Master Document Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Window Dancing

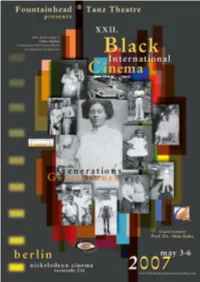

In Memoriam Harold Francis McKinney May 28, 1917 – November 7, 2006 The Talented Tenth “The problem of education, then, among Negroes must first of all deal with the Talented Tenth: it is the problem of developing the best of this race that they may guide the mass away from the contamination of the worst, in their own and other races.” W.E.B. DuBois FOREWORD Generations “A term referring to an approximation between the age of parents and the time their children were born.” The issue is, what has ensued during the generational time span of 20-25 years and how prepared were and are parents to provide the necessary educational, emotional, spiritual, physical and economic assets required for the development of the oncoming generations? What have been the experiences, accomplishments and perhaps inabilities of the parent generation and how will this equation impact upon the newcomers entering the world? The constant quest for human development is hopefully not supplanted by neglect, per- sonal or societal and therefore the challenge for each generation; are they prepared for their “turn” at the wheel of anticipated progress? How does each generation cope with the accomplishments and deficiencies from the previ- ous generation, when the baton is passed to the next group competing in the relay race of human existence? Despite the challenge of societal imbalance to the generations, hope and effort remain the constant vision leading to improvement accompanied and reinforced by determination and possible occurrences of “good luck,” to assist the generations and their offspring, neigh- bors and other members of the human family, towards as high a societal level as possible, in order to preserve, protect and project the present and succeeding generations into posi- tions of leverage thereby enabling them to confront the vicissitudes of life, manmade or otherwise. -

Chamber Dance Company FALLING

Contact: Lila Hurwitz/Doolittle+Bird [email protected] | 206.650.3305 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE UW DANCE PRESENTS Chamber Dance Company Presenting modern dance works of artistic and historic significance. FALLING Thursday–Saturday, October 10–12, 2019, 7:30pm Sunday, October 13, 2019, 2pm Meany Hall—Katharyn Alvord Gerlich Theater, UW Campus Pre-performance lectures 30 minutes before curtain with Sheila Farr, arts writer and UW alumna. Tickets: $12–22 / ArtsUW Ticket Office / ArtsUW.org / 206-543-4880 Info: dance.uw.edu / UW Department of Dance Facebook Chamber Dance Company’s 29th season explores the despair, thrill and humor intrinsic in the act of falling, with choreography by José Limón (1945), Brian Brooks (2012), Talley Beatty (1947) and Mark Morris (1982). Highlights include Brian Brooks’ First Fall (2012), a duet he created for acclaimed New York City Ballet ballerina Wendy Whelan. For the first time since exclusively performing and touring First Fall with Whelan, Brooks is sharing this work with Chamber Dance Company––the only company to perform the work since its premiere. With a mission of restaging and archiving significant works from the modern dance canon, Chamber Dance Company is one of the only companies in the country ensuring that these seminal masterworks are kept alive and accessible. About the Program & Choreographers: Concerto Grosso (1945) by José Limón. Staged by Brenna Monroe-Cook. An ebullient trio to music by Vivaldi, showcasing the suspension and fall on which Limón technique is based. Monroe-Cook received her MFA from the UW in 2011 and re-joined the José Limón Dance Company after graduation. -

Ruth Clark Lert Dance Library and Archive, 1831-1994

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf4779n8h6 No online items Guide to the Ruth Clark Lert Dance Library and Archive, 1831-1994 Processed by Laura Clark Brown; machine-readable finding aid created by Brooke Dykman Dockter Special Collections and Archives The UCI Libraries P.O. Box 19557 University of California Irvine, California 92623-9557 Phone: (949) 824-3947 Fax: (949) 824-2472 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.lib.uci.edu/rrsc/speccoll.html © 1997 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Note Arts and Humanities --Performing Arts --DanceGeographical (by Place) --California Guide to the Ruth Clark Lert MS-P009 1 Dance Library and Archive, 1831-1994 Guide to the Ruth Clark Lert Dance Library and Archive, 1831-1994 Collection number: MS-P 9 Special Collections and Archives The UCI Libraries University of California Irvine, California Contact Information Special Collections and Archives The UCI Libraries P.O. Box 19557 University of California Irvine, California 92623-9557 Phone: (949) 824-3947 Fax: (949) 824-2472 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.lib.uci.edu/rrsc/speccoll.html Processed by: Laura Clark Brown Date Completed: 1997 Encoded by: Brooke Dykman Dockter © 1997. The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Ruth Clark Lert Dance Library and Archive, Date (inclusive): 1831-1994 Date (bulk): (bulk 1950-1980) Collection number: MS-P009 Collector: Lert, Ruth Clark Extent: Number of containers: 65 document boxes, 3 shoe boxes, 8 record cartons, 10 flat boxes and 12 oversized folders Linear feet: 57 Repository: University of California, Irvine. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Glory Van Scott

