Trade Mark Inter-Partes Decision O/162/09

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imperial Tobacco Australia Limited

Imperial Tobacco Australia Limited Submission to the House Standing Committee on Health and Ageing regarding the Inquiry into Plain Tobacco Packaging 22 July 2011 www.imperial-tobacco.com An IMPERIAL TOBACCO GROUP company Registered Office: Level 4, 4-8 Inglewood Place, Norwest Business Park, Baulkham Hills NSW 2153 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 2 COMPANY BACKGROUND 6 3 NO CREDIBLE RESEARCH TO SUPPORT THE INTRODUCTION OF PLAIN PACKAGING 7 4 INCREASED TRADE IN ILLICIT TOBACCO 10 4.1 Combating counterfeit product 11 4.2 Illicit trade impact from unproven regulations 14 4.3 Plain Packaging is not an FCTC obligation 15 4.4 Plain Packaging will place Australia in breach of FCTC obligations 16 5 PLAIN PACKAGING WILL BREACH THE LAW AND INTERNATIONAL TREATIES 19 5.1 Specific Breaches of the TRIPS Agreement 20 5.2 Plain Packaging will breach the Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade 25 5.3 Breaches of Free Trade Agreements and Bilateral Investment Treaties 27 5.4 Threat to Australia’s reputation 28 6 THE BILL IS UNCONSTITUTIONAL 29 7 NEGATIVE IMPACT ON COMPETITION, CONSUMERS AND RETAILERS 32 7.1 Adverse effects on consumers and retailers 32 7.2 Known effects on businesses and retailers 34 8 INADEQUATE TIME FOR COMPLIANCE 36 8.1 Uncertainty created by incomplete draft Regulations 38 8.2 Previous timelines at introduction of Graphic Health Warnings 2005/6 40 8.3 The Bill and draft Regulations omit important consumer information 41 8.4 Strict Liability and Criminal Penalties 42 9 AUSTRALIA the “NANNY STATE” 43 9.1 Over regulation 43 -

Answers and Their Uptake in Standardised Survey Interviews

From Text to Talk Answers and their uptake in standardised survey interviews Published by LOT phone: +31 30 253 6006 Janskerkhof 13 fax: +31 30 253 6000 3512 BL Utrecht e-mail: [email protected] The Netherlands http://wwwlot.let.uu.nl/ Cover illustration: New Connections by S. Unger ISBN-10: 90-78328-08-8 ISBN-13: 978-90-78328-08-7 NUR 632 Copyright © 2006: Sanne van ‘t Hof. All rights reserved. From Text to Talk Answers and their uptake in standardised survey interviews Van Tekst naar Gesprek Antwoorden en hun ontvangst in gestandaardiseerde survey interviews (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de Rector Magnificus, Prof. Dr. W.H. Gispen, ingevolge het besluit van het College voor Promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op vrijdag 6 oktober 2006 des ochtends te 10.30 uur door SANNE VAN ‘T HOF geboren op 24 juli 1976 te Middelburg Promotores: Prof. Dr. Mr. P.J. van de Hoven Faculteit der Letteren Universiteit Utrecht Prof. Dr. W.P. Drew Sociology Department University of York Co-promotor: Dr. A.J. Koole Faculteit der Letteren Universiteit Utrecht Table of contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................... 9 1.1 Opening statement ........................................................9 1.2 Survey research...........................................................10 1.3 The theory of survey research......................................17 -

