Dying Is Hard to Do

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The AMBER Advocate

The AMBER Advocate Volume 1, issue 3. September 2007 Cheers and tears mark 2007 National Missing Children’s Day Ceremony America’s Missing: Broadcast Emergency Response U.S. Attorney General joins victims to honor AMBER Alert heroes Inside this issue: Though she is young, Tamara Brooks took the “What About AMBER awards 2 stage with the poise of a seasoned politician. Me?” on page 6) From the frontlines 4 The California college student was in Washing- ton D.C. for the 2007 National Missing Children’s "Words pay no Canadian corner 5 Day ceremony. Five years earlier, she and a debts." National high school friend learned firsthand what it was AMBER Alert Personality profile 5 like to be missing—both were kidnapped at gun- Coordinator Re- New guide 6 point. gina B. Schofield said quoting Regina B. Schofield (left) Na- Ham Radio and AMBER 7 “Emotions were laced with terror as the reality tional AMBER Alert Coordina- Shakespeare to of death went through our minds,” she said. tor, Assistant Attorney Gen- express her grati- Odds and ends 8 “We were not ready to die. Instead of giving eral, Office of Justice Programs tude to the peo- and Tamara Brooks, abduction up, we fought back with the same courage and survivor ple who have strength embodying all those who tirelessly made out- dedicate their lives to the eradication and pre- standing contributions to the AMBER Alert pro- vention of missing chil- gram. "We owe these people our gratitude. In dren.” one way or another these people have per- formed a great service on behalf of our nation's Child abduction victims children," she added. -

Revival Addresses

Revival Addresses Author(s): Torrey, Reuben Archer (1856-1928) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: R.A. Torrey is one of the greatest American evangelists. Of- ten mentioned in concert with Dwight L. Moody (of the Moody Bible Institute), Torrey spent his life (1856-1928) traveling the world (Great Britain, China, Japan, Australia, India) and spreading the gospel of Christ. Revival Addresses is a com- pilation of 40 sermons he preached at rallies around the world. If one is daunted by the sheer volume of the mes- sages, "The Greatest Sentence Ever Written" is a good place to start. It focuses on 1 John 4:8, "God is love." This simple sentence inspires some of Torrey©s most powerful messages of hope and love for the unsaved. Primarily a collection of sermons designed to bring unbelievers to salvation, Revival Addresses is a masterful resource for pastors, but also for unbelievers or Christians looking for motivation for evangel- ism. Abby Zwart CCEL Staff Writer Subjects: Practical theology Evangelism. Revivals i Contents Note 1 Title Page 2 CONTENT PAGE 3 INTRODUCTION 4 REVIVAL ADDRESSES 5 I. GOD 6 I. GOD IS 7 II. GOD IS GREAT 10 III. GOD IS HOLY. 11 IV. WE MUST ALL MEET GOD. 12 II. THE GREATEST SENTENCE THAT WAS EVER WRITTEN 13 III. FOUND WANTING 20 IV. THE JUDGMENT DAY 30 V. EVERY MAN'S NEED OF A REFUGE 37 VI. THE DRAMA OF LIFE IN THREE ACTS 45 ACT I.-WANDERING; OR THE NATURE OF SIN 46 ACT II.-DESOLATION; OR, THE FRUITS OF SIN. -

