The Kamp Katrina Project: a Conversation with the Filmmakers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keepin' Your Head Above Water

Know Your Flood Protection System Keepin’ Your Head Above Water Middle School Science Curriculum Published by the Flood Protection Authority – East floodauthority.org Copyright 2018 Keepin’ Your Head Above Water: Know Your Flood Protection System PREFACE Purpose and Mission Our mission is to ensure the physical and operational integrity of the regional flood risk management system in southeastern Louisiana as a defense against floods and storm surge from hurricanes. We accomplish this mission by working with local, regional, state, and federal partners to plan, design, construct, operate and maintain projects that will reduce the probability and risk of flooding for the residents and businesses within our jurisdiction. Middle School Science Curriculum This Middle School Science Curriculum is part of the Flood Protection Authority – East’s education program to enhance understanding of its mission. The purposes of the school program are to ensure that future generations are equipped to deal with the risks and challenges associated with living with water, gain an in-depth knowledge of the flood protection system, and share their learning experiences with family and friends. The curriculum was developed and taught by Anne Rheams, Flood Protection Authority – East’s Education Consultant, Gena Asevado, St. Bernard Parish Public Schools’ Science Director, and Alisha Capstick, 8th grade Science Teacher at Trist Middle School in Meraux. La. The program was encouraged and supported by Joe Hassinger, Board President of the Flood Protection Authority – East and Doris Voitier, St. Bernard Parish Public Schools Superintendent. The curriculum was developed in accordance with the National Next Generation Science Standards and the Louisiana Department of Education’s Performance Expectations. -

After Hurricane Katrina: a Review of Community Engagement Activities and Initiatives

After Hurricane Katrina: a review of community engagement activities and initiatives August 2019 Summary This review examines how communities took control of their response to Hurricane Katrina through intracommunity engagement initiatives and how communities affected by Hurricane Katrina were engaged by organisations after the disaster occurred. This examination includes an overview of what ‘went well’ and what problems arose in those engagement efforts. The review indicates that communities were not passive in accepting decisions made by authorities that had not engaged with their wishes: where intracommunity decisions had been made, those communities fought for those choices to be upheld by authorities. Where organisations launched engagement activities, several focused on poor neighbourhoods that were badly affected by Katrina, and the children and young people living there. Fewer examples were identified of older people’s engagement by organisations or programmes. Engagement initiatives identified were, in several cases, reflective of the cultural context of the areas affected by Katrina: in particular, music played a key role in successful community engagement initiatives. Background 1 Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast of the United States in August 2005. New Orleans was flooded as a result of levees failing, and approximately 80 per cent of the city’s population was forced to evacuate.1 President George W Bush declared a state of emergency in Louisiana, Alabama, and Mississippi on 27 August 2005, which preceded mandatory evacuation orders in several affected areas of these states, including New Orleans. Many people living in poorer areas of the city were not 1 Institute of Medicine of the National Academies (2015) Health, resilient, and sustainable communities after disasters: strategies, opportunities, and planning for recovery, available at: https://dornsife.usc.edu/assets/sites/291/docs/AdaptLA_Workshops/Healthy_Resilient_Sustainable_C ommunities_After_Disasters.pdf, at page 244. -

Following Is a List of All 2019 Festival Jurors and Their Respective Categories

Following is a list of all 2019 Festival jurors and their respective categories: Feature Film Competition Categories The jurors for the 2019 U.S. Narrative Feature Competition section are: Jonathan Ames – Jonathan Ames is the author of nine books and the creator of two television shows, Bored to Death and Blunt Talk His novella, You Were Never Really Here, was recently adapted as a film, directed by Lynne Ramsay and starring Joaquin Phoenix. Cory Hardrict– Cory Hardrict has an impressive film career spanning over 10 years. He currently stars on the series The Oath for Crackle and will next be seen in the film The Outpostwith Scott Eastwood. He will star and produce the film. Dana Harris – Dana Harris is the editor-in-chief of IndieWire. Jenny Lumet – Jenny Lumet is the author of Rachel Getting Married for which she received the 2008 New York Film Critics Circle Award, 2008 Toronto Film Critics Association Award, and 2008 Washington D.C. Film Critics Association Award and NAACP Image Award. The jurors for the 2019 International Narrative Feature Competition section are: Angela Bassett – Actress (What’s Love Got to Do With It, Black Panther), director (Whitney,American Horror Story), executive producer (9-1-1 and Otherhood). Famke Janssen – Famke Janssen is an award-winning Dutch actress, director, screenwriter, and former fashion model, internationally known for her successful career in both feature films and on television. Baltasar Kormákur – Baltasar Kormákur is an Icelandic director and producer. His 2012 filmThe Deep was selected as the Icelandic entry for the Best Foreign Language Oscar at the 85th Academy Awards. -

