A New Deal for Journalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Journal of Textile Science and Engineering Chowdhary U

International Journal of Textile Science and Engineering Chowdhary U. Int J Text Sci Eng 3: 125. Review Article DOI: 10.29011/IJTSE-125/100025 Impact of Interfacings and Lining on Breaking Strength, Elongation and Duration of the Test for Knitted Wool Usha Chowdhary* Department of Human Environmental Studies Fashion Merchandising and Design, Central Michigan University, Mount Pleasant, Mich- igan, USA *Corresponding author: Usha Chowdhary, Department of Human Environmental Studies Fashion Merchandising and Design, Central Michigan University, Mount Pleasant, Michigan, USA. Email: [email protected] Citation: Chowdhary U (2019) Impact of Interfacings and Lining on Breaking Strength, Elongation and Duration of the Test for Knitted Wool. Int J Text Sci Eng 3: 125. DOI: 10.29011/IJTSE-125/100025 Received Date: March 5, 2019; Accepted Date: March 20, 2019; Published Date: March 29, 2019 Abstract The study examined breaking strength, elongation and time at break for 100% medium weight knitted wool with in- terfacings and lining. Several ASTM standards were used to measure structural and performance attributes. Fabric strength, elongation, and time taken to rupture for fabric exclusively and with interfacings and lining attached were measured for eight relationships. Hypotheses were tested using T-test analysis. Confidence level was established at 95%. Results revealed that majority of the hypotheses were accepted. Results for fusible and non-fusible interfacings varied. Adding fusible interfacing did not enhance strength in the lengthwise direction. Fusible and non-fusible interfacings did not differ for elongation. It took longer for fabric to break in lengthwise than the crosswise direction. Future research is needed to confirm the findings of this study for various fabrics, seam types, stitch types, fabric construction and fiber contents. -

RK-Praise-1.Pdf

Praise Music has always been a big part of my life. As a child, I loved to sing. When I was 12, I was so excited to receive a stereo for my birthday. At 16, I discovered the joy of driving my car and listening to music that matched my mood. As an adult, I have learned to love all types of music: hymns, contemporary praise, show tunes, and top 40, to name a few. Music frequently is playing in the background at my house and in my offce. I think my love of music is connected to how it speaks to us. It can help us express thoughts and emotions when words do not seem to work. It can make us laugh and energize us, and it can remind us of important truths about our relationship with Jesus Christ. Many songs reinforce the Good News we encounter in scripture. They sometimes spark within us a new understanding of our identity in Christ. Music connects to people of all ages and brings us together. These things inspired us to create devotions centered around song and scripture. Over the next few weeks, we will listen to contemporary Christian music, hymns, and songs from Roswell Kids. We will explore their connections to scripture and dive deeper into how they can help shape and form our faith. We hope these devotions will help your family create space in your days to focus on God, to refect on how God is speaking, and to engage in activities that help reinforce the messages. Please know you are in our prayers and that we miss your families. -

2016 Program Angv5.Pdf

��������� ������������������� ��������������������� ������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ��������������������������������������� Table of contents ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������ 3 Table of contents Table of contents 4 5 Table of contents Table of contents 6 7 Table of contents Table of contents 8 9 Conference rooms location 1 0 Pijalnia Building A �� �������� �������� ���������������� ������������ �������������������� �������������� ��������������������������� �������� ������������������������� ��������� ���������������������������� ������������� ������� �������� �� ����������� �������� �������� �������� ������������������������� ������������ ����������������� ��������� �������� �������� ����������������������� ��������������� �������� �������� �������� �������� ���������������� ������������ �������������������� �������������� ��������������������������� ������������ ������� ������� ����� ����� ��������� Building����������� B ������������ Nowy Dom Zdrojowy �������������������������� ������������� ������� -

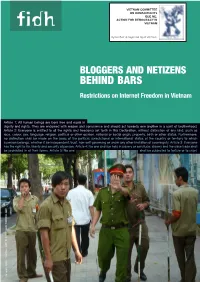

Bloggers and Netizens Behind Bars: Restrictions on Internet Freedom In

VIETNAM COMMITTEE ON HUMAN RIGHTS QUÊ ME: ACTION FOR DEMOCRACY IN VIETNAM Ủy ban Bảo vệ Quyền làm Người Việt Nam BLOGGERS AND NETIZENS BEHIND BARS Restrictions on Internet Freedom in Vietnam Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. Article 2: Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty. Article 3: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person. Article 4: No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms. Article 5: No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, January 2013 / n°603a - AFP PHOTO IAN TIMBERLAKE Cover Photo : A policeman, flanked by local militia members, tries to stop a foreign journalist from taking photos outside the Ho Chi Minh City People’s Court during the trial of a blogger in August 2011 (AFP, Photo Ian Timberlake). 2 / Titre du rapport – FIDH Introduction ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------5 -

