Thomas Annan of Glasgow Pioneer of the Documentary Photograph

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Death of Captain Cook in Theatre 224

The Many Deaths of Captain Cook A Study in Metropolitan Mass Culture, 1780-1810 Ruth Scobie PhD University of York Department of English April 2013 i Ruth Scobie The Many Deaths of Captain Cook Abstract This thesis traces metropolitan representations, between 1780 and 1810, of the violent death of Captain James Cook at Kealakekua Bay in Hawaii. It takes an interdisciplinary approach to these representations, in order to show how the interlinked texts of a nascent commercial culture initiated the creation of a colonial character, identified by Epeli Hau’ofa as the looming “ghost of Captain Cook.” The introduction sets out the circumstances of Cook’s death and existing metropolitan reputation in 1779. It situates the figure of Cook within contemporary mechanisms of ‘celebrity,’ related to notions of mass metropolitan culture. It argues that previous accounts of Cook’s fame have tended to overemphasise the immediacy and unanimity with which the dead Cook was adopted as an imperialist hero; with the result that the role of the scene within colonialist histories can appear inevitable, even natural. In response, I show that a contested mythology around Cook’s death was gradually constructed over the three decades after the incident took place, and was the contingent product of a range of texts, places, events, and individuals. The first section examines responses to the news of Cook’s death in January 1780, focusing on the way that the story was mediated by, first, its status as ‘news,’ created by newspapers; and second, the effects on Londoners of the Gordon riots in June of the same year. -

Classical Nakedness in British Sculpture and Historical Painting 1798-1840 Cora Hatshepsut Gilroy-Ware Ph.D Univ

MARMOREALITIES: CLASSICAL NAKEDNESS IN BRITISH SCULPTURE AND HISTORICAL PAINTING 1798-1840 CORA HATSHEPSUT GILROY-WARE PH.D UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART SEPTEMBER 2013 ABSTRACT Exploring the fortunes of naked Graeco-Roman corporealities in British art achieved between 1798 and 1840, this study looks at the ideal body’s evolution from a site of ideological significance to a form designed consciously to evade political meaning. While the ways in which the incorporation of antiquity into the French Revolutionary project forged a new kind of investment in the classical world have been well-documented, the drastic effects of the Revolution in terms of this particular cultural formation have remained largely unexamined in the context of British sculpture and historical painting. By 1820, a reaction against ideal forms and their ubiquitous presence during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wartime becomes commonplace in British cultural criticism. Taking shape in a series of chronological case-studies each centring on some of the nation’s most conspicuous artists during the period, this thesis navigates the causes and effects of this backlash, beginning with a state-funded marble monument to a fallen naval captain produced in 1798-1803 by the actively radical sculptor Thomas Banks. The next four chapters focus on distinct manifestations of classical nakedness by Benjamin West, Benjamin Robert Haydon, Thomas Stothard together with Richard Westall, and Henry Howard together with John Gibson and Richard James Wyatt, mapping what I identify as -

Annual Report 2018–2019 Artmuseum.Princeton.Edu

Image Credits Kristina Giasi 3, 13–15, 20, 23–26, 28, 31–38, 40, 45, 48–50, 77–81, 83–86, 88, 90–95, 97, 99 Emile Askey Cover, 1, 2, 5–8, 39, 41, 42, 44, 60, 62, 63, 65–67, 72 Lauren Larsen 11, 16, 22 Alan Huo 17 Ans Narwaz 18, 19, 89 Intersection 21 Greg Heins 29 Jeffrey Evans4, 10, 43, 47, 51 (detail), 53–57, 59, 61, 69, 73, 75 Ralph Koch 52 Christopher Gardner 58 James Prinz Photography 76 Cara Bramson 82, 87 Laura Pedrick 96, 98 Bruce M. White 74 Martin Senn 71 2 Keith Haring, American, 1958–1990. Dog, 1983. Enamel paint on incised wood. The Schorr Family Collection / © The Keith Haring Foundation 4 Frank Stella, American, born 1936. Had Gadya: Front Cover, 1984. Hand-coloring and hand-cut collage with lithograph, linocut, and screenprint. Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960 / © 2017 Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 12 Paul Wyse, Canadian, born United States, born 1970, after a photograph by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, American, born 1952. Toni Morrison (aka Chloe Anthony Wofford), 2017. Oil on canvas. Princeton University / © Paul Wyse 43 Sally Mann, American, born 1951. Under Blueberry Hill, 1991. Gelatin silver print. Museum purchase, Philip F. Maritz, Class of 1983, Photography Acquisitions Fund 2016-46 / © Sally Mann, Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery © Helen Frankenthaler Foundation 9, 46, 68, 70 © Taiye Idahor 47 © Titus Kaphar 58 © The Estate of Diane Arbus LLC 59 © Jeff Whetstone 61 © Vesna Pavlovic´ 62 © David Hockney 64 © The Henry Moore Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 65 © Mary Lee Bendolph / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York 67 © Susan Point 69 © 1973 Charles White Archive 71 © Zilia Sánchez 73 The paper is Opus 100 lb. -

