M23(Mouvement Du 23 Mars)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congo Leaving the Shadows an Analysis of Shadow Networks Relating to Peace Building in the Congo

Congo Leaving the Shadows An analysis of shadow networks relating to peace building in the Congo Congo Leaving the Shadows An analysis of shadow networks relating to peace building in the Congo Josje van Workum 900110972020 Wageningen University Bachelor Thesis International Developmentstudies Supervisor: Elisabet Rasch 14th December, 2012 Summary This paper reviews the potential contributory role of shadow networks integrated in peace building attempts. This will be analysed through a relational approach between State practices and the characteristics of a shadow network. Firstly, shadow networks will be reviewed conceptually, how they become established and how they operate around the illicit trade of minerals. Secondly, a threefold analysis of the relation between shadow networks, the State and peace building will be presented. In order to illustrate this relation, the next section will offer a case study of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The resource richness and (post)conflict context of the Eastern Kivu provinces in Congo offer a suitable environment for shadow networks to rise. The different armed groups that are involved in these networks will be analysed with a particular focus on Congo’s national military, the FARDC. By studying the engagement of the FARDC in shadow networks this paper will eventually offer a perspective for future peace building projects to include shadow networks into their operations. - 1 - Congo Leaving the Shadows Josje van Workum Table of content Summary ................................................................................................................................ -

Pdf | 277.85 Kb

Regional Overview – Africa 2 October 2018 acleddata.com/2018/10/02/regional-overview-africa-2-october-2018/ Margaux Pinaud October 2, 2018 There were several key developments in Africa during the week of September 23rd. In Burkina Faso, reports of heavy attacks on civilians by the security forces last week add another layer to the deepening instability in the country. On September 24th, no fewer than 29 individuals were summarily executed by the defense and security forces in two incidents in Petegoli and Inata villages of Soum province (Sahel region). The forces claimed they were militants. On the same day, in Kompienga province (Est region), government forces killed a young person while raiding an Imam’s house in Kabonga village. In a closely linked incident on September 24th, unknown gunmen abducted and later executed the deputy Imam of Kompienga from a village close to Kabonga. A few days after the violence, opposition leaders and civil society activists held a large rally in the capital, Ouagadougou, denouncing President Kabore’s inability to provide security to the Burkinabes and demanding the sacking of Clement Pengwende Sawadogo and Jean-Claude Bouda, respectively Ministers of Security and Defense. In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), the Resistance to the Rule of Law in Burundi (RED-TABARA) and the Front for Democracy in Burundi (FRODEBU) remain major security threats, despite being considered ‘foreign’ groups. The ADF have been particularly active in 2018 in Nord-Kivu, ambushing FARDC and MONUSCO forces on a regular basis primarily in the Oicha and Beni territories, as well as attacking civilians in villages in these areas. -

Ocha Drc Population Movements in Eastern Dr Congo October – December 2009

Population Movements in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo OCHA DRC POPULATION MOVEMENTS IN EASTERN DR CONGO OCTOBER – DECEMBER 2009 January 2010 1 Population Movements in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo 1. OVERVIEW The humanitarian situation and movement of populations in 2009 have been heavily influenced by military operations and the still prevailing insecurity in a number of areas in the eastern provinces. Between January 20 and February 25 2009, the Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo (FARDC) and the Rwanda Defence Forces (RDF) conducted joint operations (Umoja Wetu) in North Kivu against the Forces Démocratiques pour le Liberation du Rwanda (FDLR). In March 2009 a second military operation (Kimia II) was launched in North Kivu and South Kivu. Lubero, Rutshuru, Masisi and Walikale are the territories in North Kivu where major displacements have been reported since March 2009. In South Kivu the most affected areas are Kalehe, Uvira and Shabunda. The attacks carried out by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), a Ugandan militia, in the Orientale province since September 2008 have spread from the Haut Uele district to the Bas Uele in 2009. The population is victim of atrocities and acts of extreme violence: killings, rapes, kidnapping and looting leading to population displacements in many locations of the districts. N. IDPs per Province 800 000 767 399 730 941 700 000 600 000 Haut Uele 500 000 Bas Uele Ituri North Kivu 400 000 South Kivu Equateur 239 210 Katanga 300 000 165 472 200 000 58 937 60 000 100 000 14 000 0 Note: Ituri, Haut Uele and Bas Uele are districts of the Orientale province During the reporting period (October ‐ December 2009) some displacements have been reported in the Katanga province where about 14.000 people have moved from South Kivu due to the military operations in the area bordering Katanga. -

