A Spectacle of Dust

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KILLING BONO a Nick Hamm Film

KILLING BONO A Nick Hamm Film Production Notes Due for Release in UK: 1st April 2011 Running Time: 114 mins Killing Bono | Production Notes Press Quotes: Short Synopsis: KILLING BONO is a rock n’ roll comedy about two Irish brothers struggling to forge their path through the 1980’s music scene… whilst the meteoric rise to fame of their old school pals U2 only serves to cast them deeper into the shadows. Long Synopsis: Neil McCormick (Ben Barnes) always knew he’d be famous. A young Irish songwriter and budding genius, nothing less than a life of rock n’ roll stardom will do. But there’s only room for one singer in school band The Hype and his friend Paul’s already bagged the job. So Neil forms his own band with his brother Ivan (Robert Sheehan), determined to leave The Hype in his wake. There’s only one problem: The Hype have changed their name. To ‘U2’. And Paul (Martin McCann) has turned into ‘Bono’. Naturally there’s only one option for Neil: become bigger than U2. The brothers head to London in their quest for fame, but they are blighted by the injustices of the music industry, and their every action is dwarfed by the soaring success of their old school rivals. Then, just as they land some success of their own, Ivan discovers the shocking truth behind Neil’s rivalry with U2, and it threatens to destroy everything. As his rock n’ roll dream crashes and burns, Neil feels like his failure is directly linked to Bono’s success. -

March 2002 50P

Community Voice of the Strettons March 2002 50p Pete Postlethwaite plays Scaramouche Jones at Church Stretton School Arts Festival Pre-view . 3 South Shropshire Local Plan . 5 Health Care out of Hours . 7 Town Council . 18 Churches . 24 - 27 Library Storytime . 30 Whitewater Rafting . 32 Children’s page . 34 Supported by West Midlands Co-operative Society Limited, Church Stretton Town Council, Shropshire Rural Development Programme, Strettons Civic Society and Well, Well, Well (UK) Ltd. March 2002 mag 1 19/2/02 11:59 am STRETTON FOCUS This month’s cover (founded 1967) ur own Pete Postlethwaite brings his one-man Average monthly sales: 1,368 copies. stage show Scaramouche Jones to Church Stretton (About 62% of households in Church Stretton) Oprior to a National and International tour. He will be performing in the new auditorium of Church Chairman: Dr Martin Plumptre . 723595 Stretton School on Friday 8th and Saturday 9th March. Vice Chairman: David Jandrell . 724531 In Scaramouche Jones, Pete Editors: Peggy Simmonds . 724117 plays the ageing circus Jill Turner Jones . 724371 clown who sits backstage Design/Layout: Barrie Raynor . 723928 doing a crossword and Paul Miller . 724596 refl ecting upon the Rowland Jackson . 722390 extraordinary experiences Distribution: David Jandrell . 724531 which have made him Advertising: Len Bolton . 724579 who and what he is, his Treasurer: John Wainwright . 722823 life on the road, and the Secretary: Janet Plumptre . 723595 father he never knew. Advertisements. Rates for block and occasional Pete Postlethwaite was advertisements may be obtained (send s.a.e.) from the born in 1945 in Warrington Advertising Manager, Len Bolton, ‘Oakhurst’, Hazler and has lived in Minton Road, Church Stretton, SY6 7AQ, Tel: 01694 724579 to for the past 13 years. -

Page 1 of 562 JEK James and Elizabeth Knowlson Collection This Catalogue Is Based on the Listing of the Collection by James