E-News Winter 2019/2020

Winter e-newsletter December 2019 Photos Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year! INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Contributions to our newsletters Dates for your Diary & Winter Workparties....2 Borage - Painted Lady foodplant…11-12 are always welcome. Scottish Entomological Gathering 2020 .......3-4 Lunar Yellow Underwing…………….13 Please use the contact details Obituary - David Barbour…………..………….5 Chequered Skipper Survey 2020…..14 below to get in touch! The Bog Squad…………………………………6 If you do not wish to receive our Helping Hands for Butterflies………………….7 newsletter in the future, simply Munching Caterpillars in Scotland………..…..8 reply to this message with the Books for Sale………………………...………..9 word ’unsubscribe’ in the title - thank you. RIC Project Officer - Job Vacancy……………9 Coul Links Update……………………………..10 VC Moth Recorder required for Caithness….10 Contact Details: Butterfly Conservation Scotland t: 01786 447753 Balallan House e: [email protected] Allan Park w: www.butterfly-conservation.org/scotland Stirling FK8 2QG Dates for your Diary Scottish Recorders’ Gathering - Saturday, 14th March 2020 For everyone interested in recording butterflies and moths, our Scottish Recorders’ Gathering will be held at the Battleby Conference Centre, by Perth on Saturday, 14th March 2020. It is an opportunity to meet up with others, hear all the latest butterfly and moth news and gear up for the season to come! All welcome - more details will follow in the New Year! Highland Branch AGM - Saturday, 18th April 2020 Our Highlands & Island Branch will be holding their AGM on Saturday, 18th April in a new venue, Green Drive Hall, 36 Green Drive, Inverness, IV2 4EU. More details will follow on the website in due course. -

Project #3: Inspired By… - Description Critique Date - 3/29/19 (Fri)

Project #3: Inspired by… - Description Critique Date - 3/29/19 (Fri) "The world is filled to suffocating. Man has placed his token on every stone. Every word, every image, is leased and mortgaged. We know that a picture is but a space in which a variety of images, none of them original, blend and clash." – Sherrie Levine Conceptual Requirements: In this project, you will do your best to interpret the style of a particular photographer who interests you. You will research them as well as their work in order to make photographs that have a signature aesthetic or approach that is specific to them, and also contribute your ideas. Technical Requirements: 1. Start with the list on the back of this page (the Project Description sheet), and start web searches for these photographers. All the ones listed are masters in their own right and a good starting point for you to begin your search. Select one and confirm your choice with me by the due date (see the syllabus). 2. After choosing a photographer, go on the web and to the library to check out books on them, read interviews, and look at every image you can that is made by them. Learn as much as you can and take notes on your sources. 3. Type your name, date, and “Project 3: Inspired by...” at the top of a Letter sized page. Then write a 2 page research paper on your chosen photographer. Be sure to include information such as where and when they were born, where it is that they did their work, what kind of camera and film formats they used, their own personal history, etc. -

Fishing Permits Information

Fishing permit retailers in the National Park 1 River Fillan 7 Loch Daine Strathfillan Wigwams Angling Active, Stirling 01838 400251 01786 430400 www.anglingactive.co.uk 2 Loch Dochart James Bayne, Callander Portnellan Lodges 01877 330218 01838 300284 www.fishinginthetrossachs.co.uk www.portnellan.com Loch Dochart Estate 8 Loch Voil 01838 300315 Angling Active, Stirling www.lochdochart.co. uk 01786 430400 www.anglingactive.co.uk 3 Loch lubhair James Bayne, Callander Auchlyne & Suie Estate 01877 330218 01567 820487 Strathyre Village Shop www.auchlyne.co.uk 01877 384275 Loch Dochart Estate Angling Active, Stirling 01838 300315 01786 430400 www.lochdochart.co. uk www.anglingactive.co.uk News First, Killin 01567 820362 9 River Balvaig www.auchlyne.co.uk James Bayne, Callander Auchlyne & Suie Estate 01877 330218 01567 820487 www.fishinginthetrossachs.co.uk www.auchlyne.co.uk Forestry Commission, Aberfoyle 4 River Dochart 01877 382383 Aberfoyle Post Office Glen Dochart Caravan Park 01877 382231 01567 820637 Loch Dochart Estate 10 Loch Lubnaig 01838 300315 Forestry Commission, Aberfoyle www.lochdochart.co. uk 01877 382383 Suie Lodge Hotel Strathyre Village Shop 01567 820040 01877 384275 5 River Lochay 11 River Leny News First, Killin James Bayne, Callander 01567 820362 01877 330218 Drummond Estates www.fishinginthetrossachs.co.uk 01567 830400 Stirling Council Fisheries www.drummondtroutfarm.co.uk 01786 442932 6 Loch Earn 12 River Teith Lochearnhead Village Store Angling Active, Stirling 01567 830214 01786 430400 St.Fillans Village Store www.anglingactive.co.uk -

