The Dome of the Rock As Palimpsest: {Abd Al-Malik's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where Did Solomon Build the Temple? by Dr

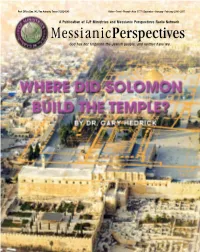

Post Office Box 345, San Antonio, Texas 78292-0345 Kislev –Tevet– Shevat–Adar 5777 / December– January– February 2016–2017 A Publication of CJF Ministries and Messianic Perspectives Radio Network MessianicPerspectives ® God has not forgotten the Jewish people, and neither have we. e are living in tumultuous times. Many things that Historical Background Wwe’ve always taken for granted are being called into question. The people of Israel had three central places of worship in ancient times: the Tabernacle, the First Temple, and the One hotly-disputed question these days is, “Were the an- Second Temple. Around 538 BC, the Jewish captives were cient Temples really on the Temple Mount?” You’d think released by King Cyrus of Persia to return from exile to the fact that Mount Moriah (and the manmade plat- their Land. Zerubbabel and Joshua the priest led the ef- form around it) has been known for many centuries as fort to rebuild the Second Temple, and work commenced “the Temple Mount”1 would provide an important clue, around 536 BC on the site of the First Temple, which the wouldn’t you? Babylonians had destroyed. The new Temple was simpler and more modest than its impressive predecessor had It’s a bit like the facetious query about who’s buried in been.2 Centuries later, when Yeshua sat contemplatively Grant’s tomb. Who else would be in that tomb but Mr. on the Mount of Olives with His disciples (Matt. 24), they Grant and what else would have been on the Temple looked down on the Temple Mount as King Herod’s work- Mount but the Temple? ers were busily at work remodeling and expanding the But not everyone agrees. -

By Celeste Gianni History of Libraries in the Islamic World: a Visual Guide

History of Libraries in the Islamic World: A Visual Guide by Celeste Gianni History of Libraries in the Islamic World: A Visual Guide by Celeste Gianni Published by Gimiano Editore Via Giannone, 14, Fano (PU) 61032 ©Gimiano Editore, 2016 All rights reserved. Printed in Italy by T41 B, Pesaro (PU) First published in 2016 Publication Data Gianni, Celeste History of Libraries in the Islamic World: A Visual Guide ISBN 978 88 941111 1 8 CONTENTS Preface 7 Introduction 9 Map 1: The First Four Caliphs (10/632 - 40/661) & the Umayyad Caliphate (40/661 - 132/750) 18 Map 2: The ʿAbbasid Caliphate (132/750 - 656/1258) 20 Map 3: Islamic Spain & North African dynasties 24 Map 4: The Samanids (204/819 - 389/999), the Ghaznavids (366/977 - 558/1163) and the Safavids (906/1501 - 1148/1736) 28 Map 5: The Buyids (378/988 - 403/1012) 30 Map 6: The Seljuks (429/1037 - 590/1194) 32 Map 7: The Fatimids (296/909 - 566/1171) 36 Map 8: The Ayyubids (566/1171 - 658/1260) 38 Map 9: The Mamluks (470/1077 - 923/1517) 42 Map 10: After the Mongol Invasion 8th-9th/14th - 15th centuries 46 Map 11: The Mogul Empire (932/1526 - 1273/1857) 48 Map 12: The Ottoman Empire (698/1299 - 1341/1923) up to the 12th/18th century. 50 Map 13: The Ottoman Empire (698/1299 - 1341/1923) from 12th/18th to the 14th/20th century. 54 Bibliography 58 PREFACE This publication is very much a basic tool intended to help different types of libraries by date, each linked to a reference so that researchers working in the field of library studies, and in particular the it would be easier to get to the right source for more details on that history of library development in the Islamic world or in comparative library or institution. -