The Emotional Context of Higher Education Community Engagement J

The Emotional Context of Higher Education Community Engagement J. Ashleigh Ross and Randy Stoecker Abstract Higher education community engagement has an emotional context, especially when it focuses on people who have been traumatized by oppression, exploitation, and exclusion. The emotional trauma may be multiplied many times when those people are also dealing with the unequally imposed consequences of disasters. This paper is based on interviews with residents of the Lower 9th Ward of New Orleans who experienced various forms of higher education community engagement in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. The results are surprising. First, residents most appreciated the sense of emotional support they received from service learners and volunteers, rather than the direct service those outsiders attempted to engage in. Second, residents did not distinguish between traditional researchers and community-based researchers, and perceived researchers in general as insensitive to community needs. The article explores the implications of these findings for preparing students and conducting research in any context involving emotional trauma. The practices of higher education community The Case of the Lower 9th Ward engagement—service learning, community-based The Lower 9th Ward in New Orleans is east research, and similar practices going under and down river of the central city and the French different labels—have in common their focus on Quarter. Landowners originally built plantations people who are suffering from exclusion, oppres- in long strips extending from the river to the sion, and exploitation in contemporary society. Bayou Bienvenue for river access, and located In essence, the targets of our service are people plantation houses on the highest elevations. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Imagine the Future Of

imagine the future of our vision Imagine a Christian University that is a national model for student success within an inclusive community. Imagine a Christian University that advances the calling of our students through teaching, learning, engaging, and serving. Imagine a Christian University that is defined by the opportunities we create, by the lives we transform, and by the futures we shape. You have imagined the University we seek to become. Chowanour University, mission grounded in its Christian faith, transforms the lives of students of promise. our values Faith. Inlcusion. Imagination. Engagement. SUPPORT THE VISION AT CHOWAN.EDU/WEGIVE CHOWAN UNIVERSITY HONOR ROLL OF INVESTORS 2016 - 2017 The Honor Roll of Investors lists gifts to the University received between June 1, 2016 and May 31, 2017. We are deeply grateful to the following alumni & friends. New Endowed Scholarships * Mr. & Mrs. Wayne Brown VA Power Matching Gift Program Mrs. Janelle Greene Ezzell Carlyle R. Wimbish, Jr. Scholarship James E. & Mary Bryan Foundation † Estate of Howard C. Vaughan Bill Pataky & Yolanda Faile Sheryl Brown Whitley Scholarship Mr. & Mrs. Percy Bunch Mr. Jesse E. Vaughan Mrs. Edith Vick Farris Gilbert and Linda Tripp Scholarship Burroughs Wellcome Fund Mr. & Mrs. Hugh C. Vincent Mr. & Mrs. Ray Felton Mary Peele Deanes Scholarship The Cannon Foundation, Inc. Wachovia Foundation † Mr. Henry Clay Ferebee III Newsome Family Scholarship CBF of North Carolina, Inc. MRP † Estate of Mr. A.J. Watkins † Mr. John Ed Ferebee Sports Studies Scholarship CIAA Tournament Mrs. Linda B. Weaver † Mrs. Beatrice “Bea” Flythe Mary Worrell Felton Carter, Benjamin Franklin Commercial Ready Mix Products Mr. -