Aic Paintings Specialty Group Postprints

1991 AIC PAINTINGS SPECIALTY GROUP POSTPRINTS Papers presented at the Nineteenth Annual Meeting of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works Albuquerque, New Mexico Saturday, June 8,1991. Compiled by Chris Stavroudis The Post-Prints of the Paintings Specialty Group: 1991 is published by the Paintings Specialty Group (PSG) of the American Institute for Conservation of Historical and Artistic Works (AIC). These papers have not been edited and are published as received. Responsibility for the methods and/or materials described herein rests solely with the contributors and these should not be considered official statements of the Paintings Specialty Group or the American Institute for Conservation. The Paintings Specialty Group is an approved division of the American Institute for Conservation of Historical and Artistic Works (AIC) but does not necessarily represent AIC policies or opinions. The Post-Prints of the Paintings Specialty Group: 1991 is distributed to members of the Paintings Specialty Group. Additional copies may be purchased from the American Institute for Conservation of Historical and Artistic Works; 1400 16th Street N.W., Suite 340; Washington, DC 20036. Volume designed on Macintosh using QuarkXPress 3.0 by Lark London Stavroudis. Text printed on Cross Pointe 60 lb. book, an acid-free, recycled paper (50% recycled content, 10% post-consumer waste). Printing and adhesive binding by the Mennonite Publishing House, Scottdale, Pennsylvania. TABLE OF CONTENT S Erastus Salisbury Field, American Folk Painter: 4 His Changing Style And Changing Techniques Michael L. Heslip and James S. Martin The Use of Infra-red Vidicon and Image Digitizing Software in 4 Examining 20th-century Works of Art James Coddington Paintings On Paper: Collaboration Between Paper 11 and Paintings Conservators Daria Keynan and Carol Weingarten Standard Materials for Analysis of Binding Media and 23 GCI Binding Media Library Dusan C. -

Info/How to Examine an Antique Painting.Pdf

How to Examine an Antique Painting by Peter Kostoulakos Before we can talk about the examination process, an overview of how to handle an oil painting is necessary to prevent damage to the work and liability for the appraiser. The checklist below is essential for beginning appraisers to form a methodical approach to examining art in the field without heavy, expensive equipment. Although the information may seem elementary for seasoned appraisers, it can be considered a review with a few tips to organize your observational skills. When inspecting an antique painting, as with any antique, a detailed on the spot, examination should take place. A small checklist covering composition, support, paint layers, varnish, and frame is necessary. Also, a few tools such as a UV lamp, magnifiers, camera, soft brush, cotton swabs, and tape measure are needed. A "behind the scenes" investigation can tell you a great deal about the painting. The name of the artist, title of the painting, canvas maker, date of canvas and stretcher, exhibitions and former owners are some of the things that may be revealed upon close examination. Document your examination with notes and plenty of photographs. Handling Art Older paintings should be thought of as delicate babies. We need to think about the consequences before we pick one up. To prevent acidic oil from our skin to be transferred to paintings and frames, we must cover our hands with gloves. Museum workers have told me that they feel insecure using white, cotton gloves because their grip becomes slippery. I tried the ceremonial gloves used in the military to grip rifles while performing. -

This Version Has the Raw Data in an Appendix)

Accepted for publication in 2020 by the International Journal of Communication, ijoc.org (this version has the raw data in an appendix) Podcasting as Public Media: The Future of U.S. News, Public Affairs and Educational Podcasts PATRICIA AUFDERHEIDE American University, USA DAVID LIEBERMAN The New School, USA ATIKA ALKHALLOUF American University, USA JIJI MAJIRI UGBOMA The New School, USA This article identifies a U.S.-based podcasting ecology as public media, and then examines the threats to its future. It first identifies characteristics of a set of podcasts in the U.S. that allow them to be usefully described as public podcasting. Second, it looks at current business trends in podcasting as platformization proceeds. Third, it identifies threats to public podcasting’s current business practices. Finally, it analyzes responses within public podcasting to the potential threats. It concludes that currently, the public podcast ecology in the U.S. maintains some immunity from the most immediate threats, but that as well there are underappreciated threats to it both internally and externally. Keywords: podcasting, public media, platformization, business trends, public podcasting ecology As U.S. podcasting becomes an increasingly commercially-viable part of the media landscape, are its public-service functions at risk? This article explores that question, in the process postulating that the concept of public podcasting has utility in describing, not only a range of podcasting practices, but an ecology within the larger podcasting ecology—one that permits analysis of both business methods and social practices, one that deserves attention and even protection. This analysis contributes to the burgeoning literature on podcasting by enabling focused research in this area, permitting analysis of the sector in ways that permit thinking about the relationship of mission and business practice sector-wide. -

