The Interpersonal Functions of Empathy: a Relational Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Multimodal Attention Mechanism for Autonomous Mobile Robotics

IX WORKSHOP DE AGENTES FÍSICOS, SEPTIEMBRE 2008, VIGO A Multimodal Attention Mechanism for Autonomous Mobile Robotics Raúl Arrabales, Agapito Ledezma and Araceli Sanchis extensively applied in robotics, e.g. [2]. However, much less Abstract— Whatever the mission of an autonomous mobile effort has been put in pure multimodal attention mechanisms robot is, attention is a helpful cognitive capability when dealing [7]. Usually attention mechanisms for robots focus in great with real world environments. In this paper we present a novel degree in visual sensory information; nevertheless, some control architecture which enables an integrated and efficient salient examples incorporate data from other sensors in the filtering of multiple modality sensory information. The concept of context is introduced as the set of criteria that determines attention mechanism. For instance, laser range finders [9]. what sensory information is relevant to the current mission. In this work we present a purely multimodal attention The proposed attention mechanism uses these contexts as a mechanism, in which vision could be eventually mean to adaptively select the constrained cognitive focus of the incorporated, but has not been used for preliminary testing. robot within the vast multimodal sensory space available. This Instead, bumpers and sonar range finders have been applied. approach for artificial attention is tested in the domain of autonomous mapping. In the next sections we discuss the implementation of an Index Terms— Physical agents, Attention, cognitive attention mechanism able to fulfill the requirement of modeling, mobile robotics. selecting relevant sensorimotor information. Section II covers the definition of the attentional contexts that are used I. INTRODUCTION to form sets of sensory and motor data. -

Conflict, Arousal, and Logical Gut Feelings

CONFLICT, AROUSAL, AND LOGICAL GUT FEELINGS Wim De Neys1, 2, 3 1 ‐ CNRS, Unité 3521 LaPsyDÉ, France 2 ‐ Université Paris Descartes, Sorbonne Paris Cité, Unité 3521 LaPsyDÉ, France 3 ‐ Université de Caen Basse‐Normandie, Unité 3521 LaPsyDÉ, France Mailing address: Wim De Neys LaPsyDÉ (Unité CNRS 3521, Université Paris Descartes) Sorbonne - Labo A. Binet 46, rue Saint Jacques 75005 Paris France [email protected] ABSTRACT Although human reasoning is often biased by intuitive heuristics, recent studies on conflict detection during thinking suggest that adult reasoners detect the biased nature of their judgments. Despite their illogical response, adults seem to demonstrate a remarkable sensitivity to possible conflict between their heuristic judgment and logical or probabilistic norms. In this chapter I review the core findings and try to clarify why it makes sense to conceive this logical sensitivity as an intuitive gut feeling. CONFLICT, AROUSAL, AND LOGICAL GUT FEELINGS Imagine you’re on a game show. The host shows you two metal boxes that are both filled with $100 and $1 dollar bills. You get to draw one note out of one of the boxes. Whatever note you draw is yours to keep. The host tells you that box A contains a total of 10 bills, one of which is a $100 note. He also informs you that Box B contains 1000 bills and 99 of these are $100 notes. So box A has got one $100 bill in it while there are 99 of them hiding in box B. Which one of the boxes should you draw from to maximize your chances of winning $100? When presented with this problem a lot of people seem to have a strong intuitive preference for Box B. -

Panic Disorder Issue Brief

Panic Disorder OCTOBER | 2018 Introduction Briefings such as this one are prepared in response to petitions to add new conditions to the list of qualifying conditions for the Minnesota medical cannabis program. The intention of these briefings is to present to the Commissioner of Health, to members of the Medical Cannabis Review Panel, and to interested members of the public scientific studies of cannabis products as therapy for the petitioned condition. Brief information on the condition and its current treatment is provided to help give context to the studies. The primary focus is on clinical trials and observational studies, but for many conditions there are few of these. A selection of articles on pre-clinical studies (typically laboratory and animal model studies) will be included, especially if there are few clinical trials or observational studies. Though interpretation of surveys is usually difficult because it is unclear whether responders represent the population of interest and because of unknown validity of responses, when published in peer-reviewed journals surveys will be included for completeness. When found, published recommendations or opinions of national organizations medical organizations will be included. Searches for published clinical trials and observational studies are performed using the National Library of Medicine’s MEDLINE database using key words appropriate for the petitioned condition. Articles that appeared to be results of clinical trials, observational studies, or review articles of such studies, were accessed for examination. References in the articles were studied to identify additional articles that were not found on the initial search. This continued in an iterative fashion until no additional relevant articles were found. -

EMOTIONAL REASONING and DECISION MAKING Understanding and Regulating Emotions That Serve People’S Goals

