Vi. “One of the Unresolved Mysteries of History” 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ug Abuse and Dependence

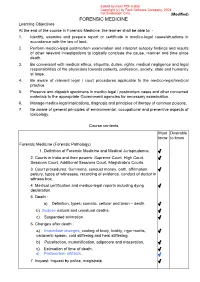

Edited by Foxit PDF Editor Copyright (c) by Foxit Software Company, 2004 For Evaluation Only. (Modified) FORENSIC MEDICINE Learning Objectives At the end of the course in Forensic Medicine, the learner shall be able to: - 1. Identify, examine and prepare report or certificate in medico-legal cases/situations in accordance with the law of land. 2. Perform medico-legal postmortem examination and interpret autopsy findings and results of other relevant investigations to logically conclude the cause, manner and time since death. 3. Be conversant with medical ethics, etiquette, duties, rights, medical negligence and legal responsibilities of the physicians towards patients, profession, society, state and humanity at large. 4. Be aware of relevant legal / court procedures applicable to the medico-legal/medical practice. 5. Preserve and dispatch specimens in medico-legal / postmortem cases and other concerned materials to the appropriate Government agencies for necessary examination. 6. Manage medico-legal implications, diagnosis and principles of therapy of common poisons. 7. Be aware of general principles of environmental, occupational and preventive aspects of toxicology. Course contents Must Desirable know to know Forensic Medicine (Forensic Pathology) 1. Definition of Forensic Medicine and Medical Jurisprudence. √ 2. Courts in India and their powers: Supreme Court, High Court, √ Sessions Court, Additional Sessions Court, Magistrate’s Courts. 3. Court procedures: Summons, conduct money, oath, affirmation, √ perjury, types of witnesses, recording of evidence, conduct of doctor in witness box, 4. Medical certification and medico-legal reports including dying √ declaration. 5. Death : a) Definition, types; somatic, cellular and brain – death. √ b) Sudden natural and unnatural deaths. √ c) Suspended animation. √ 6. -

Thailand's Red Networks: from Street Forces to Eminent Civil Society

Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Freiburg (Germany) Occasional Paper Series www.southeastasianstudies.uni-freiburg.de Occasional Paper N° 14 (April 2013) Thailand’s Red Networks: From Street Forces to Eminent Civil Society Coalitions Pavin Chachavalpongpun (Kyoto University) Pavin Chachavalpongpun (Kyoto University)* Series Editors Jürgen Rüland, Judith Schlehe, Günther Schulze, Sabine Dabringhaus, Stefan Seitz The emergence of the red shirt coalitions was a result of the development in Thai politics during the past decades. They are the first real mass movement that Thailand has ever produced due to their approach of directly involving the grassroots population while campaigning for a larger political space for the underclass at a national level, thus being projected as a potential danger to the old power structure. The prolonged protests of the red shirt movement has exceeded all expectations and defied all the expressions of contempt against them by the Thai urban elite. This paper argues that the modern Thai political system is best viewed as a place dominated by the elite who were never radically threatened ‘from below’ and that the red shirt movement has been a challenge from bottom-up. Following this argument, it seeks to codify the transforming dynamism of a complicated set of political processes and actors in Thailand, while investigating the rise of the red shirt movement as a catalyst in such transformation. Thailand, Red shirts, Civil Society Organizations, Thaksin Shinawatra, Network Monarchy, United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship, Lèse-majesté Law Please do not quote or cite without permission of the author. Comments are very welcome. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the author in the first instance. -

DOA Stories and Questions

Name:_________________ Hour:_______ Dead On Arrival Articles Getting Rid of the Body !Criminals don"t like to leave behind evidence, although they usually do. In a murder, the primary bit of evidence is obviously the body. Sometimes a murderer attempts to completely destroy the body of a victim, reasoning that no body means no conviction. Not true -- convictions have been obtained even when no body is found. Regardless, destroying a body is no easy task. Fire seems to be the favorite tool of murderers looking to cover their tracks, but its almost never successful. Short of a crematorium, creating a fire that burns hot enough and long enough to destroy a human corpse is nearly impossible. !Another favorite is quicklime, which murderers often have seen used in the movies. Knowing the chemistry behind it might make them think twice about this one. Quicklime is calcium oxide. When it contacts water, as it often does in burial sites, it reacts with the water to make calcium hydroxide, also known as slaked lime. This corrosive material may damage the surface of the corpse, but the heat produced from its activity kills many of the putrefying bacteria and dehydrates the body, thereby preventing decay and promoting mummification. Thus, the use of quicklime actually may help preserve the body. !Acids also are commonly used by ill-informed criminals hoping to dissolve the body, which is not only difficult but extremely hazardous. Acids that are powerful enough to dissolve a body exist, but they require a great deal of time to complete the task. -