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Glory Van Scott Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Van Scott, Glory Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Glory Van Scott, Dates: September 16, 2004 Bulk Dates: 2004 Physical 7 Betacame SP videocasettes (3:05:34). Description: Abstract: Dancer, theater professor, and stage actress Glory Van Scott (1947 - ) has acted in several plays and movies, and has written eight musicals. She has worked on many tributes to Katherine Dunham, and was awarded the first Katherine Dunham Legacy Award in 2002. She is also founded of Dr. Glory's Children's Theater. Van Scott was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on September 16, 2004, in New York, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2004_163 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Producer, performer, educator, and civic activist, Glory Van Scott, was born in Chicago, Illinois, June 1, 1947. Van Scott's parents, Dr. and Ms. Thomas Van Scott, were raised near Greenwood, Mississippi and shared some Choctaw and Seminole ancestry. The trauma of Van Scott's cousin Emmett Till’s murder in 1955 did not diminish the benefit of the art, dance, and drama classes at The Abraham Lincoln Center, where she met Paul Robeson and Charity Bailey. Van Scott spent summers in Ethical Culture Camp in New York. A student at Oakland Scott spent summers in Ethical Culture Camp in New York. -

African Dancing and Drumming in the Little Village of Tallahassee, Florida Andrea-Latoya Davis-Craig

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Building Community: African Dancing and Drumming in the Little Village of Tallahassee, Florida Andrea-Latoya Davis-Craig Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF VISUAL ARTS, THEATER, AND DANCE BUILDING COMMUNITY: AFRICAN DANCING AND DRUMMING IN THE LITTLE VILLAGE OF TALLAHASSEE, FLORIDA By ANDREA-LA TOYA DAVIS-CRAIG A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Art Education in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 Copyright © 2009 Andrea-La Toya Davis-Craig All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Andrea-La Toya Davis-Craig defended on 03-19-2009. ____________________________________ Pat Villeneuve Professor Directing Dissertation ____________________________________ Patricia Young Outside Committee Member ____________________________________ Marcia Rosal Committee Member ____________________________________ Tom Anderson Committee Member Approved: __________________________________ David Gussak, Chair, Department of Art Education The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii I am because you are. Dedicated to: My grandmother Aline Mickens Not a day goes by that I don’t think of you. I love you grandma. My grandmother Lottie Davis I never met you, but I know my dad and know that he is a reflection of you. My parents Lt. Col. Walter and Andrea Davis Your unyielding support, sacrifice, and example have taught me anything is possible. & My ancestors You fought the fight so that I could walk in the light. -

Katherine Dunham Collection

Katherine Dunham Collection Guides to Special Collections in the Music Division of the Library of Congress Music Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2018 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/perform.contact Catalog Record: https://lccn.loc.gov/2011570505 Additional search options available at: https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/eadmus.mu018008 Processed by the Music Division of the Library of Congress Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Music Division, 2017 Revised 2019 March Collection Summary Title: Katherine Dunham Collection Span Dates: 1920-2006 Call No.: ML31.D985 Creator: Dunham, Katherine Extent: 5,184 items plus digital materials Extent: 33 containers Extent: 15 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. LC Catalog record: https://lccn.loc.gov/2011570505 Summary: Katherine Dunham (1909-2006) was an American dancer, choreographer, teacher, dance anthropologist, and writer. The collection contains correspondence, awards and honors, writings by and about Dunham, business papers, photographs and videotapes, clippings and reviews, programs, promotional materials, and materials related to the Library of Congress Katherine Dunham Legacy Project. Online Content: Selections from the Katherine Dunham Collection are available on the Library of Congress website at http://lcweb2.loc.gov/diglib/ihas/html/dunham/dunham-home.html . Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the LC Catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically. People Dunham, Katherine--Archives. Dunham, Katherine--Correspondence. Dunham, Katherine--Photographs. Dunham, Katherine. -

