Panic Disorder Issue Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conflict, Arousal, and Logical Gut Feelings

CONFLICT, AROUSAL, AND LOGICAL GUT FEELINGS Wim De Neys1, 2, 3 1 ‐ CNRS, Unité 3521 LaPsyDÉ, France 2 ‐ Université Paris Descartes, Sorbonne Paris Cité, Unité 3521 LaPsyDÉ, France 3 ‐ Université de Caen Basse‐Normandie, Unité 3521 LaPsyDÉ, France Mailing address: Wim De Neys LaPsyDÉ (Unité CNRS 3521, Université Paris Descartes) Sorbonne - Labo A. Binet 46, rue Saint Jacques 75005 Paris France [email protected] ABSTRACT Although human reasoning is often biased by intuitive heuristics, recent studies on conflict detection during thinking suggest that adult reasoners detect the biased nature of their judgments. Despite their illogical response, adults seem to demonstrate a remarkable sensitivity to possible conflict between their heuristic judgment and logical or probabilistic norms. In this chapter I review the core findings and try to clarify why it makes sense to conceive this logical sensitivity as an intuitive gut feeling. CONFLICT, AROUSAL, AND LOGICAL GUT FEELINGS Imagine you’re on a game show. The host shows you two metal boxes that are both filled with $100 and $1 dollar bills. You get to draw one note out of one of the boxes. Whatever note you draw is yours to keep. The host tells you that box A contains a total of 10 bills, one of which is a $100 note. He also informs you that Box B contains 1000 bills and 99 of these are $100 notes. So box A has got one $100 bill in it while there are 99 of them hiding in box B. Which one of the boxes should you draw from to maximize your chances of winning $100? When presented with this problem a lot of people seem to have a strong intuitive preference for Box B. -

Panic Disorder

Panic Disorder The Anxiety Disorders Association of America (ADAA) is a national 501 (c)3 nonprofit organization whose My heart’s pounding, mission is to promote the prevention, treatment and cure of anxiety disorders and to improve the lives of all it’s hard to breathe. people who suffer from them. Help ADAA help others. Donate now at www.adaa.org. “I feel like I’m going to go crazy or die. For information visit www.adaa.org or contact I have to get out Anxiety Disorders Association of America 8730 Georgia Ave., Ste. 600 of here NOW. Silver Spring, MD 20910 Phone: 240-485-1001 ” Anxiety Disorders Association of America What is Panic Disorder? About Anxiety Disorders We’ve all experienced that gut-wrenching fear when suddenly faced with a threatening or dangerous situation. Crossing the street as a car shoots out of nowhere, losing a child in Anxiety is a normal part of living. It’s the body’s way of telling the playground or hearing someone scream fire in a crowded us something isn’t right. It keeps us from harm’s way and theater. The momentary panic sends chills down our spines, prepares us to act quickly in the face of danger. However, for causes our hearts to beat wildly, our stomachs to knot and some people, anxiety is persistent, irrational and overwhelming. our minds to fill with terror. When the danger passes, so do It may get in the way of day-to-day activities and even make the symptoms. We’re relieved that the dreaded terror didn’t them impossible. -

The Ontogeny of Chronic Distress: Emotion Dysregulation Across The

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect The ontogeny of chronic distress: emotion dysregulation across the life span and its implications for psychological and physical health 1,2 1 1 Sheila E Crowell , Megan E Puzia and Mona Yaptangco Development is characterized by continuity and change across from a multiple-levels-of-analysis perspective across de- the lifespan. This is especially true of emotions and emotion velopment. This reveals processes by which early, bio- regulation strategies, which become increasingly complex and logically-based trait vulnerabilities interact with complex variegated over development. Recently, researchers have contextual factors, heightening risk for multiple condi- begun to characterize severe emotion dysregulation (ED) tions. From this perspective, many diagnoses that are across the life span. In particular, there is increasing data perceived as distinct can be demonstrated to have com- delineating mechanisms by which emotional distress leads to mon origins and, therefore, to co-occur at higher-than- poor health, early mortality, and intergenerational transmission expected rates at single time-points and over the life span. of psychopathology. In this review, we present converging evidence that many physical and psychological problems have The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders identifiable and treatable origins in childhood ED. When the (DSM-5 [4]) is the predominant tool for cataloging and literature is examined from an ontogenic process perspective it diagnosing mental disorders. Diagnoses are listed as becomes clear that many phenotypically distinct forms of discrete entities, in spite of a wealth of research ques- mental and physical distress emerge from the same underlying tioning the categorical system [5]. -