Point-Of-Sale: Tobacco Industry's Last Domain to Fight Bans

POINT‐OF‐SALE: TOBACCO INDUSTRY’S LAST DOMAIN TO FIGHT BANS ON ADVERTISING AND PROMOTIONS Introduction With tobacco advertising and promotions being either totally or partially banned in the mass media in ASEAN, the tobacco industry has shifted its focus to the point-of-sale (POS), it is now the principal avenue for marketing and promoting cigarettes, particularly to vulnerable minors. Cigarette displays at POS are aimed at keeping cigarettes visible and normalizing the product in the public’s mind. POS outlets are ubiquitous, and there is usually no control over their numbers as well as no regulations over what can be sold, which gives the tobacco industry an easy way to make cigarettes easily available. Most countries in the region allow cigarette advertising and promotions at POS. The Philippines and Thailand are licensing the POS outlets. And Thailand is the only ASEAN country that has a comprehensive ban of tobacco industry advertising and promotions at POS that includes a ban of cigarette packs display. Cigarette packs and cartons must be hidden under the cashier’s counter and its display rack and shelves must be covered. SURVEILLANCE Country Current Remarks law/regulation on POS Cambodia Partial ban Enforcement starts in August 2011 Except pack display Indonesia Partial ban Except pack display Lao PDR Partial ban Except pack display INDUSTRY Malaysia Partial ban Except pack display Philippines Partial ban Except pack display Thailand Comprehensive ban Vietnam Partial ban Allows display of only 1 pack or 1 carton per brand Regional industry tactics and trends in POS TOBACCO Marketing channels Cigarettes are sold in POS such as supermarkets, sundry shops, kiosks, newsstands, mobile vans, street vendors, market stalls, minimarts and convenience stores. -

Smoking and Quitting Behaviour in Lockdown South Africa

SMOKING AND QUITTING BEHAVIOUR IN LOCKDOWN SOUTH AFRICA: RESULTS FROM A SECOND SURVEY Professor Corné van Walbeek Samantha Filby Kirsten van der Zee 21 July 2020 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report is based on the results of an online survey, conducted between 4 June and 19 June 2020. The study was conducted by the Research Unit on the Economics of Excisable Products (REEP), an independent research unit based at the University of Cape Town. It was funded by the African Capacity Building Foundation, which in turn is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. This report follows on from our first report entitled “Lighting up the illicit cigarette market: Smokers’ responses to the cigarette sales ban in South Africa”, which was published on 15 May 2020. That report was based on an online survey conducted between 29 April and 11 May 2020. When the second survey was conducted, the ban on the sales of cigarettes had been extended, even as the country had moved from lockdown Level 4 to Level 3. The questionnaire was distributed on Twitter, Change.org (a petition site) and Moya (a data-free platform). The survey yielded 23 631 usable responses. In contrast to the first study, we did not weigh the data, because the sampling methodology (i.e. online survey) made it impossible to reach the poorer segments of society. We thus do not claim that the data is nationally representative; we report on the characteristics of the sample, not the South African smoking population. In the report we often report the findings by race and gender, because smoking behaviour in South Africa has very pronounced race-gender differences. -

Menthol Content in U.S. Marketed Cigarettes

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Nicotine Manuscript Author Tob Res. Author Manuscript Author manuscript; available in PMC 2017 July 01. Published in final edited form as: Nicotine Tob Res. 2016 July ; 18(7): 1575–1580. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntv162. Menthol Content in U.S. Marketed Cigarettes Jiu Ai, Ph.D.1, Kenneth M. Taylor, Ph.D.1, Joseph G. Lisko, M.S.2, Hang Tran, M.S.2, Clifford H. Watson, Ph.D.2, and Matthew R. Holman, Ph.D.1 1Office of Science, Center for Tobacco Products, United States Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD 20993 2Tobacco Products Laboratory, National Center for Environmental Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA Abstract Introduction—In 2011 menthol cigarettes accounted for 32 percent of the market in the United States, but there are few literature reports that provide measured menthol data for commercial cigarettes. To assess current menthol application levels in the U.S. cigarette market, menthol levels in cigarettes labeled or not labeled to contain menthol was determined for a variety of contemporary domestic cigarette products. Method—We measured the menthol content of 45whole cigarettes using a validated gas chromatography/mass spectrometry method (GC/MS). Results—In 23 cigarette brands labeled as menthol products, the menthol levels of the whole cigarette ranged from 2.9 to 19.6 mg/cigarette, with three products having higher levels of menthol relative to the other menthol products. The menthol levels for 22 cigarette products not labeled to contain menthol ranged from 0.002 to 0.07 mg/cigarette. -