Form B − Building

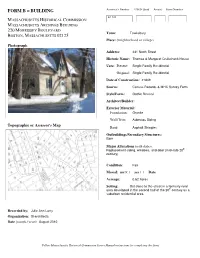

FORM B −−− BUILDING Assessor’s Number USGS Quad Area(s) Form Number 64 124 MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL COMMISSION MASSACHUSETTS ARCHIVES BUILDING 220 MORRISSEY BOULEVARD Town: Tewksbury BOSTON , MASSACHUSETTS 02125 Place: (neighborhood or village ) Photograph Address: 441 North Street Historic Name: Thomas & Margaret Cruikshank House Uses: Present: Single Family Residential Original: Single Family Residential Date of Construction: c1849 Source: Census Records & MHC Survey Form Style/Form: Gothic Revival Architect/Builder: Exterior Material: Foundation: Granite Wall/Trim: Asbestos Siding Topographic or Assessor's Map Roof: Asphalt Shingles Outbuildings/Secondary Structures: Barn Major Alterations (with dates ): Replacement siding, windows, and door (mid–late 20 th century) Condition: Fair Moved: no |X | yes | | Date Acreage: 0.62 Acres Setting: Set close to the street in a formerly rural area developed in the second half of the 20 th century as a suburban residential area. Recorded by: Julie Ann Larry Organization: ttl-architects Date ( month / year) : August 2010 Follow Massachusetts Historical Commission Survey Manual instructions for completing this form. INVENTORY FORM B CONTINUATION SHEET TEWKSBURY 441 NORTH STREET MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL COMMISSION Area(s) Form No. 220 MORRISSEY BOULEVARD , BOSTON , MASSACHUSETTS 02125 TEW.22 ___ Recommended for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. If checked, you must attach a completed National Register Criteria Statement form. Use as much space as necessary to complete the following entries, allowing text to flow onto additional continuation sheets. ARCHITECTURAL DESCRIPTION: Describe architectural features. Evaluate the characteristics of this building in terms of other buildings within the community . 441 North Street is a one-and-a-half story Gothic Revival comprised of a rectangular of a main block set on a field stone foundation with a one-and-a-half story rear ell. -

Watch Run Ronnie Run for Free

Watch run ronnie run for free Run Ronnie Run The film is about a redneck and his mystery which makes him become a star in his ơn reality program although he is arresting. What is his. Run Ronnie Run () Comedy [USA:R, 1 h 40 min] Bruce Taylor, David . appreciate it being a free movie. Watch Run Ronnie Run Online | run ronnie run | Run Ronnie Run () | Director: Troy Miller | Cast. Watch Run Ronnie Run Full Movie Run Ronnie Run is a heart warming spinoff from the cult hit HBO series Mr Show It is the story of Ronwell Quincy Dobbs. Buy Run Ronnie Run: Read 46 Movies & TV Reviews - Available to watch on supported devices. Send us Feedback | Get Help. By placing your. Watch Run Ronnie Run Online - Free Streaming Full Movie on Putlocker. Run Ronnie Run is a heart warming spin-off from the cult hit HBO series "Mr. Subscribe for more B-Movies, and Cult Cinema! Source: ?v=Ie61gfUAm10Uploader: B-Movie ArchiveUpload date: Run Ronnie Run is a film directed by Troy Miller director. The film is about a redneck. He has a strange tip for getting arrested, which helps him become the star. Watch the latest full length Putlocker and Megshare movies on Vumoo. Run Ronnie Run. 45min Comedy. A redneck with an uncanny talent for getting. Comedy · A redneck with an uncanny knack for getting arrested becomes the star of his own Watch Now. From $ (SD) Comedy to watch. a list of 36 titles. Run Ronnie Run The film is about a redneck and his mystery which makes him become a star in his Æ¡n reality program although he is arresting. -

“TERRIFICALLY ENGAGING.” – Variety

“TERRIFICALLY ENGAGING.” – Variety “BOBCAT GOLDTHWAIT’S MASTERPIECE. A TRULY BEAUTIFUL HUMAN DOCUMENT.” – Drew McWeeny, Hitfix 2015 CALL ME LUCKY a film by Bobcat Goldthwait CALL ME LUCKY is an inspiring, triumphant and wickedly funny documentary with a compelling and controversial hero at its heart. Barry Crimmins, best known as a comedian and political satirist, bravely tells his incredible story of transformation with intimate interviews from comedians such as David Cross, Margaret Cho and Patton Oswalt, activists such as Billy Bragg and Cindy Sheehan and directed in inimitable style by Bobcat Goldthwait (World’s Greatest Dad/God Bless America/Willow Creek). As a young and hungry comic in the early 80’s Barry Crimmins founded his own comedy club in Boston, in a Chinese restaurant called the Ding Ho. Here he fostered the careers of new talent who we now know as Steven Wright, Paula Poundstone, Denis Leary, Lenny Clarke, Kevin Meaney, Bobcat Goldthwait, Tom Kenny and many others. These comics were grateful for Barry’s fair pay and passionate support and respected him as a whip-smart comic himself but, as becomes clear in their interviews, they also knew he was tortured by his past. As archive footage of Barry shows, he was thickly mustachioed, thick set and thinly disguising an undercurrent of rage beneath his beer swilling onstage act. It seemed Barry was the fierce defender of the little guy but also an angry force when confronted. As one of the top new comedians in the country he appeared on The HBO Young Comedians Special, The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, Evening at the Improv and many other television shows in the 80’s. -

