Drovers' Tracks and the Ancient Trails of the Middle Ground 1: the Drover's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

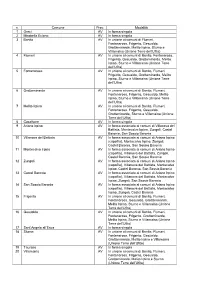

N. Comune Prov. Modalità 1 Greci AV in Forma Singola 2 Mirabella Eclano AV in Forma Singola 3 Bonito AV in Unione Ai Comuni Di

n. Comune Prov. Modalità 1 Greci AV In forma singola 2 Mirabella Eclano AV In forma singola 3 Bonito AV In unione ai comuni di Flumeri, Fontanarosa, Frigento, Gesualdo, Grottaminarda, Melito Irpino, Sturno e Villamaina (Unione Terre dell’Ufita) 4 Flumeri AV In unione ai comuni di Bonito, Fontanarosa, Frigento, Gesualdo, Grottaminarda, Melito Irpino, Sturno e Villamaina (Unione Terre dell’Ufita) 5 Fontanarosa AV In unione ai comuni di Bonito, Flumeri, Frigento, Gesualdo, Grottaminarda, Melito Irpino, Sturno e Villamaina (Unione Terre dell’Ufita) 6 Grottaminarda AV In unione ai comuni di Bonito, Flumeri, Fontanarosa, Frigento, Gesualdo, Melito Irpino, Sturno e Villamaina (Unione Terre dell’Ufita) 7 Melito Irpino AV In unione ai comuni di Bonito, Flumeri, Fontanarosa, Frigento, Gesualdo, Grottaminarda, Sturno e Villamaina (Unione Terre dell’Ufita) 8 Casalbore AV In forma singola 9 Ariano Irpino AV In forma associata ai comuni di Villanova del Battista, Montecalvo Irpino, Zungoli, Castel Baronia, San Sossio Baronia 10 Villanova del Battista AV In forma associata ai comuni di Ariano Irpino (capofila), Montecalvo Irpino, Zungoli, Castel Baronia, San Sossio Baronia 11 Montecalvo Irpino AV In forma associata ai comuni di Ariano Irpino (capofila), Villanova del Battista, Zungoli, Castel Baronia, San Sossio Baronia 12 Zungoli AV In forma associata ai comuni di Ariano Irpino (capofila), Villanova del Battista, Montecalvo Irpino, Castel Baronia, San Sossio Baronia 13 Castel Baronia AV In forma associata ai comuni di Ariano Irpino (capofila), Villanova -

Provvedimento N. 100 Del 26.10.2017

Di quanto sopra si è redatto il presente verbale che, previa lettura e conferma, viene sottoscritto come appresso: IL PRESIDENTE IL SEGRETARIO GENERALE Dott. Domenico Gambacorta Dr. Antonio Fraire =================================================================== Si dichiara che il presente provvedimento , è immediatamente eseguibile ai ORIGINALE sensi dell’art.134, comma 4, Tuel/ d.lgs. N. 267/2000. IL SEGRETARIO GENERALE Amministrazione Provinciale di Avellino Dr. Antonio Fraire Provvedimenti Presidenziali Avellino, lì ___________ ==================================================================== N. 100 del 26.10.2017 Si dichiara che il presente provvedimento è divenuto esecutivo ai sensi dell’art.134, comma 3, Tuel/ d.lgs. N. 267/2000 IL SEGRETARIO GENERALE Dr. Antonio Fraire OGGETTO: Approvazione progetto definitivo “LAVORI DI MANUTENZIONE Avellino, lì ___________ ORDINARIA DELLA SOVRASTRUTTURA DELLA RETE STRADALE DELLA PROVINCIA DI AVELLINO DELL'AMBITO ==================================================================== NORD ANNO 2017” della Provincia di Avellino. Il presente provvedimento è stato pubblicato all’Albo Pretorio on line della Provincia ai sensi dell’art. 32, della L.69 del 18.06.2009, giusta attestazione del Responsabile dal _____________ al ________________ IL SEGRETARIO GENERALE Dr. Antonio Fraire L’anno Duemiladiciassette il giorno VENTISEI del mese di OTTOBRE alle Avellino, lì ____________ ore 16,00 ad Ariano Irpino (AV), nella Casa Comunale il dott. Domenico GAMBACORTA, nominato Presidente della Provincia di Avellino a seguito dell’insediamento avvenuto in data 20 ottobre 2014, assistito dal Segretario Generale Dr. Antonio FRAIRE ha adottato il seguente Provvedimento Presidenziale Il DIRIGENTE DEL SETTORE LAVORI STRADALI - EDILIZIA SCOLASTICA E PATRIMONIO relaziona quanto segue: PREMESSO che Sulla presente proposta di deliberazione si Sulla presente proposta di deliberazione si • con Provvedimento Presidenziale n. 67 del 29/07/2017 è stato approvato il DUP con allegato il esprime, ai sensi degli artt.49, co.1 e n. -