Guidance Document for Administrating the Alaska Native Adult Tobacco Survey

GUIDANCE DOCUMENT Administrating the Alaska Native Adult Tobacco Survey Guidance Document for Administrating the Alaska Native Adult Tobacco Survey Art for front cover: Sierra Gerlach, Health Education and Promotion Council, Inc., 2433 W. Chicago, Suite C, Rapid City, SD 57702 Authors: Victoria A. Albright, MA1 Adriane Niare, MPH, CHES2 Sara Mirza, MPH2 Stacy L. Thorne, PhD, MPH, CHES2 Ralph S. Caraballo, PhD, MPH2 1 RTI International 2 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center of Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, Epidemiology Branch Acknowledgments: Alaska Native Health Board, Anchorage, AK Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, Anchorage, AK Alaska Native Adult Tobacco Survey Coordinator: St. Paul and Unalaska, AK Alaska Native Adult Tobacco Survey Interviewers: St. Paul and Unalaska, AK Alaska Native Adult Tobacco Survey Participants: St. Paul and Unalaska, AK Arctic Slope Native Corporation, Barrow, AK Maniilaq Health Center, Kotzebue, AK Norton Sound Health Corporation, Nome, AK Rita Anniskett Daria Dirks Alyssa Easton, PhD, MPH Jenny Jennings Foerst, PhD Andrea Fenaughty, PhD Nick Gonzales Charlotte Gisvold Corrine Husten, MD, MPH Doreen O. Lacy Brick Lancaster, MA, CHES Barbara Parks, RDH, MPH Jay Macedo, MA Brenna Muldavin, MS Trena Rairdon Loreano Reano, MPA Laura Revels Caroline C Renner Cynthia Tainpeah, RN Ray Tainpeah, MEd, LADC Janis Weber, PhD Suggested citation: Albright VA, Mirza S, Caraballo R, Niare A, Thorne SL. Guidance document for administrating the Alaska Native Adult Tobacco Survey. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010. _________________________________ RTI International is a trade name of Research Triangle Institute. -

Kohl's Corporation 12 March 2021 Dear Ms. Michelle Gass, We Have the Honour to Address You in Our Capacities As Working Group On

PALAIS DES NATIONS • 1211 GENEVA 10, SWITZERLAND Mandates of the Working Group on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises; the Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights; the Special Rapporteur on minority issues; the Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief; the Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of slavery, including its causes and consequences; the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment; and the Special Rapporteur on trafficking in persons, especially women and children REFERENCE: AL OTH 118/2021 12 March 2021 Dear Ms. Michelle Gass, We have the honour to address you in our capacities as Working Group on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises; Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights; Special Rapporteur on minority issues; Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief; Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of slavery, including its causes and consequences; Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment; and Special Rapporteur on trafficking in persons, especially women and children, pursuant to Human Rights Council resolutions 44/15, 37/12, 43/8, 40/10, 42/10, 43/20 and 44/4. We are independent human rights experts appointed and mandated by the United Nations Human Rights Council to report and advise on human rights issues from a thematic or country-specific perspective. We are part of the special procedures system of the United Nations, which has 56 thematic and country mandates on a broad range of human rights issues. -

MS in Focus 6 Intimacy and Sexuality English

MS MSin in Focus focus IssueIssue One •• 2003 2002 Issue 6 • 2005 ● Intimacy and Sexuality The Magazine of the Multiple Sclerosis International Federation 1 MSin focus Issue 6 • 2005 Editorial Board Executive Editor Nancy Holland, EdD, RN, MSCN, Vice Multiple Sclerosis President, Clinical Programs and Professional Resource International Federation Centre, National Multiple Sclerosis Society USA. Editor and Project Leader Michele Messmer Uccelli, BA, MSIF is a unique collaboration of national MS MSCS, Department of Social and Health Research, Italian societies and the international scientific Multiple Sclerosis Society, Genoa, Italy. community. Managing Editor Helle Elisabeth Lyngborg, Information It leads the global MS movement in sharing and Communications Manager, Multiple Sclerosis best practice to significantly improve the International Federation. quality of life of people affected by MS and in Editorial Assistant Chiara Provasi, MA, Project Co- stimulating research into the understanding ordinator, Department of Social and Health Research, Italian and treatment of the condition. Multiple Sclerosis Society, Genoa, Italy. Our priorities are: MSIF Responsible Board Member • Stimulating global research Prof Dr Jürg Kesselring, Chair of MSIF International Medical • Stimulating the active exchange of and Scientific Board, Head of the Department of Neurology, information Rehabilitation Centre, Valens, Switzerland. • Providing support for the development of Editorial Board Members new and existing MS societies Guy Ganty, Head of the Speech and Language Pathology • Advocacy Department, National Multiple Sclerosis Centre, Melsbroek, Belgium. All of our work is carried out with the complete involvement of people living Katrin Gross-Paju, PhD, Estonian Multiple Sclerosis Centre, with MS. West Tallinn Central Hospital, Tallinn, Estonia. Marco Heerings, RN, MA, MSCN, Nurse Practitioner, Designed and produced by Groningen University Hospital, Groningen, The Netherlands. -