SHAR the Play

The FBI and the Bag Lady by Faye Girsh An original play in honor of Sharlotte Hydorn, known as The Bag Lady. She made Exit Bags and was visited by the FBI. This is in memory of her courage and dedication to the right to choose to die with dignity. CAST A COUPLE, the Walkers SHAR, tall, attractive, warm, vivacious 91 year old woman RAJA (PACO), foreign-looking 57 year old man, slight accent FBI AGENT(S), tough, armed, uniformed, authoritative JUDGE, compassionate but deliberate, firm BAILIFF, business like LAWYER, on Shar’s side but quiet REPORTERS ACT ONE Scene I (A couple, the Walkers, on their deck, in La Jolla.) HE: Nice evening. Shall we have our drinks outside. SHE: Good idea. Then you can tell me how your visit went with Howie and Greta. HE: (Brings wine and glasses. Pours) I’m anxious to talk to you about that. It was depressing to see what’s happening to Howie — and how hard it is for Greta. But it made me think that we should start talking about these things. SHE: What things? HE: Sickness, dying, losing one’s mind. Howie is getting more confused. It’s hard for Greta to take him anywhere. They saw a doctor last week who thought he had some form of early dementia and advised more tests. Greta feels she can’t leave him alone, and even when he’s home he often leaves and wanders off. SHE: They’re such a wonderful, devoted couple — this is a real tragedy for both of them. -

From “Michael” by William Wordsworth

1 For the delight of a few natural hearts; And, with yet fonder feeling, for the sake Of youthful Poets, who among these hills Will be my second self when I am gone. From “Michael” by William Wordsworth 2 Prose For me, a page of good prose is where one hears the rain and the noise of battle. It has the power to give grief or universality that lends it a youthful beauty. John Cheever 3 Honorable Mention – Jaedyn Johnson Karin Orchard – Daniel Boone High School The House The palms of my hands sweated heavily as my friend and I stood in a line of at least fifty people. I was anxious, and my face grew pale as loud blood curdling screams echoed through the trees. ‘Twas the night before Halloween and I somehow ended up standing in the line of the scariest haunted house in my city. The fear of faces jumping out at me and the terrifying laughs that seemed to play at my emotions gobbled up my insides. The other thing that made my skin crawl was that the haunted house was in the middle of nowhere. It was as if we were in an actual horror movie. Fog surrounded the house as if it were some blanket that kept the house warm. Although, there were no warm feelings coming from that house. I could tell it was staring at me, eyes as glowing green windows and a mouth of two unwelcoming wooden doors. The paint job of the house was a horrific brown color and the smell was musty as if I were in some swamp. -

Master's Project: Tending to Joy Karen Leu the University of Vermont

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Rubenstein School Leadership for Sustainability Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Project Publications Resources 2018 Master's Project: Tending to Joy Karen Leu The University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/rslspp Recommended Citation Leu, Karen, "Master's Project: Tending to Joy" (2018). Rubenstein School Leadership for Sustainability Project Publications. 11. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/rslspp/11 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Rubenstein School Leadership for Sustainability Project Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tending to Joy A Master’s Project Presented by Karen Leu to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Specializing in Natural Resources with a concentration in Leadership for Sustainability October, 2018 Defense Date: August 20, 2018 Project Committee: Matthew Kolan, Ph.D., Advisor Kaylynn Sullivan TwoTrees, Professional Affiliate Shadiin Garcia, Ph.D., Professional Affiliate ABSTRACT If we dare to hope for the thriving of humans and all of life, then joy must hold a solid place in our imagination. The purpose of this project was to breathe joy into my own life and into the world around me. Following a literature review, I carried out three mini-projects – creating crowd-sourced collages out of what brings people joy, sending daily text messages with quotes about joy, and providing cookies to groups working on social change efforts. -

