Shorting Ethos? Aristotelian Ethos in the Context of Corporate Reputation, Persuasion and Shared Values

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aristotelian Appeals: Logos, Ethos, and Pathos

Aristotelian Appeals: Logos, Ethos, and Pathos Whenever you read an argument you must ask yourself, “Is this persuasive? If so, why? And to whom?” There are many ways to appeal to an audience. Among them are appealing to logos, ethos, and pathos. These appeals are identifiable in almost all arguments. To Appeal to LOGOS To Develop or Appeal to ETHOS To Appeal to PATHOS (logic, reasoning) (character, ethics) (emotion) : the argument itself; the reasoning the : how an author builds credibility & : words or passages an author uses to activate author uses; logical evidence trustworthiness emotions Types of LOGOS Appeals Ways to Develop ETHOS Types of PATHOS Appeals Theories / scientific facts Author’s profession / Emotionally loaded language Indicated meanings or background Vivid descriptions reasons (because…) Author’s publication Emotional examples Literal or historical analogies Appearing sincere, fair minded, Anecdotes, testimonies, or narratives Definitions knowledgeable about emotional experiences or events Factual data & statistics Conceding to opposition where Figurative language Quotations appropriate Emotional tone (humor, sarcasm, Citations from experts & Morally / ethically likeable disappointment, excitement, etc.) authorities Appropriate language for Informed opinions audience and subject Examples (real life examples) Appropriate vocabulary Personal anecdotes Correct grammar Professional format Effect on Audience Effect on Audience Effect on Audience Evokes a cognitive, rational response. Helps reader -

Rhetorical Appeals (Or Modes of Persuasion)

Rhetorical Appeals (or modes of persuasion) The rhetorical appeals were introduced by Aristotle (382-322 B.C.) in his text Rhetoric: Of the modes of persuasion furnished by the spoken word there are three kinds. [...] Persuasion is achieved by the speaker's personal character when the speech is so spoken as to make us think him credible. [...] Secondly, persuasion may come through the hearers, when the speech stirs their emotions. [...] Thirdly, persuasion is effected through the speech itself when we have proved a truth or an apparent truth by means of the persuasive arguments suitable to the case in question. Three Appeals Ethos Proof in the Persuader (ethical appeal) Arguments based on increasing the writer or the paper’s credibility and authority o How knowledgeable and prepared is the writer Types o Referring to your skills or titles o Research from reliable sources o Personal Experience and/or interest in the topic o References to credible individuals (quotes and paraphrase) Pros: enhances writer; makes other research look better; adds new voices Cons: bias may influence; lack of expertise shows; doesn’t work by itself Pathos (the pathetic) Emotional appeals Arguments based on reactions from readers o Connects argument to reader values Types o Vivid Language (metaphor, simile, word choice) o Examples/Stories o Imagery (ex: animal rights newsletters or arguments about abortion) Pros: highly persuasive; involves readers; can lead to quick action Cons: over-emotion; easier to disprove; readers may have negative reaction Logos Logical appeals Appeals and arguments that refer to factual proof, evidence, and/or reason Types o Statistics o Examples o Cause and Effect o Syllogism (A + B = C) Pros: hard to disprove; highly persuasive; makes writer look more prepared (enhances ethos) Cons: Numbers can lie or confuse; may not intrigue reader (lack of emotion); may be inaccurate Sources to consult: Lunsford, Andrea. -

