African Americans and Baseball, 1900-1947

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Preview

DETROIT TIGERS’ 4 GREATEST HITTERS Table of CONTENTS Contents Warm-Up, with a Side of Dedications ....................................................... 1 The Ty Cobb Birthplace Pilgrimage ......................................................... 9 1 Out of the Blocks—Into the Bleachers .............................................. 19 2 Quadruple Crown—Four’s Company, Five’s a Multitude ..................... 29 [Gates] Brown vs. Hot Dog .......................................................................................... 30 Prince Fielder Fields Macho Nacho ............................................................................. 30 Dangerfield Dangers .................................................................................................... 31 #1 Latino Hitters, Bar None ........................................................................................ 32 3 Hitting Prof Ted Williams, and the MACHO-METER ......................... 39 The MACHO-METER ..................................................................... 40 4 Miguel Cabrera, Knothole Kids, and the World’s Prettiest Girls ........... 47 Ty Cobb and the Presidential Passing Lane ................................................................. 49 The First Hammerin’ Hank—The Bronx’s Hank Greenberg ..................................... 50 Baseball and Heightism ............................................................................................... 53 One Amazing Baseball Record That Will Never Be Broken ...................................... -

Negro League Teams

From the Negro Leagues to the Major Leagues: How and Why Major League Baseball Integrated and the Impact of Racial Integration on Three Negro League Teams. Christopher Frakes Advisor: Dr. Jerome Gillen Thesis submitted to the Honors Program, Saint Peter's College March 28, 2011 Christopher Frakes Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction 3 Chapter 2: Kansas City Monarchs 6 Chapter 3: Homestead Grays 15 Chapter 4: Birmingham Black Barons 24 Chapter 5: Integration 29 Chapter 6: Conclusion 37 Appendix I: Players that played both Negro and Major Leagues 41 Appendix II: Timeline for Integration 45 Bibliography: 47 2 Chapter 1: Introduction From the late 19th century until 1947, Major League Baseball (MLB, the Majors, the Show or the Big Show) was segregated. During those years, African Americans played in the Negro Leagues and were not allowed to play in either the MLB or the minor league affiliates of the Major League teams (the Minor Leagues). The Negro Leagues existed as a separate entity from the Major Leagues and though structured similarly to MLB, the leagues were not equal. The objective of my thesis is to cover how and why MLB integrated and the impact of MLB’s racial integration on three prominent Negro League teams. The thesis will begin with a review of the three Negro League teams that produced the most future Major Leaguers. I will review the rise of those teams to the top of the Negro Leagues and then the decline of each team after its superstar(s) moved over to the Major Leagues when MLB integrated. -

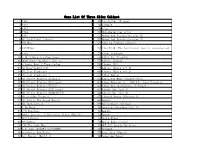

2475 in 1 Game List

Game List Of Three Sides Cabinet 1 1941 47 Air Gallet (Taiwan) 2 1942 48 Airwolf 3 1943 49 Ajax 4 1944 50 Akkanbeder(ver 2.5j) 5 1945 51 Akuma-Jou Dracula(version N) 6 10 Yard Fight (Japan) 52 Akuma-Jou Dracula(version P) 7 1943kai 53 Ales no Tsubasa (Japan) 8 1945Plus 54 Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars (set 2, unprotected) 9 19xx 55 Alien Syndrome 10 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge 56 Alien vs. Predator 11 2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 57 Aliens (Japan) 12 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex 58 Aliens (US) 13 3D_Beastorizer(US) 59 Aliens (World set 1) 14 3D_Star Gladiator 60 Aliens (World set 2) 15 3D_Star Gladiator 2 61 Alley Master 16 3D_Street Fighter EX(Asia) 62 Alligator Hunt (unprotected) 17 3D_Street Fighter EX(Japan) 63 Alpha Mission II / ASO II - Last Guardian 18 3D_Street Fighter EX(US) 64 Alpha One (prototype, 3 lives) 19 3D_Street Fighter EX2(Japan) 65 Alpine Ski (set 1) 20 3D_Street Fighter EX2PLUS(US) 66 Alpine Ski (set 2) 21 3D_Strider Hiryu 2 67 Altered Beast (Version 1) 22 3D_Tetris The Grand Master 68 Ambush 23 3D_Toshinden 2 69 Ameisenbaer (German) 24 4 En Raya 70 American Speedway (set 1) 25 4-D Warriors 71 Amidar 26 64th. Street - A Detective Story (World) 72 Amigo 27 800 Fathoms 73 Andro Dunos 28 88 Games! 74 Angel Kids (Japan) 29 '99 The Last War 75 APB-All Points Bulletin 30 A.B. Cop (FD1094 317-0169b) 76 Appoooh 31 Acrobatic Dog_Fight 77 Aqua Jack (World) 32 Act-Fancer (World 1) 78 Aquarium(Japan) 33 Act-Fancer (World 2) 79 Arabian Act-Fancer Cybernetick Hyper Weapon (Japan 34 80 Arabian (Atari) revision 1) 35 Action Fighter 81 Arabian -

