Nature, Power, Science and India's Indira Gandhi, 1917-1984

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

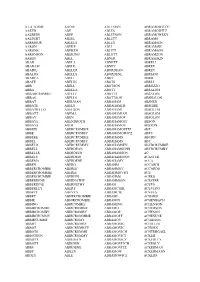

A La Torre Aaker Aalbers Aaldert Aarmour Aaron

A LA TORRE ABDIE ABLEMAN ABRAMOWITCH AAKER ABE ABLES ABRAMOWITZ AALBERS ABEE ABLETSON ABRAMOWSKY AALDERT ABEEL ABLETT ABRAMS AARMOUR ABEELS ABLEY ABRAMSEN AARON ABEKE ABLI ABRAMSKI AARONS ABEKEN ABLITT ABRAMSON AARONSON ABEKING ABLOTT ABRAMZON AASEN ABEL ABNER ABRASHKIN ABAD ABELA ABNETT ABRELL ABADAM ABELE ABNEY ABREU ABADIE ABELER ABORDEAN ABREY ABALOS ABELES ABORDENE ABRIANI ABARCA ABELI ABOT ABRIL ABATE ABELIN ABOTS ABRLI ABB ABELL ABOTSON ABRUZZO ABBA ABELLA ABOTT ABSALOM ABBARCROMBIE ABELLE ABOTTS ABSALON ABBAS ABELLS ABOTTSON ABSHALON ABBAT ABELMAN ABRAHAM ABSHER ABBATE ABELS ABRAHAMER ABSHIRE ABBATIELLO ABELSON ABRAHAMI ABSOLEM ABBATT ABEMA ABRAHAMIAN ABSOLOM ABBAY ABEN ABRAHAMOF ABSOLON ABBAYE ABENDROTH ABRAHAMOFF ABSON ABBAYS ABER ABRAHAMOV ABSTON ABBDIE ABERCROMBIE ABRAHAMOVITZ ABT ABBE ABERCROMBY ABRAHAMOWICZ ABTS ABBEKE ABERCRUMBIE ABRAHAMS ABURN ABBEL ABERCRUMBY ABRAHAMS ABY ABBELD ABERCRUMMY ABRAHAMSEN ABYRCRUMBIE ABBELL ABERDEAN ABRAHAMSOHN ABYRCRUMBY ABBELLS ABERDEEN ABRAHAMSON AC ABBELS ABERDEIN ABRAHAMSSON ACASTER ABBEMA ABERDENE ABRAHAMY ACCA ABBEN ABERG ABRAHM ACCARDI ABBERCROMBIE ABERLE ABRAHMOV ACCARDO ABBERCROMMIE ABERLI ABRAHMOVICI ACE ABBERCRUMBIE ABERLIN ABRAHMS ACERO ABBERDENE ABERNATHY ABRAHMSON ACESTER ABBERDINE ABERNETHY ABRAM ACETO ABBERLEY ABERT ABRAMCHIK ACEVEDO ABBETT ABEYTA ABRAMCIK ACEVES ABBEY ABHERCROMBIE ABRAMI ACHARD ABBIE ABHIRCROMBIE ABRAMIN ACHENBACH ABBING ABIRCOMBIE ABRAMINO ACHENSON ABBIRCROMBIE ABIRCROMBIE ABRAMO ACHERSON ABBIRCROMBY ABIRCROMBY ABRAMOF ACHESON ABBIRCRUMMY ABIRCROMMBIE ABRAMOFF -