Frommer's Scotland 8Th Edition

Scotland 8th Edition by Darwin Porter & Danforth Prince Here’s what the critics say about Frommer’s: “Amazingly easy to use. Very portable, very complete.” —Booklist “Detailed, accurate, and easy-to-read information for all price ranges.” —Glamour Magazine “Hotel information is close to encyclopedic.” —Des Moines Sunday Register “Frommer’s Guides have a way of giving you a real feel for a place.” —Knight Ridder Newspapers About the Authors Darwin Porter has covered Scotland since the beginning of his travel-writing career as author of Frommer’s England & Scotland. Since 1982, he has been joined in his efforts by Danforth Prince, formerly of the Paris Bureau of the New York Times. Together, they’ve written numerous best-selling Frommer’s guides—notably to England, France, and Italy. Published by: Wiley Publishing, Inc. 111 River St. Hoboken, NJ 07030-5744 Copyright © 2004 Wiley Publishing, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval sys- tem or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo- copying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978/750-8400, fax 978/646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for per- mission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, 317/572-3447, fax 317/572-4447, E-Mail: [email protected]. -

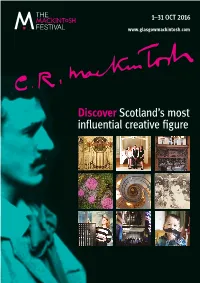

Discoverscotland's Most Influential

1–31 OCT 2016 www.glasgowmackintosh.com Discover Scotland’s most influential creative figure A Charles Rennie Mackintosh The Mackintosh Festival is organised 1868–1928. by members of Glasgow Mackintosh: Architect. Artist. Designer. Icon. Kelvingrove Art Gallery & Museum The work of the Scottish architect, designer Scotland Street School Museum and artist, Charles Rennie Mackintosh is today The Glasgow School of Art celebrated internationally. Mackintosh was one Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society of the most sophisticated exponents of the House for An Art Lover theory of the room as a work of art, and created The Hunterian distinctive furniture of great formal elegance. In The Hill House Glasgow, you will see the finest examples of his The Lighthouse buildings and interiors and examples of his creative The Glasgow Art Club collaborations with his wife, the accomplished Glasgow Museums Resource Centre (GMRC) artist and designer Margaret Macdonald. Mackintosh Queen’s Cross Special thanks to our partners: GBPT Doors Open Day Glasgow Women’s Library The Willow Tea Rooms The Glad Café Glasgow City Marketing Bureau Glasgow Restaurateurs Association Welcome to the fifth Mackintosh Festival Glasgow Mackintosh is delighted to present another month-long programme of over 40 arts and cultural events to celebrate the life of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Glasgow’s most famous architect, designer and artist. This year we are celebrating House – where you can celebrate installation of Kathy Hinde’s the 2016 Year of Innovation, their 20th birthday with kids -

Scottish Art: Then and Now

Scottish Art: Then and Now by Clarisse Godard-Desmarest “Ages of Wonder: Scotland’s Art 1540 to Now”, an exhibition presented in Edinburgh by the Royal Scottish Academy of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture tells the story of collecting Scottish art. Mixing historic and contemporary works, it reveals the role played by the Academy in championing the cause of visual arts in Scotland. Reviewed: Tom Normand, ed., Ages of Wonder: Scotland’s Art 1540 to Now Collected by the Royal Scottish Academy of Art and Architecture, Edinburgh, The Royal Scottish Academy, 2017, 248 p. The Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) and the National Galleries of Scotland (NGS) have collaborated to present a survey of collecting by the academy since its formation in 1826 as the Scottish Academy of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. Ages of Wonder: Scotland’s Art 1540 to Now (4 November 2017-7 January 2018) is curated by RSA President Arthur Watson, RSA Collections Curator Sandy Wood and Honorary Academician Tom Normand. It has spawned a catalogue as well as a volume of fourteen essays, both bearing the same title as the exhibition. The essay collection, edited by Tom Normand, includes chapters on the history of the RSA collections, the buildings on the Mound, artistic discourse in the nineteenth century, teaching at the academy, and Normand’s “James Guthrie and the Invention of the Modern Academy” (pp. 117–34), on the early, complex history of the RSA. Contributors include Duncan Macmillan, John Lowrey, William Brotherston, John Morrison, Helen Smailes, James Holloway, Joanna Soden, Alexander Moffat, Iain Gale, Sandy Wood, and Arthur Watson. -