Scholars, Chroniclers, and Jerusalem Archivists

Palestine in the Nineteenth Century Library (no. 963 in the catalogue) sources, and its members may be written by a certain Muhammad put forth confidently as the direct Scholars, Chroniclers, ibn `Abd al-Rahman ibn `Abd ancestors of the modern family. al-`Aziz al-Khalidi who, as we can The series begins with Shams deduce from internal evidence, lived al-Din Muhammad ibn `Abdullah in the mid-eleventh century, and al-`Absi al-Dayri al-Maqdisi who and Jerusalem most probably before the Crusader was born in Jerusalem around 1343 occupation of the city in 1099. We and died there on November 2, know that this occupation caused 1424. His father was a merchant, a mass exodus from Jerusalem, originally from a Nablus district Archivists scattering its families in all called al-Dayr. Encouraged by directions. A family tradition has it his father, Muhammad studied in A History of the Khalidis that the Khalidis sought refuge in Jerusalem, Damascus, and Cairo the village of Dayr `Uthman, in the and then became a Hanafite mufti province of Nablus and returned to of Jerusalem and a distinguished Jerusalem after Saladin recaptured scholar and teacher. the city on October 2, 1187. When Two of Muhammad’s five sons they came back, they were known achieved the same renown as as Dayris or Dayri/Khalidis, but this their father: Sa`d al-Din Sa`d who remains a mere possibility because it was born in Jerusalem in 1367 is unattested in the sources. he history of families is a and died in Cairo in 1463 and notoriously difficult subject. -

Israel and Judah: 18. Temple Interior and Dedication

Associates for Scriptural Knowledge • P.O. Box 25000, Portland, OR 97298-0990 USA © ASK, March 2019 • All rights reserved • Number 3/19 Telephone: 503 292 4352 • Internet: www.askelm.com • E-Mail: [email protected] How the Siege of Titus Locates the Temple Mount in the City of David by Marilyn Sams, July 2016 Formatted and annotated by David Sielaff, March 2019 This detailed research paper by independent author Marilyn Sams is one of several to follow her 2015 book, The Jerusalem Temple Mount Myth. Her book was inspired by a desire to prove (or disprove) Dr. Ernest Martin’s research in The Temples That Jerusalem Forgot. Ms. Sams wrote a second book in 2017, The Jerusalem Temple Mount: A Compendium of Ancient Descriptions expanding the argument in her first book, itemizing and analyzing 375 ancient descriptions of the Temple, Fort Antonia, and environs, all confirming a Gihon location for God’s Temples.1 Her books and articles greatly advance Dr. Martin’s arguments. David Sielaff, ASK Editor Marilyn Sams: The siege of Titus has been the subject of many books and papers, but always from the false perspective of the Jerusalem Temple Mount’s misidentification.2 The purpose of this paper is to illuminate additional aspects of the siege, in order to show how they cannot reasonably be applied to the current models of the temple and Fort Antonia, but can when the “Temple Mount” is identified as Fort Antonia. Conflicts Between the Rebellious Leaders Prior to the Siege of Titus A clarification of the definition of “Acra” is crucial to understanding the conflicts between John of Gischala and Simon of Giora, two of the rebellious [Jewish] faction leaders, who divided parts of Jerusalem 1 Her second book shows the impossibility of the so-called “Temple Mount” and demonstrate the necessity of a Gihon site of the Temples. -

Chapter 3 Translatio Templi: a Conceptual Condition for Jerusalem References in Medieval Scandinavia

Eivor Andersen Oftestad Chapter 3 Translatio Templi: A Conceptual Condition for Jerusalem References in Medieval Scandinavia The present volume traces Jerusalem references in medieval Scandinavia. An impor- tant condition for these references is the idea of Christians’ continuity with the bibli- cal Jerusalem and the Children of Israel. Accordingly, as part of an introduction to the topic, an explanation of this idea is useful and is given in the following. According to the Bible, God revealed himself to the Jews and ordered a house to be built for his dwelling among his people.1 The high priest was the only one allowed to enter His presence in the innermost of the Temple – the Holy of Holies was the exclusive meeting place between God and man. This was where the Ark of the Covenant was preserved, and it was the place for the offering at the Atonement day. The Old Testament temple cult is of fundamental significance for the legitimation of the Christian Church. Although this legitimation has always depended on the idea of continuity between Jewish worship and Christian worship, the continuity has been described variously throughout history. To the medieval Church, a transfer of both divine presence and sacerdotal authority from the Old to the New Covenant was crucial. At the beginning of the twelfth century, which was both in the wake of the first crusade and the period when the Gregorian papacy approved the new Scandinavian Church province, a certain material argument of continuity occurred in Rome that can be described according to a model of translatio templi.2 The notion of translatio can be used to characterize a wide range of phenomena and has been one of several related approaches to establish continuity over time in western history.3 The “translation of the empire,” translatio imperii, was defined by 1 1 Kgs 6:8. -

