Defining and Transgressing Norms of Black Female Sexuality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

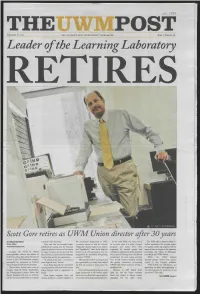

Leader of the Learning Laboratory RETIRES

THE POSTest-, lyob September 6, 2011 THE STUDENT-RUN INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER Issue 2, Volume $6 Leader of the Learning Laboratory RETIRES Scott Gore retires as UWM Union director after 30years By Steve Garrison assistant to the chancellor. the reservations department in 1972, In the early 1970s, the union was a The UAB, still in existence today, is a News Editor Gore said that the biennial budget a position referred to him by a friend. far cry from what it is today. Campus student organization that provides support [email protected] published last spring and the financial Originally a theater major, Gore said he programs and events were often for speakers, events and programs with the impact it may have was part of the reason had "highfalutin" ideas about what he organized by external groups and intent to have an impact on the university, Campus life would be almost he chose to leave, but he also felt that wanted to do after graduation, but was individuals independent of the university community and culture of Milwaukee, unrecognizable without the efforts of after 30 years, it maybe time for a change, intrigued by the possibility of beginning who received funding from the federal according to the UWM website. Scott Gore, who, after almost 30 years of both for him and for the organization. a career at UWM. government. As such, union activities While the UAB allowed service to the UW-Milwaukee campus, "It is kind of my time ... to retool in "My experiences here on campus and were mostly business-minded, serving students greater control over campus announced his retirement as Student some shape or form," he said. -

Tha Carter V Free Download Tha Carter V Free Download

tha carter v free download Tha carter v free download. DOWNLOAD ALBUM: Lil Wayne. Weezy not long ago shared the news of him being the sole owner of Young Money after reaching an agreement with Birdman and Cash Money who was partial owner of the label he founded, and we hope the deal lasts. Rap Artist Lil Wayne has actually finally exposed the release date for his long-awaited album The Cater V. The project has for many years witnessed so much undesirable delays coming from legal disputes between Lil Wayne and his former label boss, Birdman of Cash Money Records. Album: Lil Wayne — Tha Carter V 2018 Free Album Zip Download: The new album, Tha Carter V from American singer and song writer Lil Wayne is his newest and twelfth studio album the the one time best rapper. Album: Lil Wayne — Tha Carter V 2018 Free Album Zip Download: The new album, Tha Carter V from American singer and song writer Lil Wayne is his newest and twelfth studio album the the one time best rapper. There is no description regarding how this reduction in payment associates to Wayne's original claim that Cash Money chose not to release his album. Then, Cash Money became the issue as Birdman was consistently stopping the release of the much-anticipated album. Download Tha Carter V (2018) album zip, rar, by Lil Wayne Mp3 Download. Birdman had to sense disloyalty in the air and Tha Carter V is a small casualty of this blatant disrespect. Now with Lil Wayne jumping on twitter yet again to declare his intentions to quit the game, Birdman again gets the blame. -

Exposing Corruption in Progressive Rock: a Semiotic Analysis of Gentle Giant’S the Power and the Glory

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 EXPOSING CORRUPTION IN PROGRESSIVE ROCK: A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF GENTLE GIANT’S THE POWER AND THE GLORY Robert Jacob Sivy University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2019.459 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Sivy, Robert Jacob, "EXPOSING CORRUPTION IN PROGRESSIVE ROCK: A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF GENTLE GIANT’S THE POWER AND THE GLORY" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 149. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/149 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Spire Light Spire Light