Thailand's Moment of Truth — Royal Succession After the King Passes Away.” - U.S

THAILAND’S MOMENT OF TRUTH A SECRET HISTORY OF 21ST CENTURY SIAM #THAISTORY | VERSION 1.0 | 241011 ANDREW MACGREGOR MARSHALL MAIL | TWITTER | BLOG | FACEBOOK | GOOGLE+ This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. This story is dedicated to the people of Thailand and to the memory of my colleague Hiroyuki Muramoto, killed in Bangkok on April 10, 2010. Many people provided wonderful support and inspiration as I wrote it. In particular I would like to thank three whose faith and love made all the difference: my father and mother, and the brave girl who got banned from Burma. ABOUT ME I’m a freelance journalist based in Asia and writing mainly about Asian politics, human rights, political risk and media ethics. For 17 years I worked for Reuters, including long spells as correspondent in Jakarta in 1998-2000, deputy bureau chief in Bangkok in 2000-2002, Baghdad bureau chief in 2003-2005, and managing editor for the Middle East in 2006-2008. In 2008 I moved to Singapore as chief correspondent for political risk, and in late 2010 I became deputy editor for emerging and frontier Asia. I resigned in June 2011, over this story. I’ve reported from more than three dozen countries, on every continent except South America. I’ve covered conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Lebanon, the Palestinian Territories and East Timor; and political upheaval in Israel, Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand and Burma. Of all the leading world figures I’ve interviewed, the three I most enjoyed talking to were Aung San Suu Kyi, Xanana Gusmao, and the Dalai Lama. -

A Short Account of the Rise and Fall of the Thai Technocracy

A Short Account of the Rise and Fall of the Thai Technocracy Pasuk Phongpaichit* and Chris Baker** Thailand’s sustained growth from the 1960s to 1990s was often attributed to a strong technocracy relatively free of political influence. Members of the first cadre of technocrats, which emerged in the 1950s, were mostly educated in Europe. In the “American” era, more were educated in the United States and believed the role of government was to provide a safe and liberal environment for capital, mostly through a fixed exchange rate and balanced budget. After 1975 the technocrats had to manage a more complex environment because of internal political conflicts and external shocks. They became more powerful because their skills were in demand and because they had strong backing from international institutions. During the boom that began in the mid 1980s, their grip on policy diminished. After the finan- cial crisis of 1997, the technocrats were blamed for not adjusting to changes in the domestic and international economy. Keywords: Thailand, technocrat, development policy, financial crisis In the 1990s, it became conventional to attribute the extraordinary success of the Thai economy to careful and conservative management by technocrats. After World War II, Thailand had been one of the most backward economies in Asia, lacking even basic insti- tutions implanted elsewhere by colonial governments. For the next half century, the economy grew at a cumulative average rate of over 7% a year, without once coming even close to a year of the negative growth experienced by most other Southeast Asian coun- tries during the oil shocks. -

The Democracy Monument: Ideology, Identity, and Power Manifested in Built Forms อนสาวรุ ยี ประชาธ์ ปไตยิ : อดมการณุ ์ เอกลกษณั ์ และอำนาจ สอผ่ื านงานสถาป่ ตยกรรมั

The Democracy Monument: Ideology, Identity, and Power Manifested in Built Forms อนสาวรุ ยี ประชาธ์ ปไตยิ : อดมการณุ ์ เอกลกษณั ์ และอำนาจ สอผ่ื านงานสถาป่ ตยกรรมั Assistant Professor Koompong Noobanjong, Ph.D. ผชู้ วยศาสตราจารย่ ์ ดร. คมพงศุ้ ์ หนบรรจงู Faculty of Industrial Education, King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology, Ladkrabang คณะครุศาสตร์อุตสาหกรรม สถาบันเทคโนโลยีพระจอมเกล้าเจ้าคุณทหารลาดกระบัง Abstract This research article examines the methods of power mediation in the design of the Democracy Monument in Bangkok, Thailand. It examines its underlying concept and mechanisms for conveying political power and social practice, along with the national and cultural identity that operates under an ideological framework. The study consists of two major parts. First, it investigates the monument as a political form of architecture: a symbolic device for the state to manifest, legitimize, and maintain power. The focus then shifts to an architectural form of politics: the ways in which ordinary citizens re-appropriated the Democracy Monument through semantic subversions to perform their social and political activities as well as to form their modern identities. Via the discourse theory, the analytical and critical discussions further reveal complexity, incongruity, and contradiction of meanings in the design of the monument in addition to paradoxical relationships with its setting, Rajadamnoen Avenue, which resulted from changes in the country’s socio-political situations. บทคดยั อ่ งานวิจัยชิ้นนี้ศึกษากระบวนการสื่อผ่านอำนาจอนุสาวรีย์ประชาธิปไตย -