Legenda Carta Della Pianificazione Regionale

(( (( (( (( (( (( (( (( (( (( (( ((((( ((((( (((( ( (((( ( ((((( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( (( ( ( (( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ((( ( ( ((( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( (( ( (( ( ( ( ((( (( ((( ( ( (( (( (( ( (( ((( (( ((( (( (( (( ( (( (( (( (( ( (( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( (((( ( (( ( ( (( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ((( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( (( (( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( (( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( ( (( ( ((( ( ( ( ((( ( (( ( ((( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( (( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( (( ( ( (( ( ( ( (( ( ( (( ( ( ( (( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ((( ( ( (((( ( ( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ((( ( ( ((( ( ( ((( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( ( -

Ordinanza Contingibile Ed Urgente Di Sospensione Temporanea Dell'attivita' Didattica in Presenza Delle Scuole Di Ogni

COMUNE DI SAN NICOLA BARONIA Provincia di AVELLINO Prot. 1966 del 19.04.2021 ORDINANZA N. 08/21 DEL 19.04.2021 OGGETTO: ORDINANZA CONTINGIBILE ED URGENTE DI SOSPENSIONE TEMPORANEA DELL’ATTIVITA’ DIDATTICA IN PRESENZA DELLE SCUOLE DI OGNI ORDINE E GRADO DEL COMUNE DI SAN NICOLA BARONIA – MISURA PRECAUZIONALE PER IL CONTENIMENTO DELLA DIFFUSIONE DEL “CORONAVIRUS” COVID 19. IL SINDACO VISTO il Decreto Legge del 23 febbraio 2020, n. 6 recente “Misure urgenti in materia di contenimento e gestione dell’emergenza epidemiologica da COVID-19”; VISTO il decreto legge 25 marzo 2020, n.19 recante “Misure urgenti per fronteggiare l’emergenza epidemiologica da Covid-19”, che ai sensi dell’articolo 2, comma 3 sono fatti salvi gli effetti prodotti e gli atti adottati sulla base dei decreti e delle ordinanze emanati ai sensi del decreto legge 23 febbraio 2020, n.6; VISTO il Decreto Legge del 16 maggio 2020, n. 33 “Ulteriori misure urgenti per fronteggiare l’emergenza epidemiologica da COVID-19”; VISTO il decreto-legge 30 luglio 2020, n. 83, convertito, con modificazioni, dalla legge 25 settembre 2020, n. 124, recante «Misure urgenti connesse con la scadenza della dichiarazione di emergenza epidemiologica da COVID-19 deliberata il 31 gennaio 2020»; VISTO il decreto-legge 14 gennaio 2021 n. 2. recante «Ulteriori disposizioni urgenti in materia di contenimento e prevenzione dell'emergenza epidemiologica da COVID- 19 e di svolgimento delle elezioni per l'anno 2021», con il quale lo stato di emergenza è stato prorogato fino al 30 aprile 2021; VISTO il decreto-legge 9 novembre 2020, n. 149, recante «Ulteriori misure urgenti in materia di tutela della salute, sostegno ai lavoratori e alle imprese e giustizia, connesse all'emergenza epidemiologica da COVID-19»; VISTO il decreto-legge 30 novembre 2020, n. -

