Playing America's Game: Baseball, Latinos, and the Color Line

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

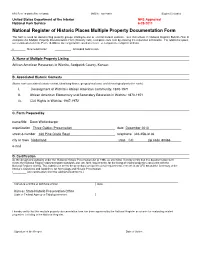

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10-900-b (Rev. 01/2009) OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior NPS Approved National Park Service 6-28-2011 National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items x New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing African American Resources in Wichita, Sedgwick County, Kansas B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) I. Development of Wichita’s African American Community: 1870-1971 II. African American Elementary and Secondary Education in Wichita: 1870-1971 III. Civil Rights in Wichita: 1947-1972 C. Form Prepared by name/title Deon Wolfenbarger organization Three Gables Preservation date December 2010 street & number 320 Pine Glade Road telephone 303-258-3136 city or town Nederland state CO zip code 80466 e-mail D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR 60 and the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. -

Jackie and Campy William C

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and University of Nebraska Press Chapters 2014 Jackie and Campy William C. Kashatus Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples Kashatus, William C., "Jackie and Campy" (2014). University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters. 263. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples/263 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Nebraska Press at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. JACKIE & CAMPY Buy the Book Buy the Book JACKIE & CAMPY Th e Untold Story of Th eir Rocky Relationship and the Breaking of Baseball’s Color Line William C. Kashatus University of Nebraska Press Lincoln and London Buy the Book © 2014 by William C. Kashatus. Portions of chapters 3, 4, and 5 previously appeared in William C. Kashatus, September Swoon: Richie Allen, the 1964 Phillies and Racial Integration (University Park: Penn State Press, 2004). Used with permission. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Kashatus, William C. Jackie and Campy: the untold story of their rocky relationship and the breaking of baseball’s color line / William C. Kashatus. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978- 0- 8032- 4633- 1 (cloth: alk. paper)— isbn 978- 0- 8032- 5447- 3 (epub)— isbn 978- 0- 8032- 5448- 0 (mobi)— isbn 978- 0- 8032- 5446- 6 (pdf) 1. -

History of Civil Rights in the United States: a Bibliography of Resources in the Erwin Library, Wayne Community College

History of Civil Rights in the United States: A Bibliography of Resources in the Erwin Library, Wayne Community College The History of civil rights in the United States is not limited in any way to the struggle to first abolish slavery and then the iniquitous “Jim Crow” laws which became a second enslavement after the end of the American Civil War in 1865. Yet, since that struggle has been so tragically highlighted with such long turmoil and extremes of violence, it has become, ironically perhaps, the source of the country’s greatest triumph, as well as its greatest shame. The assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, who would have sought to guide the reunion of the warring states with a leniency and clear purpose which could possibly have prevented the bitterness that gave rise to the “Jim Crow” aberrations in the Southern communities, seems to have foreshadowed the renewed turmoil after the assassination in 1968 of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who had labored so long to awaken the nation non-violently, but unwaveringly, to its need to reform its laws and attitudes toward the true union of all citizens of the United States, regardless of color. In 2014, we are only a year past the observation of two significant anniversaries in 2013: the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, issued by President Abraham Lincoln in 1863, re-focusing the flagging Union’s purpose on the abolition of slavery as an outcome of the Civil War, and the 50th anniversary of the “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. -

Racial Discrimination in Housing

Cover picture: Members of the NAACP’s Housing Committee create signs in the offices of the Detroit Branch for use in a future demonstration. Unknown photographer, 1962. Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University. (24841) CIVIL RIGHTS IN AMERICA: RACIAL DISCRIMINATION IN HOUSING A National Historic Landmarks Theme Study Prepared by: Organization of American Historians Matthew D. Lassiter Professor of History University of Michigan National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers Consultant Susan Cianci Salvatore Historic Preservation Planner & Project Manager Produced by: The National Historic Landmarks Program Cultural Resources National Park Service US Department of the Interior Washington, DC March 2021 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................... 1 HISTORIC CONTEXTS Part One, 1866–1940: African Americans and the Origins of Residential Segregation ................. 5 • The Reconstruction Era and Urban Migration .................................................................... 6 • Racial Zoning ...................................................................................................................... 8 • Restrictive Racial Covenants ............................................................................................ 10 • White Violence and Ghetto Formation ............................................................................. 13 Part Two, 1848–1945: American -

