America's "Cinderella"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fairy Tale Females: What Three Disney Classics Tell Us About Women

FFAAIIRRYY TTAALLEE FFEEMMAALLEESS:: WHAT THREE DISNEY CLASSICS TELL US ABOUT WOMEN Spring 2002 Debbie Mead http://members.aol.com/_ht_a/ vltdisney?snow.html?mtbrand =AOL_US www.kstrom.net/isk/poca/pocahont .html www_unix.oit.umass.edu/~juls tar/Cinderella/disney.html Spring 2002 HCOM 475 CAPSTONE Instructor: Dr. Paul Fotsch Advisor: Professor Frances Payne Adler FAIRY TALE FEMALES: WHAT THREE DISNEY CLASSICS TELL US ABOUT WOMEN Debbie Mead DEDICATION To: Joel, whose arrival made the need for critical viewing of media products more crucial, Oliver, who reminded me to be ever vigilant when, after viewing a classic Christmas video from my youth, said, “Way to show me stereotypes, Mom!” Larry, who is not a Prince, but is better—a Partner. Thank you for your support, tolerance, and love. TABLE OF CONTENTS Once Upon a Time --------------------------------------------1 The Origin of Fairy Tales ---------------------------------------1 Fairy Tale/Legend versus Disney Story SNOW WHITE ---------------------------------------------2 CINDERELLA ----------------------------------------------5 POCAHONTAS -------------------------------------------6 Film Release Dates and Analysis of Historical Influence Snow White ----------------------------------------------8 Cinderella -----------------------------------------------9 Pocahontas --------------------------------------------12 Messages Beauty --------------------------------------------------13 Relationships with other women ----------------------19 Relationships with men --------------------------------21 -

Damsel in Distress Or Princess in Power? Traditional Masculinity and Femininity in Young Adult Novelizations of Cinderella and the Effects on Agency

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2020-12-09 Damsel in Distress or Princess in Power? Traditional Masculinity and Femininity in Young Adult Novelizations of Cinderella and the Effects on Agency Rylee Carling Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Education Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Carling, Rylee, "Damsel in Distress or Princess in Power? Traditional Masculinity and Femininity in Young Adult Novelizations of Cinderella and the Effects on Agency" (2020). Theses and Dissertations. 8758. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/8758 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Damsel in Distress or Princess in Power? Traditional Masculinity and Femininity in Young Adult Novelizations of Cinderella and the Effects on Agency Rylee Carling A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Paul Ricks, Chair Terrell Young Dawan Coombs Stefinee Pinnegar Department of Teacher Education Brigham Young University Copyright © 2020 Rylee Carling All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Damsel in Distress or Princess in Power? Traditional Masculinity and Femininity in Young Adult Novelizations of Cinderella and the Effects on Agency Rylee Carling Department of Teacher Education, BYU Master of Arts Retellings of classic fairy tales have become increasingly popular in the past decade, but little research has been done on the novelizations written for a young adult (YA) audience. -

Princess Stories Easy Please Note: Many Princess Titles Are Available Under the Call Number Juvenile Easy Disney

Princess Stories Easy Please note: Many princess titles are available under the call number Juvenile Easy Disney. Alsenas, Linas. Princess of 8th St. (Easy Alsenas) A shy little princess, on an outing with her mother, gets a royal treat when she makes a new friend. Andrews, Julie. The Very Fairy Princess Takes the Stage. (Easy Andrews) Even though Gerry is cast as the court jester instead of the crystal princess in her ballet class’s spring performance, she eventually regains her sparkle and once again feels like a fairy princess. Barbie. Barbie: Fairytale Favorites. (Easy Barbie) Barbie: Princess charm school -- Barbie: a fairy secret -- Barbie: a fashion fairytale -- Barbie in a mermaid tale -- Barbie and the three musketeers. Child, Lauren. The Princess and the Pea in Miniature : After the Fairy Tale by Hans Christian Andersen. (Easy Child) Presents a re-telling of the well-known fairy tale of a young girl who feels a pea through twenty mattresses and twenty featherbeds and proves she is a real princess. Coyle, Carmela LaVigna . Do Princesses Really Kiss Frogs? (Easy Coyle) A young girl takes a hike with her father, asking many questions along the way about what princesses do. Cuyler, Margery. Princess Bess Gets Dressed. (Easy Cuyler) A fashionably dressed princess reveals her favorite clothes at the end of a busy day. Disney. 5-Minute Princess Stories. (Easy Disney) Magical tales about princesses from different Walt Disney movies. Disney. Princess Adventure Stories. (Easy Disney) A collection of stories from favorite Disney princesses. Edmonds, Lyra. An African Princess. (Easy Edmonds) Lyra and her parents go to the Caribbean to visit Taunte May, who reminds her that her family tree is full of princesses from Africa and around the world. -

