British Labour and the Confederacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diplomacy and the American Civil War: the Impact on Anglo- American Relations

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses, 2020-current The Graduate School 5-8-2020 Diplomacy and the American Civil War: The impact on Anglo- American relations Johnathan Seitz Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/masters202029 Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Seitz, Johnathan, "Diplomacy and the American Civil War: The impact on Anglo-American relations" (2020). Masters Theses, 2020-current. 56. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/masters202029/56 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses, 2020-current by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Diplomacy and the American Civil War: The Impact on Anglo-American Relations Johnathan Bryant Seitz A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History May 2020 FACULTY COMMITTEE: Committee Chair: Dr. Steven Guerrier Committee Members/ Readers: Dr. David Dillard Dr. John Butt Table of Contents List of Figures..................................................................................................................iii Abstract............................................................................................................................iv Introduction.......................................................................................................................1 -

Kaltz Text Final Eingebettet

Fremdsprachen in Geschichte und Gegenwart Herausgegeben von Helmut Glück und Konrad Schröder Band 11,1 2013 Harrassowitz Verlag . Wiesbaden Paul Lévy Die deutsche Sprache in Frankreich Band 1: Von den Anfängen bis 1830 Aus dem Französischen übersetzt und bearbeitet von Barbara Kaltz 2013 Harrassowitz Verlag . Wiesbaden Gedruckt mit freundlicher Unterstützung der Stiftung Deutsche Sprache. Wissenschaftlicher Beirat: Csaba Földes, Mark Häberlein, Hilmar Hoffmann, Barbara Kaltz, Jochen Pleines, Libuše Špácˇilová, Harald Weinrich, Vibeke Winge. Titel der frz. Originalausgabe: Paul Lévy, La Langue allemande en France. Pénétration et diffusion des origines à nos jours: IAC, Lyon-Paris 1950-1952. Abbildung auf dem Umschlag: Straßburg um 1750 © akg-images. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the internet at http://dnb.dnb.de Informationen zum Verlagsprogramm finden Sie unter http://www.harrassowitz-verlag.de © Otto Harrassowitz GmbH & Co. KG, Wiesbaden 2013 Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist ohne Zustimmung des Verlages -

Foreword Introduction: Ł'orient N'existe

Notes Foreword 1. John Jay Chapman, Practical Agitation, New York: Charles Scribner & Sons 1900, pp. 63–64. 2. See Walter Lippman, Public Opinion, Charleston: BiblioLife 2008. 3. When, in the Summer of 2013, Western European states grounded Evo Morales’ presidential plane on which he was returning from Moscow to Bolivia, suspecting that Edward Snowden was hidden in it on his way to the Bolivian exile, the most humiliating aspect was the Europeans’ attempt to retain their dignity: instead of openly admitting that they were acting under US pressure, or pretending that they were simply following the law, they jus- tified the grounding on pure technicalities, claiming that the flight was not properly registered in their air traffic control. The effect was miserable—the Europeans not only appeared as US servants, they even wanted to cover up their servitude with ridiculous technicalities. Introduction: Ł’Orient n’existe pas 1. The direct result of the 2002 Patriot Act was the 779 detainees in Guantanamo, most of them Muslim and many of them non-combatants, without any access to counsel or habeas corpus, against all international conventions (Chossudovsky 2004). Some of these people allegedly committed sui- cide. Despite President Obama’s promises during both his campaigns, the Guantanamo Camp is still open and functioning. 2. It is not a mere coincidence that Herbert’s Dune (1965) became, almost 50 years later, a perfect, prophetic and almost allegorical metaphor for the Orient subverting the existence of the ‘Empire’, another Lacanian letter eventually arriving at its destination. 3. The same process in the Americas, Australia and New Zealand, although similar in certain respects, is outside the scope of this study. -

Propaganda Use by the Union and Confederacy in Great Britain During the American Civil War, 1861-1862 Annalise Policicchio