Nur Al-Din, the Qastal Al-Shu{Aybiyya, and the “Classical Revival” 289

nur al-din, the qastal al-shu{aybiyya, and the “classical revival” 289 JULIAN RABY NUR AL-DIN, THE QASTAL AL-SHU{AYBIYYA, AND THE “CLASSICAL REVIVAL” Enter the medieval walled city of Aleppo by its principal we might dub the Revivalists and the Survivalists. gate on the west, the Bab Antakiyya, and you are almost Until a publication by Yasser Tabbaa in 1993, “clas- immediately confronted by the Qastal al-Shu{aybiyya. sical” in this context was often indiscriminately used to The present structure, which is of modest size, consists refer to two distinct architectural expressions in Syrian of little more than a facade comprising a sabºl-type foun- architecture: what we may briefly refer to as the Greco- tain and the vaulted entrance to a destroyed madrasa (figs. 1, 2).1 This facade is crowned by a disproportion- ately tall entablature that has made the Qastal a key monument in the debate over the “classical revival” in twelfth-century Syria. Michael Rogers featured the Qastal prominently in a major article published in 1971 in which he discussed numerous occurrences of the redeployment of classical buildings—and the less frequent copying of classical decoration—in Syria and Anatolia in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. I offer the following thoughts on the Qastal in admiration of just one aspect of Michael’s unparalleled erudition. Michael Rogers entitled his article “A Renaissance of Classical Antiquity in North Syria,” and argued that the “localisation of the classicising decoration…and its restriction to a period of little more than fifty years suggests very strongly that it was indeed a revival.”2 The suggestion I would like to propose here is that we need to distinguish more exactly between adoption and adaptation; that there are only very few structures with ex professo evocations of the classical past, and that the intention behind these evocations differed widely—in short, that we are not dealing with a single phenome- non, but with a variety of responses that call for more nuanced readings. -

Genealogy of the Concept of Securitization and Minority Rights

THE KURD INDUSTRY: UNDERSTANDING COSMOPOLITANISM IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY by ELÇIN HASKOLLAR A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School – Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Global Affairs written under the direction of Dr. Stephen Eric Bronner and approved by ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ Newark, New Jersey October 2014 © 2014 Elçin Haskollar ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Kurd Industry: Understanding Cosmopolitanism in the Twenty-First Century By ELÇIN HASKOLLAR Dissertation Director: Dr. Stephen Eric Bronner This dissertation is largely concerned with the tension between human rights principles and political realism. It examines the relationship between ethics, politics and power by discussing how Kurdish issues have been shaped by the political landscape of the twenty- first century. It opens up a dialogue on the contested meaning and shape of human rights, and enables a new avenue to think about foreign policy, ethically and politically. It bridges political theory with practice and reveals policy implications for the Middle East as a region. Using the approach of a qualitative, exploratory multiple-case study based on discourse analysis, several Kurdish issues are examined within the context of democratization, minority rights and the politics of exclusion. Data was collected through semi-structured interviews, archival research and participant observation. Data analysis was carried out based on the theoretical framework of critical theory and discourse analysis. Further, a discourse-interpretive paradigm underpins this research based on open coding. Such a method allows this study to combine individual narratives within their particular socio-political, economic and historical setting. -