World Dog Show Leipzig 2017

WORLD DOG SHOW LEIPZIG 2017 09.-12. November 2017, Tag 2 in der Leipziger Messe Schirmherrin: Staatsministerin für Soziales und Verbraucherschutz Barbara Klepsch Patron: Minister of State for Social Affairs and Consumer Protection Barbara Klepsch IMPRESSUM / FLAG Veranstalter / Promoter: Verband für das Deutsche Hundewesen (VDH) e.V. Westfalendamm 174, 44141 Dortmund Telefon: (02 31) 5 65 00-0 Mo – Do 9.00 – 12.30/13.00 – 16.00 Uhr, Fr 9.00 – 12.30 Uhr Telefax: (02 31) 59 24 40 E-Mail: [email protected], Internet: www.vdh.de Chairmann/ Prof. Dr. Peter Friedrich Präsident der World Dog Show Secretary / Leif Kopernik Ausstellungsleitung Organization Commitee / VDH Service GmbH, Westfalendamm 174, 44141 Dortmund Organisation USt.-IdNr. DE 814257237 Amtsgericht Dortmund HRB 18593 Geschäftsführer: Leif Kopernik, Jörg Bartscherer TAGESEINTEILUNG / DAILY SCHEDULE FREITAG, 10.11.2017: Gruppe 5/ Group 5: Nordische Schlitten-, Jagd-, Wach- und Hütehunde, europäische und asiatische Spitze, Urtyp / Spitz and primitive types Gruppe 9 / Group 9: Gesellschafts- und Begleithunde / Companion and Toy Dogs TAGESABLAUF / DAILY ROUTINE 7.00 – 9.00 Uhr Einlass der Hunde / Entry for the Dogs 9.00 – 15.15 Uhr Bewertung der Hunde / Evaluation of the Dogs NOTICE: The World Winner 2017, World Junior Winner 2017 and the World Veteran Winner will get a Trophy. A Redelivery is not possible. HINWEIS: Die World Winner 2017, World Junior Winner 2017 und der World Veteranen Winner 2017 erhal- ten einen Pokal. Eine Nachlieferung ist nach der Veranstaltung nicht möglich. WETTBEWERBSRICHTER / JUDGES MAIN RING (WORLD DOG SHOW TAG 2) FREITAG, 10. NOVEMBER 2017 / FRIDAY, 10. NOVEMBER 2017 Junior Handling: Gerald Jipping (NLD) Zuchtgruppen / Best Breeders Group: Vija Klucniece (LVA) Paarklassen / Best Brace / Couple: Ramune Kazlauskaite (LTU) Veteranen / Best Veteran: Chan Weng Woh (MYS) Nachzuchtgruppen / Best Progeny Group: Dr. -

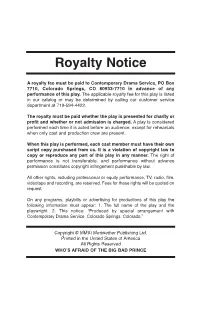

Royalty Notice

Royalty Notice A royalty fee must be paid to Contemporary Drama Service, PO Box 7710, Colorado Springs, CO 80933-7710 in advance of any performance of this play. The applicable royalty fee for this play is listed in our catalog or may be determined by calling our customer service department at 719-594-4422. The royalty must be paid whether the play is presented for charity or profit and whether or not admission is charged. A play is considered performed each time it is acted before an audience, except for rehearsals when only cast and production crew are present. When this play is performed, each cast member must have their own script copy purchased from us. It is a violation of copyright law to copy or reproduce any part of this play in any manner. The right of performance is not transferable, and performance without advance permission constitutes copyright infringement punishable by law. All other rights, including professional or equity performance, TV, radio, film, videotape and recording, are reserved. Fees for these rights will be quoted on request. On any programs, playbills or advertising for productions of this play the following information must appear: 1. The full name of the play and the playwright. 2. This notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Contemporary Drama Service, Colorado Springs, Colorado.” Copyright © MMXI Meriwether Publishing Ltd. Printed in the United States of America All Rights Reserved WHOS AFRAID OF THE BIG BAD PRINCE Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Prince A two-act fairy tale parody/mystery by Craig Sodaro Meriwether Publishing Ltd. -

