Istanbul Technical University Institute of Science And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Answers and Their Uptake in Standardised Survey Interviews

From Text to Talk Answers and their uptake in standardised survey interviews Published by LOT phone: +31 30 253 6006 Janskerkhof 13 fax: +31 30 253 6000 3512 BL Utrecht e-mail: [email protected] The Netherlands http://wwwlot.let.uu.nl/ Cover illustration: New Connections by S. Unger ISBN-10: 90-78328-08-8 ISBN-13: 978-90-78328-08-7 NUR 632 Copyright © 2006: Sanne van ‘t Hof. All rights reserved. From Text to Talk Answers and their uptake in standardised survey interviews Van Tekst naar Gesprek Antwoorden en hun ontvangst in gestandaardiseerde survey interviews (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de Rector Magnificus, Prof. Dr. W.H. Gispen, ingevolge het besluit van het College voor Promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op vrijdag 6 oktober 2006 des ochtends te 10.30 uur door SANNE VAN ‘T HOF geboren op 24 juli 1976 te Middelburg Promotores: Prof. Dr. Mr. P.J. van de Hoven Faculteit der Letteren Universiteit Utrecht Prof. Dr. W.P. Drew Sociology Department University of York Co-promotor: Dr. A.J. Koole Faculteit der Letteren Universiteit Utrecht Table of contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................... 9 1.1 Opening statement ........................................................9 1.2 Survey research...........................................................10 1.3 The theory of survey research......................................17 -

Smoking and Quitting Behaviour in Lockdown South Africa

SMOKING AND QUITTING BEHAVIOUR IN LOCKDOWN SOUTH AFRICA: RESULTS FROM A SECOND SURVEY Professor Corné van Walbeek Samantha Filby Kirsten van der Zee 21 July 2020 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report is based on the results of an online survey, conducted between 4 June and 19 June 2020. The study was conducted by the Research Unit on the Economics of Excisable Products (REEP), an independent research unit based at the University of Cape Town. It was funded by the African Capacity Building Foundation, which in turn is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. This report follows on from our first report entitled “Lighting up the illicit cigarette market: Smokers’ responses to the cigarette sales ban in South Africa”, which was published on 15 May 2020. That report was based on an online survey conducted between 29 April and 11 May 2020. When the second survey was conducted, the ban on the sales of cigarettes had been extended, even as the country had moved from lockdown Level 4 to Level 3. The questionnaire was distributed on Twitter, Change.org (a petition site) and Moya (a data-free platform). The survey yielded 23 631 usable responses. In contrast to the first study, we did not weigh the data, because the sampling methodology (i.e. online survey) made it impossible to reach the poorer segments of society. We thus do not claim that the data is nationally representative; we report on the characteristics of the sample, not the South African smoking population. In the report we often report the findings by race and gender, because smoking behaviour in South Africa has very pronounced race-gender differences. -

Guidance Document for Administrating the Alaska Native Adult Tobacco Survey

GUIDANCE DOCUMENT Administrating the Alaska Native Adult Tobacco Survey Guidance Document for Administrating the Alaska Native Adult Tobacco Survey Art for front cover: Sierra Gerlach, Health Education and Promotion Council, Inc., 2433 W. Chicago, Suite C, Rapid City, SD 57702 Authors: Victoria A. Albright, MA1 Adriane Niare, MPH, CHES2 Sara Mirza, MPH2 Stacy L. Thorne, PhD, MPH, CHES2 Ralph S. Caraballo, PhD, MPH2 1 RTI International 2 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center of Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, Epidemiology Branch Acknowledgments: Alaska Native Health Board, Anchorage, AK Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, Anchorage, AK Alaska Native Adult Tobacco Survey Coordinator: St. Paul and Unalaska, AK Alaska Native Adult Tobacco Survey Interviewers: St. Paul and Unalaska, AK Alaska Native Adult Tobacco Survey Participants: St. Paul and Unalaska, AK Arctic Slope Native Corporation, Barrow, AK Maniilaq Health Center, Kotzebue, AK Norton Sound Health Corporation, Nome, AK Rita Anniskett Daria Dirks Alyssa Easton, PhD, MPH Jenny Jennings Foerst, PhD Andrea Fenaughty, PhD Nick Gonzales Charlotte Gisvold Corrine Husten, MD, MPH Doreen O. Lacy Brick Lancaster, MA, CHES Barbara Parks, RDH, MPH Jay Macedo, MA Brenna Muldavin, MS Trena Rairdon Loreano Reano, MPA Laura Revels Caroline C Renner Cynthia Tainpeah, RN Ray Tainpeah, MEd, LADC Janis Weber, PhD Suggested citation: Albright VA, Mirza S, Caraballo R, Niare A, Thorne SL. Guidance document for administrating the Alaska Native Adult Tobacco Survey. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010. _________________________________ RTI International is a trade name of Research Triangle Institute. -