The Hashemite Custodianship of Jerusalem's Islamic and Christian

THE HASHEMITE CUSTODIANSHIP OF JERUSALEM’S ISLAMIC AND CHRISTIAN HOLY SITES 1917–2020 CE White Paper The Royal Aal Al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought THE HASHEMITE CUSTODIANSHIP OF JERUSALEM’S ISLAMIC AND CHRISTIAN HOLY SITES 1917–2020 CE White Paper The Royal Aal Al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought THE HASHEMITE CUSTODIANSHIP OF JERUSALEM’S ISLAMIC AND CHRISTIAN HOLY SITES 1917–2020 CE Copyright © 2020 by The Royal Aal Al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought All rights reserved. No part of this document may be used or reproduced in any manner wthout the prior consent of the publisher. Cover Image: Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem © Shutterstock Title Page Image: Dome of the Rock and Jerusalem © Shutterstock isbn 978–9957–635–47–3 Printed in Jordan by The National Press Third print run CONTENTS ABSTRACT 5 INTRODUCTION: THE HASHEMITE CUSTODIANSHIP OF THE HOLY SITES IN JERUSALEM 7 PART ONE: THE ARAB, JEWISH, CHRISTIAN AND ISLAMIC HISTORY OF JERUSALEM IN BRIEF 9 PART TWO: THE CUSTODIANSHIP OF THE ISLAMIC HOLY SITES IN JERUSALEM 23 I. The Religious Significance of Jerusalem and its Holy Sites to Muslims 25 II. What is Meant by the ‘Islamic Holy Sites’ of Jerusalem? 30 III. The Significance of the Custodianship of Jerusalem’s Islamic Holy Sites 32 IV. The History of the Hashemite Custodianship of Jerusalem’s Islamic Holy Sites 33 V. The Functions of the Custodianship of Jerusalem’s Islamic Holy Sites 44 VI. Termination of the Islamic Custodianship 53 PART THREE: THE CUSTODIANSHIP OF THE CHRISTIAN HOLY SITES IN JERUSALEM 55 I. The Religious Significance of Jerusalem and its Holy Sites to Christians 57 II. -

Temple in Jerusalem Coordinates: 31.77765, 35.23547 from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Log in / create account article discussion edit this page history Temple in Jerusalem Coordinates: 31.77765, 35.23547 From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Bet HaMikdash ; "The Holy House"), refers to Part of a series of articles on ,שדקמה תיב :The Temple in Jerusalem or Holy Temple (Hebrew a series of structures located on the Temple Mount (Har HaBayit) in the old city of Jerusalem. Historically, two Jews and Judaism navigation temples were built at this location, and a future Temple features in Jewish eschatology. According to classical Main page Jewish belief, the Temple (or the Temple Mount) acts as the figurative "footstool" of God's presence (Heb. Contents "shechina") in the physical world. Featured content Current events The First Temple was built by King Solomon in seven years during the 10th century BCE, culminating in 960 [1] [2] Who is a Jew? ∙ Etymology ∙ Culture Random article BCE. It was the center of ancient Judaism. The Temple replaced the Tabernacle of Moses and the Tabernacles at Shiloh, Nov, and Givon as the central focus of Jewish faith. This First Temple was destroyed by Religion search the Babylonians in 587 BCE. Construction of a new temple was begun in 537 BCE; after a hiatus, work resumed Texts 520 BCE, with completion occurring in 516 BCE and dedication in 515. As described in the Book of Ezra, Ethnicities Go Search rebuilding of the Temple was authorized by Cyrus the Great and ratified by Darius the Great. Five centuries later, Population this Second Temple was renovated by Herod the Great in about 20 BCE. -

The Professorial Chair (Kursi ‘Ilmi Or Kursi Li-L-Wa‘Z Wa-L-Irshad) in Morocco La Cátedra (Kursi ‘Ilmi O Kursi Li-L-Wa‘Z Wa-L-Irsad) En Marruecos

Maqueta Alcantara_Maquetación 1 30/05/13 12:50 Página 89 AL-QANTARA XXXIV 1, enero-junio 2013 pp. 89-122 ISSN 0211-3589 doi: 10.3989/alqantara.2013.004 The Professorial Chair (kursi ‘ilmi or kursi li-l-wa‘z wa-l-irshad) in Morocco La cátedra (kursi ‘ilmi o kursi li-l-wa‘z wa-l-irsad) en Marruecos Nadia Erzini Stephen Vernoit Tangier, Morocco Las mezquitas congregacionales en Marruecos Moroccan congregational mosques are suelen tener un almimbar (púlpito) que se uti- equipped with a minbar (pulpit) which is used liza durante el sermón de los viernes. Muchas for the Friday sermon. Many mosques in Mo- mezquitas de Marruecos cuentan también con rocco are also equipped with one or more una o más sillas, diferenciadas del almimbar smaller chairs, which differ in their form and en su forma y su función ya que son utilizadas function from the minbar. These chairs are por los profesores para enseñar a los estudian- used by professors to give regular lectures to tes de la educación tradicional, y por eruditos students of traditional education, and by schol- que dan conferencias ocasionales al público ars to give occasional lectures to the general en general. Esta tradición de cátedras se intro- public. This tradition of the professorial chair duce probablemente en Marruecos desde Pró- was probably introduced to Morocco from the ximo Oriente en el siglo XIII. La mayoría de Middle East in the thirteenth century. Most of las cátedras existentes parecen datar de los si- the existing chairs in Morocco seem to date glos XIX y XX, manteniéndose hasta nuestros from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, días la fabricación y utilización de estas sillas. -