University Museums and Special Collections Service JEK James and Elizabeth Knowlson Collection This catalogue is based on the listing of the collection by James and Elizabeth Knowlson 1906-2010 JEK A Research material created by James and Elizabeth Knowlson JEK A/1 Material relating to Samuel Beckett JEK A/1/1 Beckett family material JEK A/1/1/1 Folder of Birth Certificates, Parish registers and Army records Consists of a copy of the Beckett Family tree from Horner Beckett, a rubbing of the plaque on William Beckett’s Swimming Cup, birth certificates of the Roes and the Becketts, including Samuel Beckett, his brother, mother and father and photograph of the Paris Register Tullow Parish Church and research information gathered by Suzanne Pegley Page 1 of 562 University Museums and Special Collections Service James Knowlson note: Detailed information from Suzanne Pegley who researched for James and Elizabeth Knowlson the families of both the Roes – Beckett’s mother was a Roe - and the Becketts in the records of the Church Body Library, St Peter’s Parish, City of Dublin, St Mary’s Church Leixlip, the Memorial Registry of Deeds, etc. Very detailed results. 2 folders 1800s-1990s JEK A/1/1/2 Folder entitled May Beckett’s appointment as a nurse Consists of correspondence James Knowlson note: Inconclusive actually 1 folder 1990s JEK A/1/1/3 Folder entitled Edward Beckett Consists of correspondence James Knowlson note: Beckett’s nephew with much interesting information. 1 folder 1990s-2000s JEK A/1/1/4 Folder entitled Caroline Beckett Murphy Consists -

Cast and Crew in Association with Classical Kicks Productions and EB

Cast and Crew Emily Blacksell—Producer, Director and Writer Emily’s 18-year career in the entertainment sector has seen her assist, support, and represent some of the legendary figures of their respective fields both in the UK and internationally, namely the late John Barton CBE, the late Sir Peter Hall, Sir Paul McCartney and Sally Greene OBE. She has worked for world-renowned organisations and venues including the RSC, MPL Communications Ltd., the Old Vic Theatre, Old Vic Productions (now Greene Light Stage), Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club, and Bristol Old Vic Theatre, granting her extraordinary access to, and the experience of working with, globally recognised creative teams and artists on diverse projects and creative ventures. These include Tantalus (USA and Europe), Billy Elliot the Musical (worldwide), five world tours, four album releases, and six book publications during her five years as Assistant to Sir Paul McCartney, and eight seasons at the Old Vic Theatre – a period that included the groundbreaking three-year BAM/Old Vic/Sam Mendes Bridge Project collaboration. Emily received her creative and academic training from the Guildhall School of Music and Drama Junior department where she studied violin and voice, and the University of Birmingham where she read English and Drama. Her passion for music specifically, and performance in general, has informed her own practice and enabled her to work creatively as a director, assistant director, and producer across theatre, opera, digital platforms, and film. As Producer: WillShake Henry V (Short Form Film Company) featuring Tom Hiddleston; Theatre Lives (Digital Theatre+) featuring Dame Julie Walters, Imelda Staunton, Juliet Stevenson, Adrian Lester, and Michael Grandage; Producer & Project Manager Peter O’Toole Memorial (Old Vic Theatre, London); Producer & Co-Curator - with Tom Morris and John Caird - Bristol Old Vic 250th Anniversary Gala. -

Irish Movies: a Renaissance

There is the famously Irish instinct for dealing with human eccentricity as well as the whimsical and magical. Irish Movies: a Renaissance Name of the Father" and "Michael Collins," you're right. There is an "Irish spring" happening in the cin- ema, but it has nothing lo do with Colgate-Palmo- live or bath soap. These are just a few of the major Irish films that have been accessible to American audiences in theaters during the 199O's. Many are available on video, as are a score of other titles from the last decade, some familiar, some not. like "Cal," "Mona Lisa," "The Field," "Hear My Song," "The Playboys." "The Commitments," "The Snapper," "Widow's Peak," "Frankie Starlight," "Circle of Friends," "Into the West." They're all "Irish" in the sense that they're about the Irish, substantially pro- duced in Ireland, and/or (more and more common- ly) created by Irish companies and talent. "Frankie Starlight," for example, is produced by Irishman Noel Pearson but adapted from American Chet Raymo's novel. The Dork of Cork. It's abtuit a dwarf who grows up in lieland after World War II, the son of a Frenchwoman and an American G.I., discovers astronomy, becomes a famous author and finds true love. It was made mostly in Ireland with an international cast directed by Michael Lindsay- Hogg, who. although English, is the accomplished son (he directed the "Brideshead Revisited" minis- eries for British television) of the durable Irish-bom actress Géraldine Fitzgerald. Jim Sheridan's 1989 Irish film. My Left Foot, brought Another chaiacteristic of these films is that, for Academy Awards to Brenda Fricker (left), as the mother of the most part, they have a charm and humanity, an Christy Brown, who is played by Daniel Day-Lewis, winner infectious, "real people" quality that distinguishes of the Best Actor award. -