4X GRAMMY® AWARD WINNING DUO for KING & COUNTRY TO

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 6th, 2021 4x GRAMMY® AWARD WINNING DUO for KING & COUNTRY TO EMBARK ON FIRST ARENA TOUR IN TWO YEARS WITH RELATE | THE 2021 FALL TOUR Click Here to Download Admat Nashville, TENN. – After setting an industry record with six consecutive No. 1 hits, 4x GRAMMY Award winning, platinum-selling duo and Curb | Word Entertainment recording artist for KING & COUNTRY are announcing RELATE | The 2021 Fall Tour. After wowing crowds in 2020 with their Pollstar recognized drive-in theater performances, this 24-date trek will see Joel and Luke Smallbone return to the road in compelling fashion, arranging their electrifying live spectacle for arenas and amphitheaters. BRAND NEW, never performed songs from an upcoming studio project will be featured on the tour’s setlist, along with selections from the duo’s nine No. 1 hits – including “joy.,” “Fix My Eyes,” and the cross-genre multi-week smash “God Only Knows.” This will be fans’ first chance to hear new music straight from the source. for KING & COUNTRY kick things off in Toledo, Ohio on October 7th before wrapping up in Rochester, Minnesota on November 14th. Ticket pre-sale for RELATE | The 2021 Fall Tour starts tomorrow at 10am local time, to access the pre-sale enter the code “RELATE” at the link HERE. Tickets will go on sale to the public July 9th at 10am local time, click HERE for more information. “The thought of hitting the road and seeing you again is a thrilling one,” Joel and Luke Smallbone share in a statement. “Since we were last together, we’ve been hard at work writing and recording new music, which is going to make ‘RELATE | The 2021 Fall Tour’ a particularly special one. -

Mass Media and the Transformation of American Politics Kristine A

Marquette Law Review Volume 77 | Issue 2 Article 7 Mass Media and the Transformation of American Politics Kristine A. Oswald Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Kristine A. Oswald, Mass Media and the Transformation of American Politics, 77 Marq. L. Rev. 385 (2009). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol77/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MASS MEDIA AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICAN POLITICS I. INTRODUCTION The importance of the mass media1 in today's society cannot be over- estimated. Especially in the arena of policy-making, the media's influ- ence has helped shape the development of American government. To more fully understand the political decision-making process in this coun- try it is necessary to understand the media's role in the performance of political officials and institutions. The significance of the media's influ- ence was expressed by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn: "The Press has become the greatest power within Western countries, more powerful than the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary. One would then like to ask: '2 By what law has it been elected and to whom is it responsible?" The importance of the media's power and influence can only be fully appreciated through a complete understanding of who or what the media are. -

Tailoring and Dressm King 5 LINING A. SKIRT Or DRESS Today's Fashions

tailoring and dressm king 5 LINING a. SKIRT or DRESS Today’s fashions and fabrics often call for linings. This raises questions among the home seamstresses regarding types of lining and how to attach these to the garment. Lining serves many purposes. It: 0 gives a professional 100k and adds quality 0 adds body and/or opacity to lightweight or thin fabric 0 gives roundness to structural lines where needed 0 prevents sagging, stretch or “sitting " out” in straight skirts (helps to preserve shape of garment) ' 0 gives longer service to the garment 0 helps to eliminate wrinkles A distinCtion should be made among four sometimes confusing terms: 1. Lining refers to a material that partially or entirely covers the inside of a garment. It is assembled separately as though it were a second garment. It finishes the wrong side of the garment as well as serving the purposes listed C above. For better fit and more strength it should be cut on the same grain as the outer fabric. 2. Underlining is a material which is cut in the shape of the garment pieces. The underlining sections are staystitched to- the corresponding outer fabric sections before any seams are joined. This is especially good for loosely woven or thin fabrics. This treatment is usually called “double fabric con- struction.” It is also called backing or underlay. 3. Interlining ,is usually thought of as giving warmth to a coat as well as giving some shape. The interlining is cut' to match the garment pieces and is placed between the lining and the outer fabric. -