Carta Dei Servizi Cure Domiciliari Integrate

REGIONE CAMPANIA Azienda Sanitaria Locale Avellino www.aslavellino.it Carta dei Servizi Cure Domiciliari Integrate DIRETTORE GENERALE DOTT.SSA MARIA MORGANTE 2018 A cura di: U.O.C. Assistenza Anziani V I A D E G L I I M B I M B O , 1 0 8 3 1 0 0 A V E L L I N O REGIONE CAMPANIA AZIENDA SANITARIA LOCALE AVELLINO www.aslavellino.it DIRETTORE GENERALE: DOTT.SSA MARIA MORGANTE DIRETTORE SANITARIO: DOTT.SSA EMILIA ANNA VOZZELLA DIRETTORE AMMINISTRATIVO: DOTT. FERDINANDO MEMOLI Edizione a cura: U.O.C. Assistenza Anziani Direttore: dott.ssa Anna Marro Collaboratori: · Dott. Cosimo A. Zarrella Dirigente Medico · Anna Maria Torello CPSS - Infermiera · Sergio Guerrera Coadiutore Amministrativo · Lidia Rinaldi CPSS Assistente Sanitaria Via Circumvallazione, 77 83100 Avellino Tel. 0825292649 e Fax 0825292650 e-mail: [email protected] IV Edizione Anno 2018 Tutti i diritti riservati 2 Indice Lettera di presentazione del servizio pag. 4 - 5 Il Territorio dell’ASL Avellino pag. 6 -7 Distretti, Comuni, Popolazione pag. 8 - 14 Chi siamo, cosa sono le cure domiciliari pag. 15 - 17 A chi sono rivolte, chi richiede il servizio pag. 18 - 19 Come si accede pag. 20 - 23 Dimissioni pag. 24 - 26 Dove operiamo pag. 27 – 36 Cosa vogliamo fare, come lo vogliamo pag. 37 - 39 Principi etici fondamentali pag. 40 – 42 Standard di Qualità pag. 43 - 50 Percorso Cure Domiciliari Integrate pag. 51 Appendice pag. 52 - 55 Legenda pag. 56 Ringraziamenti pag. 58 3 Lettera di presentazione del servizio Gent.le signora/e Il documento che sta per leggere, giunto alla quarta edizione, è la Carta del Servizio Cure Domiciliari Integrate dell’ASL Avellino, finalizzate all’assistenza di coloro che sono affetti da patologie cronico - degenerative e/o terminali. -

Comunità Montane Savignano Irpino

Provincia di Avellino Settore Pianificazione e Attività sul Territorio Servizio Protezione Civile Greci Montaguto Casalbore Comunità Montane Savignano Irpino Montecalvo Irpino Ariano Irpino Competenza territoriale Zungoli Villanova del Battista Melito Irpino Comunità Montana Ufita Bonito San Sossio Baronia Scampitella Flumeri Vallesaccarda Comunità Montana Alta Irpinia Grottaminarda Venticano San Nicola Baronia Pietradefusi Mirabella Eclano Chianche Castel Lacedonia Comunità Montana Partenio - Vallo di Lauro Montefusco Baronia Trevico Rotondi Roccabascerana Petruro Torrioni Torre le Vallata Irpino Nocelle Fontanarosa Sturno Tufo Carife Cervinara Santa Paolina Taurasi Monteverde Comunità Montana Irno - Solofrana San Martino Sant'Angelo all' Esca Altavilla Prata di Montemiletto Frigento Bisaccia Valle Irpina Gesualdo Aquilonia Caudina Pietrastornina Principato Grottolella Ultra Lapio Luogosano Comunità Montana Termino Cervialto Avella Pratola Serra Guardia Sant'Angelo a Scala Villamaina Rocca Lombardi Montefalcione San Sirignano Summonte Montefredane Paternopoli San Mango sul Calore Felice Quadrelle Capriglia Irpina Comuni non appartenenti Mugnano del Cardinale Ospedaletto Candida Torella dei Andretta Manocalzati Castelvetere sul Calore Sperone d'Alpinolo Parolise Lombardi Chiusano San Domenico Sant'Angelo Mercogliano Avellino San Potito Ultra dei Lombardi Morra de Baiano Castelfranci Calitri Atripalda Salza Irpina Sanctis Marzano Montemarano Sorbo Serpico di Nola Taurano Monteforte Cesinali Cairano Pago del Vallo di Lauro Irpino Santo -