Dynamics and Institutionalization of Coup in Thai Constitution"

Acknowledgements This paper is the product of my research as a research fellow (VRF) at the Institute of Developing Economies (IDE-JETRO) from November 2012 to March 2013. I would like to express my appreciation to IDE-JETRO for giving me the opportunity that enabled me to write this paper. I wish to thank Shinya Imaizumi for his support and suggestions during my stay at IDE- JETRO. I would like to thank Shinichi Shigetomi for his critical comments and suggestions during our discussions over lunch. I would like to thank Mr. Takao Tsuneishi and Ms. Chisato Ishii of the International Exchange Department for their invaluable help and advice from my first day in Chiba until my last; without their assistance, my sojourn would have been more challenging. I deeply appreciate the friendship and support I received from several friends at IDE-JETRO. Tsuruyo Funatsu, Nobu Aizawa, Maki Aoki, Tatsufumi Yamagata and Koo Boo Tek offered me their friendship, advice, and intellectual counsel along with many delightful lunches and dinners. -i- Table of Contents Acknowledgements i 1. Introduction 1 2. Constitutional Principles and Problems 2 3. Early Democracy and Disorderliness of the Coups 8 4. The Construction of the Coup Institution 18 5. Institutionalization of the Coup in the Thai Constitution 26 6. Conclusion: From Alienation to Constitutional Institution 32 Bibliography 35 The Author 36 -ii- List of Tables and Images Tables Table 1: Constitutions and Charters in Thailand 1932-2012 4 Table 2: Coups and the Amnesty Laws 15 Table 3: Authoritarian Power in Constitutions and Charters following Successful Coups 24 Table 4: Constitutional Revocation and Proclamation and the Period of Vacuum 27 Images Image 1: Declaration of Royal Appointment without Countersignature 13 -iii- 1. -

Bhumibol Adulyadej, the King of Thailand

Bhumibol Adulyadej, the king of Thailand. The current king of Thailand, Bhumibol Adulyadej, is the longest-reigning monarch in the world today, as well as Thailand's longest-reigning king ever. The beloved king's common name is pronounced "POO- mee-pohn uh-DOON-ja-deht"; his throne name is Rama IX. Early Life: Born a second son, and with his birth taking place outside of Thailand, Bhumibol Adulyadej was never meant to rule. His reign came about through a mysterious act of violence. Since then, the King has been a calm presence at the center of Thailand's stormy political life. On December 5, 1927, a Thai princess gave birth to a son named Bhumibol Adulyadej ("Strength of the Land, Incomparable Power") in a Cambridge, Massachusetts hospital. The family was in the United States because the child's father, Prince Mahidol, Mysterious Succession: was studying for a Public Health certificate at On June 9, 1946, King Ananda Mahidol died Harvard University. His mother studied in his palace bedroom of a single gunshot nursing at Simmons College. The boy was wound to the head. It was never conclusively the second son for Prince Mahidol and proven whether his death was murder, Princess Srinagarindra. accident or suicide, although two royal pages When Bhumibol was a year old, his family and the king's personal secretary were returned to Thailand, where his father took convicted and executed for assassinating up an intership in a hospital in Chiang Mai. him. Prince Mahidol was in poor health, though, 18-year-old Prince Bhumibol had gone in to and died of kidney and liver failure in his brother's room about 20 minutes before September of 1929. -

BANGKOK 101 Emporium at Vertigo Moon Bar © Lonely Planet Publications Planet Lonely © MBK Sirocco Sky Bar Chao Phraya Express Chinatown Wat Phra Kaew Wat Pho (P171)

© Lonely Planet Publications 101 BANGKOK BANGKOK Bangkok In recent years, Bangkok has broken away from its old image as a messy third-world capital to be voted by numerous metro-watchers as a top-tier global city. The sprawl and tropical humidity are still the city’s signature ambassadors, but so are gleaming shopping centres and an infectious energy of commerce and restrained mayhem. The veneer is an ultramodern backdrop of skyscraper canyons containing an untamed universe of diversions and excesses. The city is justly famous for debauchery, boasting at least four major red-light districts, as well as a club scene that has been revived post-coup. Meanwhile the urban populous is as cosmopolitan as any Western capital – guided by fashion, music and text messaging. But beside the 21st-century façade is a traditional village as devout and sacred as any remote corner of the country. This is the seat of Thai Buddhism and the monarchy, with the attendant splendid temples. Even the modern shopping centres adhere to the old folk ways with attached spirit shrines that receive daily devotions. Bangkok will cater to every indulgence, from all-night binges to shopping sprees, but it can also transport you into the old-fashioned world of Siam. Rise with daybreak to watch the monks on their alms route, hop aboard a long-tail boat into the canals that once fused the city, or forage for your meals from the numerous and lauded food stalls. HIGHLIGHTS Joining the adoring crowds at Thailand’s most famous temple, Wat Phra Kaew (p108) Escaping the tour -