Spire Light Spire Light Spire Light A Journal of Creative Expression Andrew College 2021 2021 2 0 2 1 Spire Light: A Journal of Creative Expression Spire Light: A Journal of Creative Expression Andrew College 2021 Copyright © 2021 by Andrew College All rights reserved. This book or any portion may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review or scholarly journal. ISBN: 978-1-6780-6324-5 Andrew College 501 College Street Cuthbert, GA 39840 www.andrewcollege.edu/spire-light Cover Art: "Small Things," Chris Johnson Cover Design by Heather Bradley Editorial Staff Editor-in-Chief Penny Dearmin Art Editor Noah Varsalona Fiction Editors Kenyaly Quevedo Jermaine Glover Poetry Editor Hasani “Vibez” Comer Creative Nonfiction Editor Penny Dearmin Assistant Layout Editor Cameron Cabarrus www.andrewcollege.edu/spire-light Editor's Notes Penny Dearmin Editor-in-Chief To produce or curate art in this time is an act of service—to ourselves and the world who all need to believe again. We decided to say yes when there is a no at every corner. Yes, we will have our very first contest for the Illumination Prose Prize. Yes, we will accept an ekphrasis prose poem collaboration. Rather than place limits with a themed call for submissions, we did our best to remain open. These pieces should carry you to the hypothetical, a place where there are possibilities to unsee what you think you know. Isn’t that what we have done this year? Escaped? You can be grounded, too. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with James Poyser

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with James Poyser Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Poyser, James, 1967- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with James Poyser, Dates: May 6, 2014 Bulk Dates: 2014 Physical 7 uncompressed MOV digital video files (3:06:29). Description: Abstract: Songwriter, producer, and musician James Poyser (1967 - ) was co-founder of the Axis Music Group and founding member of the musical collective Soulquarians. He was a Grammy award- winning songwriter, musician and multi-platinum producer. Poyser was also a regular member of The Roots, and joined them as the houseband for NBC's The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon. Poyser was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on May 6, 2014, in New York, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2014_143 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Songwriter, producer and musician James Jason Poyser was born in Sheffield, England in 1967 to Jamaican parents Reverend Felix and Lilith Poyser. Poyser’s family moved to West Philadelphia, Pennsylvania when he was nine years old and he discovered his musical talents in the church. Poyser attended Philadelphia Public Schools and graduated from Temple University with his B.S. degree in finance. Upon graduation, Poyser apprenticed with the songwriting/producing duo Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff. Poyser then established the Axis Music Group with his partners, Vikter Duplaix and Chauncey Childs. He became a founding member of the musical collective Soulquarians and went on to write and produce songs for various legendary and award-winning artists including Erykah Badu, Mariah Carey, John Legend, Lauryn Hill, Common, Anthony Hamilton, D'Angelo, The Roots, and Keyshia Cole. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Pdf 1-8., Accessed March 2014

THE BIOCULTURAL IMPACT OF ETHNIC HEALTH AND BEAUTY PRODUCT CONSUMPTION AMONG SOUTH FLORIDA JAMAICAN WOMEN By BRITTANY MONIQUE OSBOURNE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2015 © 2015 Brittany Monique Osbourne To my ancestors and parents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The following dissertation evolved over the course of five years with the help of many people. I would first like to pay honor and respect to my spiritual compass, my creator, whose love and wisdom guided me along this doctoral path. To my ancestors, both ancient and recently transitioned, I pay homage. No amount of verbal libations can ever truly honor the sacrifices they endured, so the living would not have to know their struggles. In particular, I would like to honor those ancestors who survived the Maafa. Without them, I would not be. I would also like to honor my Jamaican ancestors, particularly my Windward Maroon ancestors of Portland Parish. The legacy of their warrior spirits kept me strong throughout this process, and motivated me to continue the good fight of completing this work. I thank my intellectual ancestress Zora Neale Hurston, who I am very proud to have been directly trained by those who were trained by those who trained her. Her ethnographic and literary works spoke to me, and were always a constant reminder that those of us who are a blend of the fine arts and the social sciences are uniquely positioned to be a transformative voice for the voiceless. -