Dissent Fall 2001

NOTEBOOK Rosa Parks: Angry, Not Tired Peter Dreier cause of my color.’’ Discussing her grandfather, Sylvester Edwards, she wrote, “I remember that sometimes he would call white men by their first names, or their whole names, and not say, he way we learn history shapes ‘Mister.’ How he survived doing all those kinds how we think about the present and of things, and being so outspoken, talking that the future. Consider what most big talk, I don’t know, unless it was because AmericansT know about Rosa Parks, who died he was so white and so close to being one of last October at age ninety-two. them.” In the popular legend, Parks is portrayed In the 1930s, she and her husband, as a tired old seamstress in Montgomery, Ala- Raymond Parks, a barber, raised money for the bama, who, on the spur of the moment after a defense of the Scottsboro Boys, nine young, hard day at work, decided to resist the city’s black men falsely accused of raping two white segregation law by refusing to move to the back women. Involvement in this controversial cause of the bus on December 1, 1955. She is typi- was extremely dangerous for southern blacks. cally revered as a selfless individual who, with In 1943, Parks became one of the first one spontaneous act of courage, triggered the women to join the Montgomery chapter of the bus boycott and became, as she is often called, National Association for the Advancement of “the mother of the civil rights movement.” Colored People and served for many years as Although a number of books—including chapter secretary and director of its youth Taylor Branch’s Parting the Waters, Stewart group. -

MR Everybody's Hero the Jackie Robinson Story Study Guide GZ

Everybody’s Hero: The Jackie Robinson Story A Play with Music by Mad River Theater Works Study Guide for Teachers Discussion Points for Home About the Show At the start of the summer of 1947, television was brand new, the sound barrier had not been broken and baseball was a white man’s game. By the time the fall arrived, all that had changed. President Truman addressed the nation for the first time on TV, Chuck Yeager flew faster than any man ever had and Jackie Robinson became the first African-American to play major league baseball. It was no accident that Jackie Robinson was chosen as the first ballplayer to break the color barrier in the sport known as America’s pastime. There were plenty of good athletes in the Negro Leagues: some maybe even better than Jackie. However, when Branch Rickey decided to add a black person to the Brooklyn Dodgers, he knew that individual had to be special. He had to be strong enough to stand up to the teammates who would ridicule him, the pitchers who would throw at him and the fans who would send him threats. He had to be able to turn the other cheek, to show that he was the bigger man and to prove that he could be everybody’s hero. This play with music by Mad River Theater Works shows the events that shaped Jackie Robinson’s character, his struggle to gain acceptance and the tremendous obstacles he overcame on his way to changing the face of our nation and our national pastime. -

Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination

Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Hamilton, John C. 2013. Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11125122 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination A dissertation presented by Jack Hamilton to The Committee on Higher Degrees in American Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of American Studies Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2013 © 2013 Jack Hamilton All rights reserved. Professor Werner Sollors Jack Hamilton Professor Carol J. Oja Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination Abstract This dissertation explores the interplay of popular music and racial thought in the 1960s, and asks how, when, and why rock and roll music “became white.” By Jimi Hendrix’s death in 1970 the idea of a black man playing electric lead guitar was considered literally remarkable in ways it had not been for Chuck Berry only ten years earlier: employing an interdisciplinary combination of archival research, musical analysis, and critical race theory, this project explains how this happened, and in doing so tells two stories simultaneously. -

African Americans and Baseball, 1900-1947

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2006 "They opened the door too late": African Americans and baseball, 1900-1947 Sarah L. Trembanis College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African History Commons, American Studies Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Trembanis, Sarah L., ""They opened the door too late": African Americans and baseball, 1900-1947" (2006). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623506. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-srkh-wb23 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THEY OPENED THE DOOR TOO LATE” African Americans and Baseball, 1900-1947 A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Lyon Gardiner Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Sarah Lorraine Trembanis 2006 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. APPROVAL SHEET This dissertation is submitted in partial fulfdlment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sarah Lorraine Trembanis Approved by the Committee, August 2006 Kimberley L. PhillinsJPh.D. and Chair Frederick Comey, Ph.D. Cindy Hahamovitch, Ph.D. Charles McGovern, Ph.D eisa Meyer, Ph.D. -