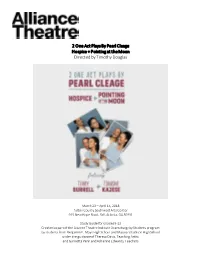

2 One Act Plays by Pearl Cleage Hospice + Pointing at the Moon Directed by Timothy Douglas

2 One Act Plays By Pearl Cleage Hospice + Pointing at the Moon Directed by Timothy Douglas March 23 – April 15, 2018 Fulton County Southwest Arts Center 915 New Hope Road, SW, Atlanta, GA 30331 Study Guide for Grades 9-12 Created as part of the Alliance Theatre Institute Dramaturgy by Students program by students from Benjamin E. Mays High School and Maynard Jackson High School under the guidance of Theresa Davis, Teaching Artist and Garnetta Penn and Adrienne Edwards, Teachers Table of Contents The Playwright: Pearl Cleage………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..page 2 Hospice + Pointing at the Moon: Curriculum Connections ………….……………………………………………………………….page 3 Section I: Hospice Hospice: Synopsis………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...page 4 Hospice: Pre- and Post-Show Discussion Questions…………………………………………………………………………………… page 4 Hospice: Written Response Prompts…………………………………………………………………………………………………………… page 5 Hospice: Characterization Graphic Organizer..................................................................................................... page 6 Hospice: Historical Figures……………………………….…………………………………………………………………………….…………….pages 7-10 Hospice: Historical Events and Places……………………………………………………………………………………………………..….. page 11 Hospice: Vocabulary …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….page 12 Hospice: Works Cited…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...page 13 Section II: Pointing at the Moon Pointing at the Moon: Synopsis……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………page 14 Pointing at the -

Party Tunes Dj Service Artist Title 112 Dance with Me 112 It's Over Now 112 Peaches & Cream

Party Tunes Dj Service www.partytunesdjservice.com Artist Title 112 Dance With Me 112 It's Over Now 112 Peaches & Cream 112 Peaches & Cream (feat. P. Diddy) 112 U Already Know 213 Groupie Love 311 All Mixed Up 311 Amber 311 Creatures 311 It's Alright [Album Version] 311 Love Song 311 You Wouldn't Believe 702 Steelo [Album Edit] $th Ave Jones Fallin' (r)/M/A/R/R/S Pump Up the Volume (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Ame iro Rondo (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Chance Chase Classroom (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Creme Brule no Tsukurikata (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Duty of love (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Eyecatch (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Great escape (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Happy Monday (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Hey! You are lucky girl (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Kanchigai Hour (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Kaze wo Kiite (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Ki Me Ze Fi Fu (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Kitchen In The Dark (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Kotori no Etude (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Lost my pieces (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari love on the balloon (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Magic of love (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Monochrome set (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Morning Glory (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Next Mission (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Onna no Ko no Kimochi (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Psychocandy (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari READY STEADY GO! (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Small Heaven (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Sora iro no Houkago (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Startup (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Tears of dragon (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Tiger VS Dragon (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Todoka nai Tegami (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Yasashisa no Ashioto (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Yuugure no Yakusoku (ToraDora!) Horie Yui Vanilla Salt (TV-SIZE) (ToraDora!) Kugimiya Rie, Kitamura Eri & Horie Yui Pre-Parade (TV-SIZE) .38 Special Hold on Loosely 1 Giant Leap f. -

Call of Duty®: Black Ops Escalation Available Now on Playstation®3 System

Call of Duty®: Black Ops Escalation Available Now On PlayStation®3 System SANTA MONICA, Calif., June 10, 2011 /PRNewswire/ -- Call of Duty®: Black Ops Escalation, the latest content pack from the record-setting Call of Duty®: Black Ops is now available on the PlayStation®3 computer entertainment system. Escalation features four new multiplayer maps and an unprecedented Zombie experience, including famed director George A. Romero, Robert Englund, Sarah Michelle Gellar, Michael Rooker and Danny Trejo, as well as an original music track from Avenged Sevenfold titled "Not Ready to Die." The Escalation content pack's new multiplayer maps include: ● "Hotel," where players battle it out on the roof of a Cuban luxury hotel and casino against the vivid backdrop of old Havana ● "Convoy," which delivers intense, close-quarters combat at the scene of an ambushed U.S. military convoy ● "Zoo," which sets gamers on an eerie ride through an abandoned Soviet Russian Zoo with danger at every turn ● "Stockpile," which pits players in a remote Russian farm town, housing secret WMD facilities ● "Call of the Dead," Escalation's Zombie experience that assembles a zombie-carnage dream team to fight against a new and undefeatable zombie horde menace, all set in the dark, ice-covered isles of Siberia "For the millions of dedicated fans playing Black Ops each and every day online around the world, we crafted for them unique multiplayer maps and experiences with Escalation, that will allow PS3 players to continue enjoying the game for a long time to come," said Treyarch Studio Head, Mark Lamia. "And with Call of the Dead, we went all out to give our loyal Zombie fans a totally new creative to enjoy." Call of Duty: Black Ops Escalation can be downloaded for $14.99 from the PlayStation®Store for PlayStation 3 system. -