Settore Viabilita' E Trasporti

Settore Viabilita' e Trasporti Determinazione N. 2105 del 28/10/2016 OGGETTO: FORNITURA E MONTAGGIO DI LAMA COPRI DENTI PER MACCHINA OPERATRICE SEMOVENTE TARGATA AJH 605 E COLTELLO LAMA TERRA PER UNIMOG TARGATO EB 022 TT – IMPEGNO SPESA ED AFFIDAMENTO; CIG N. ZBC1BA801B. IL DIRIGENTE DEL SETTORE PREMESSO che: l’art.· 14 – lettera A) del D. Lgs. n. 285 del 30/4/1992 stabilisce che gli Enti proprietari delle strade, allo scopo di garantire la sicurezza e la fluidità della circolazione, devono provvedere alla manutenzione, gestione e pulizia delle strade, delle loro pertinenze e arredo, nonché delle attrezzature, impianti e servizi; la· Provincia di Avellino gestisce tale servizio in gran parte con Personale dipendente utilizzando mezzi ed attrezzature di proprietà; per· assicurare il servizio descritto è necessario effettuare continua manutenzione sui suddetti automezzi ed attrezzature in modo da mantenerli sempre efficienti e sostituire i ricambi che si usurano periodicamente; tra· questi figurano una macchina operatrice semovente targata AJH 605 ed un Unimog targato EB 022 TT utilizzati dal personale dipendente per il servizio di pulizia strade, zanelle, cunette e svuotamento pozzetti; · è necessario provvedere all’acquisto di due lame di strisciamento da montare sui suddetti automezzi utilizzati come appena descritto dalle squadre di manutenzione in servizio presso i Centri operativi di Atripalda e Grottaminarda nonché le postazioni di Ponteromito e Bisaccia; è· stato richiesto per le vie brevi all’autofficina meccanica fabbro, “Lavorazioni in ferro MOSCHELLA GIOVANNI C/DA SABOLI, 9/10 83030 VILLANOVA DEL BATTISTA (AV)” part. IVA 02733980649”, inserita nell’elenco delle ditte di fiducia della Provincia di Avellino, la formulazione di un preventivo per la fornitura e montaggio delle suddette lame; La· suddetta autofficina ha fatto pervenire con nota prot. -

Dati Relativi Agli Impianti Gestiti Dalla Societa' Dati

DATI RELATIVI AGLI IMPIANTI GESTITI DALLA SOCIETA' DATI RELATIVI ALLE LOCALITA' SERVITE DAI SINGOLI IMPIANTI CODICE CODICE DITTA (*) DENOMINAZIONE IMPIANTO LOCALITA' CODICE ISTAT FASCIA CLIMATICA REMI 34749201 IT00CEY01127I Sparanise CE SPARANISE (CE) 61089 C 34756801 IT00BNO00046I San Lorenzello BN CERRETO SANNITA (BN) 62023 D 34768201 IT00AVO00051J Ariano Irpino AV ARIANO IRPINO (AV) 64005 E ATRIPALDA (AV) 64006 D 34768301 IT00AVO00012K Atripalda AV MANOCALZATI (AV) 64046 D AVELLA (AV) 64007 D BAIANO (AV) 64010 C MUGNANO DEL CARDINALE (AV) 64065 D 34768401 IT00AVO00070M Avella AV QUADRELLE (AV) 64076 D SIRIGNANO (AV) 64100 D SPERONE (AV) 64103 C AVELLINO (AV) 64008 D 34768500 IT00AVO00002J Avellino AV CESINALI (AV) 64026 D AIELLO DEL SABATO (AV) 64001 D 34769201 IT00AVO00073S Calitri AV CALITRI (AV) 64015 D 34769501 IT00AVO00067B Capriglia Irpina AV CAPRIGLIA IRPINA (AV) 64018 D CASALBORE (AV) 64020 D 34769701 IT00AVO00111E Casalbore AV BUONALBERGO (BN) 62011 D CHIANCHE (AV) 64027 D 34770401 IT00AVO00101D Chianche AV PETRURO IRPINO (AV) 64071 D TORRIONI (AV) 64111 E 34770701 IT00AVO00132L Conza della Campania AV CONZA DELLA CAMPANIA (AV) 64030 D 34770901 IT00AVO00129A Flumeri AV FLUMERI (AV) 64032 E 34771001 IT00AVO00068D Fontanarosa AV FONTANAROSA (AV) 64033 D 34771101 IT00AVO00103K Forino AV FORINO (AV) 64034 D GESUALDO (AV) 64036 E 34771301 IT00AVO00069F Gesualdo AV FRIGENTO (AV) 64035 E STURNO (AV) 64104 E 34771501 IT00AVO00040J Grottaminarda AV GROTTAMINARDA (AV) 64038 D 34771601 IT00AVO00104M Grottolella AV GROTTOLELLA (AV) 64039 -