Baseball's Great Experiment: Jackie

Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy by Jules Tygiel (1997) - Not Even Past BOOKS FILMS & MEDIA THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN BLOG TEXAS OUR/STORIES STUDENTS ABOUT 15 MINUTE HISTORY "The past is never dead. It's not even past." William Faulkner NOT EVEN PAST Tweet 0 Like THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy Making History: Houston’s “Spirit of the by Jules Tygiel (1997) Confederacy” by Dolph Briscoe IV Historian Jules Tygiel presents not only an account of Jackie Robinson’s heroic struggle to integrate Major League Baseball, but a larger history of links between African American history, baseball, and the modern civil rights movement. Baseball’s Great Experiment further raises questions about race and sports in our current day. May 06, 2020 More from The Public Historian BOOKS America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States by Erika Lee (2019) April 20, 2020 The integration of baseball in the immediate post-World War II years profoundly impacted American racial attitudes and culture. Baseball, the national pastime and most popular sport at the time, had remained More Books segregated even as football and basketball had begun integrating. Brooklyn Dodgers executive Branch Rickey became convinced that the integration of African Americans into Major League Baseball would serve as both a moral cause and an untapped resource of talented players that could strengthen his DIGITAL HISTORY team. Rickey recruited Jackie Robinson, a former army lieutenant and exceptional athlete who had played numerous sports at UCLA, to initiate his great experiment. Robinson suffered threats, taunts, and Ticha: Digital Archive Review abuse while breaking baseball’s color line in 1947, but performed remarkably on the field, carrying himself https://notevenpast.org/baseballs-great-experiment-jackie-robinson-and-his-legacy-1997/[7/13/2020 10:23:42 AM] Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy by Jules Tygiel (1997) - Not Even Past with a righteous dignity that amazed Americans. -

Jackie Robinson - Early Years

BASEBALL'S COLOR LINE 0. BASEBALL'S COLOR LINE - Story Preface 1. JACKIE ROBINSON - EARLY YEARS 2. JACKIE ROBINSON - WORLD WAR II 3. JACK ROBINSON KEEPS HIS BUS SEAT 4. COURT MARTIAL of JACKIE ROBINSON 5. BASEBALL'S COLOR LINE 6. BRANCH RICKEY MAKES A CHANGE 7. BREAKING the COLOR LINE 8. CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER This image depicts an article from the New York Times, c. 1887, indicating that the St. Louis team - then called the "Browns" - refused to play against a team with "colored men." Image online, courtesy STL Cardinal website. As the nineteenth century drew to a close, African-Americans were forced to play segregated baseball. Sol White (an infielder/outfielder on various teams) documented some of those years (from 1887 through 1903) with his History of Colored Base Ball. In the book’s current edition, the late historian Jerry Malloy included documents like this April 11, 1891 article from Sporting Life magazine: Probably in no other business in America is the color line so finely drawn as in base ball. An African who attempts to put on a uniform and go in among a lot of white players is taking his life in his hands. Were black and white players alsotreated differently by business establishments as they traveled to various towns? From firsthand experience, Sol (a 2006 Hall-of-Fame inductee) tells us that it was even difficult for him, and others similarly situated, to find a place to sleep: The colored player suffers a great inconvenience at times while traveling. All the hotels are generally filled from the cellar to the garret when they strike a town. -

African American Parents Talk to Their Adolescent Sons About Racism

Colorblind and Colorlined: African American Parents Talk to Their Adolescent Sons About Racism The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Diaquoi, Raygine C. 2015. Colorblind and Colorlined: African American Parents Talk to Their Adolescent Sons About Racism. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard Graduate School of Education. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:16461058 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Colorblind and colorlined: African American parents talk to their adolescent sons about racism Raygine Coutard DiAquoi Dr. Daren Graves Dr. Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot Dr. Janie Ward A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Education of Harvard University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education 2015 ©2015 Raygine DiAquoi All Rights Reserved A love letter to Black families i Acknowledgements To everyone who has supported me along this journey iv Table of Contents Introduction 1 Background and context 6 Problem statement 15 Statement of purpose and research questions 16 Research approach 16 Assumptions 18 The researcher 19 Terms and definitions used throughout this study 27 Literature review 28 What we think we know about Black boys 29 What we fail to consider -

Is Affirmative Action Reverse Discrimination?

Is Affirmative Action Reverse Discrimination? By Dr. Maura Cullen Claims of reverse discrimination have been around for a while; however, recent events have brought it back into the forefront. The election of our first black President, Barack Obama, the appointment of Sonia Sotomayo, the first Latina to serve on the United States Supreme Court and the last four Secretaries of State were two white women, a black women and black man. Some white people are claiming that white men are the ones who are currently being discriminated against. However, the numbers tell the truth. There are nine Supreme Court justices; seven of them are white men. There have been 44 Presidents, 43 of them have been white men. I think it’s a sure bet that we will see at least one white man as President again in the years to come. I recall seeing a photo of then Presidential candidate John Edwards on the cover of Esquire magazine, with the caption, “Can a White man still be President?” Instead of asking such a silly question, we should be asking ourselves why have there only been one non- white President and no women? I recall reading a quote by Barry Switzer, “Some people are born on third base and go through life thinking they’ve hit a triple”. That profound statement truly sums up the essence of racial privilege and what it is to be white in the United States. It demonstrates that some people are given a head start while others have to work much harder to get to the same place.