Ahc CAR 015 017 007-Access.Pdf

•f THE...i!jEW===¥i^i?rmiES, DAY, OCTOBER 22, 19M. ly for Per^i^sion to Shift to Atlanta Sra ves/Will Ask Leag ^ ^ " ' NANCE DOEMOB, Ewbank Calls for Top Jet Effort ISl A gainstUnbeatenBillsSaturday ELECTRONICS SYRACUSE By DEANE McGOWEN llback, a DisappointmEnt The Buffalo Bills, the only un The Bills also lead in total of defeated team in professional fense—397 yards a game, 254 2 Years, Now at Pea football, were the primary topic yards passing and 143 rushing. statement Given Out Amid of conversation at the New Jets Have the Power By ALLISON DANZIG York Jets' weekly luncheon yes High Confusion — Giles Calls Special to The New York Times terday. The Jets' tough defense plus SYRACUSE, Oct. 21 — Af The Jets go to Buffalo to face the running of Matt Snell and Tuner complete the passing of Dick Wood are Owners to Meeting Here two years of frustration, the Eastern Division leaders of being counted on by Ewbank to once Nance is finally performing the American Football League Saturday night, and for the handle the Bills. like another Jim Brown, find Snell, the rookie fullback who 0 watt Stereo Amplifier ModelXA — CHICAGO, Oct. 21 (AP)— Syracuse finds itself among the charges of Weeb Ewbank the ^udio Net $159.95 CQR OA pulverizes tacklers with his in New low price i^WviUU The Milwaukee Braves board of top college football teams ill the game will be the moment of stant take-off running and his directors voted today to request nation The Orange is leading truth. second-effort power, is the New .mbert "Their personnel is excellent AM, FM. -

Harlem Globetrotters Adrian Maher – Writer/Director 1

Unsung Hollywood: Harlem Globetrotters Adrian Maher – Writer/Director 1 UNSUNG HOLLYWOOD: Writer/Director/Producer: Adrian Maher HARLEM GLOBETROTTERS COLD OPEN Tape 023 Ben Green The style of the NBA today goes straight back, uh, to the Harlem Globetrotters…. Magic Johnson and Showtime that was Globetrotter basketball. Tape 030 Mannie Jackson [01:04:17] The Harlem Globetrotters are arguably the best known sports franchise ….. probably one of the best known brands in the world. Tape 028 Kevin Frazier [16:13:32] The Harlem Globetrotters are …. a team that revolutionized basketball…There may not be Black basketball without the Harlem Globetrotters. Tape 001 Sweet Lou Dunbar [01:10:28] Abe Saperstein, he's only about this tall……he had these five guys from the south side of Chicago, they….. all crammed into ….. this one small car. And, they'd travel. Tape 030 Mannie Jackson [01:20:06] Abe was a showman….. Tape 033 Mannie Jackson (04:18:53) he’s the first person that really recognized that sports and entertainment were blended. Tape 018 Kevin “Special K” Daly [19:01:53] back in the day, uh, because of the racism that was going on the Harlem Globetrotters couldn’t stay at the regular hotel so they had to sleep in jail sometimes or barns, in the car, slaughterhouses Tape 034 Bijan Bayne [09:37:30] the Globetrotters were prophets……But they were aliens in their own land. Tape 007 Curly Neal [04:21:26] we invented the slam dunk ….., the ally-oop shot which is very famous and….between the legs, passes Tape 030 Mannie Jackson [01:21:33] They made the game look so easy, they did things so fast it looked magical…. -

FROM BULLDOGS to SUN DEVILS the EARLY YEARS ASU BASEBALL 1907-1958 Year ...Record