Centara Grand at Centralworld Contact Details

Centara Grand at CentralWorld Contact Details Property Code: CGCW Official Star Rating: 5 Address: 999/99 Rama 1 Road,Pathumwan Bangkok 10330,Thailand Telephone: (+66) 2-100-1234 Hotel Fax: (+66) 2-100-1235 E-mail: [email protected] Official Hours of Operation: 24 hours GPS Longtitude: 100.539515018463 GPS Latitude: 13.7468157419102 General Manager Tel: (+66) 2-100-1234 #6100 Administrator Tel: (+66) 2-100-1234 Reservation Tel: (+66) 2-100-1234 #1 Reception Tel: (+66) 2-100-1234 #14 Sales Tel: (+66) 2-100-1234 #6547 Google my Business URL: https://goo.gl/maps/VkGDcCXES76QzH7X6 Google my Direction URL: https://www.google.com/maps/dir//999+Centara+Grand+at+CentralWorld,+99+Rama+I+Rd,+Pathum+Wan,+Pathum+W an+District,+Bangkok+10330/@13.747717,100.5365583,17z/data=!4m8!4m7!1m0!1m5!1m1!1s0x30e2992f7809567f:0xccc050cff0e7d 234!2m2!1d100.538747!2d13.747717 Recommended For Centara Grand at CentralWorld Families Single travellers Couples and honeymooners Business travellers MICE Shoppers Young travellers Group of friends Centara Grand at CentralWorld Building Total number of building(s) 1 Building: Centara Grand & Bangkok Convention Centre at CentralWorld Building name: Centara Grand & Bangkok Convention Centre at CentralWorld Year built: 2008 Last renovated in: - How many floors: 55 How many rooms: 505 Number of keys: 512 Location: Central to the business district, Centara Grand and Bangkok Convention Centre at CentralWorld is connected to major shopping and entertainment complexes by skywalk, and offer easy access to the mass transit systems. A rapid rail link directly to and from Suvarnabhumi Airport where travellers can check-in their luggage before boarding the train is 10 minutes away from the hotel. -

A Coup Ordained? Thailand's Prospects for Stability

A Coup Ordained? Thailand’s Prospects for Stability Asia Report N°263 | 3 December 2014 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Thailand in Turmoil ......................................................................................................... 2 A. Power and Legitimacy ................................................................................................ 2 B. Contours of Conflict ................................................................................................... 4 C. Troubled State ............................................................................................................ 6 III. Path to the Coup ............................................................................................................... 9 A. Revival of Anti-Thaksin Coalition ............................................................................. 9 B. Engineering a Political Vacuum ................................................................................ 12 IV. Military in Control ............................................................................................................ 16 A. Seizing Power -

JSS 097 0B Front

The Journal of the Siam Society Patrons of the Siam Society Patron His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej Vice-Patrons Her Majesty Queen Sirikit His Royal Highness Crown Prince Maha Vajiralongkorn Vice-Patron & Honorary President Her Royal Highness Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Honorary Vice-Presidents Her Majesty Ashi Kesang Choeden Wangchuck, The Royal Grandmother of Bhutan His Imperial Highness Prince Akishino of Japan His Royal Highness Crown Prince Frederik of Denmark Council of the Siam Society, 2008 - 2010 President Mr Athueck Asvanund Vice-President Mrs Bilaibhan Sampatisiri Leader, Natural History Section Dr Weerachai Nanakorn Honorary Secretary Mr Barent Springsted Honorary Treasurer Mr Suraya Supanwanich Honorary Librarian Ms Anne Sutherland Honorary Editor, JSS Dr Chris Baker Honorary Editor, NHB Dr William Schaedla Members of Council Mrs Eileen Deeley Ms Raksaswan Chrongchitpracharon Dr Nirun Jivasantikarn Mr Peter Laverick Mrs Beatrix Latham Mr James D Lehman H.E. Mr Juan Manuel Lopez Nadal Mr Paul Russell The Journal of the Siam Society Volume 97 2009 As this volume was in press, in May 2009, the Society received the information that Her Royal Highness Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn had graciously accepted to become Honorary President of the Society, in addition to being a Vice-Patron. The President, Council, and Society members wish to express their gratitude to Her Royal Highness for honouring the Society in this way. Editorial Board Tej Bunnag advisor Chris Baker advisor and honorary editor Michael Smithies editor Kanitha Kasina-Ubol coordinator Euayporn Kerdchouay production assistant © The Siam Society 2009 ISSN 0857-7099 Cover: A tinted lithograph by Delaporte, showing the Lao weights in use in the market in Luang Prabang, in François Garnier, Voyage d’exploration en Indo-Chine effectué pendant les années 1688, 1867, et 1868.