Democratic Republic of the Congo INDIVIDUALS

CONSOLIDATED LIST OF FINANCIAL SANCTIONS TARGETS IN THE UK Last Updated:18/02/2021 Status: Asset Freeze Targets REGIME: Democratic Republic of the Congo INDIVIDUALS 1. Name 6: BADEGE 1: ERIC 2: n/a 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: --/--/1971. Nationality: Democratic Republic of the Congo Address: Rwanda (as of early 2016).Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):DRC0028 (UN Ref): CDi.001 (Further Identifiying Information):He fled to Rwanda in March 2013 and is still living there as of early 2016. INTERPOL-UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/notice/search/un/5272441 (Gender):Male Listed on: 23/01/2013 Last Updated: 20/01/2021 Group ID: 12838. 2. Name 6: BALUKU 1: SEKA 2: n/a 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: --/--/1977. a.k.a: (1) KAJAJU, Mzee (2) LUMONDE (3) LUMU (4) MUSA Nationality: Uganda Address: Kajuju camp of Medina II, Beni territory, North Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo (last known location).Position: Overall leader of the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) (CDe.001) Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):DRC0059 (UN Ref):CDi.036 (Further Identifiying Information):Longtime member of the ADF (CDe.001), Baluku used to be the second in command to ADF founder Jamil Mukulu (CDi.015) until he took over after FARDC military operation Sukola I in 2014. Listed on: 07/02/2020 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 Group ID: 13813. 3. Name 6: BOSHAB 1: EVARISTE 2: n/a 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. -

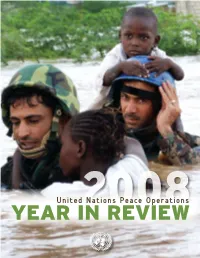

Year in Review 2008

United Nations Peace Operations YEAR IN2008 REVIEW asdf TABLE OF CONTENTS 12 ] UNMIS helps keep North-South Sudan peace on track 13 ] MINURCAT trains police in Chad, prepares to expand 15 ] After gaining ground in Liberia, UN blue helmets start to downsize 16 ] Progress in Côte d’Ivoire 18 ] UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea is withdrawn 19 ] UNMIN assists Nepal in transition to peace and democracy 20 ] Amid increasing insecurity, humanitarian and political work continues in Somalia 21 ] After nearly a decade in Kosovo, UNMIK reconfigures 23 ] Afghanistan – Room for hope despite challenges 27 ] New SRSG pursues robust UN mandate in electoral assistance, reconstruction and political dialogue in Iraq 29 ] UNIFIL provides a window of opportunity for peace in southern Lebanon 30 ] A watershed year for Timor-Leste 33 ] UN continues political and peacekeeping efforts in the Middle East 35 ] Renewed hope for a solution in Cyprus 37 ] UNOMIG carries out mandate in complex environment 38 ] DFS: Supporting peace operations Children of Tongo, Massi, North Kivu, DRC. 28 March 2008. UN Photo by Marie Frechon. Children of Tongo, 40 ] Demand grows for UN Police 41 ] National staff make huge contributions to UN peace 1 ] 2008: United Nations peacekeeping operations observes 60 years of operations 44 ] Ahtisaari brings pride to UN peace efforts with 2008 Nobel Prize 6 ] As peace in Congo remains elusive, 45 ] Security Council addresses sexual violence as Security Council strengthens threat to international peace and security MONUC’s hand [ Peace operations facts and figures ] 9 ] Challenges confront new peace- 47 ] Peacekeeping contributors keeping mission in Darfur 48 ] United Nations peacekeeping operations 25 ] Peacekeepers lead response to 50 ] United Nations political and peacebuilding missions disasters in Haiti 52 ] Top 10 troop contributors Cover photo: Jordanian peacekeepers rescue children 52 ] Surge in uniformed UN peacekeeping personnel from a flooded orphanage north of Port-au-Prince from1991-2008 after the passing of Hurricane Ike. -

Rwanda's Support to the March 23 Movement (M23)

Opinion Beyond the Single Story: Rwanda’s Support to the March 23 Movement (M23) Alphonse Muleefu* Introduction Since the news broke about the mutiny of some of the Congolese Armed Forces - Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo (FARDC) in April 2012 and their subsequent creation of the March 23 Movement (M23), we have been consistently supplied with one story about the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). A story that puts much emphasis on allegations that the government of Rwanda and later to some lesser extent that of Uganda are supporting M23 against the government of the DRC. This narrative was reinforced when the UN Group of Experts for the DRC (GoE) issued an Addendum of 48 pages on June 25, 20121 making allegations similar to those already made in Human Rights Watch’s (HRW) report of June 3, 20122, that the government of Rwanda was providing direct support in terms of recruitment, encouraging desertion of FARDC soldiers, providing weapons, ammunitions, intelligence, political advice to the M23, violating measures concerning the freezing of assets and collaborating with certain individuals. In response, the government of Rwanda issued a 131-page rebuttal on July 27, 2012, in which it denied all allegations and challenged the evidence given in support of each claim.3 On November 15, 2012, the GoE submitted its previously leaked report in which, in addition to the allegations made earlier, it claimed that the effective commander of M23 is Gen. James Kabarebe, Rwanda’s Minister of Defence, and that the senior officials of the government of Uganda had provided troop reinforcements, supplied weapons, offered technical assistance, joint planning, political advice and external relations.4 The alleged support provided by Ugandan officials was described as “subtle but crucial”, and the evidence against Rwanda was described as “overwhelming and compelling”. -