Ethos, Pathos, and Logos Ethos

RHETORICAL APPEALS: ETHOS, PATHOS, AND LOGOS ETHOS Appeal to authority/speaker credibility/common values • Speaker uses ethos to convince audience of his/her credibility/expertise and/or moral character. • Argument is proven believable/valid by using celebrities/name dropping, referencing resume/personal experience (including title), establishing trust, and citing research. • Ethos = Greek for “character” • “Ethics” - derived from ethos ETHOS EXAMPLE PATHOS Appeal to emotion/fear/human suffering • Speaker uses pathos to invoke sympathy and cause audience to make decisions based on feelings , uses collective language (“we”, “our”), direct address (“you”), repetition, extreme/dramatic diction, sentimental/relatable examples/ anecdotes/imagery (babies, puppies, 9/11). • Pathos = Greek for “suffering” and “experience” • “Empathy” and “Pathetic” - derived from pathos PATHOS EXAMPLE LOGOS Appeal to logic • Speaker uses logos to persuade through reason/logic by presenting facts, statistics, historical and literal analogies (if…then) • Logos = Greek for “word” • True definition: “the word or that by which the inward though is expressed” • “Logic” is derived from logos LOGOS EXAMPLE ETHOS, PATHOS, OR LOGOS? Examine rhetorical appeals in following advertisements. • Analyze visual aspects (color, shading, detail, lines, lighting, position) • Determine Speaker, Occasion, Audience, Purpose, Subject, and Tone. • Identify appeals to sense of authority, emotion, and/or logic ETHOS, PATHOS, OR LOGOS? ETHOS, PATHOS, OR LOGOS? ETHOS, PATHOS, OR LOGOS? ETHOS, PATHOS, OR LOGOS? E2H OUTCOME D PRACTICE: VISUAL RHETORIC • Find an advertisement with a clear appeal to ethos, logos, pathos. • Bring to class Friday with written reflection: • Claim what appeal is prominent. Include textual evidence. What DIDLS, etc. in the visual convey that appeal? • Will share and discuss. -

Teacher's Edition

TEACHER’SClassical SubjectsEDITION Creatively Taught™ Rhetoric BOOK 1: PRINCIPLESAlive!Alive! OF PERSUASION PERSUASIVE SPEECH AND WRITING IN THE TRADITION OF ARISTOTLE Alyssan Barnes, PhD Dedication: To Annie, June, and Zoe Rhetoric RhetoricAlive! Book Alive! 1: PrinciplesBook 1: Principles of Persuasion of Persuasion Teacher’s Edition © Classical Academic Press, 2016 Version 1.0 ISBN: 978-1-60051-300-8978-1-60051-301-5 All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of Classical Academic Press. Classical Academic Press 2151 Market Street Camp Hill, PA 17011 www.ClassicalAcademicPress.com Content editors: Christopher Perrin, PhD; Joelle Hodge; and Stephen Barnes Editor: Sharon Berger Illustrator: David Gustafson Book designer: Robert Baddorf PGP.07.16 Table of Contents List of Figures, Tables, and Chart .................................................................................................................. vii Foreword ........................................................................................................................................................ix Acknowledgments ...........................................................................................................................................xi Note to Student ............................................................................................................................................ xii OverviewNote to Teacher -

![Greek Color Theory and the Four Elements [Full Text, Not Including Figures] J.L](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6957/greek-color-theory-and-the-four-elements-full-text-not-including-figures-j-l-1306957.webp)

Greek Color Theory and the Four Elements [Full Text, Not Including Figures] J.L

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Greek Color Theory and the Four Elements Art July 2000 Greek Color Theory and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures] J.L. Benson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgc Benson, J.L., "Greek Color Theory and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures]" (2000). Greek Color Theory and the Four Elements. 1. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgc/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Greek Color Theory and the Four Elements by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cover design by Jeff Belizaire ABOUT THIS BOOK Why does earlier Greek painting (Archaic/Classical) seem so clear and—deceptively— simple while the latest painting (Hellenistic/Graeco-Roman) is so much more complex but also familiar to us? Is there a single, coherent explanation that will cover this remarkable range? What can we recover from ancient documents and practices that can objectively be called “Greek color theory”? Present day historians of ancient art consistently conceive of color in terms of triads: red, yellow, blue or, less often, red, green, blue. This habitude derives ultimately from the color wheel invented by J.W. Goethe some two centuries ago. So familiar and useful is his system that it is only natural to judge the color orientation of the Greeks on its basis. To do so, however, assumes, consciously or not, that the color understanding of our age is the definitive paradigm for that subject. -

