [email protected] [email protected] טל: 02-5080522 פקס: Tel: 972-2-5080522 Fax: 972-2-5655950 02-5655950 Table showing WNV in human by place of residency: Date sample Diagnostic status Locality No. Locality Health district received in lab according to lab 1 Or Yehuda 31/05/2016 Suspected Tel Aviv Or Yehuda 02/06/2016 Suspected Tel Aviv 2 Or Aqiva 17/07/2016 Suspected Hadera 3 Ashdod 19/09/2016 Suspected Ashqelon Ashdod 27/09/2016 Confirmed Ashqelon 4 Ashqelon 29/08/2016 Suspected Ashqelon Ashqelon 05/09/2016 Confirmed Ashqelon Ashqelon 08/09/2016 Confirmed Ashqelon Ashqelon 13/09/2016 Confirmed Ashqelon Ashqelon 22/09/2016 Confirmed Ashqelon -

Three Conquests of Canaan

ÅA Wars in the Middle East are almost an every day part of Eero Junkkaala:of Three Canaan Conquests our lives, and undeniably the history of war in this area is very long indeed. This study examines three such wars, all of which were directed against the Land of Canaan. Two campaigns were conducted by Egyptian Pharaohs and one by the Israelites. The question considered being Eero Junkkaala whether or not these wars really took place. This study gives one methodological viewpoint to answer this ques- tion. The author studies the archaeology of all the geo- Three Conquests of Canaan graphical sites mentioned in the lists of Thutmosis III and A Comparative Study of Two Egyptian Military Campaigns and Shishak and compares them with the cities mentioned in Joshua 10-12 in the Light of Recent Archaeological Evidence the Conquest stories in the Book of Joshua. Altogether 116 sites were studied, and the com- parison between the texts and the archaeological results offered a possibility of establishing whether the cities mentioned, in the sources in question, were inhabited, and, furthermore, might have been destroyed during the time of the Pharaohs and the biblical settlement pe- riod. Despite the nature of the two written sources being so very different it was possible to make a comparative study. This study gives a fresh view on the fierce discus- sion concerning the emergence of the Israelites. It also challenges both Egyptological and biblical studies to use the written texts and the archaeological material togeth- er so that they are not so separated from each other, as is often the case. -

Memories for a Lifetime

INCLUDED HIGHLIGHTS • An Intimate Group Experience with the Finest Guides and Drivers- Israel’s BEST! • Travel on Luxury Motor Coaches Proudly recognized as one of Israel’s Leading Tour Operators since 1980 • Exciting Comprehensive Itinerary covering the whole country from North to South MEMORIES FOR A LIFETIME Wendy Morse • Deluxe 5 Star Hotels in great locations • ALL spectacular buffet breakfasts • ALL dinners (except two) • Wonderful Evening Entertainment • ALL Entrance Fees – no waiting- the Margaret Morse Group with VIP access • Special Shehecheyanu Welcome in Jerusalem • Group Photograph in Jerusalem Robyn Morse O’Keefe Michael Morse • Gratuities to maids, waiters, and porters throughout the tour • PLUS WONDERFUL SURPRISE EXTRAS ALWAYS !!!! Margaret Morse Tours, Inc. 900 N. Federal Highway, Suite 206 No One Does Israel Better! No One. Hallandale Beach, FL 33009 TEL. 954.458.2021 • FAX. 954.455.9144 Toll Free 1.800.327.3191 Our Tour Guides email: [email protected] For more info visit our Website: www.margaretmorsetours.com Haifa Jerusalem Massada Eilat Tel Aviv www.margaretmorsetours.com 800.327.3191 Margaret Morse Tours, Inc. act only as Agents for various companies, owners, or contractors providing means of transportation, accommodation and other services. All exchange orders, coupons and tickets are issued subject to the terms and conditions under which such means of transportation; accommodations and other services are provided. The issuance and acceptance of such tickets shall be deemed to be consent to the further conditions that Margaret Morse Tours, Inc. shall not be in any way liable for injury, damage, loss, accident, delay or irregularity which may be occasioned either by defect or irregularity in any vehicle, or through the acts or defaults of any company or person engaged in conveying the passengers of any hotel proprietor, personnel or servant otherwise in connection therewith. -

Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict

Israeli Security Agency [logo] Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict September 2000 - September 2007 L_C089061 Table of Contents: Foreword...........................................................................................................................1 Suicide Terrorists - Personal Characteristics................................................................2 Suicide Terrorists Over 7 Years of Conflict - Geographical Data...............................3 Suicide Attacks since the Beginning of the Conflict.....................................................5 L_C089062 Israeli Security Agency [logo] Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict Foreword Since September 2000, the State of Israel has been in a violent and ongoing conflict with the Palestinians, in which the Palestinian side, including its various organizations, has carried out attacks against Israeli citizens and residents. During this period, over 27,000 attacks against Israeli citizens and residents have been recorded, and over 1000 Israeli citizens and residents have lost their lives in these attacks. Out of these, 155 (May 2007) attacks were suicide bombings, carried out against Israeli targets by 178 (August 2007) suicide terrorists (male and female). (It should be noted that from 1993 up to the beginning of the conflict in September 2000, 38 suicide bombings were carried out by 43 suicide terrorists). Despite the fact that suicide bombings constitute 0.6% of all attacks carried out against Israel since the beginning of the conflict, the number of fatalities in these attacks is around half of the total number of fatalities, making suicide bombings the most deadly attacks. From the beginning of the conflict up to August 2007, there have been 549 fatalities and 3717 casualties as a result of 155 suicide bombings. Over the years, suicide bombing terrorism has become the Palestinians’ leading weapon, while initially bearing an ideological nature in claiming legitimate opposition to the occupation. -

Excluded, for God's Sake: Gender Segregation and the Exclusion of Women in Public Space in Israel

Excluded, For God’s Sake: Gender Segregation and the Exclusion of Women in Public Space in Israel המרכז הרפורמי לדת ומדינה -לוגו ללא מספר. Third Annual Report – December 2013 Israel Religious Action Center Israel Movement for Reform and Progressive Judaism Excluded, For God’s Sake: Gender Segregation and the Exclusion of Women in Public Space in Israel Third Annual Report – December 2013 Written by: Attorney Ruth Carmi, Attorney Ricky Shapira-Rosenberg Consultation: Attorney Einat Hurwitz, Attorney Orly Erez-Lahovsky English translation: Shaul Vardi Cover photo: Tomer Appelbaum, Haaretz, September 29, 2010 – © Haaretz Newspaper Ltd. © 2014 Israel Religious Action Center, Israel Movement for Reform and Progressive Judaism Israel Religious Action Center 13 King David St., P.O.B. 31936, Jerusalem 91319 Telephone: 02-6203323 | Fax: 03-6256260 www.irac.org | [email protected] Acknowledgement In loving memory of Dick England z"l, Sherry Levy-Reiner z"l, and Carole Chaiken z"l. May their memories be blessed. With special thanks to Loni Rush for her contribution to this report IRAC's work against gender segregation and the exclusion of women is made possible by the support of the following people and organizations: Kathryn Ames Foundation Claudia Bach Philip and Muriel Berman Foundation Bildstein Memorial Fund Jacob and Hilda Blaustein Foundation Inc. Donald and Carole Chaiken Foundation Isabel Dunst Naomi and Nehemiah Cohen Foundation Eugene J. Eder Charitable Foundation John and Noeleen Cohen Richard and Lois England Family Jay and Shoshana Dweck Foundation Foundation Lewis Eigen and Ramona Arnett Edith Everett Finchley Reform Synagogue, London Jim and Sue Klau Gold Family Foundation FJC- A Foundation of Philanthropic Funds Vicki and John Goldwyn Mark and Peachy Levy Robert Goodman & Jayne Lipman Joseph and Harvey Meyerhoff Family Richard and Lois Gunther Family Foundation Charitable Funds Richard and Barbara Harrison Yocheved Mintz (Dr.