Quality Assurance: Guidelines and Documentation

GTSS Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) GLOBAL TOBACCO SURVEILLANCE SYSTEM (GTSS) Quality Assurance: Guidelines and Documentation Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) Quality Assurance: Guidelines and Documentation Version 2.0 November 2010 Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) Comprehensive Standard Protocol ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… GATS Questionnaire Core Questionnaire with Optional Questions Question by Question Specifications GATS Sample Design Sample Design Manual Sample Weights Manual GATS Fieldwork Implementation Field Interviewer Manual Field Supervisor Manual Mapping and Listing Manual GATS Data Management Programmer’s Guide to General Survey System Core Questionnaire Programming Specifications Data Management Implementation Plan Data Management Training Guide GATS Quality Assurance: Guidelines and Documentation GATS Analysis and Reporting Package Fact Sheet Template Country Report: Tabulation Plan and Guidelines Indicator Definitions GATS Data Release and Dissemination Data Release Policy Data Dissemination: Guidance for the Initial Release of the Data Tobacco Questions for Surveys: A Subset of Key Questions from the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) Suggested Citation Global Adult Tobacco Survey Collaborative Group. Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS): Quality Assurance: Guidelines and Documentation, Version 2.0. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010. ii Acknowledgements GATS Collaborating Organizations Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC Foundation Johns Hopkins Bloomberg -

Cigarette Marketing Is More Prevalent in Stores Where Adolescents Shop Frequently L Henriksen, E C Feighery, N C Schleicher, H H Haladjian, S P Fortmann

315 Tob Control: first published as 10.1136/tc.2003.006577 on 25 August 2004. Downloaded from RESEARCH PAPER Reaching youth at the point of sale: cigarette marketing is more prevalent in stores where adolescents shop frequently L Henriksen, E C Feighery, N C Schleicher, H H Haladjian, S P Fortmann ............................................................................................................................... Tobacco Control 2004;13:315–318. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.006577 Objective: Although numerous studies describe the quantity and nature of tobacco marketing in stores, fewer studies examine the industry’s attempts to reach youth at the point of sale. This study examines See end of article for authors’ affiliations whether cigarette marketing is more prevalent in stores where adolescents shop frequently. ....................... Design, setting, and participants: Trained coders counted cigarette ads, products, and other marketing materials in a census of stores that sell tobacco in Tracy, California (n = 50). A combination of data from Correspondence to: Lisa Henriksen, focus groups and in-class surveys of middle school students (n = 2125) determined which of the stores PhD, Stanford Prevention adolescents visited most frequently. Research Center, 211 Main outcome measures: Amount of marketing materials and shelf space measured separately for the Quarry Road, N145, Stanford, CA 94305- three cigarette brands most popular with adolescent smokers and for other brands combined. 5705; Results: Compared to other stores in the same community, stores where adolescents shopped frequently [email protected] contained almost three times more marketing materials for Marlboro, Camel, and Newport, and significantly more shelf space devoted to these brands. Received 3 November 2003 Conclusions: Regardless of whether tobacco companies intentionally target youth at the point of sale, these Accepted 23 May 2004 findings underscore the importance of strategies to reduce the quantity and impact of cigarette marketing ...................... -

ÇUKUROVA ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ DERGİSİ Journal of Çukurova University Institute of Social Sciences