Leader Character, Ethos, and Virtue: Individual and Collective Considerations Sean T

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln US Army Research U.S. Department of Defense 2011 Leader character, ethos, and virtue: Individual and collective considerations Sean T. Hannah West Point-United States Military Academy, [email protected] Bruce Avolio University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usarmyresearch Hannah, Sean T. and Avolio, Bruce, "Leader character, ethos, and virtue: Individual and collective considerations" (2011). US Army Research. 263. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usarmyresearch/263 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Defense at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in US Army Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The Leadership Quarterly 22 (2011) 989–994 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect The Leadership Quarterly journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/leaqua Discussion Leader character, ethos, and virtue: Individual and collective considerations Sean T. Hannah a,⁎, Bruce J. Avolio b,1 a Center for the Army Profession and Ethic, West Point-United States Military Academy, 646 Swift Road, West Point, NY 10996, USA b Center for Leadership & Strategic Thinking, University of Washington, Management and Organization Department, Box 353200, Seattle, WA 98195-3200, USA article info abstract Available online 19 August 2011 We advance the discussion that each leader has a moral component that can be defined as character that is distinct from values, personality, and other similar constructs. We seek to clarify what underpins forms of character-based leadership and exemplary leader behaviors. -

What the Hellenism: Did Christianity Cause a Decline of Th Hellenism in 4 -Century Alexandria?

What the Hellenism: Did Christianity cause a decline of th Hellenism in 4 -century Alexandria? Classics Dissertation Exam Number B051946 B051946 2 Contents List of Figures ............................................................................................................................ 2 List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................. 2 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 3 Problems with Evidence ......................................................................................................... 8 Pagan Topography and Demography......................................................................................... 9 Christian Topography .............................................................................................................. 19 Civic Power Structures ............................................................................................................ 29 Intellectualism .......................................................................................................................... 38 Conclusion ............................................................................................................................... 47 Bibliography of Primary Sources in Translation ..................................................................... 52 Figure Bibliography ................................................................................................................ -

Understanding and Using Logos, Ethos, and Pathos

School of Liberal Arts University Writing Center “Because writers need readers” Cavanaugh Hall 427 University Library 2125 (317)274-2049 (317)278-8171 www.iupui.edu/~uwc The Rhetorical Triangle: Understanding and Using Logos, Ethos, and Pathos Logos, ethos, and pathos are important components of all writing, whether we are aware of them or not. By learning to recognize logos, ethos, and pathos in the writing of others and in our own, we can create texts that appeal to readers on many different levels. This handout provides a brief overview of what logos, ethos, and pathos are and offers guiding questions for recognizing and incorporating these appeals. Aristotle taught that a speaker’s ability to persuade an audience is based on how well the speaker appeals to that audience in three different areas: logos, ethos, and pathos. Considered together, these appeals form what later rhetoricians have called the rhetorical triangle. Logos appeals to reason. Logos can also be thought of as the text of the argument, as well as how well a writer has argued his/her point. Ethos appeals to the writer’s character. Ethos can also be thought of as the role of the writer in the argument, and how credible his/her argument is. Pathos appeals to the emotions and the sympathetic imagination, as well as to beliefs and values. Pathos can also be thought of as the role of the audience in the argument. LOGOS (Reason/Text) ETHOS PATHOS (Credibility/Writer) (Values, Beliefs/Audience) The rhetorical triangle is typically represented by an equilateral triangle, suggesting that logos, ethos, and pathos should be balanced within a text. -