December 16 December 23

DECEMBER 16 ISSUE DECEMBER 23 Orders Due November 18 26 Orders Due November 25 axis.wmg.com 12/16/16 AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP ARTIST TITLE LBL CNF UPC SEL # SRP ORDERS DUE Disturbed-Live at Red Rocks Disturbed REP A 093624915478 557998 29.98 11/18/16 (Explicit)(2LP) Garcia, Angelica Medicine for Birds (Vinyl) WB A 093624915607 557037 27.98 11/18/16 Morgan, William Michael Vinyl (Vinyl) WNS A 093624915485 557289 19.98 11/18/16 Panic! At The Disco A Fever You Can’t Sweat Out (Vinyl) FBY A 075678667626 552015 19.98 11/18/16 Come What(ever) May (10th Anniversary Stone Sour Edition)(Explicit)(2LP Gold & Black Vinyl RRR A 016861807313 180731 29.98 11/18/16 w/Digital Download) Last Update: 02/26/16 For the latest up to date info on this release visit axis.wmg.com. ARTIST: Disturbed TITLE: Disturbed-Live at Red Rocks (Explicit)(2LP) Label: REP/Reprise Config & Selection #: A 557998 Street Date: 12/16/16 Order Due Date: 11/18/16 UPC: 093624915478 OTHER EDITIONS Box Count: 30 Unit Per Set: 2 CD 557998 Explicit SRP: $29.98 ($18.98) Alphabetize Under: D ALBUM FACTS Genre: Rock CD 558489 Edited ($18.98) Description: Live at Red Rocks captures Disturbed's August 15, 2016 show at the fabled Colorado amphitheater where the band stopped during their tour in support of current album Immortalized, which has been certified Gold. The album features songs spanning Disturbed's 20-year-career, including Mainstream Rock chart hits "Down With The Sickness," "Stricken," "Inside the Fire," "Indestructible," "The Vengeful One," "The Light," and their now Platinum-certified version of Simon & Garfunkel's classic hit "The Sound of Silence." ARTIST & INFO Hometown: Chicago, IL After a four year hiatus, Grammy Award-nominated, multiplatinum hard rock titans Disturbed returned with their sixth studio album, Immortalized, the group's fifth to debut at #1 on the Billboard Top 200, a rare distinction only achieved by one other hard rock band in the history of the chart: Metallica. -

Spring 1992 Womanthought Vol

Lesley University DigitalCommons@Lesley Commonthought Lesley University Student Publications Spring 1992 Womanthought Vol. III, No. I (Spring 1992) Womanthought Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/commonthought Part of the Fine Arts Commons, Illustration Commons, Photography Commons, Poetry Commons, and the Printmaking Commons Recommended Citation Womanthought Staff, "Womanthought Vol. III, No. I (Spring 1992)" (1992). Commonthought. 25. https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/commonthought/25 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Lesley University Student Publications at DigitalCommons@Lesley. It has been accepted for inclusion in Commonthought by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Lesley. For more information, please contact [email protected]. w WOMANTHOUGHT Magazine of the Arts at Lesley College Volume III, No. 1 Editor-in-Chief Jennifer Hill Assistant Editors Amanda McNuge Tracy Wright Art Editor Stephanie Krauss Fiction Editor Rebecca Drey Poetry Editor Edy Shapiro Business Manager Bharati Samnani Sales Manager Caryn Mayo Typists Judith Periale Bryson Dean Layout Artist Bryson Dean Faculty Saint Dr. Pluto STAFF MEMBERS Elizabeth Carp Beth Coates Marianna Geary Kate Huston SPECIAL THANKS TO: President Margaret McKenna Dean Clauszell Smith Dean Carol Streit Dr. Stephen Trainor Dr. Carolyn Wyatt Office of Student Affairs Jennifer Kilson-Page needs yo r work ... Still accepting submissions until December 6, 1 Sports Fiction: up to 7 pages Poetry about chicks: up to S pages Art: black and white photos, Letter From the Editor drawings or prints Send work with an SASE to: -AnnePluto 29Mellen St.Cainbrid e NIA 02138 349- First and foremost, I would like to thank the staff of Womanthought. -