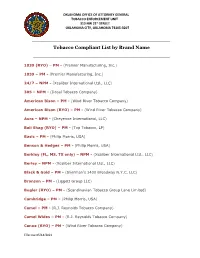

Tobacco Compliant List by Brand Name ______

OKLAHOMA OFFICE OF ATTORNEY GENERAL TOBACCO ENFORCEMENT UNIT 313 NW 21st STREET OKLAHOMA CITY, OKLAHOMA 73105-3207 _____________________________________________________________________________ Tobacco Compliant List by Brand Name _________________________________________ 1839 (RYO) – PM - (Premier Manufacturing, Inc.) 1839 – PM - (Premier Manufacturing, Inc.) 24/7 – NPM - (Xcaliber International Ltd., LLC) 305 – NPM - (Dosal Tobacco Company) American Bison – PM - (Wind River Tobacco Company) American Bison (RYO) – PM - (Wind River Tobacco Company) Aura – NPM - (Cheyenne International, LLC) Bali Shag (RYO) – PM - (Top Tobacco, LP) Basic – PM - (Philip Morris, USA) Benson & Hedges – PM - (Philip Morris, USA) Berkley (FL, MS, TX only) – NPM - (Xcaliber International Ltd., LLC) Berley – NPM - (Xcaliber International Ltd., LLC) Black & Gold – PM - (Sherman’s 1400 Broadway N.Y.C. LLC) Bronson – PM - (Liggett Group LLC) Bugler (RYO) – PM - (Scandinavian Tobacco Group Lane Limited) Cambridge – PM – (Philip Morris, USA) Camel – PM - (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company) Camel Wides – PM - (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company) Canoe (RYO) – PM - (Wind River Tobacco Company) Effective 05/14/2021 Capri – PM - (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company) Carlton – PM - (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company) Carnival – NPM - (KT&G Corporation) Chesterfield – PM - (Philip Morris, USA) Cheyenne – NPM - (Cheyenne International, LLC) Cigarettellos – PM - (Sherman’s 1400 Broadway N.Y.C. LLC) Classic – PM - (Sherman’s 1400 Broadway N.Y.C. LLC) Commander – PM - (Philip Morris, USA) Crowns – PM - (Commonwealth Brands, Inc.) DTC – NPM - (Dosal Tobacco Company) Dave’s – PM - (Philip Morris, USA) Decade – NPM - (Cheyenne International, LLC) Doral – PM - (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company) Drum (RYO) – PM - (Top Tobacco, LP) Dunhill International – PM - (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company) Dunhill – PM - (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company) Eagle 20's – PM - (Liggett Group LLC) * Vector Tobacco Inc. -

Vaping and E-Cigarettes: Adding Fuel to the Coronavirus Fire?