To Whom the Shoe Fits: Cinderella As a Cultural Phenomenon in the Czech and Norwegian Context

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of Germanic, Nordic and Dutch Studies To Whom the Shoe Fits: Cinderella as a Cultural Phenomenon in the Czech and Norwegian Context 2020 Mgr. Adéla Ficová Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of Germanic, Nordic and Dutch Studies Norwegian Language and Literature Mgr. Adéla Ficová To Whom the Shoe Fits: Cinderella as a Cultural Phenomenon in the Czech and Norwegian Context M.A. Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Karolína Stehlíková, Ph.D. 2020 2 Statutory Declaration I hereby declare that I have written the submitted Master Thesis To Whom the Shoe Fits: Cinderella as a Cultural Phenomenon in the Czech and Norwegian Context independently. All the sources used for the purpose of finishing this thesis have been adequately referenced and are listed in the Bibliography. In Brno, 12 May 2020 ....................................... Mgr. Adéla Ficová 3 Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Mgr. Karolína Stehlíková, Ph.D., for her helpful guidance and valuable advices and shared enthusiasm for the topic. I also thank my parents and my friends for their encouragement and support. 4 Table of contents 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Literature review ..................................................................................................................... 8 2 Historical genesis of the Cinderella fairy tale ................................................................................ -

The Representation of Gender in Disney's Cinderella and Beauty

THE REPRESENTATION OF GENDER IN DISNEY’S CINDERELLA AND BEAUTY & THE BEAST A Comparative Analysis of Animation and Live-Action Disney Film LINDA HOUWERS SUPERVISOR: FRANK MEHRING S4251164 Houwers 4251164/ 2 Essay Cover Sheet AMERIKANISTIEK Teachers who will receive this document: Frank Mehring and Markha Valenta Title of document: The Representation of Gender in Disney’s Cinderella and Beauty & the Beast: A Comparative Analysis of Animation and Live-action Disney Film. Name of course: BA Thesis American Studies Date of submission: June 15, 2017 The work submitted here is the sole responsibility of the undersigned, who has neither committed plagiarism nor colluded in its production. Signed Name of student: Linda Houwers Student number: 4251164 Houwers 4251164/ 3 Abstract This work aims to explore the developments of the representation of gender in popular cultural productions over time. It will focus its research on a recent development within the popular Disney franchise: Live-action remakes of animated classics. In comparing and analyzing four case studies, two animated films and their live-action counterparts, this study seeks to form an idea of gender representation and its progression over time. Using gender theory by Judith Butler and a variety of theory on gender in media and culture specifically, an analysis focused on the representation of gender will be carried out for the chosen case studies of Cinderella (1950), Cinderella (2015), Beauty and the Beast (1991), and Beauty and the Beast (2017). The findings of this work conclude that the live-action case studies clearly reflect ongoing gender discourse and societal change, despite simultaneously still inhabiting some traditional stereotypes and ideas. -

Analysis of Cinderella Motifs, Italian and Japanese

Analysis of Cinderella Motifs, Italian and Japanese By C h ie k o I r ie M u lh e r n University of Illinois at Urbana—Champaign I ntroduction The Japanese Cinderella cycle is a unique phenomenon. It is found in the medieval literary genre known as otogizoshi 御 伽 草 子 (popular short stories that proliferated from the 14th to the mid-17th centuries). These are literary works which are distinguished from transcribed folk tales by their substantial length and scope; sophistication in plot struc ture, characterization, and style; gorgeous appearance in binding and illustration; and wide circulation. The origin, date, authorship, reader ship, means of circulation, and geographic distribution of the otogizoshi tales, which include some four hundred,remains largely nebulous. Particularly elusive among them is the Cinderella cycle, which has no traceable predecessors or apparent progeny within the indigenous or Oriental literary traditions. In my own previous article, ‘‘ Cinderella and the Jesuits ” (1979), I have established a hypothesis based on analysis of the tales and a com parative study of the Western Cinderella cycle. Its salient points are as follows: 1 . The Japanese tales show an overwhelming affinity to the Italian cycle. 2. The Western influence is traced to the Japanese-speaking Italian Jesuits stationed in Japan during the heyday of their missionary activity between 1570 and 1614; and actual authorship is attributable to Japa nese Brothers who were active in the Jesuit publication of Japanese- language religious and secular texts. 3. Their primary motive in writing the Cinderella tales seems to have been to proselytize Christianity and to glorify examplary Japanese Asian Folklore Studiest V ol.44,1985, 1-37. -