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Duquesne University: Digital Commons Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Summer 2012 Propaganda Use by the Union and Confederacy in Great Britain during the American Civil War, 1861-1862 Annalise Policicchio Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Policicchio, A. (2012). Propaganda Use by the Union and Confederacy in Great Britain during the American Civil War, 1861-1862 (Master's thesis, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1053 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PROPAGANDA USE BY THE UNION AND CONFEDERACY IN GREAT BRITAIN DURING THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR, 1861-1862 A Thesis Submitted to the McAnulty College & Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for The Degree of Masters of History By Annalise L. Policicchio August 2012 Copyright by Annalise L. Policicchio 2012 PROPAGANDA USE BY THE UNION AND CONFEDERACY IN GREAT BRITAIN DURING THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR, 1861-1862 By Annalise L. Policicchio Approved May 2012 ____________________________ ______________________________ Holly Mayer, Ph.D. Perry Blatz, Ph.D. Associate Professor of History Associate Professor of History Thesis Director Thesis Reader ____________________________ ______________________________ James C. Swindal, Ph.D. Holly Mayer, Ph.D. Dean, McAnulty College & Graduate Chair, Department of History School of Liberal Arts iii ABSTRACT PROPAGANDA USE BY THE UNION AND CONFEDERACY IN GREAT BRITAIN DURING THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR, 1861-1862 By Annalise L. -

Herbert J. Doherty, Jr

Florida Historical Quarterly Volume 31 Issue 3 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 31, Article 1 Issue 3 1952 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 31, Issue 3 Florida Historical Society [email protected] Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Historical Quarterly by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Society, Florida Historical (1952) "Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 31, Issue 3," Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 31 : Iss. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol31/iss3/1 Society: Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 31, Issue 3 Volume XXXI January, 1953 Number 3 The FLORIDA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY CONTENTS R. K. Call vs. the Federal Government on the Seminole War Herbert J. Doherty, Jr. The Railroad Background of the Florida Senatorial Election of 1851 Arthur W. Thompson De Soto and Terra Ceia John R. Swanton An Educator Looks at Florida in 1884 A letter of Ashley D. Hurt Samuel Proctor (ed.) John Batterson Stetson, Jr., 1884-1952 Book Review: Hotze, “Three Months in the Confederate Army” Bell Irvin Wiley Regional and local historical societies: Jacksonville Historical Society St. Petersburg Historical Society Historical Association of Southern Florida Pensacola Historical Society St. Lucie County Historical Society Hillsborough County Historical Commission County Museums The Florida Historical Society The Annual Meeting New Members Membership roll of the Society Contributors to this number SUBSCRIPTION FOUR DOLLARS SINGLE COPIES ONE DOLLAR (Copyright, 1953, by the Florida Historical Society. -

A Study of Thomas Butler King, Commissioner of Georgia to Europe, 1861

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Summer 2006 Secession Diplomacy: A Study of Thomas Butler King, Commissioner of Georgia to Europe, 1861 Mary Pinckney Kearns Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Recommended Citation Kearns, Mary Pinckney, "Secession Diplomacy: A Study of Thomas Butler King, Commissioner of Georgia to Europe, 1861" (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 587. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/587 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SECESSIONDIPLOMACY:ASTUDYOFTHOMASBUTLERKING, COMMISSIONEROFGEORGIATOEUROPE,1861 by MARYPINCKNEYKEARNS (UndertheDirectionofDonaldRakestraw) ABSTRACT Theobjectiveofthisthesisistodeterminethefunctionandeffectivenessofstate diplomatsintheConfederatecauseabroadbyexaminingthemissionofThomasButler KingtothecourtsofEuropeforthestateofGeorgiawithinthecontextofthe internationaldimensionsofthefirstyearoftheCivilWar.Theworkwilladdressthe variousConfederateargumentsforrecognitionthroughtheexaminationofpropaganda documentspublishedbyKingandtheireffectonFrenchandBritishpolicies.Thework willfurtherinvestigatethedirecttrademovementofthe1850sanditseffectsonthe -

The Emperor Has No Clothes

THE EMPEROR HAS NO CLOTHES How Hubris, Economics, Bad Timing and Slavery Sank King Cotton Diplomacy with England Joan Thompson Senior Division Individual Paper Thompson 1 All you need in this life is ignorance and confidence, and then the success is sure. -Mark Twain DISASTROUS OVERCONFIDENCE 1 The ancient Greeks viewed hubris as a character flaw that, left unrecognized, caused personal destruction. What is true for a person may be true for a people. For the Confederate States of America, excessive faith in cotton, both its economic and cultural aspects, contributed mightily to its entry into, and ultimate loss of, the Civil War. The eleven states that seceded from the Union viewed British support as both a necessity for Southern success and a certainty, given the Confederacy’s status as the largest (by far) supplier of cotton to Britain. Yet, there was a huge surplus of cotton in Britain when the war began. Moreover, cotton culture’s reliance on slavery presented an insurmountable moral barrier. Southern over-confidence and its strong twin beliefs in the plantation culture and the power of cotton, in the face of countervailing moral values and basic economic laws, blinded the Confederacy to the folly of King Cotton diplomacy. THE CONFLICT: KING COTTON AND SLAVERY Well before the bombardment of Fort Sumter, the South exhibited deep confidence in cotton’s economic power abroad. During the Bloody Kansas debate,2 South Carolina senator James Henry Hammond boasted, “in [the South] lies the great valley of Mississippi…soon to be 1 excessive pride 2 In 1858, Congress debated whether Kansas should be admitted into the Union as a free state or slave state. -