Kate Sanderson, Freelance Consultant with Jon Bradfield

Arts Marketing Association Why? AMA Conference 2008 Kate Sanderson, Freelance Consultant with Jon Bradfield, Marketing Manager, Out of Joint and Laura Arends, Marketing Campaigns Manager, Liverpool Everyman and Playhouse Long distance relationships – jointly developing relevant communications Kate Sanderson started her marketing career in insurance before moving into the arts. After a spell as marketing manager at an arts centre in Lincolnshire she moved to the West Yorkshire Playhouse where she worked for nine years, being promoted to director of communications and managing a team of 25. Since 2006 she has been a freelance consultant and professional trainer. She is director of TMA’s Essentials of Marketing Course (Druidstone), directed the first Druidstone Northern Ireland and set up the TMA’s new Strategic Marketing course. She is currently managing a series of benchmarking projects involving 50 UK organisations for ADUK. Jon Bradfield began his career at Birmingham Royal Ballet and is marketing manager for Out of Joint, the new writing touring company. He also looks after marketing for Crouch End Festival Chorus which performs regularly at the Barbican and has done marketing and graphic design for productions at the Drill Hall and Southwark Playhouse and for Two’s Company. Laura Arends is marketing campaigns manager for Liverpool Everyman and Playhouse. She began her career as communications sabbatical for Kent Students’ Union before spending a year in Sicily teaching English and Drama. After three years working in sales and marketing for the international logistics industry she joined the Everyman, originally as marketing officer. She is the CIM arts ambassador for Merseyside Branch. -

The Rector Writes…. to Me One of the Most Moving Encounters with Jesus

The Rector writes…. To me one of the most moving encounters with Jesus recorded in the Gospels is when a number of Greeks, we are told, approached the disciples in northern Galilee with the words “Sir, we would see Jesus?” What lay behind that? Evidently, the fame of Jesus had spread to their community and they travelled to learn more. They had heard that this man and his message were important and mattered to them. Is the question “Sir, we would see Jesus?” one that we would ask, does the question resonate with us today? Well I hope it does and I am sure it does for anyone reading this editorial! But can Jesus be found and is it possible to know more about him? This coming month March sees the beginning of Lent, rather late this year, it has to be said! Easter Sunday this year is not until 24 April…the latest possible day for Easter is 25 April. For those who like to know these things the next Easter Sunday on 24 April is 2095 and for 25 April 2038! Back to “Sir we would see Jesus?” yes we can see Jesus or at least find out more about him and so meet him better in prayer and meditation. How? Well, as I say, Lent approaches us when we remember Our Lord‟s time in the Wilderness, and, as usual, we will be having Lent Groups which provide a marvelous opportunity to find out more about our faith in Jesus. Ash Wednesday is on Wednesday 9 March so on Wednesday afternoons thereafter there will be a Lent Group meeting in the Rectory, using the new York course “Rich Inheritance: Jesus‟ Legacy of Love” and there will be a Lent course in Churchstoke too (details elsewhere in the Churchstoke section) “Sir we would see Jesus? “can also be answered in the new Bishop of Ludlow‟s course “Marking Lent”, copies of which the Rector has. -