Rape in the Tale of Genji

SWEAT, TEARS AND NIGHTMARES: TEXTUAL REPRESENTATIONS OF SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN HEIAN AND KAMAKURA MONOGATARI by OTILIA CLARA MILUTIN B.A., The University of Bucharest, 2003 M.A., The University of Massachusetts Amherst, 2008 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2015 ©Otilia Clara Milutin 2015 Abstract Readers and scholars of monogatari—court tales written between the ninth and the early twelfth century (during the Heian and Kamakura periods)—have generally agreed that much of their focus is on amorous encounters. They have, however, rarely addressed the question of whether these encounters are mutually desirable or, on the contrary, uninvited and therefore aggressive. For fear of anachronism, the topic of sexual violence has not been commonly pursued in the analyses of monogatari. I argue that not only can the phenomenon of sexual violence be clearly defined in the context of the monogatari genre, by drawing on contemporary feminist theories and philosophical debates, but also that it is easily identifiable within the text of these tales, by virtue of the coherent and cohesive patterns used to represent it. In my analysis of seven monogatari—Taketori, Utsuho, Ochikubo, Genji, Yoru no Nezame, Torikaebaya and Ariake no wakare—I follow the development of the textual representations of sexual violence and analyze them in relation to the role of these tales in supporting or subverting existing gender hierarchies. Finally, I examine the connection between representations of sexual violence and the monogatari genre itself. -

Passive and Active Masculinities in Disney's Fairy Tale Films

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU ETD Archive 2013 Passive and Active Masculinities in Disney's Fairy Tale Films Grace DuGar Cleveland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/etdarchive Part of the English Language and Literature Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation DuGar, Grace, "Passive and Active Masculinities in Disney's Fairy Tale Films" (2013). ETD Archive. 387. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/etdarchive/387 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in ETD Archive by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PASSIVE AND ACTIVE MASCULINITIES IN DISNEY‘S FAIRY TALE FILMS GRACE DuGAR Bachelor of Arts in Political Science Denison University May 2008 submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY May 2013 This thesis has been approved for the Department of ENGLISH and the College of Graduate Studies by ____________________________________________________________ Thesis Chairperson, Rachel Carnell ______________________________ Department & Date ____________________________________________________________ James Marino ______________________________ Department & Date ___________________________________________________________ Gary Dyer ______________________________ Department & Date PASSIVE AND ACTIVE MASCULINITIES IN DISNEY‘S FAIRY TALE FILMS GRACE DuGAR ABSTRACT Disney fairy tale films are not as patriarchal and empowering of men as they have long been assumed to be. Laura Mulvey‘s cinematic theory of the gaze and more recent revisions of her theory inform this analysis of the portrayal of males and females in Snow White, Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, and Aladdin. -

A Survey of Slovenian Women Fairy Tale Writers

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 15 (2013) Issue 1 Article 3 A Survey of Slovenian Women Fairy Tale Writers Milena Mileva Blazić University of Ljubljana Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Other English Language and Literature Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Blazić, Milena Mileva "A Survey of Slovenian Women Fairy Tale Writers." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 15.1 (2013): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.2064> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. -

Who Is Cinderella,...Or Cinderfella?

1 Who is Cinderella, … or Cinderfella? Donna Rohanna Patterson Elementary School Overview Rationale Objectives Strategies Classroom Activities Annotated Bibliography/Resources Appendices/Standards Overview Folk and fairy tale stories comprise most of the stories children hear from birth to 2nd grade. They are used not only to entertain, but often as teaching stories about the dangers and values of life. These very same stories are shared in many cultures around the world. Although they vary in characters, setting, and texture from one continent to the next, they remain some of the most powerful stories for teaching and learning during the early years. Folk and fairy tales have initiated children into the ways of the world probably from time immemorial. Many have changed over time to homogenize into the variety that we often see and hear today to meet a more generic audience, often leaving behind the tales geographic and social origins. By exposing students to a variety of multicultural renditions of a classic Fairy Tale they can begin to relate to these stories in new ways, leading to a richer literary experience. Fairy Tales written through ethnic eyes also give a great deal of cultural information, which can result in a richer experience for the students and students. We can then appreciate the origins and adaptations as they have migrated through time and space. These stories help to make sense of the world for young children. Folk and fairy tales were not meant only for entertainment, they provide a social identity, and instill values as well as teaching lessons. In my own experience I have found that classrooms are often filled with students that either come from other countries or have families that do.