Vaping and e-cigarettes: Adding fuel to the coronavirus fire? abcnews.go.com/Health/vaping-cigarettes-adding-fuel-coronavirus-fire/story By Dr. Chloë E. Nunneley 26 March 2020, 17:04 6 min read Vaping and e-cigarettes: Adding fuel to the coronavirus fire?Because vaping can cause dangerous lung and respiratory problems, experts say it makes sense that the habit could aggravate the symptoms of COVID-19. New data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention last week warns that young people may be more impacted by COVID-19 than was initially thought, with patients under the age of 45 comprising more than a third of all cases, and one in five of those patients requiring hospitalization. Although scientists still don’t have good data to explain exactly why some young people are getting very sick from the novel coronavirus, some experts are now saying that the popularity of e-cigarettes and vaping could be making a bad situation even worse. Approximately one in four teens in the United States vapes or smokes e-cigarettes, with the FDA declaring the teenage use of these products a nationwide epidemic and the CDC warning about a life-threatening vaping illness called EVALI, or “E-cigarette or Vaping- Associated Lung Injury.” Public health experts believe that conventional cigarette smokers are likely to have more serious illness if they become infected with COVID-19, according to the World Health Organization. Because vaping can also cause dangerous lung and respiratory problems, 1/4 experts say it makes sense that the habit could aggravate the symptoms of COVID-19, although they will need longer-term studies to know for sure. -

Quality Assurance: Guidelines and Documentation

GTSS Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) GLOBAL TOBACCO SURVEILLANCE SYSTEM (GTSS) Quality Assurance: Guidelines and Documentation Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) Quality Assurance: Guidelines and Documentation Version 2.0 November 2010 Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) Comprehensive Standard Protocol ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… GATS Questionnaire Core Questionnaire with Optional Questions Question by Question Specifications GATS Sample Design Sample Design Manual Sample Weights Manual GATS Fieldwork Implementation Field Interviewer Manual Field Supervisor Manual Mapping and Listing Manual GATS Data Management Programmer’s Guide to General Survey System Core Questionnaire Programming Specifications Data Management Implementation Plan Data Management Training Guide GATS Quality Assurance: Guidelines and Documentation GATS Analysis and Reporting Package Fact Sheet Template Country Report: Tabulation Plan and Guidelines Indicator Definitions GATS Data Release and Dissemination Data Release Policy Data Dissemination: Guidance for the Initial Release of the Data Tobacco Questions for Surveys: A Subset of Key Questions from the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) Suggested Citation Global Adult Tobacco Survey Collaborative Group. Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS): Quality Assurance: Guidelines and Documentation, Version 2.0. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010. ii Acknowledgements GATS Collaborating Organizations Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC Foundation Johns Hopkins Bloomberg -

Cigarette Marketing Is More Prevalent in Stores Where Adolescents Shop Frequently L Henriksen, E C Feighery, N C Schleicher, H H Haladjian, S P Fortmann

315 Tob Control: first published as 10.1136/tc.2003.006577 on 25 August 2004. Downloaded from RESEARCH PAPER Reaching youth at the point of sale: cigarette marketing is more prevalent in stores where adolescents shop frequently L Henriksen, E C Feighery, N C Schleicher, H H Haladjian, S P Fortmann ............................................................................................................................... Tobacco Control 2004;13:315–318. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.006577 Objective: Although numerous studies describe the quantity and nature of tobacco marketing in stores, fewer studies examine the industry’s attempts to reach youth at the point of sale. This study examines See end of article for authors’ affiliations whether cigarette marketing is more prevalent in stores where adolescents shop frequently. ....................... Design, setting, and participants: Trained coders counted cigarette ads, products, and other marketing materials in a census of stores that sell tobacco in Tracy, California (n = 50). A combination of data from Correspondence to: Lisa Henriksen, focus groups and in-class surveys of middle school students (n = 2125) determined which of the stores PhD, Stanford Prevention adolescents visited most frequently. Research Center, 211 Main outcome measures: Amount of marketing materials and shelf space measured separately for the Quarry Road, N145, Stanford, CA 94305- three cigarette brands most popular with adolescent smokers and for other brands combined. 5705; Results: Compared to other stores in the same community, stores where adolescents shopped frequently [email protected] contained almost three times more marketing materials for Marlboro, Camel, and Newport, and significantly more shelf space devoted to these brands. Received 3 November 2003 Conclusions: Regardless of whether tobacco companies intentionally target youth at the point of sale, these Accepted 23 May 2004 findings underscore the importance of strategies to reduce the quantity and impact of cigarette marketing ......................