Kumon's Recommended Reading List

KUMON’S RECOMMENDED READING LIST - Level 7A ~ Level 3A These are read-aloud books to be used by a parent when reading to the student. LEVEL 7A LEVEL 6A LEVEL 5A LEVEL 4A LEVEL 3A Barnyard Banter Hop on Pop Mean Soup Henny Penny A My Name is Alice 1 Denise Fleming 1 Dr. Seuss 1 Betsy Everitt 1 retold by Paul Galdone 1 Jane Bayer Jesse Bear, What Will Each Orange Had Eight Each Peach Pear Plum The Doorbell Rang Alphabears: An ABC Book 2 You Wear? Slices: A Counting Book Janet and Allen Ahlberg 2 2 Pat Hutchins 2 Kathleen Hague 2 Nancy White Carlstrom Paul Giganti Jr. Eating the Alphabet: Fruits What do you do with a Goodnight Moon Bat Jamboree Sea Squares 3 and Vegetables from A to Z kangaroo? Margaret Wise Brown 3 3 3 Kathi Appelt 3 Joy N. Hulme Lois Ehlert Mercer Mayer Here Are My Hands Black? White! Day? Night! The Icky Bug Alphabet Book Curious George Bread and Jam for Frances 4 Bill Martin Jr. and 4 4 4 4 John Archambault Laura Vaccaro Seeger Jerry Pallotta H.A. Rey Russell Hoban I Heard A Little Baa 5 Big Red Barn My Very First Mother Goose Make Way for Ducklings Little Bear Elizabeth MacLeod 5 Margaret Wise Brown 5 edited by Iona Opie 5 Robert McCloskey 5 Else Holmelund Minarik Read Aloud Rhymes for the Noisy Nora A Rainbow of My Own Millions of Cats Lyle, Lyle Crocodile 6 Very Young 6 Rosemary Wells 6 Don Freeman 6 Wanda Gag 6 Bernard Waber collected by Jack Prelutsky Mike Mulligan and His Steam Quick as a Cricket Sheep in a Jeep The Listening Walk Stone Soup 7 Shovel Audrey Wood 7 Nancy Shaw 7 Paul Showers 7 Marcia Brown 7 Virginia Lee Burton Three Little Kittens Silly Sally The Little Red Hen The Three Billy Goats Gruff Ming Lo Moves the Mountain 8 retold by Paul Galdone 8 Audrey Wood 8 retold by Paul Galdone 8 P.C. -

Menagerie Manor, by Gerald Durrell. Hart-Davis, 21S. Those Who Have Been Enchanted by Mr

Book Reviews 61 Zoo Yearbook). The other criticism of this fine production is that the photographs are ludicrously inadequate for the subject. With only eight pages of photographs for 761 pages of text, they can hardly even begin to sum up the visual aspects of the management of captive animals. But it is churlish to comment adversely on these minor points when the author has provided us with such an immensely useful desk volume. No one concerned with the care of wild mammals can afford to be without it. DESMOND MORRIS Menagerie Manor, by Gerald Durrell. Hart-Davis, 21s. Those who have been enchanted by Mr. DurrelPs previous animal books will not be disappointed by this one describing the first five years of the Jersey Zoo at Les Augres Manor. It consists of a series of delightfully told anecdotes about the inmates of a very happy zoo. Visiting there last summer I was immediately impressed by the tameness and general well- being of the animals, due, I am certain to the pains which Mr. Durrell and his staff take to get to know each one as an individual; they all recognised and greeted him with unmistakable affection when he passed by. The author is conservation-minded, and he describes the dilemma of the zoo director faced with the offer from a dealer of a young orang-utan. Should he refuse it on the grounds that to accept is to stimulate further demand ? Or should he accept because his zoo offers the best chance of survival for this particular animal ? Until the zoos and conservation authorities have this question worked out and until the recent legislation controlling the import of rare animals in this country becomes effective, the zoo director must be guided by his conscience and balance his altruism against his acquisitive enthusiasm. -

Abernathy, Adams, Addison, Alewine, Allen, Allred

BUSCAPRONTA www.buscapronta.com ARQUIVO 14 DE PESQUISAS GENEALÓGICAS 168 PÁGINAS – MÉDIA DE 54.100 SOBRENOMES/OCORRÊNCIA Para pesquisar, utilize a ferramenta EDITAR/LOCALIZAR do WORD. A cada vez que você clicar ENTER e aparecer o sobrenome pesquisado GRIFADO (FUNDO PRETO) corresponderá um endereço Internet correspondente que foi pesquisado por nossa equipe. Ao solicitar seus endereços de acesso Internet, informe o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO, o número do ARQUIVO BUSCAPRONTA DIV ou BUSCAPRONTA GEN correspondente e o número de vezes em que encontrou o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO. Número eventualmente existente à direita do sobrenome (e na mesma linha) indica número de pessoas com aquele sobrenome cujas informações genealógicas são apresentadas. O valor de cada endereço Internet solicitado está em nosso site www.buscapronta.com . Para dados especificamente de registros gerais pesquise nos arquivos BUSCAPRONTA DIV. ATENÇÃO: Quando pesquisar em nossos arquivos, ao digitar o sobrenome procurado, faça- o, sempre que julgar necessário, COM E SEM os acentos agudo, grave, circunflexo, crase, til e trema. Sobrenomes com (ç) cedilha, digite também somente com (c) ou com dois esses (ss). Sobrenomes com dois esses (ss), digite com somente um esse (s) e com (ç). (ZZ) digite, também (Z) e vice-versa. (LL) digite, também (L) e vice-versa. Van Wolfgang – pesquise Wolfgang (faça o mesmo com outros complementos: Van der, De la etc) Sobrenomes compostos ( Mendes Caldeira) pesquise separadamente: MENDES e depois CALDEIRA. Tendo dificuldade com caracter Ø HAMMERSHØY – pesquise HAMMERSH HØJBJERG – pesquise JBJERG BUSCAPRONTA não reproduz dados genealógicos das pessoas, sendo necessário acessar os documentos Internet correspondentes para obter tais dados e informações. DESEJAMOS PLENO SUCESSO EM SUA PESQUISA. -