EMOTIONAL REASONING AND DECISION MAKING Understanding and regulating emotions that serve people’s goals Paula C. Peter Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Marketing Dr. David Brinberg, Chair Dr. Eloise Coupey Dr. Kent Nakamoto Dr. Jim Jaccard April 11, 2007 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Emotional Intelligence, Decision Making, Consumer Health Copyright 2007, Paula C. Peter EMOTIONAL REASONING AND DECISION MAKING Understanding and regulating emotions that serve people’s goals Paula C. Peter (ABSTRACT) Increasing physical activity and adopting a healthy diet have the goal to enhance consumer welfare. The goal of this set of studies is to contribute to a research agenda that tries to support and enhance the life of consumers, through the exploration of emotional intelligence as a new possible avenue of research related to consumer behavior and health. Four studies are proposed that look at the possibility to introduce emotional intelligence in decision making and performance related to health (i.e. adoption and maintenance of a healthy diet/weight). The findings suggest the salient role of emotional reasoning (i.e. understanding and regulation of emotions) on decision making and performance related to health. Training on emotional intelligence and health seems to activate mechanisms that help people to use their knowledge in the right direction in order to make better decisions and improve performance related to health (i.e. adoption/maintenance of healthy diet/weight) DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to: my mom , my role model my dad , my biggest fan Alessio , my anchor iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To David Brinberg. -

Facts About EMOTIONAL REASONING

Volume 7 Issue 1 (2016) Facts about EMOTIONAL REASONING A thought is not a fact. Yet we often allow our thoughts to affect how we feel and what we do. These then affect our well-being and our relationships as in the case of Mr Tan and Jane. *Mr Tan thinks, ‘My children are beginning to talk back at me the way their mother argues with me. My wife must have taught the children to dishonour me.’ Does he have evidence to support his suspicion? No. Yet Mr Tan is angry with his wife at this thought and resents his children for learning the wrong things from their mother. Where does this thought come from if it is not based on evidence? may have birthed the thought that his wife has make better sense of our experiences influenced his children. In Jane’s case, her by better engaging our reasoning. *Jane thinks, ‘I am going to do badly in anxiety and fear of failure resulted in her From time to time, we continue to fall this examination.’ The fact is, she has thinking that she will do badly. back on emotional reasoning out of completed her revisions and could habit. We are most vulnerable to doing complete the past years’ questions. Yet More examples of such thoughts are:- so during times when we are stressed. that thought causes her sleepless nights. ‘I feel unworthy, therefore I am worthless.’ ‘I Where does that thought come from if it feel unloved therefore I am unlovable.’ ‘I feel A group of people, however, may find it is not based on fact? unappreciated therefore I am useless.’ a challenge to get out of this mode of operating psychologically. -

1 the Madness That Is the World: Young Activist's Emotional

The Madness that Is The World: Young activist’s emotional reasoning and their participation in a local Occupy movement Abstract: The focus of this paper is young people’s participation in the Occupy protest movement that emerged in the early autumn of 2011. Its concern is with the emotional dimensions of this and in particular the significance of emotions to the reasoning of young people who came to commit significant time and energy to the movement. Its starting point is the critique of emotions as narrowly subjective, whereby the passions that events like Occupy arouse are treated as beyond the scope of human reason. The rightful rejection of this reductionist argument has given rise to an interest in understandings of the emotional content of social and political protest as normatively constituted, but this paper seeks a different perspective by arguing that the emotions of Occupy activists can be regarded as a reasonable force. It does so by discussing findings from long-term qualitative research with a Local Occupy movement somewhere in England and Wales. Using the arguments of social realists, the paper explores this data to examine why things matter sufficiently for young people to care about them and how the emotional force that this involves constitutes an indispensable source of reason in young activists’ decisions to become involved in Local Occupy. Keywords: young people, emotion, social movements, Occupy, reason, reasoning In his rapid response to the international emergence of the Occupy movement, Manuel Castells (2012) begins with a lament for the categorical exclusion of individuals from studies of social movements. -

How Multidimensional Is Emotional Intelligence? Bifactor Modeling of Global and Broad Emotional Abilities of the Geneva Emotional Competence Test