The Free Press Vol. 40, Issue No. 14, 02-09-2009

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Free Press, The, 1971- Student Newspapers 2-9-2009 The Free Press Vol. 40, Issue No. 14, 02-09-2009 Matt Dodge University of Southern Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/free_press Recommended Citation Dodge, Matt, "The Free Press Vol. 40, Issue No. 14, 02-09-2009" (2009). Free Press, The, 1971-. 58. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/free_press/58 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Free Press, The, 1971- by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. the free pressVolume 40, Issue No. 14 February 9, 2009 U S M EYE’ll be back USM to shut down day care Faculty senate reinstates EYE requirement for incoming eshmen Ma Dodge Executive Editor At last Fridays monthly meet- ing, the USM Faculty Senate voted to reinstate the Entry Year Experience (EYE) requirement for next year’s crop of incoming freshmen. This reverses the deci- sion made by the senate during its Dec 5th meeting, when they agreed to postpone the require- ment until 2010. EYE courses were introduced three years ago, and were con- ceived as an interdisciplinary introduction to higher education. With topics ranging from “HIV/ AIDS: Science, Society, and Politics” to “Shopping: American Consumerism,” EYE classes draw from different areas of study and give freshmen a taste of what college has to offer. Faculty Senate Chair Tom Parchman called for a second pass at the proposal, which had passed 16-7 in the December. -

Pacific Design Center Hollywood Ca | November 15Th at 6Pm

WE ALL HAVE A VOICE. CELEBRATE IT. 2nd Annual GALA PACIFIC DESIGN CENTER HOLLYWOOD CA | NOVEMBER 15TH AT 6PM © 2015 Society of Voice Arts And Sciences™ HBO proudly To the Voice Arts Community: supports By community, I refer to all the people who collaborate in one form or the SOCIETY OF VOICE another to bring about the work that sustains our livelihoods and sense of ™ accomplishment. The voice arts community is the hub around which we all ARTS & SCIENCES come together. Anything can happen at this intersection and all of us can help determine the outcome. and congratulates We are not simply spectators of the industry, watching it take shape around this year’s nominees us. We are the shapers, actively breathing new life into its ever-changing form. We do this by bringing our best selves to the process with the intention of attending to the work with professionalism, respect, creativity and the spirit of collaboration, so that we may all enjoy gainful employment. I am thrilled to be a part of the magic that is the Voice Arts® Awards. It is an enchanted world of acknowledgment and encouragement and it honors the best in all of us. It is not about being better than someone else. It is about being your best. Tonight we celebrate our esteemed jurors. We celebrate the entrants, nominees and the soon to be named recipients of the top honor. This is our night. Sincerely, Rudy Gaskins Chairman & CEO Society of Voice Arts and Sciences™ ©2015 Home Box Office, Inc. All rights reserved. 3 HBO® and related channels and service marks are the property of Home Box Office, Inc. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Michael White

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Michael White Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: White, Michael G. Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Michael White, Dates: June 7, 2010 Bulk Dates: 2010 Physical 9 uncompressed MOV digital video files (4:27:02). Description: Abstract: Jazz musician and music professor Michael White (1954 - ) was professor of Spanish and African American music at Xavier University of Louisiana, and bandleader of the Original Liberty Jazz Band in New Orleans, Louisiana. White was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on June 7, 2010, in New Orleans, Louisiana. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2010_041 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Music professor and jazz musician Michael White was born on November 29, 1954 in New Orleans, Louisiana. Descended from early jazz notables such as bassist Papa John Joseph and clarinetist Willie “Kaiser” Joseph, White did not know of his background, but saw his aunt, who played classical clarinet, as his influence. White too played clarinet in the noted St. Augustine’s High School Marching Band and took private lessons from the band’s esteemed director, Lionel Hampton, for three years. White balanced school with his interest in the clarinet. He went on to obtain his B.A. degree from Xavier University in 1976 and his M.A. degree in Spanish from Tulane University in 1979. That same year, White joined the Young Tuxedo Brass Band, and two years later, White founded The Original Liberty Jazz Band with the aim of preserving the musical heritage of New Orleans.