SCIENCE and the MEDIA AMERICAN ACADEMY of ARTS & SCIENCES Science and the Media

SCIENCE AND THE MEDIA AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ARTS & SCIENCES SCIENCE AND THE MEDIA AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ARTS Science and the Media Edited by Donald Kennedy and Geneva Overholser AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ARTS & SCIENCES AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ARTS & SCIENCES Science and the Media Please direct inquiries to: American Academy of Arts and Sciences 136 Irving Street Cambridge, MA 02138-1996 Telephone: 617-576-5000 Fax: 617-576-5050 Email: [email protected] Web: www.amacad.org Science and the Media Edited by Donald Kennedy and Geneva Overholser © 2010 by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences All rights reserved. ISBN#: 0-87724-087-6 The American Academy of Arts and Sciences is grateful to the Annenberg Foundation Trust at Sunnylands for supporting The Media in Society project. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Annenberg Foundation Trust at Sunnylands or the Officers and Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Contents vi Acknowledgments vii Preface 1 Chapter 1 Science and the Media Donald Kennedy 10 Chapter 2 In Your Own Voice Alan Alda 13 Chapter 3 Covering Controversial Science: Improving Reporting on Science and Public Policy Cristine Russell 44 Chapter 4 Civic Scientific Literacy: The Role of the Media in the Electronic Era Jon D. Miller 64 Chapter 5 Managing the Trust Portfolio: Science Public Relations and Social Responsibility Rick E. Borchelt, Lynne T. Friedmann, and Earle Holland 71 Chapter 6 Response to Borchelt, Friedmann, and Holland on Managing the Trust Portfolio: Science Public Relations and Social Responsibility Robert Bazell 74 Chapter 7 The Scientist as Citizen Cornelia Dean 80 Chapter 8 Revitalizing Science Journalism for a Digital Age Alfred Hermida 88 Chapter 9 Responsible Reporting in a Technological Democracy William A. -

Billboard #1 Records

THE BILLBOARD #1 ALBUMS COUNTRY ALBUM SALES DEBUTPEAK ARTIST TITLE LABEL SEL# (1) 5/11/19 1 1. SCOTT, Dylan Nothing To Do Town (EP) Curb HEATSEEKER ALBUMS DEBUTPEAK ARTIST TITLE LABEL SEL# (1) 7/8/95 1 1. PERFECT STRANGER You Have The Right To Remain Silent Curb 77799 (1) 11/3/01 1 2. HOLY, Steve Blue Moon Curb 77972 (1) 5/21/11 1 3. AUGUST, Chris No Far Away Fervent/Curb-Word 888065 MUSIC VIDEO SALES DEBUTPEAK ARTIST TITLE LABEL SEL# (28) 5/8/93 1 1. STEVENS, Ray Comedy Video Classics Curb 77703 (6) 5/7/94 1 2. STEVENS, Ray Live Curb 77706 TOP CATALOG COUNTRY ALBUMS DEBUTPEAK ARTIST TITLE LABEL SEL# (1) 6/15/91 1 1. WILLIAMS, Hank Jr. Greatest Hits Elektra/Curb 60193 (2) 8/21/93 1 2. JUDDS, The Greatest Hits RCA/Curb 8318 (26) 6/19/99 1 3. MCGRAW, Tim Everywhere Curb 77886 (18) 4/1/00 1 4. MESSINA, Jo Dee I'm Alright Curb 77904 (1) 8/17/02 1 5. SOUNDTRACK Coyote Ugly Curb 78703 (54) 12/7/02 1 6. MCGRAW, Tim Greatest Hits Curb 77978 (2) 1/19/08 1 7. MCGRAW, Tim Greatest Hits, Vol. 2: Reflected Curb 78891 (4) 6/16/11 1 8. MCGRAW, Tim Number One Hits Curb 79205 TOP CHRISTIAN ALBUMS DEBUTPEAK ARTIST TITLE LABEL SEL# (35) 9/27/97 1 1. RIMES, LeAnn You Light Up My Life: The Inspirational Album Curb 77885 (35) 10/7/01 1 2. P.O.D. Satellite Atlant/Curb-Word 83496 (5) 6/8/02 1 3.