Ruth Beckford Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8w0997v Online items available Guide to the Ruth Beckford Papers Sean Heyliger African American Museum & Library at Oakland 659 14th Street Oakland, California 94612 Phone: (510) 637-0198 Fax: (510) 637-0204 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.oaklandlibrary.org/locations/african-american-museum-library-oakland © 2013 African American Museum & Library at Oakland. All rights reserved. Guide to the Ruth Beckford MS 60 1 Papers Guide to the Ruth Beckford Papers Collection number: MS 60 African American Museum & Library at Oakland Oakland, California Processed by: Sean Heyliger Date Completed: 02/18/2015 Encoded by: Sean Heyliger © 2013 African American Museum & Library at Oakland. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Ruth Beckford papers Dates: 1915-1998 Collection number: MS 60 Creator: Beckford, Ruth. Collection Size: 11.5 linear feet(22 boxes + 1 oversized box) Repository: African American Museum & Library at Oakland (Oakland, Calif.) Oakland, CA 94612 Abstract: The Ruth Beckford Papers include dance programs, correspondence, lesson plans, oral histories, manuscripts, newspapers clippings, and photographs documenting Beckford’s career as a noted African-Haitian dancer, actress, and teacher. Languages: Languages represented in the collection: English Access No access restrictions. Collection is open to the public. Access Restrictions Materials are for use in-library only, non-circulating. Publication Rights Permission to publish from the Ruth Beckford Papers must be obtained from the African American Museum & Library at Oakland. Preferred Citation Ruth Beckford papers, MS 60, African American Museum & Library at Oakland, Oakland Public Library. Oakland, California. Beckford, Ruth, Penny Peak, and Jeff Friedman. Going for happiness: an oral history of Ruth Beckford. -

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater Judith Jamison, Artistic Director Masazumi Chaya, Associate Artistic Director Teacher Resource Guide 3 Table of Contents 3

1 1 university musical society 2000-2001 youth education Revelations alvin ailey american dance theater judith jamison, artistic director masazumi chaya, associate artistic director teacher resource guide 3 Table of Contents 3 Part I: An Overview of the Performance 5 How to Be a Good Audience Member the university musical society 6 Overview of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater 2000 - 2001 youth education program 9 Youth Performance Program 10 Phases 11 Revelations 14 What Makes an Ailey Performance? Part II: Biographies 17 University Musical Society 18 Arts League of Michigan 19 Detroit Opera House 21 Alvin Ailey Company History 23 Judith Jamison, Artistic Director 26 Masazumi Chaya, Associate Artistic Director 27 Rudy Hawkins Singers Part III: Dance 29 What is Dance? 31 Key Elements of Dance 24 Glossary of Dance Terms Part IV: Roots 40 “I am a Black man . .” by Alvin Ailey 41 African-American Sacred Music youth performances 46 The Development of Black Modern Dance in America thursday, february 1, 2001 Part V: Lesson Plans and Activities friday, february 2, 2001 50 Lesson Plans 51 State of Michigan Content Standards and Benchmarks: detroit opera house, detroit Meaningful Connections with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater 54 Lesson 1: Poetry Reading 56 Lesson 2: Movements from Revelations 58 Lesson 3: Inspirations 62 Lesson 4: Time, Space and Energy 63 Lesson 5: Ailey Newspaper The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater is co-presented by the University Musical Society, The Arts League of Michigan and the Detroit Opera House, with additional support 65 Bibiography/Recommended Reading from the Venture Fund for Cultural Participation of the Community Foundation for Southeastern Michigan and Wallace-Reader’s Digest Funds. -

Appendix 1: Joan Myers Brown — Annotated Resume

APPENDIX 1: JOAN MYERS BROWN — ANNOTATED RESUME Compiled by Brenda Dixon Gottschild with input from Takiyah Nur Amin and Nyama McCarthy Brown. Activities recorded through 2010. December 25, 1931: Joan, their fi rst and only child, is born to Julius and Nellie Myers at Graduate Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Joan and her parents live in Philadelphia, first at Sixteenth and Christian Streets until they move to Forty- Second and Woodland Streets in 1934/1935 and then to 4638 Paschall Avenue in 1938/1939. ( July 28, 1910: Julius Thomas Myers born in Wadesboro, North Carolina. Of seventeen siblings, he was the youngest of six of the brothers who moved to Philadelphia together around the end of the 1920s. He worked as a chef at 2601 Benjamin Franklin Parkway in Philadelphia. Later he owned a restaurant on Forty- Second and Woodland Street near the family residence. Thereafter, he worked at the Sun Ship Yard. Julius Myers’ mother, Mariah Sturdevant passed away in her early forties; Julius Myers said she was a Jewish woman of German descent. February 23, 1915: Nellie (Lewis) Myers born in Philadelphia, her family having migrated from Virginia. She attended the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy and Science in the 1930s and worked in the chemical research and chemical engineering department of the Arcos Corporation for thirty years.) 1937–1942 : Joan attends the Alexander Wilson Elementary School. 1938–1939: Joan Myers trains with Sydney King at Essie Marie Dorsey’s dance school and also with King in classes held in the basement of King’s residence to strengthen a broken foot. -

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater Artistic Director Robert Battle Announces Two‐Week Lincoln Center Engagement June 10 ‐ 21