Journal of Intelligence Article How Multidimensional Is Emotional Intelligence? Bifactor Modeling of Global and Broad Emotional Abilities of the Geneva Emotional Competence Test Daniel V. Simonet 1,*, Katherine E. Miller 2 , Kevin L. Askew 1, Kenneth E. Sumner 1, Marcello Mortillaro 3 and Katja Schlegel 4 1 Department of Psychology, Montclair State University, Montclair, NJ 07043, USA; [email protected] (K.L.A.); [email protected] (K.E.S.) 2 Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center, Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA; [email protected] 3 Swiss Center for Affective Sciences, University of Geneva, 1205 Geneva, Switzerland; [email protected] 4 Institute of Psychology, University of Bern, 3012 Bern, Switzerland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Drawing upon multidimensional theories of intelligence, the current paper evaluates if the Geneva Emotional Competence Test (GECo) fits within a higher-order intelligence space and if emotional intelligence (EI) branches predict distinct criteria related to adjustment and motivation. Using a combination of classical and S-1 bifactor models, we find that (a) a first-order oblique and bifactor model provide excellent and comparably fitting representation of an EI structure with self-regulatory skills operating independent of general ability, (b) residualized EI abilities uniquely Citation: Simonet, Daniel V., predict criteria over general cognitive ability as referenced by fluid intelligence, and (c) emotion Katherine E. Miller, Kevin L. Askew, recognition and regulation incrementally predict grade point average (GPA) and affective engagement Kenneth E. Sumner, Marcello Mortillaro, and Katja Schlegel. 2021. in opposing directions, after controlling for fluid general ability and the Big Five personality traits. -

Emotional Intelligence and Conflict Resolution

Emotional Intelligence and Conflict Resolution By: Fred McGrath Fred McGrath & Associates Presented at: ACLEA 49th Mid‐Year Meeting February 2‐5, 2013 Clearwater, FL Fred McGrath Fred McGrath & Associates Saint Paul, MN Fred McGrath has been designing and delivering experiential, interactive keynotes, seminars, and webinars for legal professionals and business leaders for over 20 years. His strong advocacy of inclusive, improv‐based training stems from a successful acting/screenwriting career in Hollywood. Before focusing solely on leaderships training, Fred was a busy working actor and veteran of over 100 national commercials as well as numerous co‐starring roles in network dramas and sitcoms. Always exceeding expectation with no shortage of fun and laughs, Fred engages participants on a wide variety of topics with his unique approach. Year after year, Fred continues to be one of the highest‐rated professional development trainer/coaches anywhere. “In the corporation of the future, new leaders will not be masters, but maestros. The leadership task will be to anticipate the signs of coming change, to inspire creativity, and to get the best ideas from everybody. ‐‐Ned Herrmann, author of The Creative Brain “Cognitive learning promotes improved knowledge. Experiential learning promotes improved behavior. ‐‐Fred McGrath The Advantages of Emotional Intelligence and Experiential Training Emotional Intelligence (EI), the key to improving client building, existing relationships, negotiation techniques and leadership skills, can best be taught, accessed, coached, developed and enhanced by using improvisation techniques to support emotive learning. Cognitive learning is less effective because it is knowledge‐based. As such, comprehending the concepts of EI is not enough. -

Neuroscience Impact Brain and Business

Innovation Trend Report Neuroscience Impact Brain and Business NEUROSCIENCE IMPACT – BRAIN AND BUSINESS INTRODUCTION This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- Acknowledgements NoDerivatives 4.0 International. We would like to extend a special thanks to all of the companies and To view a copy of this license, visit: individuals who participated in our Report with any kind of contribution. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ The following companies agreed to be publicly named and gave us by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to: Creative precious content to be published: Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. Dreem Neural Sense Emotiv Neuralya Halo Neuroscience Paradromics Mindmaze Pymetrics Neuron Guard Synetiq We would also like to thank the following individuals for helping us with precious suggestions and information: Russel Poldrack, Professor of Psychology at Stanford University, CA, USA; John Dylan-Haynes, Professor at the Bernstein Center for Computational Neuroscience Berlin, Germany; Carlo Miniussi, Director of Center for Mind/Brain Sciences – CIMeC, University of Trento, Rovereto TN Italy; Zaira Cattaneo, Associate Professor in Psychobiology and Physiological Psychology, Department of Psychology, University of Milano-Bicocca, Milano, Italy; Nadia Bolognini, University of Milano Bicocca, Department of Psychology, & IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano, Laboratory of Neuropsychology; Dario Nardi, Author, speaker and expert in the fields of neuroscience and personality; Intesa Sanpaolo Innovation Center Nick Chater, Professor of Behavioral Science at Warwick Business School; assumes no responsibility on the Enrico Maria Cervellati, Associate Professor of Corporate Finance external linked content, both in terms of at the Department of Management Ca’ Foscari University of Venice; availability that of immutability in time. -