NICK PERRY Current

NICK PERRY Current: PLAN A: original feature selected for eQuinoxe Europe summer programme 2014. AFTER MACBETH: spec feature screenplay. Director Charles McDougall. MOLL the TV version: optioned film and TV rights to Kindle. LONDON PARTICULAR: three-part play for BBC Radio 4 drama. PRODUCED CREDITS BABELSBERG BABYLON: five-part original for BBC Radio 4 drama. TX July 2020. THE BATTLE OF SAN PIETRO: original play for BBC Radio 4 drama. TX May 2019. ERIC AMBLER ADAPTATIONS - EPITAPH FOR A SPY & JOURNEY INTO FEAR: BBC Radio 4 drama. TX April 2019. THE CONFIDENTIAL AGENT: two-part original BBC Radio 4 drama. TX October 2016 MOLL FLANDERS: two-part dramatisation of Daniel Defoe’s novel for BBC Radio 4 star- ing Jessica Hynes and Ben Miles. TX July 2016. Repeated 2017. NOVEMBER DEAD LIST 2: sequel to his five-part original BBC R4 drama. TX February 2016 THE SHOOTIST: BBC R4 adaptation of the novel by Glendon Swarthout, starring Brian Cox. TX October 2014 NOVEMBER DEAD LIST: five-part original BBC R4 drama. TX January 2014 HE DIED WITH HIS EYES OPEN – 3 x 30’ dramatisation of Derek Raymond’s novel for BBC R4/Sasha Yevtushenko TX October 2013 LONDON BRIDGE: part of the ‘Dangerous Visions’ season for BBC R4/Sasha Yev- tuphenko. TX June 2013 JACK’S RETURN HOME: 4 x 30’ dramatisation of Ted Lewis's British crime classic. TX August/September 2012. REFEREE: written original radio play for BBC R4/Sasha Yevtuphenko. TX May 2011. PLANET B: Wrote an episode of second series of sci-fi drama for BBC7. -

Signs A-B Rieal

Ciij lights up Brighton's life, it gives it hope 3 I Community Newspaper Company • www.allstonbrightontab.com FRIDAY, DECEMBER 9, 2005 Vol. 10, No. 18 40 Pages 3 Sections 75¢ NYET,NYET,NYET APARTMENTS Signs A-B rieal estate marketI finally cooling I By Jonathan Schwab CORRESPONOENT "Now it seems like eal estate agents and bro the buyer's market kers in Allston-Brighton R have different views on has finally revived." the state of the economy, region ally and nationally. Mattljiew Bless Danyl Collings, a broker for Marquis Real Estate General in the real estate business, he has Motors Acceptance Corp., said seen tremendqus change in terms that, as a whole, Boston is a of what the ddllar can buy. buyer 's market because interest rates are climbing. pqcesup Collings, who has lately been Back in _ tJie early 1990s, selling mostly condominiums, Collins said, "You could have said the economy has improved bought probably a street for what significantly since the end of you could have now [for a 2004. house]." "Prices have to come down if Collins, who has been the interest rates come up," he said. manager of ~arquis Real Estate "I think the economy is doing GMAC for six years, added the pretty well." PHOTO BY ZNIA TZANEV market favor~ buyers rather than Retired Gen. Alexander Yoronov, standing In Sldlaw Road Park, Is part of a group of Russian World War II vets pushing for a World War Comparing numbers in 2005 to semrs now, and agreed with II memorlal somewhere In Chestnut Hill. -