Sacred Architecture of the Rock : an Inno- Vative Design Concept and Iconography in Al-Aqsa Mosque

Milel ve Nihal, 14 (2), 2017 doi:10.17131/milel.377618 Sacred Architecture of the Rock : An Inno- vative Design Concept and Iconography in Al-Aqsa Mosque Haithem F. AL-RATROUT ∗ Citation/©: Al- Ratrout, Haithem (2017). Sacred Architecture of the Rock: An Innovative Design Concept and Iconography in Al-Aqsa Mosque, Milel ve Nihal, 14 (2), 49-73. Abstract: The religious sanctity and symbolisms of the Sacred Rock in Islam has been a frame of reference for inspiration of the architect who established a building over it in the early Islamic period. His challenging task was to generate an architectural archetype based on idea and concept in architec- ture vivid with sacredness and reflecting the religious symbolism of the place. Nowhere can this be true as Qubbet al-Sakhrah (the Dome of the Rock); an Islamic masterpiece which is considered to be the utmost achievement of the Umayyad Islamic religious art and architecture in the late seventh century C.E. It is evident that the architect of the Sacred Rock was very successful in dealing with the site when establishing an attracta- ble mature building that is dominating the skyline of the al-Aqsa mosque and the city of Islamicjerusalem alike. In addition to the Umayyad reli- gious objective in establishing this sacred building, another important goal was achieved which reinforced their political power and Islamic sover- eignty over the city. Indeed, Qubbet al-Sakhrah is a memorable building that commemorates the Sacred Rock and is full of religious feelings. It has, visually, strong impact on observers as its form and function recalls both of the archetype of Makkah and Islamicjerusalem and their religious experience. -

87 Review Article the FLORAL and GEOMETRICAL ELEMENTS ON

id10086515 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com Egyptian Journal of Archaeological and Restoration Studies "EJARS" An International peer-reviewed journal published bi-annually Volume 4, Issue 2, December - 2014: pp: 87-104 www. ejars.sohag-univ.edu.eg Review article THE FLORAL AND GEOMETRICAL ELEMENTS ON THE OTTOMAN ARCHITECTURE IN RHODES ISLAND Abdel Wadood M.1 & Panayotidi, M.2 1 Lecturer, Islamic Archeology dept., Faculty of Archaeology, Fayoum Univ., Fayoum, Egypt 2Professor, Archaeology and History of Art dept., Faculty of Philosophy, Athens Univ., Greece E-mail: [email protected] Received 27/8/2014 Accepted 13/10/2014 Abstract The Ottomans had inherited the decorative elements preceding them, and did not contend with such extent, but had developed and created at each of the Floral, geometric and writing adornments. The key features distinguishing Ottoman architecture in Rhodes (1523-1912AD) are the ornamental richness and the attention paid to the decorative side had been increasingly growing. Through what had reached us of the Ottoman period constructions, it would be apparent to us the tendency to decoration and that such decorative material had largely varied. Such ornaments had been represented in a number of types: * Floral ornaments * Geometrical ornaments. Keywords: Ottoman architecture, Ornamental elements, Floral ornaments, Geometrical ornaments, Rhodes. 1. Introduction Floral ornaments is meant by tried to bind between religion and plant ornaments every ornament relies in vegetable ornaments, as the some had its drawing or inscription on vegetable mentioned that the Moslem tendency to elements whether natural or altered from vegetable ornaments is a result of the nature in an image remote from its Koranic directives urging on avoiding the original one [1].