Emotional Reasoning and Parent-Based Reasoning in Normal Children

Morren, M., Muris, P., Kindt, M. Emotional reasoning and parent-based reasoning in normal children. Child Psychiatry and Human Development: 35, 2004, nr. 1, p. 3-20 Postprint Version 1.0 Journal website http://www.springerlink.com/content/105587/ Pubmed link http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dop t=Abstract&list_uids=15626322&query_hl=45&itool=pubmed_docsum DOI 10.1023/B:CHUD.0000039317.50547.e3 Address correspondence to M. Morren, Department of Medical, Clinical, and Experimental Psychology, Maastricht University, P.O. Box 616, 6200 MD Maastricht, The Netherlands; e-mail: [email protected]. Emotional Reasoning and Parent-based Reasoning in Normal Children MATTIJN MORREN, MSC; PETER MURIS, PHD; MEREL KINDT, PHD DEPARTMENT OF MEDICAL, CLINICAL AND EXPERIMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY, MAASTRICHT UNIVERSITY, THE NETHERLANDS ABSTRACT: A previous study by Muris, Merckelbach, and Van Spauwen1 demonstrated that children display emotional reasoning irrespective of their anxiety levels. That is, when estimating whether a situation is dangerous, children not only rely on objective danger information but also on their own anxiety-response. The present study further examined emotional reasoning in children aged 7–13 years (N =508). In addition, it was investigated whether children also show parent-based reasoning, which can be defined as the tendency to rely on anxiety-responses that can be observed in parents. Children completed self-report questionnaires of anxiety, depression, and emotional and parent-based reasoning. Evidence was found for both emotional and parent-based reasoning effects. More specifically, children’s danger ratings were not only affected by objective danger information, but also by anxiety-response information in both objective danger and safety stories. -

![Arxiv:2011.03588V1 [Cs.CL] 6 Nov 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9395/arxiv-2011-03588v1-cs-cl-6-nov-2020-1219395.webp)

Arxiv:2011.03588V1 [Cs.CL] 6 Nov 2020

Hostility Detection Dataset in Hindi Mohit Bhardwajy, Md Shad Akhtary, Asif Ekbalz, Amitava Das?, Tanmoy Chakrabortyy yIIIT Delhi, India. zIIT Patna, India. ?Wipro Research, India. fmohit19014,tanmoy,[email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Despite Hindi being the third most spoken language in the world, and a significant presence of Hindi content on social In this paper, we present a novel hostility detection dataset in Hindi language. We collect and manually annotate ∼ 8200 media platforms, to our surprise, we were not able to find online posts. The annotated dataset covers four hostility di- any significant dataset on fake news or hate speech detec- mensions: fake news, hate speech, offensive, and defamation tion in Hindi. A survey of the literature suggest a few works posts, along with a non-hostile label. The hostile posts are related to hostile post detection in Hindi, such as (Kar et al. also considered for multi-label tags due to a significant over- 2020; Jha et al. 2020; Safi Samghabadi et al. 2020); however, lap among the hostile classes. We release this dataset as part there are two basic issues with these works - either the num- of the CONSTRAINT-2021 shared task on hostile post detec- ber of samples in the dataset are not adequate or they cater tion. to a specific dimension of the hostility only. In this paper, we present our manually annotated dataset for hostile posts 1 Introduction detection in Hindi. We collect more than ∼ 8200 online so- The COVID-19 pandemic has changed our lives forever, cial media posts and annotate them as hostile and non-hostile both online and offline. -

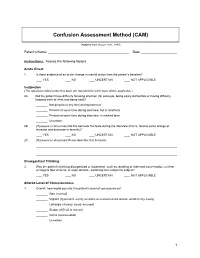

Confusion Assessment Method (CAM)

Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) (Adapted from Inouye et al., 1990) Patient’s Name: Date: Instructions: Assess the following factors. Acute Onset 1. Is there evidence of an acute change in mental status from the patient’s baseline? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE Inattention (The questions listed under this topic are repeated for each topic where applicable.) 2A. Did the patient have difficulty focusing attention (for example, being easily distractible or having difficulty keeping track of what was being said)? Not present at any time during interview Present at some time during interview, but in mild form Present at some time during interview, in marked form Uncertain 2B. (If present or abnormal) Did this behavior fluctuate during the interview (that is, tend to come and go or increase and decrease in severity)? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE 2C. (If present or abnormal) Please describe this behavior. Disorganized Thinking 3. Was the patient’s thinking disorganized or incoherent, such as rambling or irrelevant conversation, unclear or illogical flow of ideas, or unpredictable, switching from subject to subject? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE Altered Level of Consciousness 4. Overall, how would you rate this patient’s level of consciousness? Alert (normal) Vigilant (hyperalert, overly sensitive to environmental stimuli, startled very easily) Lethargic (drowsy, easily aroused) Stupor (difficult to arouse) Coma (unarousable) Uncertain 1 Disorientation 5. Was the patient disoriented at any time during the interview, such as thinking that he or she was somewhere other than the hospital, using the wrong bed, or misjudging the time of day? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE Memory Impairment 6.