Barrow-In-Furness, Cumbria

BBC VOICES RECORDINGS http://sounds.bl.uk Title: Barrow-in-Furness, Cumbria Shelfmark: C1190/11/01 Recording date: 2005 Speakers: Airaksinen, Ben, b. 1987 Helsinki; male; sixth-form student (father b. Finland, research scientist; mother b. Barrow-in-Furness) France, Jane, b. 1954 Barrow-in-Furness; female; unemployed (father b. Knotty Ash, shoemaker; mother b. Bootle, housewife) Andy, b. 1988 Barrow-in-Furness; male; sixth-form student (father b. Barrow-in-Furness, shop sales assistant; mother b. Harrow, dinner lady) Clare, b. 1988 Barrow-in-Furness; female; sixth-form student (father b. Barrow-in-Furness, farmer; mother b. Brentwood, Essex) Lucy, b. 1988 Leeds; female; sixth-form student (father b. Pudsey, farmer; mother b. Dewsbury, building and construction tutor; nursing home activities co-ordinator) Nathan, b. 1988 Barrow-in-Furness; male; sixth-form student (father b. Dalton-in-Furness, IT worker; mother b. Barrow-in-Furness) The interviewees (except Jane France) are sixth-form students at Barrow VI Form College. ELICITED LEXIS ○ see English Dialect Dictionary (1898-1905) ∆ see New Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English (2006) ◊ see Green’s Dictionary of Slang (2010) ♥ see Dictionary of Contemporary Slang (2014) ♦ see Urban Dictionary (online) ⌂ no previous source (with this sense) identified pleased chuffed; happy; made-up tired knackered unwell ill; touch under the weather; dicky; sick; poorly hot baking; boiling; scorching; warm cold freezing; chilly; Baltic◊ annoyed nowty∆; frustrated; pissed off; miffed; peeved -

Charles Rennie Mackintosh in Glasgow

Charles Rennie Mackintosh In Glasgow Travel This tour starts and finishes at the Hilton Grosvenor Hotel, Glasgow. 1-9 Grosvenor Terrace, Glasgow, G12 0TA Tel: 0141 339 8811 Please note that transport to the hotel is not included in the price of the tour. Transport If you are travelling by car: The Hilton Glasgow Grosvenor is located 5 minutes from the M8 motorway and 5 minutes’ walk from Hillhead subway station. The hotel is situated on the corner of the junction between Byres Road and Great Western Road. On arrival, directly after the hotel turn right, into the lane between the Hilton and Waitrose. Stop at the hotel entrance and get a car park ticket from reception. Finally, drive up the ramp of the Waitrose car park on the left, and keep on going until the top level, which is reserved for hotel guests and the residents of the adjoining flats. Parking is £10 per day, payable locally. If you are travelling by train: The nearest subway stop is Hillhead, which is about a 5 minute walk away on Byres Road. Glasgow Central Station is about 15 minutes by taxi to the hotel. Accommodation The Hilton Grosvenor Hotel The Hilton Grosvenor Hotel is a traditional four-star hotel in the vibrant West End area of the city centre. It is ideally situated in close proximity to the array of locations visited during your tour including the Hunterian Gallery and University. Bedrooms are equipped with all necessities to ensure a relaxing and enjoyable visit, including an en-suite bathroom with bath/shower, TV, telephone, Wi-Fi, hairdryer and complimentary tea/coffee making facilities. -

Century British Photography and the Case of Walter Benington by Robert William Crow

Reputations made and lost: the writing of histories of early twentieth- century British photography and the case of Walter Benington by Robert William Crow A thesis submitted to the University of Gloucestershire in accordance with the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Technology January 2015 Abstract Walter Benington (1872-1936) was a major British photographer, a member of the Linked Ring and a colleague of international figures such as F H Evans, Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen and Alvin Langdon Coburn. He was also a noted portrait photographer whose sitters included Albert Einstein, Dame Ellen Terry, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and many others. He is, however, rarely noted in current histories of photography. Beaumont Newhall’s 1937 exhibition Photography 1839-1937 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York is regarded by many respected critics as one of the foundation-stones of the writing of the history of photography. To establish photography as modern art, Newhall believed it was necessary to create a direct link between the master-works of the earliest photographers and the photographic work of his modernist contemporaries in the USA. He argued that any work which demonstrated intervention by the photographer such as the use of soft-focus lenses was a deviation from the direct path of photographic progress and must therefore be eliminated from the history of photography. A consequence of this was that he rejected much British photography as being “unphotographic” and dangerously irrelevant. Newhall’s writings inspired many other historians and have helped to perpetuate the neglect of an important period of British photography.