SSN: 1304 – 8880 Çukurova Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Çukurova University Institute of Social Sciences ÇUKUROVA ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ DERGİSİ Journal of Çukurova University Institute of Social Sciences Cilt/ Vol: 25 Sayı/No: 1 Yıl/Year: 2016 ÇUKUROVA ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ DERGİSİ Journal of Çukurova University Institute of Social Sciences Sahibi/Owner Ç.Ü. Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü adına Enstitü Müdürü Prof. Dr. Yıldırım B. ÖNAL Derleyen / Managing Editor Prof. Dr. İ. Çetin DERDİYOK Yayın Kurulu / Board of Editors Prof.Dr. İ. Çetin DERDİYOK (Başkan) Prof.Dr. Hasan KAYIKLIK Prof.Dr. Nurçay TÜRKOĞLU Doç.Dr. Meral KILIÇATICI Doç.Dr. Kemal Can KILIÇ Doç.C. Hakan ÇUHADAR Doç.Dr. Ömer KORKUT Yrd.Doç.Dr. Oya AYGÜN Yrd.Doç.Dr. Fatih GÜLŞEN Derleme Sekreteri / Editorial Secretary Doç.Dr. Kemal Can KILIÇ Dizgi-Mizanpaj / Typesetter Seren YOKSULABAKAN Copyright©Nisan 2016 Çukurova Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi Tüm hakları mahfuzdur. TÜBİTAK / ULAKBİM Sosyal Bilimler Veri Tabanına (SBVT) dâhildir. Dergimiz EBSCO-CEEAS veri tabanında taranmaktadır. Çukurova Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi yılda en az 2 kez yayımlanan hakemli bir dergidir. Dergide yayımlanan makalelerin dil ve bilim sorumluluğu yazara aittir. Makaleler kaynak gösterilmeden kullanılamaz. Elektronik veya mekanik yöntemlerle (fotokopi dahil) herhangi biçimde basılamaz ve / veya çoğaltılamaz. Adres / Address: ÇÜ. Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Müdürlüğü 01330 Balcalı / ADANA Tel: 0 (322) 338 65 74 Faks: 0 (322) 338 69 47 E- Posta: [email protected] İnternet adresi: http://sosyalbilimler.cu.edu.tr Kapak Tasarımı: Metin AYGÜN Baskı: Çukurova Üniversitesi Danışma Kurulu /Advisory Board Prof. Dr. Abdullatif ACARLIOĞLU Anadolu Üniversitesi Prof. Dr. Gül DURMUŞOĞLU KÖSE Anadolu Üniversitesi Prof. -

External Sites

2011 NATIONAL SURVEY ON DRUG USE AND HEALTH GENERAL PRINCIPLES AND PROCEDURES FOR EDITING DRUG USE DATA IN THE 2011 NSDUH COMPUTER-ASSISTED INTERVIEW Prepared for the 2011 Methodological Resource Book Contract No. HHSS283200800004C RTI Project No. 0211838.207.003 Deliverable No. 39 Authors: Project Director: Larry A. Kroutil Thomas G. Virag Wafa Handley Michael R. Bradshaw Prepared for: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Rockville, Maryland 20857 Prepared by: RTI International Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709 January 2013 2011 NATIONAL SURVEY ON DRUG USE AND HEALTH GENERAL PRINCIPLES AND PROCEDURES FOR EDITING DRUG USE DATA IN THE 2011 NSDUH COMPUTER-ASSISTED INTERVIEW Prepared for the 2011 Methodological Resource Book Contract No. HHSS283200800004C RTI Project No. 0211838.207.003 Deliverable No. 39 Authors: Project Director: Larry A. Kroutil Thomas G. Virag Wafa Handley Michael R. Bradshaw Prepared for: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Rockville, Maryland 20857 Prepared by: RTI International Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709 January 2013 Acknowledgments This report was developed for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (CBHSQ, formerly the Office of Applied Studies), by RTI International (a trade name of Research Triangle Institute), Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, under Contract No. HHSS283200800004C. At RTI, Larry A. Kroutil, Wafa Handley, and Michael R. Bradshaw co-authored this report. Significant contributors at RTI listed alphabetically include Chuchun Chien, Barbara J. Felts, and Thomas G. Virag (Project Director). Richard S. Straw copyedited the document, and Debbie Bond word processed it. DISCLAIMER SAMHSA provides links to other Internet sites as a service to its users and is not responsible for the availability or content of these external sites. -

WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation

WHO Technical Report Series 1001 WHO study group on tobacco product regulation Report on the scientific basis of tobacco product regulation: Sixth report of a WHO study group The World Health Organization was established in 1948 as a specialized agency of the United Nations serving as the directing and coordinating authority for international health matters and public health. One of WHO’s constitutional functions is to provide objective and reliable information and advice in the field of human health, a responsibility that it fulfils in part through its extensive programme of publications. The Organization seeks through its publications to support national health strategies and address the most pressing public health concerns of populations around the world. To respond to the needs of Member States at all levels of development, WHO publishes practical manuals, handbooks and training material for specific categories of health workers; internationally applicable guidelines and standards; reviews and analyses of health policies, programmes and research; and state-of-the-art consensus reports that offer technical advice and recommendations for decision-makers. These books are closely tied to the Organization’s priority activities, encompassing disease prevention and control, the development of equitable health systems based on primary health care, and health promotion for individuals and communities. Progress towards better health for all also demands the global dissemination and exchange of information that draws on the knowledge and experience of all WHO’s Member countries and the collaboration of world leaders in public health and the biomedical sciences. To ensure the widest possible availability of authoritative information and guidance on health matters, WHO secures the broad international distribution of its publications and encourages their translation and adaptation. -

Informatie Over Lot, Op Te Nemen Op Blz

From Text to Talk Answers and their uptake in standardised survey interviews Published by LOT phone: +31 30 253 6006 Janskerkhof 13 fax: +31 30 253 6000 3512 BL Utrecht e-mail: [email protected] The Netherlands http://wwwlot.let.uu.nl/ Cover illustration: New Connections by S. Unger ISBN-10: 90-78328-08-8 ISBN-13: 978-90-78328-08-7 NUR 632 Copyright © 2006: Sanne van ‘t Hof. All rights reserved. From Text to Talk Answers and their uptake in standardised survey interviews Van Tekst naar Gesprek Antwoorden en hun ontvangst in gestandaardiseerde survey interviews (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de Rector Magnificus, Prof. Dr. W.H. Gispen, ingevolge het besluit van het College voor Promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op vrijdag 6 oktober 2006 des ochtends te 10.30 uur door SANNE VAN ‘T HOF geboren op 24 juli 1976 te Middelburg Promotores: Prof. Dr. Mr. P.J. van de Hoven Faculteit der Letteren Universiteit Utrecht Prof. Dr. W.P. Drew Sociology Department University of York Co-promotor: Dr. A.J. Koole Faculteit der Letteren Universiteit Utrecht Table of contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................... 9 1.1 Opening statement ........................................................9 1.2 Survey research...........................................................10 1.3 The theory of survey research......................................17 -

Measuring Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products Suggested Citation: Stoklosa M., Paraje G., Blecher E., a Toolkit on Measuring Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products

tobacconomics Economic Research Informing Tobacco Control Policy A Toolkit on Measuring Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products Suggested Citation: Stoklosa M., Paraje G., Blecher E., A Toolkit on Measuring Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products. A Tobacconomics and American Cancer Society Toolkit. Chicago, IL: Tobacconomics, Health Policy Center, Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago, 2020. www.tobacconomics.org Authors: This Toolkit was written by Michal Stoklosa, PhD, American Cancer Society, Atlanta, United States; Guillermo Paraje, PhD, Professor, Business School, Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez, Santiago, Chile; and Evan Blecher, PhD, Senior Economist, Health Policy Center, University of Illinois at Chicago. It was peer-reviewed by Roberto Iglesias, PhD, Technical Officer, Fiscal Policies for Health, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland; and Hana Ross, PhD, Principal Research Officer, Research Unit on the Economics of Excisable Products, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa. This Toolkit was funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies. About Tobacconomics: Tobacconomics is a collaboration of leading researchers who have been studying the economics of tobacco control policy for nearly 30 years. The team is dedicated to helping researchers, advocates, and policy makers access the latest and best research about what’s working—or not working—to curb tobacco consumption and its economic impacts. As a program of the University of Illinois at Chicago, Tobacconomics is not affiliated with any tobacco manufacturer. Visit www.tobacconomics.org or follow us on Twitter www.twitter.com/tobacconomics . About Economic and Health Policy Research (EHPR): The EHPR program at the American Cancer Society seeks to address cancer worldwide by conducting research on the economic and policy aspects of risk factors to cancer. -

