Review Reviewed Work(S): Fi Rassi / Dans Ma Tête Un Rond-Point

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entire Issue (PDF)

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 114 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 162 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 4, 2016 No. 21 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was last day’s proceedings and announces Red, White, and Blue’s great work in called to order by the Speaker pro tem- to the House his approval thereof. enriching the lives of veterans in need. pore (Mr. MOONEY of West Virginia). Pursuant to clause 1, rule I, the Jour- I had the great privilege of knowing f nal stands approved. Ted personally and was inspired by his kindness, his humor, and his love for DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER f his family and country. Ted will al- PRO TEMPORE PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE ways be remembered as an honorable The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- The SPEAKER pro tempore. Will the young man who touched many lives, fore the House the following commu- gentlewoman from New York (Ms. having a lasting positive impact on all nication from the Speaker: STEFANIK) come forward and lead the who knew and loved him. WASHINGTON, DC, House in the Pledge of Allegiance. May his name forever be remembered February 4, 2016. Ms. STEFANIK led the Pledge of Al- in the CONGRESSIONAL RECORD and in I hereby appoint the Honorable ALEXANDER legiance as follows: the great United States of America. X. MOONEY to act as Speaker pro tempore on this day. I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America, and to the Repub- f PAUL D. -

RESPONDING to CHALLENGES in MEDICAL DEVICE SECURITY? Tara Larson

RESPONDING TO CHALLENGES IN MEDICAL DEVICE SECURITY? Tara Larson - Chief Security Architect CRHF Medtronic 10-May- 2015 HOMELAND SEASON 2, EPISODE 10 – “BROKEN HEARTS” HYPOTHESIZED PACEMAKER HACK Challenge: Hypothesized “hack”: . Bad guy breaks into the Vice President’s home . Finds VP’s remote monitor . Provides the home monitor serial number to a remote hacker . Hacker remotely and wirelessly adjusts a pacemaker setting using monitor serial number . VP is killed instantly from ventricular fibrillation Let’s talk about reality and then get back to this one. 2016 MEDEC Regulatory Conference DESIGN FOR SECURITY CHALLENGES . Agenda: . What is the problem? . How do we solve the challenge? . Design for Security . How is medical device security different for IT security? . How are Medical Device Manufacturers Assessing product risk? . How do Medical Device Manufacturers ensure security for product lifecycle? 2016 MEDEC Regulatory Conference MEDICAL DEVICE SECURITY PROBLEMS .Protection of therapy systems and services including data from unauthorized modification, destruction or disclosure that can lead to patient harm or loss of customer trust. Protection controls often only present the opportunity to secure at time of manufacturing. Often the device must live inside a human body for the life of the battery. 2016 MEDEC Regulatory Conference CHALLENGES IN MEDICAL DEVICE SECURITY . Security engineering principles . IT Security practices are hard to apply to Medical Devices . Product Security risk assessment . Must be tied to safety and include business risks . Generating actionable & testable cybersecurity requirements . Security Requirements are not positive , hard to test a negative . Understanding Threat Models . Threat models must encompass Common Vulnerability and Product threats . Security risk mitigations from industry applied to medical devices . -

Arizona Human Trafficking Council June 2, 2021, 9:00 AM Virtual

Arizona Human Trafficking Council June 2, 2021, 9:00 AM Virtual Meeting 1700 West Washington Street, PHOENIX, ARIZONA 85007 A general meeting of the Arizona Human Trafficking Council was convened on June 2, 2021 virtually, 1700 West Washington Street, Phoenix, Arizona 85007, notice having been duly given. Members Present (21) Members Absent (5) Cindy McCain, Co-Chair David Curry Maria Cristina Fuentes, Co-Chair Marsha Calhoun Brian Steele Rachel Mitchell Cara Christ Lois Lucas Debbie Johnson Nathaniel Brown Dominique Roe-Sepowitz Doug Coleman Tony Mapp (Proxy for Heston Silbert) Jennifer Crawford Jill Rable Dave Saflar (Proxy for James Gallagher) Jim Waring Joseph Kelroy Jeramia Ramadan (Proxy for Michael Wisehart) Mike Faust Sarah Beaumont Sarah Kent Sheila Polk Tim Roemer Zora Manjencich Heather Carter Staff and Guests Present (9) Kim Brooks Nick Lien Vianney Careaga Nick Alamshaw Claire Merkel Mike Russo Joanna Jauregui Anastasia Stinchfield Julia Martin Arizona Human Trafficking Council 06/02/2021 Meeting Minutes Page 2 of 7 Call to Order ● Mrs. Cindy McCain, Co-Chair, called the Arizona Human Trafficking Council meeting to order at 9:01 a.m. with 21 members and 9 staff and guests present. Roll Call ● Director Maria Cristina Fuentes, Co-Chair, welcomed Director Tim Roemer, Arizona Department of Homeland Security, as the newest member of the Council. Prior to this change in leadership, Director Roemer served as Arizona’s Chief Information Security Officer. With his appointment to Homeland Security, the cyber security operations overseen by Director Roemer at Arizona Department of Administration has shifted to Homeland Security, allowing the state to better protect citizens from cybersecurity attacks. -