Profilo Socio-Economico Boschi, Sorgenti E Geositi Della Baronia

QUADRO ECONOMICO E DEL CAPITALE SOCIALE IL PROFILO SOCIO ECONOMICO IN BARONIA Dopo un periodo piuttosto lungo in cui l’andamento dell’economia in Irpinia, compresa la Baronia, così come a livello nazionale, è stato piuttosto negativo, caratterizzato da crisi di competitività, stagnazione dei consumi, perdita di posti di lavoro e dalla percezione di un risveglio di fenomeni inflattivi, è diffusa la sensazione di entrare in una lenta ma tendenziale fase di ripresa: sensazione fondata sui primi dati di natura congiunturale e previsionale sul fronte dell’occupazione e soprattutto sulla convinzione che negli anni passati sia stato toccato il punto minimo del ciclo economico e che quindi, in prospettiva la situazione non potrà che migliorare. Di grande interesse per valutare lo stato di salute della nostra economia sono gli indicatori di natura creditizia, sia per capire le dinamiche in corso tra risparmio e consumi così importanti per il rilancio dell’economia in una fase di stagnazione, e sia per verificare in che misura il sistema bancario esercita le sue funzioni nell’ambito del nostro territorio: contribuire, cioè, in modo rilevante alla capacità di sviluppo del nostro sistema economico. Si auspica, pertanto, alla luce di un miglioramento dell’indicatore creditizio, solitamente utilizzato per dare un giudizio sintetico sul grado di solvibilità di una intera economia, che il sistema bancario possa dare un impulso più significativo all’intero sistema economico, per stimolare gli investimenti, a livello competitivo e quindi di conseguenza, anche ad incrementi della base occupazionale, innescando così un circolo virtuoso di sviluppo. Il quadro economico complessivo di una qualsiasi area geografica è ben sintetizzato dalle statistiche sul reddito prodotto. -

Sindaci Della Provincia

Prefettura di Avellino Ufficio Territoriale del Governo Elenco dei Sindaci della Provincia di Avellino ≈≈≈≈≈ COMUNE Cognome Nome Colore Politico AIELLO DEL SABATO URCIUOLI ERNESTO LISTA CIVICA ALTAVILLA IRPINA VANNI MARIO LISTA CIVICA ANDRETTA MIELE MICHELE LISTA CIVICA AQUILONIA DE VITO GIANCARLO LISTA CIVICA ARIANO IRPINO FRANZA ENRICO LISTA CIVICA ATRIPALDA SPAGNUOLO GIUSEPPE LISTA CIVICA AVELLA BIANCARDI DOMENICO LISTA CIVICA AVELLINO FESTA GIANLUCA LISTA CIVICA COMMISSARIO BAGNOLI IRPINO STRAORDINAZIO BAIANO MONTANARO ENRICO LISTA CIVICA BISACCIA ARMINIO MARCELLO ANTONIO LISTA CIVICA BONITO DE PASQUALE GIUSEPPE LISTA CIVICA CAIRANO D’ANGELIS LUIGI LISTA CIVICA CALABRITTO CENTANNI GELSOMINO LISTA CIVICA CALITRI DI MAIO MICHELE LISTA CIVICA CANDIDA PICONE FAUSTO LISTA CIVICA CAPOSELE MELILLO LORENZO LISTA CIVICA CAPRIGLIA IRPINA PICARIELLO NUNZIANTE LISTA CIVICA CARIFE MANZI ANTONIO LISTA CIVICA CASALBORE FABIANO RAFFAELE LISTA CIVICA CASSANO IRPINO VECCHIA SALVATORE LISTA CIVICA CASTEL BARONIA MARTONE FELICE LISTA CIVICA CASTELFRANCI CRESTA GENEROSO LISTA CIVICA CASTELVETERE SUL CALORE MOCCIA GENEROSO LISTA CIVICA CERVINARA LENGUA CATERINA LISTA CIVICA CESINALI FIORE DARIO LISTA CIVICA CHIANCHE GRILLO CARLO LISTA CIVICA CHIUSANO DI SAN DOMENICO DE ANGELIS CARMINE LISTA CIVICA CONTRADA DE SANTIS PASQUALE LISTA CIVICA CONZA DELLA CAMPANIA CICCONE LUIGI LISTA CIVICA DOMICELLA CORBISIERO ANTONIO LISTA CIVICA FLUMERI LANZA ANGELO ANTONIO LISTA CIVICA FONTANAROSA PESCATORE GIUSEPPE LISTA CIVICA COMMISSARIO FORINO STRAORDINARIO FRIGENTO -