Democratic Republic of the Congo

1 Democratic Republic of the Congo Authors: ACODESKI, AFASKIAPFVASK CAFCO, CENADEP, FED, IFDH-NGABO IGNIYUS- RDC, OSODI, SOPADE, SIPOFA WILPF/RDC Researchers: Annie Matundu Mbambi (WILPF/RDC), Jeannine Mukanirwa (CENADEP), Rose Mutombo Kiese (CAFCO) Acknowledgments: We thank all people whose work made this report possible. In particular, we would like to thank the organizations from South Kivu: ACODESKI, AFASKI, ASK, APFV FED, IFDH-NGABO IGNITUS-DRC, OSODI, SOPADE, SIPROFA, CEPFE, as well as the focal provincial points of the CAFCO organization, who collaborated to contribute to this report. This report wouldn’t be possible without the constant support from GNWP-ICAN. Their help to the Congolese women shed light on many aspects of the qualitative research and the action research on the implementation of the UN Security Council Resolution 1325i in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Finally, we would also like to thank all the resource persons, and the participants of the consultative workshops for their suggestions and changes to the report. 2 Women Count 2014 Global Civil Society Monitoring Report List of Acronyms ACODESKI Community Association for the Development of South Kivu (Association Communautaire pour le développement du Sud-Kivu) AFASKI Association of Women Lawyers from South Kivu (Association de Femmes Avocates du Sud-Kivu) AFDL Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire (Alliance des Forces Démocratiques pour la Libération du Congo) APFV Association of Vulnerable Rural Women (Association paysanne des -

Executive Summary

Monthly Protection Monitoring Report – North Kivu September 2015 Executive Summary 2845 incidents have been recorded in September 2015. The number has decreased by 6,3% compared to August 2015 pendant, when 3037 incidents were reported. The territory Incidents per territory of Rutshuru has had the BENI 369 highest LUBERO 369 number of MASISI 639 incidents in NYIRAGONGO 133 September RUTSHURU 919 2015 WALIKALE 416 TOTAL 2845 Incidents per Incidents per alleged perpetrator category of victim Nombre des cas par type d’incident The majority of incidents in September 2015 were violations to the right of property and liberty PROTECTION MONITORING PMS Province du Nord Kivu 2 | UNHCR Protection Monitoring Nor th K i v u – Sept. Monthly Report PROTECTION MONITORING PMS Province du Nord Kivu I. Summary of main protection concerns Throughout September 2015, the PMS has registered 59,8% less internal displacement than in August 2015. This decrease can be justified by the relative calm perceived in significant displacement areas. On 17 September 2015, alleged NDC Cheka members pillaged Kalehe village to the Northeast of Bunyatenge and kidnapped around 30 people that were forced to transport the stolen goods to Mwanza and Mutiri, in Lubero territory. II. Protection context by territory MASISI The security situation in Masisi was characterised by clashes between FARDC and FDLR, between two different factions of FDDH (FDDH/Tuombe and FDDH/Mugwete) and between FARDC and APCLS. These conflicts have led to the massive displacement of the population from the areas affected by fighting followed by looting, killings and other violations. In Bibwe, around 400 families were displaced, among which 72 households are staying in a church and a school in Bibwe and around 330 families created a new site, accessible by car, around 2km from the Bibwe site. -

Issue Brief Renewing MONUSCO's Mandate

Issue Brief Renewing MONUSCO’s Mandate: What Role Beyond the Elections? MAY 2011 This issue brief was prepared by Executive Summary Arthur Boutellis of IPI and Guillaume As they prepare to discuss the renewal of MONUSCO’s mandate six months Lacaille, an independent analyst. ahead of general elections in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), The views expressed in this paper the members of the UN Security Council are facing a dilemma. Should they represent those of the authors and limit the role of MONUSCO to the continued protection of civilians in eastern not necessarily those of IPI. IPI Congo, as agreed with President Joseph Kabila, or should they expand its mandate in an attempt to enforce democratic principles before the elections at welcomes consideration of a wide the risk of confronting the incumbent regime? This issue brief argues that range of perspectives in the pursuit MONUSCO should be limited to a technical role in the election—as requested of a well-informed debate on critical by the Congolese authorities—but only on the condition that the international policies and issues in international community reengages President Kabila in a frank political dialogue on long- term democratic governance reforms. affairs. The current security situation does not allow for MONUSCO’s reconfigura - IPI owes a debt of gratitude to its tion or drawdown as of yet. As challenging as it is for the UN mission to many generous donors, whose improve significantly the protection of civilians (PoC) in eastern DRC, the support makes publications like this Congolese security forces are not yet ready to take over MONUSCO’s security one possible. -