Zine Culture: Identity & Agency Trajectories in an ELA Classroom William K

Kennesaw State University DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University Doctor of Education in Secondary Education Department of Secondary and Middle Grades Dissertations Education Spring 3-13-2017 Zine Culture: Identity & Agency Trajectories in an ELA Classroom William K. Jones Kennesaw State University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/seceddoc_etd Part of the Secondary Education Commons Recommended Citation Jones, William K., "Zine Culture: Identity & Agency Trajectories in an ELA Classroom" (2017). Doctor of Education in Secondary Education Dissertations. 7. http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/seceddoc_etd/7 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Secondary and Middle Grades Education at DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Education in Secondary Education Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Zine Culture: Identity & Agency Trajectories in an ELA Classroom By W. Kyle Jones A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education In Secondary Education English Copyright © W. Kyle Jones 2017 All rights reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My love of writing grew from the moment Ms. B, my readiness teacher, helped me publish my own story of a white cat that visited a magical land after falling into a rainbow. My love of reading began at the age of ten when my dad handed me the book Ender’s Game, and I became immersed in the psychology of a child my age playing the war games of adults. I fortified my love of writing when my friends humored me and read my angsty, teenage poetry and told me they liked it—they were being kind to say the least. -

"Authenticity" in Rap Music by Consumers."

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2010 "Rapping About Authenticity": Exploring the Differences in Perceptions of "Authenticity" in Rap Music by Consumers." James L. Wright UTK, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Social Psychology and Interaction Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Wright, James L., ""Rapping About Authenticity": Exploring the Differences in Perceptions of "Authenticity" in Rap Music by Consumers.". " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2010. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/760 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by James L. Wright entitled ""Rapping About Authenticity": Exploring the Differences in Perceptions of "Authenticity" in Rap Music by Consumers."." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Sociology. Suzaanne B. Kurth, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Robert Emmet Jones; Hoan Bui; Debora Baldwin Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by James L. -

The United Eras of Hip-Hop (1984-2008)

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfgh jklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvb nmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwer The United Eras of Hip-Hop tyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopas Examining the perception of hip-hop over the last quarter century dfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzx 5/1/2009 cvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqLawrence Murray wertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuio pasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghj klzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmrty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqw The United Eras of Hip-Hop ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are so many people I need to acknowledge. Dr. Kelton Edmonds was my advisor for this project and I appreciate him helping me to study hip- hop. Dr. Susan Jasko was my advisor at California University of Pennsylvania since 2005 and encouraged me to stay in the Honors Program. Dr. Drew McGukin had the initiative to bring me to the Honors Program in the first place. I wanted to acknowledge everybody in the Honors Department (Dr. Ed Chute, Dr. Erin Mountz, Mrs. Kim Orslene, and Dr. Don Lawson). Doing a Red Hot Chili Peppers project in 2008 for Mr. Max Gonano was also very important. I would be remiss if I left out the encouragement of my family and my friends, who kept assuring me things would work out when I was never certain. Hip-Hop: 2009 Page 1 The United Eras of Hip-Hop TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS -

The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 A Historical Analysis: The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L. Johnson II Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS: THE EVOLUTION OF COMMERCIAL RAP MUSIC By MAURICE L. JOHNSON II A Thesis submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Maurice L. Johnson II, defended on April 7, 2011. _____________________________ Jonathan Adams Thesis Committee Chair _____________________________ Gary Heald Committee Member _____________________________ Stephen McDowell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicated this to the collective loving memory of Marlena Curry-Gatewood, Dr. Milton Howard Johnson and Rashad Kendrick Williams. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the individuals, both in the physical and the spiritual realms, whom have assisted and encouraged me in the completion of my thesis. During the process, I faced numerous challenges from the narrowing of content and focus on the subject at hand, to seemingly unjust legal and administrative circumstances. Dr. Jonathan Adams, whose gracious support, interest, and tutelage, and knowledge in the fields of both music and communications studies, are greatly appreciated. Dr. Gary Heald encouraged me to complete my thesis as the foundation for future doctoral studies, and dissertation research.