Dance, INSTITUTION N.North

bio O 4 DOCUUENT anums 0 ED 141 757 12 00565 '.. ,/ TITLE -::,Advisory List of Instructional Media for dance, INSTITUTION N.North. Carolina-a- Dept. cf 'Public Ins ruction; Ral4igh. Div. of,Educational Media. , , ( PUB DNrDATE :77 . :" NOTE, 87p.; For related docim ents, see.IR 065'550-569 - .EDRS-PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$4.67 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Annotated Bibliographies; *Book Reviews; Elementary Grades ;' *Instructional Media; *Library Collebtions; Primary Grades; School Libraries; *Science Education; *Science Programs; Seccndary Grades ABSTRACT . \ This advisdry list deiciibes instructional media , appropriate to school science programs' for primary through tsenior high school grade levels. Entries included on the list were selected from those materials submitted by publishers which received favorable reviews by educators. Materials are arranged by type of media: books, films,filmstrips, kits, slide sets, and study prints. An unannotated list of books favorably reviewed in the indicated sources is / attacked. Entries include citation, price if available,grade-Avel, and annotation. (Authoi/KP) N . **W****************************************************************** '* * . Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made - * * from the original document. ************************************************i********************** OF HEALTH. U S DEPARTMENT EDUCATION &WELFARE NAtIONAL INSTITUTE OF DUCATION HAS BEEN REPRO- THIS DOCIJMENTAS ReCEIVED FROM DUCED EXACTLYORGANIZATION ORIGIN- THE PERSON OR viEW OR OPINIONS ATING IT POINTS OF NECESSARILY REPRE- STATED DO NOT OF NATIONAL (POLICY SENT OFFICIALPOSMON OR POLICY , EDUCATION 4K ss N a 7. ADVISORY LIST OF INSTRUCTIONAL MEDIA FOR SCIENCE "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS 1 MAE.RIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY 7 Rita* G. Graves , TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOVRCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) AND USERS OF THE.ERIC SYSTEM " r State Department of Public Instruction Division of educational media Raleigb,,%North Carolina Jan. -

Gerald Durrell)

BIBLIOTECA TECLA SALA April 20, 2017 My Family And Other Animals (Gerald Durrell) The world is as delicate and as complicated as a spider’s web. If you touch one thread you send shudders running through all the other threads. We are not just touching the web we are Contents: tearing great holes in it. Gerald Durrell - A 2 Brief Biography My Family And Other 3 Gerald Durrell Animals - About [https://www.durrell.org/about/gerald-durrell/gerald- A Triumph Of 4-7 durrell/] Conscious Craft Notes 8 Page 2 Gerald Durrell - A Brief Biography Gerald Durrell was born in Encouraged by Lawrence, he aged 70. He left an indelible Jamshedpur, India, on 7th began writing stories of his mark on the conservation January 1925. Following the animal escapades for magazi- world and a valuable legacy death of his father in 1928 the nes and radio broadcasts, for future generations. family moved back to the UK, publishing his first book, The Gerry’s mission and vision but spurred on by Gerald’s Overloaded Ark, in 1953. He continue through the tireless oldest brother, Lawrence, eventually wrote 33 books, work of Durrell’s dedicated they soon returned to a war- including the best-selling The conservationists throughout mer climate, this time the Bafut Beagles, A Zoo in My the world. island of Corfu. Luggage, Catch Me a Colobus, The Stationary Ark, The Ark’s Here Gerald Durrell’s in- Anniversary and, his final book, [https://www.durrell.org/ terest in animals and all things The Aye-aye and I, published in about/gerald-durrell/gerald- living blossomed, fuelled by a 1992. -