God Overcomes Our Broken Hearts | Outrageous #4

God Overcomes Our Broken Hearts | Outrageous #4 www.pursuegod.org /god-overcomes-our-broken-hearts-outrageous-4/ Heartbreak Is an Inescapable Part of Life The Bible provides many examples of the heartaches common in life. For example, Hannah was heartbroken because of infertility. 1 Samuel 1:10 “Hannah was in deep anguish, crying bitterly as she prayed to the Lord.” King David experienced heartbreak over the death of his son. 2 Samuel 18:33 The king was overcome with emotion. He went up to the room over the gateway and burst into tears. And as he went, he cried, ‘O my son Absalom! My son, my son Absalom! If only I had died instead of you! O Absalom, my son, my son.” The prophet Jeremiah lived through the destruction of his homeland by invasion. Lamentations 2:11 I have cried until the tears no longer come; my heart is broken. My spirit is poured out in agony as I see the desperate plight of my people. Even Jesus was not exempt from heartbreak. Isaiah 53:3 He was despised and rejected – a man of sorrows, acquainted with deepest grief. God Will Restore All Our Losses God will turn our fortunes around – but it might not happen the way you expect. For example, it may or may not happen in this life. God eventually gave Hannah a son. But David and Jeremiah lived with their losses for the rest of their lives. But if not in this life, God’s restoration will happen in the life to come. One day all things will be made new. -

2019 Music Church

2019 music for the church GIA PUBLICATIONS, INC. giamusic.com/ritualsong RITUAL SONG —SECOND EDITION giamusic.com/ritualsong A BALANCED MIX OF MUSICAL STYLES FROM CHANT TO CONTEMPORARY AND EVERYTHING IN BETWEEN Recordings Children’s Book pages 8 Wedding Resource page 9 pages 8 BLEST NEW are those WHO LOVE MUSIC FOR THE 2019 WEDDING LITURGY Hymnody Liturgical Collections pages 12 & 13 pages 6 & 7 Masses page 11 KNOWN UNK NOW NS O UR H EARTS A RE R ESTLESS Deep and Lasting Peace Michael Joncas 100 CONTEMPORARY TEXTS VOLUME 2 TO COMMON TUNES MASS of JOHN L. BELL & GRAHAM MAULE L I F E the LAMB I S John L. Bell • David Bjorlin • Mary Louise Bringle • Ben Brody CHANGED, Rory Cooney • Ruth Duck • Delores Dufner, OSB • David Gambrell Francis Patrick O’Brien Michael Joncas • Jacque Jones • Sally Ann Morris • Adam Tice New Instrumental Music E PHREM F EELEY GIA PUBLICATIONS, INC. page 10 & 13 N O T ENDED GIA PUBLICATIONS, INC. Volume 3 PAUL TATE Gathered to Worship Organ Music based on Hymn Tunes Prayer Resources GIA PUBLICATIONS, INC. Arranged by Mary Beth Bennett pages 6 & 7 Edwin T. Childs J. William Greene Raymond H. Haan Benjamin Kolodziej David Lasky Harold Owen Books for the Pastoral Musician Nicholas Palmer Robert J. Powell Bernard Wayne Sanders pages 9 & 10 HYMNS, PSALMS & PRAYERS TO END THE DAY Sing as Christ Inspires Your ong s Touchstones for Pastoral Musicians EVOKING SOUND GIA PUBLICATIONS, INC. DaviD haas The Complete Choral Warm-Up Sequences New Hymnal & Worship A COMPANION TO THE CHORAL WARM-UP CANTOS PARA Resource page 12 James Jordan EL PUEBLO DE DIOS Jesse Borower ONE LORD, ONE FAITH, ONE BAPTISM SONGS FOR THE PEOPLE OF GOD Skill Building Resources page 14 WELCOME We’ve been busier than ever developing new resources effort (page 12) . -