THE TRADITION CONTINUES ASUBASEBALL 2005 2005 SUN DEVIL BASEBALL 2 There comes a time in a little boy’s life when baseball is introduced to him. Thus begins the long journey for those meant to play the game at a higher level, for those who love the game so much they strive to be a part of its history. Sun Devil Baseball! NCAA NATIONAL CHAMPIONS: 1965, 1967, 1969, 1977, 1981 2005 SUN DEVIL BASEBALL 3 ASU AND THE GOLDEN SPIKES AWARD > For the past 26 years, USA Baseball has honored the top amateur baseball player in the country with the Golden Spikes Award. (See winners box.) The award is presented each year to the player who exhibits exceptional athletic ability and exemplary sportsmanship. Past winners of this prestigious award include current Major League Baseball stars J. D. Drew, Pat Burrell, Jason Varitek, Jason Jennings and Mark Prior. > Arizona State’s Bob Horner won the inaugural award in 1978 after hitting .412 with 20 doubles and 25 RBI. Oddibe McDowell (1984) and Mike Kelly (1991) also won the award. > Dustin Pedroia was named one of five finalists for the 2004 Golden Spikes Award. He became the seventh all-time final- ist from ASU, including Horner (1978), McDowell (1984), Kelly (1990), Kelly (1991), Paul Lo Duca (1993) and Jacob Cruz (1994). ODDIBE MCDOWELL > With three Golden Spikes winners, ASU ranks tied for first with Florida State and Cal State Fullerton as the schools with the most players to have earned college baseball’s top honor. BOB HORNER GOLDEN SPIKES AWARD WINNERS 2004 Jered Weaver Long Beach State 2003 Rickie Weeks Southern 2002 Khalil Greene Clemson 2001 Mark Prior Southern California 2000 Kip Bouknight South Carolina 1999 Jason Jennings Baylor 1998 Pat Burrell Miami 1997 J.D. -

New Bingo Rules

January 2018 A Message From Alfonso D. Royal, III Charitable Bingo Operations Director New Bingo Rules At the December 7, 2017 open meeting of the Texas Lottery Commission, the Commission voted to adopt amendments (rule changes) to 16 TAC §§402.400 (General Licensing Provisions), 402.401 (Temporary License), 402.402 (Registry of Bingo Workers), 402.404 (License and Registration Fees), 402.405 (Temporary Authorization), 402.407 (Unit Manager), 402.410 (Amendments of a License – General Provisions), 402.411 (License Renewal), 402.413 (Military Service Members, Military Veterans, and Military Spouses), 402.420 (Qualifications and Requirements for Conductor’s License), 402.424 (Amendments of a License by Electronic Mail, Telephone or Facsimile), 402.422 (Amendment to a Regular License to Conduct Charitable Bingo), and 402.603 (Bond or Other Security) of the Commission’s charitable bingo rules. The purpose of the rule changes is to implement the statutory changes required by the newly-enacted legislation of H.B. 2578, S.B. 549, and S.B. 2065 from the Regular Session of the 85th Texas Legislature. The rule changes remove all references to bingo conductor and bingo worker fees, while revising the license application and renewal process. In addition, the changes facilitate the requirement that the Commission retain a portion of the bingo prize fees otherwise allocable to counties and municipalities to fund the administration of the charitable bingo program. Further, the rule changes allow commercial lessors, Inside This Message distributors and manufacturers to recover up to Bingo Training Program ................................................... 2 half of their application fee if they withdraw their 24/7 Access to Card-minding Systems ......................... -

Rct-Flyer-2021-Apr-3

Royal Coach Tours & Cruises Phone 386-788-0208 Marcya Wantuch – President & Accredited Cruise Counsellor 1648 Taylor Rd. # 505, Port Orange, FL 32128 OFFICE HOURS: MON.-THU. 9:00AM to 3:00PM & SAT. & SUN. CLOSED but please leave a Message. WEB SITE: royalcoachtours.com EMAIL: [email protected] Winner of News Journals Stars of the South - 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010 - Best Bus Trips, Tours & Cruises Winner of News Journals Daytona’s Readers Choice Award - 2014 - Best Motorcoach Tours Hometown News Winner Reader’s Choice Awards 2012 Through 2019 For Best Motorcoach Tours & Travel Agency Celebrating 28 YEARS in Business in Volusia County/ 41 Years Group Travel Experience Accredited Cruise Counsellor - Cruise Lines Int’l. Assoc. Florida Licensed Travel Insurance Agent / Florida Seller of Travel Lic. #24522 “When we support small businesses, we support our community” APR. 3, 2021 aA “As far as the virus is concerned, we have two choices: We can allow it to dominate us, or we can learn as much as we can about it and we can learn how to live with it in a safe, prescribed manner.” Dr. Ben Carson RESERVATIONS REQUIRED ON ALL TOURS & CRUISES HOW TO BOOK: PLEASE CALL OUR OFFICE FIRST to inquiry about availability and to book your seat. Many of our tours sell out quickly! Seats are assigned from the front of the Bus and at the Show, according to when you pay. We must receive your check within 14 days of reserving your seat. A Tour Confirmation will be emailed to you the same day we receive payment, containing all tour and departure information. -

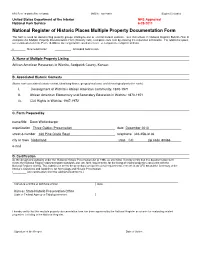

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10-900-b (Rev. 01/2009) OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior NPS Approved National Park Service 6-28-2011 National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items x New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing African American Resources in Wichita, Sedgwick County, Kansas B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) I. Development of Wichita’s African American Community: 1870-1971 II. African American Elementary and Secondary Education in Wichita: 1870-1971 III. Civil Rights in Wichita: 1947-1972 C. Form Prepared by name/title Deon Wolfenbarger organization Three Gables Preservation date December 2010 street & number 320 Pine Glade Road telephone 303-258-3136 city or town Nederland state CO zip code 80466 e-mail D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR 60 and the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. -