N. Comune Prov. Modalità Data Di Trasferimento Delle Funzioni 1

Data di trasferimento n. Comune Prov. Modalità delle funzioni 1 Ariano Irpino AV In forma associata ai comuni di Villanova del Battista, 24/07/2012 Montecalvo Irpino, Zungoli, Castel Baronia, San Sossio Baronia 2 Bonito AV In unione ai comuni di Flumeri, Fontanarosa, 24/07/2012 Frigento, Gesualdo, Grottaminarda, Melito Irpino, Sturno e Villamaina (Unione Terre dell’Ufita) 3 Casalbore AV In forma singola 24/07/2012 4 Castel Baronia AV In forma associata ai comuni di Ariano Irpino 24/07/2012 (capofila), Villanova del Battista, Montecalvo Irpino, Zungoli, San Sossio Baronia 5 Flumeri AV In unione ai comuni di Bonito, Fontanarosa, Frigento, 24/07/2012 Gesualdo, Grottaminarda, Melito Irpino, Sturno e Villamaina (Unione Terre dell’Ufita) 6 Fontanarosa AV In unione ai comuni di Bonito, Flumeri, Frigento, 24/07/2012 Gesualdo, Grottaminarda, Melito Irpino, Sturno e Villamaina (Unione Terre dell’Ufita) 7 Greci AV In forma singola 24/07/2012 8 Grottaminarda AV In unione ai comuni di Bonito, Flumeri, Fontanarosa, 24/07/2012 Frigento, Gesualdo, Melito Irpino, Sturno e Villamaina (Unione Terre dell’Ufita) 9 Melito Irpino AV In unione ai comuni di Bonito, Flumeri, Fontanarosa, 24/07/2012 Frigento, Gesualdo, Grottaminarda, Sturno e Villamaina (Unione Terre dell’Ufita) 10 Mirabella Eclano AV In forma singola 24/07/2012 11 Montecalvo Irpino AV In forma associata ai comuni di Ariano Irpino 24/07/2012 (capofila), Villanova del Battista, Zungoli, Castel Baronia, San Sossio Baronia 12 San Sossio Baronia AV In forma associata ai comuni di Ariano Irpino 24/07/2012 (capofila), Villanova del Battista, Montecalvo Irpino, Zungoli, Castel Baronia 13 Savignano Irpino AV In forma singola 19/06/2013 14 Villanova del Battista AV In forma associata ai comuni di Ariano Irpino 24/07/2012 (capofila), Montecalvo Irpino, Zungoli, Castel Baronia, San Sossio Baronia 15 Zungoli AV In forma associata ai comuni di Ariano Irpino 24/07/2012 (capofila), Villanova del Battista, Montecalvo Irpino, Castel Baronia, San Sossio Baronia . -

Ÿþm I C R O S O F T W O R

CURRICULUMFORMATIVO EPROFESSIONALE AVV. RAFFAELE PANZETTA Dichiarazione resa ai sensi degli artt. 46 e 47 del DPR 445/2000 DATIPERSONALI Data e luogo di nascita: Villanova del Battista il 05/05/1956 Nazionalità:Italiana Stato civile:Coniugato Residenza: Villanova del Battista – Via Circumvallazione n. 9 - Servizio militare: Assolto mediante servizio effettivo - Patente di Guida: C-E. Tel.0825-826015 Cod. Fisc.: PNZ RFL 56E05 L973L ISTRUZIONEEFORMAZIONEPROFESSIONALE Diploma Geometra Istituto “G.Bruno” Ariano Irpino (AV) Laurea in Giurisprudenza presso l’Università degli Studi di Salerno - Esame di stato per abilitazione all’esercizio della professione di Geometra – Abilitazione all’esercizio della professione di Avvocato. STAGESECONVEGNI Scuola Superiore di Amm.ne per Enti Locali - Roma a) Condono Edilizio Legge n. 47/85 b) Riforma della Pubblica Amministrazione – Leggi Bassanini . Lega delle autonomie Locali – a) Legge sugli appalti pubblici – L. 109/94 – Consorzio dei Comune – Asmez Napoli - a) Giornata di Studio sullo S.U.A.P. Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri – Regione Campania – Asmez. a) Corso di Formazione di 120 ore ed esame finale su S.U.A.P. Comune di Ariano Irpino – Casa Editrice IPSOA – a) Giornata di Studio su Projet financing. Amsez Campania – Napoli a) I procedimenti disciplinari pubblico impiego. ESPERIENZEPROFESSIONALI Responsabile Ufficio Legale – Personale presso Comune di Villanova del Battista – Responsabile - Contenzioso Tributario e SUAP presso Comune di Villanova del Battista Componente Commissione Provinciale ex art. 11 bis del D.L. 384/92 – Componente Commissione per l’assegnazione dei suoli nel P.I.P. del Comune di Montaguto ( AV); Componente della Commissione ex art. 14 della Legge 219/81 – Comune di Zungoli.