Showtime Unlimited Schedule December 1, 2012 12:00 AM 12:30 AM 1:00 AM 1:30 AM 2:00 AM 2:30 AM 3:00 AM 3:30 AM 4:00 AM 4:30 AM 5:00 AM 5:30 AM

Showtime Unlimited Schedule December 1, 2012 12:00 AM 12:30 AM 1:00 AM 1:30 AM 2:00 AM 2:30 AM 3:00 AM 3:30 AM 4:00 AM 4:30 AM 5:00 AM 5:30 AM SHOWTIME Jim Rome On Showtime: 102 TVPG Inside The NFL: 2012 Week 12 TVPG Dave's Old... TVMA Shaquille O'Neal Presents: All Star Reservoir Dogs (3:45) R ALL ACCESS:... Comedy Jam - Live from Orlando TVMA (5:25) TV14 SHO 2 Next Stop Bruno R Red State R Joan Rivers: Don't Start With Me TVMA Loosies (4:45) PG13 for... TVMA SHOWTIME 50/50 R The Burning Plain (12:40) R Alien Raiders R Limelight (2011) TVMA SHOWCASE SHO EXTREME ALL ACCESS:... Goon R Paper Soldiers (2:05) R Tactical Force (3:35) R Believers (5:05) R TV14 SHO BEYOND Terror Trap R Blood Creek R Evil Eyes R Time Bandits PG SHO NEXT Blubberella R Blitz R The Company Men (2:10) R The Bang Bang Club R SHO WOMEN Ceremony R The Constant Gardener R Addicted to Her Love (2:45) R Fatal Error TV14 SHOWTIME Cutthroat Island (11:40) PG13 Comeback Season (1:45) PG13 Country Remedy (3:25) PG Alanand... (5:10) PG FAMILY ZONE THE MOVIE Hobo With a... Ghost Machine (12:35) R Play Dead (2:15) TVMA The Rich Man's Wife (3:45) R Other Woman,... R CHANNEL (11:05) TVMA THE MOVIE Psychosis (11:35) R Isolation (1:10) R Psychosis (2:45) R The Deal (4:35) R CHANNEL XTRA FLiX Chasing Amy R Steal R 50 Pills TVMA 3 A.M. -

Book Group to Go Book Group Kit Collection Glendale Library, Arts & Culture

Book Group To Go Book Group Kit Collection Glendale Library, Arts & Culture Full Descriptions of Titles in the Collection —Fall 2020 Book Group Kits can be checked out for 8 weeks and cannot be placed on hold or renewed. To reserve a kit, please contact: [email protected] or call 818-548-2021 101 Great American Poems edited by The American Poetry & Literacy Project Focusing on popular verse from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, this treasury of great American poems offers a taste of the nation's rich poetic legacy. Selected for both popularity and literary quality, the compilation includes Robert Frost's "Stopping by the Woods on a Snowy Evening," Walt Whitman's "I Hear America Singing," and Ralph Waldo Emerson's "Concord Hymn," as well as poems by Langston Hughes, Emily Dickinson, T. S. Eliot, Marianne Moore, and many other notables. Poetry. 80 pages The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie In his first book for young adults, bestselling author Sherman Alexie tells the story of Junior, a budding cartoonist growing up on the Spokane Indian Reservation. Determined to take his future into his own hands, Junior leaves his troubled school on the rez to attend an all-white farm town high school where the only other Indian is the school mascot. Heartbreaking, funny, and beautifully written, the book chronicles the contemporary adolescence of one Native American boy. Poignant drawings by acclaimed artist Ellen Forney reflect Junior’s art. 2007 National Book Award winner. Fiction. Young Adult. 229 pages The Age of Dreaming by Nina Revoyr Jun Nakayama was a silent film star in the early days of Hollywood, but by 1964, he is living in complete obscurity— until a young writer, Nick Bellinger, reveals that he has written a screenplay with Nakayama in mind. -

Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Commission

MARJORY STONEMAN DOUGLAS HIGH SCHOOL PUBLIC SAFETY COMMISSION PublicMSD Safety Commission Initial Report Submitted to the Governor, Speaker of the House of Representatives and Senate President January 2, 2019 In memory of: Alyssa Alhadeff Scott Beigel Martin Duque Nicholas Dworet Aaron Feis Jaime Guttenberg Chris Hixon Luke Hoyer Cara Loughran Gina Montalto Joaquin Oliver Alaina Petty Meadow Pollack Helena Ramsay Alex Schachter Carmen Schentrup Peter Wang But for a Small Moment Tragedy falls, and takes what cannot be replaced: Time, moments, milestones, Togetherness. Darkest clouds of trouble, a peace destroyed. Suddenly, senselessly, Publicly. Yet night briefly yields, and rays of love uncommon shine. Broken hearts together, United. Not to supplant, but to illuminate a journey blessed by grace. Deeply etched, always Remembered. Our truest promise, vitally renewed in her: To live and love and strive. Until joyfully reunited, a family Forever. Written for Alaina Petty by anonymous. Dedicated to each of the 17 families. It was only a week prior to February 14, 2018 that our daughter, Alyssa Alhadeff, had selected her course load for the upcoming academic Sophomore year. Honors English, Pre-Calc, Chemistry and Spanish 4 topped her list...had such a bright future ahead of her! Hard to imagine, though, that I now must write about our beautiful 14 year old in the past tense. Not only an academic talent, Alyssa shone brightly athletically as well. Having begun to play soccer at the age of 3, she held the position as attacking mid-fielder wearing the number 8 with pride. Her unbelievable passing skills, coupled with her ability to communicate as a leader on the field, were paving her way to athletic prowess. -

Bridges Summer 2021 Bridges Summer 2021 6/14/21 11:11 AM Page 1

Bridges Summer 2021_Bridges Summer 2021 6/14/21 11:11 AM Page 1 Brethren Disaster Ministries Rebuilding Homes • Nurturing Children • Responding Globally Vol. 22, Summer 2021 Pondering Connections— INSIDE Hurricanes, Tornados, Migrating COVID-19 Response Updates............2 CDS Updates ....................................3 Children, and NE Nigeria Who is my neighbor? ........................3 by Roy Winter Rebuilding Lives in Central While pondering the America: Hurricane Recovery ..........4 diversity of BDM’s CDS Moving Forward with Fall different ministries in Training Schedule............................4 this issue, I was struck Grants Expand Nigeria Crisis by how they have an Response and COVID-19 Relief ......5 important connection. Volcanic Eruption near Goma, Maybe thinking about DR Congo ......................................5 these connections can Rebuilding Updates ..........................6 help us be better partners Would you like to receive BRIDGES in disaster recovery and by email?..........................................6 even work more at BDM Project Expenses Correction ....6 preventing future disasters. A New Pathway for Renters in Dayton, Ohio ..................................7 Having two major Aerial view of some of the flooding caused by Hurricane Eta in Honduras. hurricanes strike land in Photo courtesy of U.S. Navy Rebuilding Homes and Mending Broken Hearts ................................7 November (Eta & Iota in Central America) caused me to really tornados, and floods. I understand that Virtual Blood Drive -

In Lebanon» Project and Funded by Germany Through the German Development Bank (Kfw)

The Beirut Explosion: Healing the Wounds This supplement is produced by the UNDP «Peace Building in Lebanon» project and funded by Germany through the German Development Bank (KfW). The Arabic version is distributed with An- Nahar newspaper while the English version is distributed with The in Lebanon Daily Star and the French version with L’Orient-Le Jour. The supplement contains articles by writers, journalists, media professionals, researchers and artists residing in Lebanon. They cover issues related to civil peace in addition to the repercussions of the News Supplement Syrian crisis on Lebanon and the relations between Lebanese and Syrians, employing objective approaches that are free of hatred and Issue nº 25, September 2020, "Beirut Explosion: Healing the Wounds" misconceptions. Artwork by Lamis Nashef by Artwork © 03 Beirut Explosion: How did the State Manage the Disaster 08 Volunteer Testimonials The International Community and the Beirut Explosion: The Required, the Expected 04 and the Possible 05 Like Our Parents Before Us: New Generation Battles Beirut Blast Trauma 05 COVID-19 and the Blast: A Response Amidst Multiple Crises Family and Community Support for Child and Adolescent Mental Health in the 06 Aftermath of the Beirut Port Explosion 07 Beirut’s Tragedy: Reviving a Lost Sense of the Lebanese National Belonging 10 Beirut Loves its Refugees 10 A Piece of Home that Never Leaves: The Lebanese Diaspora's Role in Rebuilding Beirut 11 Contemplating a Green Reconstruction of Beirut 12 Protecting the Tenants: A Core Issue in Recovering a Viable City 13 Heritage Recovery In Context: Beirut, Post-Blast 14 Simple Tools that Enable Anyone to Uncover Fabricated Information Beirut Explosion: The Agonizing Wait of Families in Search of Missing 15 Loved Ones – Increased Difficulties Due to Poor Coordination The in Lebanon Issue nº 25, September 2020, "Beirut Explosion: Healing the Wounds" 2 news supplement Building Lebanon All Hands on Deck to Support Beirut Forward Mr. -