Baseball Cyclopedia

' Class J^V gG3 Book . L 3 - CoKyiigtit]^?-LLO ^ CORfRIGHT DEPOSIT. The Baseball Cyclopedia By ERNEST J. LANIGAN Price 75c. PUBLISHED BY THE BASEBALL MAGAZINE COMPANY 70 FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK CITY BALL PLAYER ART POSTERS FREE WITH A 1 YEAR SUBSCRIPTION TO BASEBALL MAGAZINE Handsome Posters in Sepia Brown on Coated Stock P 1% Pp Any 6 Posters with one Yearly Subscription at r KtlL $2.00 (Canada $2.00, Foreign $2.50) if order is sent DiRECT TO OUR OFFICE Group Posters 1921 ''GIANTS," 1921 ''YANKEES" and 1921 PITTSBURGH "PIRATES" 1320 CLEVELAND ''INDIANS'' 1920 BROOKLYN TEAM 1919 CINCINNATI ''REDS" AND "WHITE SOX'' 1917 WHITE SOX—GIANTS 1916 RED SOX—BROOKLYN—PHILLIES 1915 BRAVES-ST. LOUIS (N) CUBS-CINCINNATI—YANKEES- DETROIT—CLEVELAND—ST. LOUIS (A)—CHI. FEDS. INDIVIDUAL POSTERS of the following—25c Each, 6 for 50c, or 12 for $1.00 ALEXANDER CDVELESKIE HERZOG MARANVILLE ROBERTSON SPEAKER BAGBY CRAWFORD HOOPER MARQUARD ROUSH TYLER BAKER DAUBERT HORNSBY MAHY RUCKER VAUGHN BANCROFT DOUGLAS HOYT MAYS RUDOLPH VEACH BARRY DOYLE JAMES McGRAW RUETHER WAGNER BENDER ELLER JENNINGS MgINNIS RUSSILL WAMBSGANSS BURNS EVERS JOHNSON McNALLY RUTH WARD BUSH FABER JONES BOB MEUSEL SCHALK WHEAT CAREY FLETCHER KAUFF "IRISH" MEUSEL SCHAN6 ROSS YOUNG CHANCE FRISCH KELLY MEYERS SCHMIDT CHENEY GARDNER KERR MORAN SCHUPP COBB GOWDY LAJOIE "HY" MYERS SISLER COLLINS GRIMES LEWIS NEHF ELMER SMITH CONNOLLY GROH MACK S. O'NEILL "SHERRY" SMITH COOPER HEILMANN MAILS PLANK SNYDER COUPON BASEBALL MAGAZINE CO., 70 Fifth Ave., New York Gentlemen:—Enclosed is $2.00 (Canadian $2.00, Foreign $2.50) for 1 year's subscription to the BASEBALL MAGAZINE. -

The History of Baseball's Antitrust Exemption, 9 Marq

Marquette Sports Law Review Volume 9 Article 7 Issue 2 Spring Before the Flood: The iH story of Baseball's Antitrust Exemption Roger I. Abrams Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw Part of the Entertainment and Sports Law Commons Repository Citation Roger I. Abrams, Before the Flood: The History of Baseball's Antitrust Exemption, 9 Marq. Sports L. J. 307 (1999) Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw/vol9/iss2/7 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYMPOSIUM: THE CURT FLOOD ACT BEFORE THE FLOOD: THE HISTORY OF BASEBALL'S ANTITRUST EXEMPTION ROGER I. ABRAMS* "I want to thank you for making this day necessary" -Yogi Berra on Yogi Berra Fan Appreciation Day in St. Louis (1947) As we celebrate the enactment of the Curt Flood Act of 1998 in this festschrift, we should not forget the lessons to be learned from the legal events which made this watershed legislation necessary. Baseball is a game for the ages, and the Supreme Court's decisions exempting the baseball business from the nation's antitrust laws are archaic reminders of judicial decision making at its arthritic worst. However, the opinions are marvelous teaching tools for inchoate lawyers who will administer the justice system for many legal seasons to come. The new federal stat- ute does nothing to erase this judicial embarrassment, except, of course, to overrule a remarkable line of cases: Federal Baseball,' Toolson,2 and Flood? I. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. IDgher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & HoweU Information Compaiy 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 OUTSIDE THE LINES: THE AFRICAN AMERICAN STRUGGLE TO PARTICIPATE IN PROFESSIONAL FOOTBALL, 1904-1962 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State U niversity By Charles Kenyatta Ross, B.A., M.A.