Press Contacts: Christopher Zunner [email protected] / 212‐405‐9028 Emily Hawkins [email protected] / 212‐405‐9083 ALVIN AILEY AMERICAN DANCE THEATER ARTISTIC DIRECTOR ROBERT BATTLE ANNOUNCES TWO‐WEEK LINCOLN CENTER ENGAGEMENT JUNE 10 ‐ 21 AMERICA’S CULTURAL AMBASSADOR ALSO TO VISIT PARIS FOR LES ÉTÉS DE LA DANSE INTERNATIONAL DANCE FESTIVAL JULY 7 – AUGUST 1 AND RETURN TO SOUTH AFRICA FOR PERFORMANCES IN JOHANNESBURG AND CAPE TOWN SEPTEMBER 3 ‐ 20 Diverse Repertory for 15‐Performance Engagement at David H. Koch Theater Features World Premiere Exodus by Rennie Harris, Company Premiere of Robert Battle’s No Longer Silent, New Productions of Talley Beatty’s Toccata and Judith Jamison’s A Case of You Lincoln Center season tickets starting at $25 are on sale. New York – UPDATED June 3, 2015 – Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, beloved as one of the world’s most popular dance companies, will return to Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts for a two‐week 15‐ performance engagement at the David H. Koch Theater June 10 – 21, 2015, led by Artistic Director Robert Battle. Repertory for the season is highlighted by Exodus, a world premiere from bold hip‐hop choreographer Rennie Harris, the company premiere of Battle’s No Longer Silent, and new productions of Talley Beatty’s Toccata and Artistic Director Emerita Judith Jamison’s A Case of You duet from Reminiscin’. Recognized by U.S. Congressional Resolution as a vital American “Cultural Ambassador to the World,” the Ailey company also has major international appearances in 2015. A four‐week engagement at Paris’ Théâtre du Châtelet for Les Étés de la Danse International Dance Festival will take place July 7 – August 1. -

ABSTRACT Name: Debra J. Nelson Department: Counseling, Adult And

ABSTRACT Name: Debra J. Nelson Department: Counseling, Adult and Higher Education Title: Perceptions of the Meaning of Dance Choreography by Contemporary African-American Dancers, Choreographers, and Educators Major: Adult and Higher Education Degree: Doctor of Education Approved by: Amy D. Rose Date: Dissertation Director ' NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ABSTRACT This study explored the reasons why some African-American dancers, choreographers, and educators choreograph, how they choreograph, and what they choreograph about. This study investigated how the dance experience provides meaning for these individuals and their perceptions of the meaning of Black dance. Although we know dance has been used as a vehicle of expression for artists, and of particular interest in this study, the African-American artist, we do not know what the dance experience means to these individuals. Prior research has not explored the creation of dance as both a personal and cultural phenomenon for African Americans. No one has looked at how the African-American artist is impacted by internal and external forces and how these forces become manifested in the work they create. To examine these questions and uncover salient themes in the choreography of the African-American artists in this study, an interpretive qualitative design using life history was employed. Twelve professional African-American dancers, choreographers, and educators were interviewed about their experiences as choreographers. The analysis revealed how outside forces (i.e., life experience, socio-political and economic forces, history, music, and religion) impact the artists and become manifested in their choreographic works. The findings disclosed how Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

An Annotated Bibliography

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Scholarship at Penn Libraries Penn Libraries 2003 Autobiographies by Americans of Color 1995-2000: An Annotated Bibliography Rebecca A. Stuhr Penn Libraries, [email protected] Deborah Jean Iwabuchi [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/library_papers Part of the American Studies Commons, Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Stuhr, R. A., & Iwabuchi, D. J. (2003). Autobiographies by Americans of Color 1995-2000: An Annotated Bibliography. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/library_papers/82 Stuhr, Rebecca and Deborah Iwabuchi. Autobiographies by Americans of Color, 1995-2000: An Annotated Bibliography. Albany: Whitston Publishing, 2003; Stuhr-Iwabuchi Autobiographies by Americans of Color 1980-1994: An Annotated Bibliography by Rebecca A Stuhr & Deborah Jean Iwabuchi is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Based on a work at http://repository.upenn.edu/library_papers/82/. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/library_papers/82 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Autobiographies by Americans of Color 1995-2000: An Annotated Bibliography Abstract This second of two volumes bringing together as comprehensively as possible, all autobiographical works by Americans of Color covers the years 1995-2000. In this five year period there are nearly 200 more publications than in the previous volume (1980-1994), which spanned fifteen ears.y 435 of the 674 entries in this volume are by African Americans. The stories of leaving the south and participation in the Civil Rights Movement, which were present in the first olume,v are joined by those of musicians, entertainers, entrepreneurs, and athletes, teachers, sharecroppers, politicians, and veterans.