Caribbean Women in Science and Their Careers

CARIBBEAN WOMEN IN SCIENCE AND THEIR CAREERS Author: NIHERST Publisher: NIHERST Editors: Christiane Francois, Joycelyn Lee Young and Trinity Belgrave Researchers/Writers: Stacey-Ann Sarjusingh, Sasha James, Keironne Banfield-Nathaniel and Alana Xavier Design/Layout: Justin Joseph and Phoenix Productions Ltd Print: Scrip J Some of the photographs and material used in this publication were obtained from the Internet, other published documents, featured scientists and their institutions. This publication is NOT FOR SALE. Copyright August 2011 by NIHERST All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means or stored in a database or retrieval system without prior written permission of NIHERST. For further information contact: NIHERST 43-45 Woodford Street, Newtown, Port-of-Spain E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.niherst.gov.tt Telephone: 868-622-7880 Fax: 868-622-1589 ISBN 978-976-95273-6-2 Funding: Ministry of Science, Technology & Tertiary Education, Trinidad and Tobago Foreword Acknowledgements List of Abbreviations Camille Wardrop Alleyne Aerospace Engineer 6 Zulaika Ali Neonatologist 48 Frances Chandler Agronomist 8 Nita Barrow Nurse 50 Hilary Ann Robotham Westmeier Analytical Chemist 10 Susan Walker Nutritionist 52 Camille Selvon Abrahams Animator 12 Anesa Ahamad Oncologist 54 Shirin Haque Astronomer 14 Celia Christie-Samuels Paediatrician 56 Dolly Nicholas Chemist 16 Kathleen Coard Pathologist 58 Patricia Carrillo Construction Manager 18 Merle Henry Pharmacist 60 Rosalie -

The Charlotte Zolotow Award Observations About Publishing in 1998

CCBC Choices Kathleen T. Horning Ginny Moore Kruse Megan Schliesman Cooperative Children's Book Center School of Education University of Wisconsin-Madison Copyright 01999, Friends of the CCBC, Inc. (ISBN 0-931641-98-5) CCBC Choices was produced by University Publications, University of Wisconsin-Madison. Cover design: Lois Ehlert For information about other CCBC publications, send a self- addressed, stamped envelope to: Cooperative Children's Book Cenrer, 4290 Helen C. White Hall, School of Education, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 600 N. Park St., Madison, WI 53706-1403 USA. Inquiries may also be made via fax (6081262-4933) or e-mail ([email protected]).See the World Wide Web (http://www.soemadison.wisc.edu/ccbc/)for information about CCBC publications and the Cooperative Children's Book Center. Contents Acknowledgments Introduction Results of the CCBC Award Discussions The Charlotte Zolotow Award Observations about Publishing in 1998 The Choices The Natural World Seasons and Celebrations Folklore, Mythology and Traditional Literature Historical People, Places and Events Biography 1 Autobiography Contemporary People, Places and Events Issues in Today's World Understanding Oneself and Others The Arts Poetry Concept Books Board Books Picture Books for Younger Children Picture Books for Older Children Easy Fiction Fiction for Children Fiction for Teenagers New Editions of Old Favorites Appendices Appendix I: How to Obtain the Books in CCBC Choices and CCBC Publications Appendix 11: The Cooperative Children's Book Center (CCBC) Appendix 111: CCBC Book Discussion Guidelines Appendix IV: The Compilers of CCBC Choices 1998 Appendix V:The Friends of the CCBC, Inc. Index CCBC Choices 1778 5 Acknowledgments Thank you to Friends of the CCBC member Tana Elias for creating the index for this edition of CCBC Choices. -

Guide to the Colin De Land and Pat Hearn Library Collection MSS.012 Hannah Mandel; Collection Processed by Ann Butler, Ryan Evans and Hannah Mandel