April 17Th 2021

Published Bi-Weekly for the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska • Volume 50, Number 8 • Saturday, April 17, 2021 Bago Bits… Winnebago Land Transfer Act is Introduced into Congress Congratulations to Winnebago’s back-to- back wrestling champion Zeriah George on another amazing accomplishment over the weekend of April 3rd. Zeriah was named GOLD ALL-AMERICAN and went 8-0 at the AAU National Duals in Des Moines, IA. H.R.2402 - 117th Congress (2021-2022): To transfer administrative jurisdiction of certain Federal lands from the Army Corps of Engineers to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, to take such lands into trust for the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska, and for other purposes. | Congress.gov | Library of Congress Fortenberry Introduces Win- Feenstra (IA-04) “I am glad to be United States District Court for nebago Land Transfer Act working with Reps. Fortenberry, the Northern District of Iowa On Apr 8, 2021,Washington, Davids, and Soto on this impor- Western Division and the United DC--Congressman Jeff Forten- tant legislation. This is another States District Court for the Dis- berry (NE-01) made the following example of government overreach trict of Nebraska. On the Tribe’s statement today upon his intro- that needs to be addressed, and appeal of the Nebraska case, the On behalf of the Winnebago Tribe, duction of the Winnebago Land our bipartisan effort is a step in United States Court of Appeals congratulations to our Winnebago Public Transfer Act. the right direction.” for the Eighth Circuit found that Health Department’s Medical Services “Several decades ago, land STATEMENT REGARDING THE the Corps illegally condemned Program and Public Health Nursing belonging to the Winnebago tribe WINNEBAGO LAND TRANSFER the land and that the land could Department for being recognized in the ACT only be taken by an act of Con- Great Plains Area 2020 Awards! of Nebraska was appropriated by the Arms Corps of Engineers for Winnebago, NE - The Winneba- gress but because the Tribe development. -

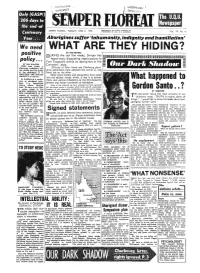

What Are They Hiding?

^UEENcuiVD ^ UNIVERSITY. Hiiii 'l§il§gend^ IMHIi Registered at the O.P.O., BrL-ibanfl. for SEMPER FLOREAT, TUESDAY, JUNE 9, 1959. transmission by post as a periodical. VOL, 29, No. 6 Aborigines suffer 'inhumanity^ indignity and liumiliation' IVe need WHAT ARE THEY HIDING? BY THE EDITORS positive TOURING the last few weeks, Semper has heard many disquieting repercussions to policy • • • Tom Toogood's article on aboriginals in the BY IAN WALTON Commem. issue. THIS Issue quotes a ihir JOarh ShuMm Cherbourg settlement offl Officials of Palm Island and Cherbourg abori cial statin; that the policy ginal settlements have attacked the article on one iiiiirriiiniiiriniiimiifniiiimu iiiiiiDiiiiiuiiitii :uiiiuuiimiiimHi»imiijnnijMuii»iiJjmwjjijiinfiiiiiiijHiiJ'Uuiuuii»iinHnjiiiijjiiiijfiJun<iiji»inijMMiijiiWJjuiJJuiirmtM,unuid of the settlement is to hand, but on the other ... .MAINTAIN THE RACIAL IDENTITY of natives. Many grave claims and accusations have come into the editors' hands, which, if one is to believe At Armidale at a confer What happened to ence on aboriginal prob them, cast serious reflections on the Government's lems, the Queensland present and future treatment of aborigines. Native Affairs Director Some of the material we have received has been ignored; said, "We have in our State but we cannot ignore a situation which finds several responsible a policy aimed at the members of the community confronting us with similar allega Gordon Santo..? QUICK DISPOSAL INTO tions about the privations of our aboriginals: indrgnify, inhuman BY INQUIRER THE COMMUNITY of all ity, humiliation. HE inscription above the main entrance to our capable of accepting the A Semper representative tried to check the truth of these responsibility, and of help allegations with the Government Department.