Les Sudistes Et La Race Aryenne

LES SUDISTES ET LA RACE ARYENNE Serge Noirsain Le concept de race aryenne émane de l’écrivain français Arthur de Gobineau (1816- 1882) qui l'introduisit en 1853 dans son Essai sur l'inégalité des races humaines. Avec ce livre, Gobineau inventa le grand mythe la race aryenne. En 1856, commandité par Josiah C. Nott (1804-1873), le journaliste sudiste Henry Hotze se fit connaître dans le Sud par son adaptation, en anglais, de l'ouvrage de Gobineau : The Moral and Intellectual Diversity of Races. A la veille de la guerre civile, Nott passait pour une sommité dans le monde médical sudiste. Après avoir étudié à l’Institut de Médecine et de Chirurgie de New York, il obtient son diplôme à l’Université de Pennsylvanie en 1827, y enseigne pendant deux ans puis pratique la médecine en Caroline du Sud jusqu’en 1835. Ensuite, il complète ses études à Paris avant d’ouvrir un cabinet à Mobile, en Alabama. Sa notoriété lui ouvre un poste de professeur d’anatomie à l’Université de Louisiane en 1857. L’année suivante, lui et quelques confrères fondent le Collège médical de l’Alabama. Dans le même temps, il commit une série d’ouvrages relatifs aux races et à l’ethnologie : Two Lectures on the Connection between the Biblical and Physical History of Man, New York, 1849 ; The Negro Race : Its Ethnology and History, et The Physical History of the Jewish Race, tous deux à Charleston en 1850. Fervents adeptes du polygénisme, Nott et George Gliddon publient en 1854 : Types of Mankind or Ethnological Researches based upon Ancient Monuments, Paintings, Sculptures and Crania of Races, and upon their natural, geographical, philosophical et biblical history et Indigenous Races of the Earth or New Chapters of Ethnological Inquiry en 1857. -

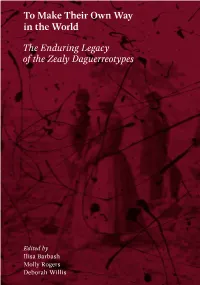

To Make Their Own Way in the World

To Make Their Own Way in the World The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes Edited by Ilisa Barbash Molly Rogers Deborah Willis 020 PRESIDENT AND FELLOWS OF HARVARD COLLEGE COPYRIGHT © 2 To Make Their Own Way in the World The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes Edited by Ilisa Barbash Molly Rogers Deborah Willis With a foreword by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. COPYRIGHT © 2020 PRESIDENT AND FELLOWS OF HARVARD COLLEGE Contents 9 Foreword by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. 15 Preface by Jane Pickering 17 Introduction by Molly Rogers 25 Gallery: The Zealy Daguerreotypes Part I. Photographic Subjects Chapter 1 61 This Intricate Question The “American School” of Ethnology and the Zealy Daguerreotypes by Molly Rogers Chapter 2 71 The Life and Times of Alfred, Delia, Drana, Fassena, Jack, Jem, and Renty by Gregg Hecimovich Chapter 3 119 History in the Face of Slavery A Family Portrait by Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham Chapter 4 151 Portraits of Endurance Enslaved People and Vernacular Photography in the Antebellum South by Matthew Fox-Amato COPYRIGHT © 2020 PRESIDENT AND FELLOWS OF HARVARD COLLEGE Part II. Photographic Practice Chapter 5 169 The Curious Art and Science of the Daguerreotype by John Wood Chapter 6 187 Business as Usual? Scientific Operations in the Early Photographic Studio by Tanya Sheehan Chapter 7 205 Mr. Agassiz’s “Photographic Saloon” by Christoph Irmscher Part III. Ideas and Histories Chapter 8 235 Of Scientific Racists and Black Abolitionists The Forgotten Debate over Slavery and Race by Manisha Sinha Chapter 9 259 “Nowhere Else” South Carolina’s Role in a Continuing Tragedy by Harlan Greene Chapter 10 279 “Not Suitable for Public Notice” Agassiz’s Evidence by John Stauffer Chapter 11 297 The Insistent Reveal Louis Agassiz, Joseph T. -