Tobacco Control Survey, England 2016/17

www.tradingstandards.uk TOBACCO CONTROL SURVEY, ENGLAND 2016/17 A report of council trading standards service activity By Jane MacGregor, MacGregor Consulting Limited and Liz Spratt for the Chartered Trading Standards Institute 1 Tobacco Control Survey, England 2016/17: A report of council trading standards service activity Contents 2 Contents 4 Summary 9 1 Introduction 10 2 Methodology 11 3 Tobacco control activities 12 4 Underage sales activity 18 5 Actions taken in relation to the Children and Young Persons Act 1933 (as amended) 20 6 Underage sales activity – nicotine inhaling products (NIPs) 26 7 Actions taken in relation to a breach of the Children and Families Act 2014 28 8 Illicit tobacco products 38 9 Display and pricing of tobacco products 41 10 Tobacco and Related Products Regulations 2016 (TRP) 44 11 Standardised Packaging of Tobacco Products Regulations 2015 (SPoT) 46 12 Article 5.3 of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control 49 13 Conclusion 51 Annex 1: Underage sales of tobacco products – definitions of premises types 51 Annex 2: Underage sales of NIPs – definitions of premises types 52 Annex 3: Illicit tobacco definitions Main report: tables 10 Table 1: Response rate by council type 10 Table 2: Response rate by region 13 Table 3: Proportion of complaints and enquiries received by premises type 14 Table 4: Proportion of visits by trading standards officers by premises type 17 Table 5: Percentage of visits undertaken by volunteer young persons by premises type 17 Table 6: Proportion of visits resulting in illegal sales -

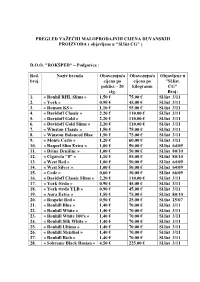

PREGLED VAŽEĆIH MALOPRODAJNIH CIJENA DUVANSKIH PROIZVODA ( Objavljene U "Sl.List CG" )

PREGLED VAŽEĆIH MALOPRODAJNIH CIJENA DUVANSKIH PROIZVODA ( objavljene u "Sl.list CG" ) D.O.O. "ROKŠPED" – Podgorica : Red. Naziv brenda Obavezujuća Obavezujuća Objavljene u broj. cijena po cijena po "Sl.list. paklici – 20 kilogramu CG" cig. Broj: 1. « Ronhil RHL Slims » 1,50 € 75,00 € Sl.list 3/11 2. « York » 0,90 € 45,00 € Sl.list 3/11 3. « Ronson KS » 1,10 € 55,00 € Sl.list 3/11 4. « Davidoff Classic » 2,20 € 110,00 € Sl.list 3/11 5. « Davidoff Gold » 2,20 € 110,00 € Sl.list 3/11 6. « Davidoff Gold Slims » 2,20 € 110,00 € Sl.list 3/11 7. « Winston Classic » 1,50 € 75,00 € Sl.list 3/11 8. « Winston Balanced Blue 1,50 € 75,00 € Sl.list 3/11 9. « Monte Carlo » 1,20 € 60,00 € Sl.list 3/11 10. « Raquel Slim Extra » 1,00 € 50,00 € Sl.list 64/09 11. « Drina Denifine » 1,00 € 50,00 € Sl.list 80/10 12. « Cigareta "8" » 1,10 € 55,00 € Sl.list 80/10 13. « West Red » 1,00 € 50,00 € Sl.list 64/09 14. « West Silver » 1,00 € 50,00 € Sl.list 64/09 15. « Code » 0,60 € 30,00 € Sl.list 66/09 16. « Davidoff Classic Slims » 2,20 € 110,00 € Sl.list 3/11 17. « York tvrdo » 0,90 € 45,00 € Sl.list 3/11 18. « York tvrdo YLB » 0,90 € 45,00 € Sl.list 3/11 19. « Aura Extra » 1,50 € 75,00 € Sl.list 80/10 20. « Respekt Red » 0,50 € 25,00 € Sl.list 25/07 21.