The Demiurge of Words by Benjamin Syn

UCCS|Undergraduate Research Journal|12.1 The Demiurge of Words by Benjamin Syn Traditional rhetorical theory posits that each of the three Aristotelian appeals, or pisteis, exist in three separate locations: pathos within the audience, logos within the message, and ethos within the rhetor; however, just as logos resides within the text itself, pathos too is crafted by the text. As such, logic and organization are within the words themselves, and so is any emotional reaction elicited by the audience. Therefore, the rhetorical energy that powers the logos also fuels the pathos. While these two appeals are within the text, I am going to forward that arête and ethos equally exist within a text and consequently are wholly constructed by the text itself—even perhaps despite the rhetor. In addition, I am going to propose that the seemingly fixed and universal concept of history is also crafted within a text. Finally, I will highlight that all these attributes are rhetorical and that rhetoric itself is magic. Throughout history, there has been this seemingly omnipresent binary between what is innate and what is learned. For example, Homer in the eighth century BC advocated that legendary individuals, like Achilles, were born with arête, and the council who ruled Athens at the time of Solon in the sixth century BC advocated their right to rule by their intrinsic greatness, the arête of their birth (Williams 24, 64). Twentieth-century classicist Werner Jaeger explains in his The Ideals of Greek Culture that “the root of the word [arête] is the same as aristos, the word which shows superlative ability and superiority, and aristos was constantly used in the plural to denote the nobility” (5). -

Phronesis As the Sense of the Event

www.ssoar.info Phronesis as the Sense of the Event Kirkeby, Ole Fogh Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: Rainer Hampp Verlag Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kirkeby, O. F. (2009). Phronesis as the Sense of the Event. International Journal of Action Research, 5(1), 68-113. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-412808 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder conditions of use. anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. -

Discussion Paper No. 7 Religion and Populism: Reflections On

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by LSE Research Online Discussion Paper No. 7 Religion and Populism: Reflections on the ‘politicised’ discourse of the Greek Church Yannis Stavrakakis May 2002 The Hellenic Observatory The European Institute London School of Economics & Political Science Table of Contents Introduction............................................................................................8 A. Clearing the Ground: A Comment on Politicisation.....................13 1. Secularisation and politicisation................................................17 2. Burdens of history......................................................................22 B. The discourse of the Greek Church: Christodoulos’ populism?...27 C. To Conclude: Directions for Future Research...............................35 1. The emergence of populist discourses and the question of a populist desire........................................................................ 36 2. Tradition v. modernisation: from cultural dualism to split identity?……………………………………………………37 WORKS CITED ..................................................................................43 Acknowledgments It has been pointed out that it is always impolite to argue about religion or politics with strangers and dangerous to do so with friends. I am probably doing both in this paper and would never find the courage to embark in such a task without the support and valuable comments of colleagues who read earlier drafts of this text. In particular, I would -

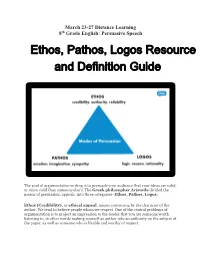

Ethos, Pathos, Logos Resource and Definition Guide

March 23-27 Distance Learning 8th Grade English: Persuasive Speech Ethos, Pathos, Logos Resource and Definition Guide The goal of argumentative writing is to persuade your audience that your ideas are valid, or more valid than someone else’s. The Greek philosopher Aristotle divided the means of persuasion, appeals, into three categories–Ethos, Pathos, Logos. Ethos (Credibility), or ethical appeal, means convincing by the character of the author. We tend to believe people whom we respect. One of the central problems of argumentation is to project an impression to the reader that you are someone worth listening to, in other words making yourself as author into an authority on the subject of the paper, as well as someone who is likable and worthy of respect. Pathos (Emotional) means persuading by appealing to the reader’s emotions. We can look at texts ranging from classic essays to contemporary advertisements to see how pathos, emotional appeals, are used to persuade. Language choice affects the audience’s emotional response, and emotional appeal can effectively be used to enhance an argument. Logos (Logical) means persuading by the use of reasoning. This will be the most important technique we will study, and Aristotle’s favorite. We’ll look at deductive and inductive reasoning, and discuss what makes an effective, persuasive reason to back up your claims. Giving reasons is the heart of argumentation, and cannot be emphasized enough. We’ll study the types of support you can use to substantiate your thesis, and look at some of the common logical fallacies, in order to avoid them in your writing.