Civil War Manuscripts

CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS MANUSCRIPT READING ROW '•'" -"•••-' -'- J+l. MANUSCRIPT READING ROOM CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS A Guide to Collections in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress Compiled by John R. Sellers LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON 1986 Cover: Ulysses S. Grant Title page: Benjamin F. Butler, Montgomery C. Meigs, Joseph Hooker, and David D. Porter Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Library of Congress. Manuscript Division. Civil War manuscripts. Includes index. Supt. of Docs, no.: LC 42:C49 1. United States—History—Civil War, 1861-1865— Manuscripts—Catalogs. 2. United States—History— Civil War, 1861-1865—Sources—Bibliography—Catalogs. 3. Library of Congress. Manuscript Division—Catalogs. I. Sellers, John R. II. Title. Z1242.L48 1986 [E468] 016.9737 81-607105 ISBN 0-8444-0381-4 The portraits in this guide were reproduced from a photograph album in the James Wadsworth family papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. The album contains nearly 200 original photographs (numbered sequentially at the top), most of which were autographed by their subjects. The photo- graphs were collected by John Hay, an author and statesman who was Lin- coln's private secretary from 1860 to 1865. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402. PREFACE To Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War was essentially a people's contest over the maintenance of a government dedi- cated to the elevation of man and the right of every citizen to an unfettered start in the race of life. President Lincoln believed that most Americans understood this, for he liked to boast that while large numbers of Army and Navy officers had resigned their commissions to take up arms against the government, not one common soldier or sailor was known to have deserted his post to fight for the Confederacy. -

Civil War Book Review Annotations

Civil War Book Review Spring 2005 Article 30 Annotations CWBR_Editor Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation CWBR_Editor (2005) "Annotations," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 7 : Iss. 2 . Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol7/iss2/30 CWBR_Editor: Annotations ANNOTATIONS Morrow Jr., Robert F. Spring 2005 Morrow Jr., Robert F. 77th New York Volunteers: "Sojering" in the VI Corps. White Mane, $29.95 ISBN 1572493526 The volunteers of the 77th New York participated in over 50 battles including Antietam, Gettysburg, and the surrender at Appomattox. This book narrates the regiment's admirable service from its recruitment to the reunions held for its survivors many years after the war. Allen, Frederick Spring 2005 Allen, Frederick A Decent Orderly Lynching: The Montana Vigilantes. University of Oklahoma Press, $34.95 ISBN 806136375 During the early weeks of 1864, in the goldmining towns of southwest Montana, vigilantes hanged more than 21 men including a corrupt sheriff. Frederick Allen tells the story of how the region's crude justice system became uncontrollable and resulted in the lynching of even more men, some of whom were not guilty of a crime. Griffin, John Chandler Spring 2005 Griffin, John Chandler A Pictorial History of the Confederacy. McFarland & Company, $49.95 ISBN 786417447 Relying on photographs, paintings, sketches, and maps, this 228 page book chronicles the rise and fall of the Confederacy and its leaders, troops, and major battles. Published by LSU Digital Commons, 2005 1 Civil War Book Review, Vol. 7, Iss. 2 [2005], Art. 30 Higgins, Billy D. Spring 2005 Higgins, Billy D. -

Geschichte Neuerwerbungsliste 1. Quartal 2009

Geschichte Neuerwerbungsliste 1. Quartal 2009 Geschichte: Allgemeines und Einführungen............................................................................................................2 Geschichtsschreibung und Geschichtstheorie ..........................................................................................................2 Teilbereiche der Geschichte (Politische Geschichte, Kultur-, Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte allgemein) ........4 Historische Hilfswissenschaften ..............................................................................................................................7 Ur- und Frühgeschichte; Mittelalter- und Neuzeitarchäologie.................................................................................8 Allgemeine Weltgeschichte, Geschichte der Entdeckungen, Geschichte der Weltkriege......................................14 Alte Geschichte......................................................................................................................................................24 Europäische Geschichte in Mittelalter und Neuzeit ...............................................................................................26 Deutsche Geschichte..............................................................................................................................................30 Geschichte der deutschen Laender und Staedte .....................................................................................................36 Geschichte der Schweiz, Österreichs, Ungarns,