![Arxiv:2011.03588V1 [Cs.CL] 6 Nov 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9395/arxiv-2011-03588v1-cs-cl-6-nov-2020-1219395.webp)

Arxiv:2011.03588V1 [Cs.CL] 6 Nov 2020

Hostility Detection Dataset in Hindi Mohit Bhardwajy, Md Shad Akhtary, Asif Ekbalz, Amitava Das?, Tanmoy Chakrabortyy yIIIT Delhi, India. zIIT Patna, India. ?Wipro Research, India. fmohit19014,tanmoy,[email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Despite Hindi being the third most spoken language in the world, and a significant presence of Hindi content on social In this paper, we present a novel hostility detection dataset in Hindi language. We collect and manually annotate ∼ 8200 media platforms, to our surprise, we were not able to find online posts. The annotated dataset covers four hostility di- any significant dataset on fake news or hate speech detec- mensions: fake news, hate speech, offensive, and defamation tion in Hindi. A survey of the literature suggest a few works posts, along with a non-hostile label. The hostile posts are related to hostile post detection in Hindi, such as (Kar et al. also considered for multi-label tags due to a significant over- 2020; Jha et al. 2020; Safi Samghabadi et al. 2020); however, lap among the hostile classes. We release this dataset as part there are two basic issues with these works - either the num- of the CONSTRAINT-2021 shared task on hostile post detec- ber of samples in the dataset are not adequate or they cater tion. to a specific dimension of the hostility only. In this paper, we present our manually annotated dataset for hostile posts 1 Introduction detection in Hindi. We collect more than ∼ 8200 online so- The COVID-19 pandemic has changed our lives forever, cial media posts and annotate them as hostile and non-hostile both online and offline. -

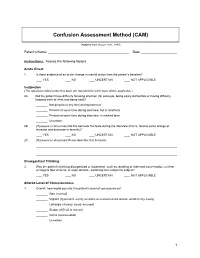

Confusion Assessment Method (CAM)

Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) (Adapted from Inouye et al., 1990) Patient’s Name: Date: Instructions: Assess the following factors. Acute Onset 1. Is there evidence of an acute change in mental status from the patient’s baseline? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE Inattention (The questions listed under this topic are repeated for each topic where applicable.) 2A. Did the patient have difficulty focusing attention (for example, being easily distractible or having difficulty keeping track of what was being said)? Not present at any time during interview Present at some time during interview, but in mild form Present at some time during interview, in marked form Uncertain 2B. (If present or abnormal) Did this behavior fluctuate during the interview (that is, tend to come and go or increase and decrease in severity)? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE 2C. (If present or abnormal) Please describe this behavior. Disorganized Thinking 3. Was the patient’s thinking disorganized or incoherent, such as rambling or irrelevant conversation, unclear or illogical flow of ideas, or unpredictable, switching from subject to subject? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE Altered Level of Consciousness 4. Overall, how would you rate this patient’s level of consciousness? Alert (normal) Vigilant (hyperalert, overly sensitive to environmental stimuli, startled very easily) Lethargic (drowsy, easily aroused) Stupor (difficult to arouse) Coma (unarousable) Uncertain 1 Disorientation 5. Was the patient disoriented at any time during the interview, such as thinking that he or she was somewhere other than the hospital, using the wrong bed, or misjudging the time of day? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE Memory Impairment 6. -

Children's Mental Health Disorder Fact Sheet for the Classroom

1 Children’s Mental Health Disorder Fact Sheet for the Classroom1 Disorder Symptoms or Behaviors About the Disorder Educational Implications Instructional Strategies and Classroom Accommodations Anxiety Frequent Absences All children feel anxious at times. Many feel stress, for example, when Students are easily frustrated and may Allow students to contract a flexible deadline for Refusal to join in social activities separated from parents; others fear the dark. Some though suffer enough have difficulty completing work. They worrisome assignments. Isolating behavior to interfere with their daily activities. Anxious students may lose friends may suffer from perfectionism and take Have the student check with the teacher or have the teacher Many physical complaints and be left out of social activities. Because they are quiet and compliant, much longer to complete work. Or they check with the student to make sure that assignments have Excessive worry about homework/grades the signs are often missed. They commonly experience academic failure may simply refuse to begin out of fear been written down correctly. Many teachers will choose to Frequent bouts of tears and low self-esteem. that they won’t be able to do anything initial an assignment notebook to indicate that information Fear of new situations right. Their fears of being embarrassed, is correct. Drug or alcohol abuse As many as 1 in 10 young people suffer from an AD. About 50% with humiliated, or failing may result in Consider modifying or adapting the curriculum to better AD also have a second AD or other behavioral disorder (e.g. school avoidance. Getting behind in their suit the student’s learning style-this may lessen his/her depression). -