CCS Bard Archives Phone: 845.758.7567 Center for Curatorial Studies Fax: 845.758.2442 Bard College Email: [email protected] Annandale-on-Hudson, NY 12504 Guide to the Colin de Land and Pat Hearn Library Collection MSS.012 Hannah Mandel; Collection processed by Ann Butler, Ryan Evans and Hannah Mandel. This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on February 06, 2019 . Describing Archives: A Content Standard Guide to the Colin de Land and Pat Hearn Library Collection MSS.012 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Biographical / Historical ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Scope and Contents ................................................................................................................................................. 6 Arrangement .............................................................................................................................................................. 6 Administrative Information ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Related Materials ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings .................................................................................................................................... -

Gerald Durrell

Gerald Durrell. Gerald Malcolm Durrell, OBE was a British naturalist, Durrell’s childhood was an unusual one. Following the death zookeeper, conservationist, author, and television of his father his mother decided to move the family, which presenter. He was born in1925, in India and died in 1995 consisted of herself, Gerald, his older sister Margo and his in Jersey. older brothers Lesley and Larry, away from Bournemouth to the Greek island of Corfu. She hoped to find a more affordable lifestyle, a warmer climate and wanted her children to find happiness. In Corfu Gerald had the freedom to explore and spent his days studying animals, insects and birds. He quickly became passionate about the need for humans to understand, Gerald Durrell was the first person to say that zoos respect and preserve all living creatures. Gerald’s family has should focus on the preservation of endangered often been described as eccentric and they hosted many species. He believed that in a zoo the animals creative, artistic and entertaining people when they opened came first and the paying public second. their home as a guesthouse in order to make money. He founded the Durrell Wildlife Conservation As an adult Gerald initially struggled to find the money to Trust and the Jersey Zoo on the Channel Island of pay for the land for his zoo, but his family encouraged him to raise the money through writing. His best loved and most Jersey in 1959. This organisation has become the famous books are a trilogy about his time in Corfu. The centre of expertise of breeding endangered books were an instant hit and provided an income to species and their current aim is to breed and then support the development of the zoo in Jersey and eventually ‘re-wild’ endangered species. -

Gerald Durrell 1 Gerald Durrell

Gerald Durrell 1 Gerald Durrell Gerald M. Durrell Born 7 January 1925 Jamshedpur, India Died 30 January 1995 (aged 70) Saint Helier, Jersey Cause of death Septicaemia Known for Founder of Jersey Zoo, author, television presenter, conservationist Spouse(s) Jacquie Durrell (married 1951-1979), Lee Durrell (married 1979) Parents Lawrence Samuel Durrell and Louisa Dixie Durrell Family Lawrence (brother), Margaret (sister), Leslie (brother) Gerald "Gerry" Malcolm Durrell, OBE (7 January 1925 – 30 January 1995) was an English naturalist, zookeeper, conservationist, author and television presenter. He founded what is now called the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust and the Jersey Zoo (now Durrell Wildlife Park) on the Channel Island of Jersey in 1958, but is perhaps best remembered for writing a number of books based on his life as an animal collector and enthusiast. He was the youngest brother of the novelist Lawrence Durrell. Early life and education Durrell was born in Jamshedpur, India on 7 January 1925. He was the fourth surviving and final child of Louisa Florence Dixie and Lawrence Samuel Durrell, both of whom were born in India of English and Irish descent. Durrell's father was a British engineer and as was commonplace and befitting family status, the infant Durrell spent most of his time in the company of an ayah (nursemaid). Durrell reportedly recalled his first visit to a zoo in India and attributed his lifelong love of animals to that encounter. The family moved to England after the death of his father in 1928 and settled in the Upper Norwood - Crystal Palace area of South London. -

THE MYTHOPOESIS of LAWRENCE DURRELL by PHYLLIS MARGERY

THE MYTHOPOESIS OF LAWRENCE DURRELL by PHYLLIS MARGERY REEVE B.A., Bishop's University, 1958 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of English We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1965 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study* I further agree that per• mission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publi- cation of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission* Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada D ^e ^UJ/ £QT ff^S ii ABSTRACT In The Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durrell develops a series of images involving mirrors, to suggest that truth, especially the truth about oneself, is to be approached only through the juxtaposi• tion of many memories, times and selves. Since the self must find itself through other selves, the artist is concerned with love and friendship, where self is revealed in its relation to the other. In narcissism and incest, the self becomes the other, in relation to its own divided being. The use of mirror allusions in connection with the acquisi• tion of self-knowledge is apparent not only in the Quartet, but also in Durrell1s poetry and in the early novels The Black Book and The Dark Labyrinth.