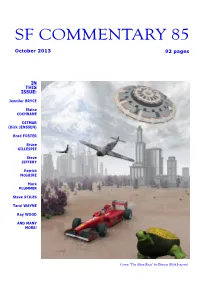

Sf Commentary 85

SF COMMENTARY 85 October 2013 92 pages IN THIS ISSUE: Jennifer BRYCE Elaine COCHRANE DITMAR (Dick JENSSEN) Brad FOSTER Bruce GILLESPIE Steve JEFFERY Patrick McGUIRE Mark PLUMMER Steve STILES Taral WAYNE Ray WOOD AND MANY MORE! Cover: ‘The Alien Race’ by Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) SF COMMENTARY 85 October 2013 92 pages SF COMMENTARY No. 85, October 2013, is edited and published in a limited number of print copies by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough, VIC 3068, Australia. Phone: 61-3-9435 7786. Preferred means of distribution .PDF file from eFanzines.com at: Portrait edition (print equivalent): http://efanzines.com/SFC/SFC85P.PDF or Landscape edition (widescreen): http://efanzines.com/SFC/SFC85L.PDF or from my email address: [email protected]. Front cover: Ditmar (Dick Jenssen): ‘The Alien Race’. Back cover: Steve Stiles: ‘Lovecraft’s Fever Dream’. Artwork Taral Wayne (p. 47); Steve Stiles (p. 52); Brad W. Foster (p. 58). Photographs Peggyann Chevalier (p. 3); Murray and Natalie MacLachlan (p. 4); Helena Binns (p. 26); Barbara Lamar (p. 46); Mervyn and Helena Binns (p. 56); Harold Cazneaux, courtesy Ray Wood (p. 71). 3 I MUST BE TALKING TO MY FRIENDS 45 I MUST BE TALKING TO MY FRIENDS (cond.) 4 Friends lost in 2013 4 The Sea and Summer returns Doug Barbour :: Damien Broderick :: Taral Wayne :: John Litchen :: Michael Bishop :: Yvonne Editor Rousseau :: Kaaron Warren :: Tim Marion :: Steve Sneyd :: George Zebrowski :: 5 FAVOURITES 2012 Franz Rottensteiner :: Paul Anderson :: Favourite books of 2012 Sue Bursztynski :: Martin Morse Wooster :: Favourite novels of 2012 Andy Robson :: Jerry Kaufman :: Rick Kennett Favourite short stories of 2012 :: Lloyd Penney :: Joseph Nicholas :: Casey Wolf :: Murray Moore :: Jeff Hamill :: David Lake :: Favourite films of 2012 Pete Young :: Gary Hoff :: Stephen Campbell :: Favourite films re-seen in 2012 John-Henri Holmberg :: David Boutland Television (?!) 2012 (David Rome) :: Matthew Davis :: Favourite filmed music documentaries 2012 William Breiding :: We Also Heard From .. -

Genre, Iconography and British Legal Film Steve Greenfield University of Westminster School of Law, London, UK

University of Baltimore Law Review Volume 36 Article 6 Issue 3 Spring 2007 2007 Genre, Iconography and British Legal Film Steve Greenfield University of Westminster School of Law, London, UK Guy Osborn University of Westminster School of Law, London, UK Peter Robson University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Greenfield, Steve; Osborn, Guy; and Robson, Peter (2007) "Genre, Iconography and British Legal Film," University of Baltimore Law Review: Vol. 36: Iss. 3, Article 6. Available at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr/vol36/iss3/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Baltimore Law Review by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GENRE, ICONOGRAPHY AND BRITISH LEGAL FILM Steve Greenfieldt Guy Osborntt Peter Robsonttt There is now a huge range of work to be found in the field of law and film. The scholarship varies enormously both in terms of quality and its approach. lOne thing that is marked within the research that has been conducted is the initial centrality of work emanating from the United States. This is undoubtedly a reflection, in part, of the significance of Hollywood, to the global film audience. Historically little attention has been devoted to material produced 'locally', whether within Europe or beyond. -

Human Rights Issues with Change

Page 1 PROUDLY SUPPORTED BY PREMIER PARTNERS COMMUNITY CANDLE PARTNERS Youth for Human Rights Australia MEDIA PARTNERS INDUSTRY PARTNERS DOVE SPONSORS RON GRAY HUMAN RIGHTS FOUNDATION ALAN MISSEN FOUNDATION OLIVE BRANCH SUPPORTERS SPECIALISTS IN CREATING, DESIGNING AND EXECUTING PROMOTIONAL CAMPAIGNS Page 2 Advertising Table of Contents Art 8 Feature films 10-27 Opening Night 13 Timetable 30 Short films 34-42 Closing Night & Awards 38 Action hubs 50 Human rights listings 52 Map 53 Ticketing 55 Page 3 Messages HRAFF Coordinators’ Phillip Noyce Welcome We are thrilled to welcome you to Film and human rights are a dy- Australia’s first ever Human Rights namic combination and film festivals Arts and Film Festival! harness this power. They can’t help but generate new thoughts, new We hope to make human rights connections between people and new accessible, engaging and meaningful to dialogues about human rights. For everyone. Art and film have the power this reason, a festival like the HRAFF to bring us together, remind us of our is long overdue in Australia. humanity and inspire positive change. Don’t be disheartened by what you see From the underbelly of St Kilda to the in these films. Appreciate their beauty. crisis zone of Darfur; from Indonesian Gain strength from the knowledge that art collectives to Sesame Street, our you are part of a society where such a award-winning international and local festival can exist and part of an audi- films and globally renowned artists ence of people who wish to generate explore human rights issues with change. Take part in the discussion tenderness, humour and courage.