RELATIONAL EMPATHY 1 Running Head

RELATIONAL EMPATHY 1 Running head: RELATIONAL EMPATHY The Interpersonal Functions of Empathy: A Relational Perspective Alexandra Main, Eric A. Walle, Carmen Kho, & Jodi Halpern Alexandra Main Carmen Kho University of California, Merced University of California, Merced 5200 N Lake Road 5200 N Lake Road Merced, CA 95343 Merced, CA 95343 Phone: 209-228-2429 Phone: 714-253-6163 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Eric A. Walle Jodi Halpern University of California, Merced University of California, Berkeley 5200 N Lake Road 570 University Hall Merced, CA 95343 Berkeley, CA 94720 Phone: 209-228-4634 Phone: 510-642-4366 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Alexandra Main, Psychological Sciences, 5200 North Lake Road, University of California, Merced, CA 95343. Phone: 209-228-2429, Email: [email protected] RELATIONAL EMPATHY 2 Abstract Empathy is an extensively studied construct, but operationalization of effective empathy is routinely debated in popular culture, theory, and empirical research. This paper offers a process-focused approach emphasizing the relational functions of empathy in interpersonal contexts. We argue that this perspective offers advantages over more traditional conceptualizations that focus on primarily intrapsychic features (i.e., within the individual). Our aim is to enrich current conceptualizations and empirical approaches to the study of empathy by drawing on psychological, philosophical, medical, linguistic, and anthropological perspectives. In doing so, we highlight the various functions of empathy in social interaction, underscore some underemphasized components in empirical studies of empathy, and make recommendations for future research on this important area in the study of emotion. -

Does Psychomotor Agitation in Major Depressive Episodes Indicate Bipolarity? Evidence from the Zurich Study

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by RERO DOC Digital Library Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci (2009) 259:55–63 DOI 10.1007/s00406-008-0834-7 ORIGINAL PAPER Jules Angst Æ Alex Gamma Æ Franco Benazzi Æ Vladeta Ajdacic Æ Wulf Ro¨ssler Does psychomotor agitation in major depressive episodes indicate bipolarity? Evidence from the Zurich Study Received: 4 September 2007 / Accepted: 5 June 2008 / Published online: 19 September 2008 j Abstract Background Kraepelin’s partial interpre- were equally associated with the indicators of bipolarity tation of agitated depression as a mixed state of and with anxiety. Longitudinally, agitation and retar- ‘‘manic-depressive insanity’’ (including the current dation were significantly associated with each other concept of bipolar disorder) has recently been the focus (OR = 1.8, 95% CI = 1.0–3.2), and this combined of much research. This paper tested whether, how, and group of major depressives showed stronger associa- to what extent both psychomotor symptoms, agitation tions with bipolarity, with both hypomanic/cyclothy- and retardation in depression are related to bipolarity mic and depressive temperamental traits, and with and anxiety. Method The prospective Zurich Study anxiety. Among agitated, non-retarded depressives, assessed psychiatric and somatic syndromes in a unipolar mood disorder was even twice as common as community sample of young adults (N = 591) (aged bipolar mood disorder. Conclusion Combined agitated 20 at first interview) by six interviews over 20 years and retarded major depressive states are more often (1979–1999). Psychomotor symptoms of agitation and bipolar than unipolar, but, in general, agitated retardation were assessed by professional interviewers depression (with or without retardation) is not more from age 22 to 40 (five interviews) on the basis of the frequently bipolar than retarded depression (with or observed and reported behaviour within the interview without agitation), and pure agitated depression is even section on depression. -

Redalyc.Emotions and the Emotional Disorders: a Quantitative

International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology ISSN: 1697-2600 [email protected] Asociación Española de Psicología Conductual España Watson, David; Clark, Lee Anna; Stasik, Sara M. Emotions and the emotional disorders: A quantitative hierarchical perspective International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, vol. 11, núm. 3, 2011, pp. 429-442 Asociación Española de Psicología Conductual Granada, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=33719289001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative © International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology ISSN 1697-2600 print ISSN 2174-0852 online 2011, Vol. 11, Nº 3, pp. 429-442 Emotions and the emotional disorders: A quantitative hierarchical perspective David Watson1, Lee Anna Clark, and Sara M. Stasik (University of Notre Dame, USA) ABSTRACT. Previous evidence has established that general negative affect represents a non-specific factor common to both anxiety and depression, whereas low positive affect is more specifically related to the latter. Little is known, however, about how specific, lower order affects relate to these constructs. We investigated how six emotional disorders—major depression, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), panic disorder, social phobia, and obsessive compulsive disorder — are linked to both general and specific types of affect in two samples (Ns = 331 and 253), using the Expanded Form of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS- X). Replicating previous results, the General Negative Affect scale was nonspecifically related to the emotional disorders, whereas General Positive Affect had a specific (inverse) association with major depression. -