Univerzitet U Beogradu Master Rad: Slika Hladnoratovskog I Posthladnoratovskog Sveta U Hevi Metal Muzici (1970-2017)

Univerzitet u Beogradu Filozofski fakultet Odeljenje za istoriju Master rad: Slika hladnoratovskog i posthladnoratovskog sveta u hevi metal muzici (1970-2017) Kandidat: Miloš Čabraja Mentor: prof. dr Radina Vučetić IS -16/27 Beograd, septembar, 2019 Sadržaj Predgovor .............................................................................................................................................. 1 Uvod ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 Hladnoratovske krize u hevi metalu (1970-1991) ................................................................................. 7 Strah od nuklearne apokalipse u hevi metalu (1970-2017) ................................................................ 13 Nuklearna histerija u Hladnom ratu 1970-ih i 1980-ih ........................................................................ 15 Nuklearna histerija u Zalivskom ratu i posthladnoratovskom periodu (1990-2017) ............................ 26 Uticaj stripa i filma na nuklearnu histeriju u hevi metalu .................................................................... 30 Biohemijska paranoja i antropoceno doba u hevi metalu (1980-2017) .............................................. 36 Proliferacija biohemijskog naoružanja 1980-ih ................................................................................... 36 Strah od laboratorijskih virusa i epidemija AIDS-a u hevi metalu ....................................................... -

Bo2 Zombies Hack Xbox 360 Zombie Cheats for Cod Black Ops with an Xbox

bo2 zombies hack xbox 360 Zombie Cheats for Cod Black Ops with an Xbox. Call Of Duty: Black Ops Zombies Glitches: Working Kino Der Toten Glitches (2018) If you enjoyed this video, please like and subscribe! Songs: 1. Eddy B & Tim Gunter Young Superstars. 2. Skizzy Mars Changes. Twitter @bluemonster1231. https://twitter.com/bluemonster1231. Video taken from the channel: BlueMonsterFTL. Call of Duty Black Ops Zombies Cheat Codes Kino der Toten. Drop a like and subscribe fore more awesome content. Video taken from the channel: Elared gaming. Call Of DutyBlack Ops Cheats Zombie for Xbox 360. Video taken from the channel: wwe123520. Call of Duty: Black Ops Hidden Menu Secret and Computer Codes Mini-Games and Cheats. Slammerama from GamingDrunk.com shows how to get out of the chair in the menu of the game Call of Duty: Black Ops. Also shows the different cheats and mini-games available at the computer in the interrogation room.. Please go to http://gamingdrunk.com/articles/hidden-menu-secrets- and-computer-codes-unlock-mini-games-maps-and-cheats-call-duty-black-op for any questions/comments about the video or the game. Video taken from the channel: DrGh0st. How to Unlock the Ray Gun in Black Ops Multiplayer. Getting sick of those fake tutorials on how to get a Ray Gun in multiplayer? Well try this tutorial, I ensure you’ll end up getting one! By the way, this video is a fake, but I know most people won’t see this piece of information!:P. For those who have seen this small piece of information, feel free to laugh at the majority who cannot read the description.