620290Wp0democ0box036147

Public Disclosure Authorized WORLD DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2011 BACKGROUND CASE STUDY EMOCRATIC EPUBLIC OF THE ONGO Public Disclosure Authorized D R C Tony Gambino March 2, 2011 (Final Revisions Received) The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the author. They do not necessarily represent the views of the World Development Report 2011 team, the World Public Disclosure Authorized Bank and its affiliated organizations, or those of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent Tony Gambino has worked on development and foreign policy issues for more than thirty years. For the last fourteen years, he has concentrated on the problems of fragile states, with a special focus on the states of Central Africa. He coordinated USAID’s re-engagement in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in 1997 and served there as USAID Mission Director from 2001-2004. He began his work in the Congo in 1979. The author wishes to thank Gérard Prunier, René Lemarchand, Ivor Fung (Director of the UN Regional Centre for Peace and Disarmament in Africa), Rachel Locke, (Head, Africa Team, Office for Conflict Mitigation and Management, Bureau for Africa, USAID), and Thierry Vircoulon (Project Director, Central Africa, International Crisis Group) for their thoughtful, insightful comments. The paper was greatly improved as a result of their questions, concerns, and comments. Remaining flaws are due to the author’s own analytical shortcomings. This paper was largely Public Disclosure Authorized completed in early 2010. Therefore, it does not include information on or analysis of the change from MONUC to MONUSCO or other important events that occurred later in 2010 or in early 2011. -

DR-CONGO December 2013

COUNTRY REPORT: DR-CONGO December 2013 Introduction: other provinces are also grappling with consistently high levels of violence. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DR-Congo) is the sec- ond most violent country in the ACLED dataset when Likewise, in terms of conflict actors, recent international measured by the number of conflict events; and the third commentary has focussed very heavily on the M23 rebel most fatal over the course of the dataset’s coverage (1997 group and their interactions with Congolese military - September 2013). forces and UN peacekeepers. However, while ACLED data illustrates that M23 has constituted the most violent non- Since 2011, violence levels have increased significantly in state actor in the country since its emergence in April this beleaguered country, primarily due to a sharp rise in 2012, other groups including Mayi Mayi militias, FDLR conflict in the Kivu regions (see Figure 1). Conflict levels rebels and unidentified armed groups also represent sig- during 2013 to date have reduced, following an unprece- nificant threats to security and stability. dented peak of activity in late 2012 but this year’s event levels remain significantly above average for the DR- In order to explore key dynamics of violence across time Congo. and space in the DR-Congo, this report examines in turn M23 in North and South Kivu, the Lord’s Resistance Army Across the coverage period, this violence has displayed a (LRA) in northern DR-Congo and the evolving dynamics of very distinct spatial pattern; over half of all conflict events Mayi Mayi violence across the country. The report then occurred in the eastern Kivu provinces, while a further examines MONUSCO’s efforts to maintain a fragile peace quarter took place in Orientale and less than 10% in Ka- in the country, and highlights the dynamics of the on- tanga (see Figure 2). -

Dismissed! Victims of 2015-2018 Brutal Crackdowns in the Democratic Republic of Congo Denied Justice

DISMISSED! VICTIMS OF 2015-2018 BRUTAL CRACKDOWNS IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DENIED JUSTICE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: “Dismissed!”. A drawing by Congolese artist © Justin Kasereka (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AFR 62/2185/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 2. METHODOLOGY 9 3. BACKGROUND: POLITICAL CRISIS 10 3.1 ATTEMPTS TO AMEND THE CONSTITUTION 10 3.2 THE « GLISSEMENT »: THE LONG-DRAWN-OUT ELECTORAL PROCESS 11 3.3 ELECTIONS AT LAST 14 3.3.1 TIMELINE 15 4. VOICES OF DISSENT MUZZLED 19 4.1 ARBITRARY ARRESTS, DETENTIONS AND SYSTEMATIC BANS ON ASSEMBLIES 19 4.1.1 HARASSMENT AND ARBITRARY ARRESTS OF PRO-DEMOCRACY ACTIVISTS AND OPPONENTS 20 4.1.2 SYSTEMATIC AND UNLAWFUL BANS ON ASSEMBLY 21 4.2 RESTRICTIONS OF THE RIGHT TO SEEK AND RECEIVE INFORMATION 23 5.