Preliminary Evidence on the Somatic Marker Hypothesis Applied to Investment Choices

Preliminary evidence on the Somatic Marker Hypothesis applied to investment choices Article Accepted Version Cantarella, S., Hillenbrand, C., Aldridge-Waddon, L. and Puzzo, I. (2018) Preliminary evidence on the Somatic Marker Hypothesis applied to investment choices. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics, 11 (4). pp. 228- 238. ISSN 1937-321X doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/npe0000097 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/80454/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/npe0000097 Publisher: American Psychological Association All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online The SMH in Investment Choices Preliminary evidence on the Somatic Marker Hypothesis applied to investment choices Simona Cantarella and Carola Hillenbrand University of Reading Luke Aldridge-Waddon University of Bath Ignazio Puzzo City University of London Words count: 5058 Figures: 5 Tables: 1 Manuscript accepted on the 06/08/2018 1 The SMH in Investment Choices Abstract The somatic marker hypothesis (SMH) is one of the more dominant physiological models of human decision making and yet is seldom applied to decision making in financial investment scenarios. This study provides preliminary evidence about the application of the SMH in investment choices using heart rate (HR) and skin conductance response (SCRs) measures. -

Anxiety Disorders: Diagnosis & Treatment

Anxiety Disorders: Diagnosis & Treatment David Liu MD, MS Health Sciences Assistant Clinical Professor UC Davis Department of Psychiatry and Behavior Sciences Disclosures • I have no financial relationships to disclose relating to the subject matter of this presentation Learning Objectives 1. Review the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Panic Disorder 2. Recognize differential diagnosis of GAD and Panic Disorder 3. Appreciate common co-morbidities to Anxiety disorders 4. Understand approach towards management and treatment options for Anxiety disorders in the primary care setting Primary Care is the ‘De Facto’ Mental Health System What is Anxiety? Begins as ordinary, day-to-day Begins to effect situation. daily life Excessive DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Generalized Anxiety Disorder A. Excessive anxiety and worry (apprehensive expectation), occurring more days than not for at least 6 months, about a number of events or activities (such as work or school performance) B. The individual finds it difficult to control the worry. C. The anxiety and worry are associated with three (or more) of the following six symptoms (With at least some symptoms having been presents for more days than not for the past 6 months). Note: Only one item is required in children – 1. Restlessness or feeling keyed up or on edge. – 2. Being easily fatigued. – 3. Difficulty concentrating or mind going blank. – 4. Irritability. – 5. Muscle tension. – 6. Sleep disturbance (difficulty falling or staying asleep, or restless, unsatisfying sleep) DSM-5 DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Generalized Anxiety Disorder (cont.) D. The anxiety, worry, or physical symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social occupational, or other important areas of functioning. -

Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety Disorders Everyone experiences anxiety. However, when feelings of intense fear and distress are overwhelming and prevent us from doing everyday things, an anxiety disorder may be the cause. Anxiety disorders are the most common mental health concern in the United States. An estimated 40 million adults in the U.S., or 18%, have an anxiety disorder. Approximately 8% of children and teenagers experience the negative impact of an anxiety disorder at school and at home. Symptoms Just like with any mental illness, people with anxiety disorders experience symptoms differently. But for most people, anxiety changes how they function day-to-day. People can experience one or more of the following symptoms: Emotional symptoms: • Feelings of apprehension or dread • Feeling tense and jumpy • Restlessness or irritability • Anticipating the worst and being watchful for signs of danger Physical symptoms: • Pounding or racing heart and shortness of breath • Upset stomach • Sweating, tremors and twitches • Headaches, fatigue and insomnia • Upset stomach, frequent urination or diarrhea Types of Anxiety Disorders Different anxiety disorders have various symptoms. This also means that each type of anxiety disorder has its own treatment plan. The most common anxiety disorders include: • Panic Disorder. Characterized by panic attacks—sudden feelings of terror— sometimes striking repeatedly and without warning. Often mistaken for a heart attack, a panic attack causes powerful, physical symptoms including chest pain, heart palpitations, dizziness, shortness of breath and stomach upset. • Phobias. Most people with specific phobias have several triggers. To avoid panicking, someone with specific phobias will work hard to avoid their triggers. Depending on the type and number of triggers, this fear and the attempt to control it can seem to take over a person’s life.