Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Re-Read the Passage of Scripture Matthew 1:1-17 the Book of The

Re-read the passage of Scripture Matthew 1:1-17 The book of the genealogy of Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham. 2 Abraham was the father of Isaac, and Isaac the father of Jacob, and Jacob the father of Judah and his brothers, 3 and Judah the father of Perez and Zerah by Tamar, and Perez the father of Hezron, and Hezron the father of Ram, 4 and Ram the father of Amminadab, and Amminadab the father of Nahshon, and Nahshon the father of Salmon, 5 and Salmon the father of Boaz by Rahab, and Boaz the father of Obed by Ruth, and Obed the father of Jesse, 6 and Jesse the father of David the king. And David was the father of Solomon by the wife of Uriah, 7 and Solomon the father of Rehoboam, and Rehoboam the father of Abijah, and Abijah the father of Asaph, 8 and Asaph the father of Jehoshaphat, and Jehoshaphat the father of Joram, and Joram the father of Uzziah, 9 and Uzziah the father of Jotham, and Jotham the father of Ahaz, and Ahaz the father of Hezekiah, 10 and Hezekiah the father of Manasseh, and Manasseh the father of Amos, and Amos the father of Josiah, 11 and Josiah the father of Jechoniah and his brothers, at the time of the deportation to Babylon. 12 And after the deportation to Babylon: Jechoniah was the father of Shealtiel, and Shealtiel the father of Zerubbabel, 13 and Zerubbabel the father of Abiud, and Abiud the father of Eliakim, and Eliakim the father of Azor, 14 and Azor the father of Zadok, and Zadok the father of Achim, and Achim the father of Eliud, 15 and Eliud the father of Eleazar, and Eleazar the father of Matthan, and Matthan the father of Jacob, 16 and Jacob the father of Joseph the husband of Mary, of whom Jesus was born, who is called Christ. -

Arguing Their World: the Representation of Major Social and Cultural Issues in Edna Ferber’S and Fannie Hurst’S Fiction, 1910-1935

1 ARGUING THEIR WORLD: THE REPRESENTATION OF MAJOR SOCIAL AND CULTURAL ISSUES IN EDNA FERBER’S AND FANNIE HURST’S FICTION, 1910-1935 A dissertation presented By Kathryn Ruth Bloom to The Department of English In partial fulfillment of the reQuirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the field of English Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts April 2018 2 ARGUING THEIR WORLD: THE REPRESENTATION OF MAJOR SOCIAL AND CULTURAL ISSUES IN EDNA FERBER’S AND FANNIE HURST’S FICTION, 1910-1935 A dissertation presented By Kathryn Ruth Bloom ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the reQuirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University April 2018 3 ABSTRACT BetWeen the early decades of the twentieth-century and mid-century, Edna Ferber and Fannie Hurst were popular and prolific authors of fiction about American society and culture. Almost a century ago, they were writing about race, immigration, economic disparity, drug addiction, and other issues our society is dealing with today with a reneWed sense of urgency. In spite of their extraordinary popularity, by the time they died within a feW months of each other in 1968, their reputations had fallen into eclipse. This dissertation focuses on Ferber’s and Hurst’s fiction published betWeen approximately 1910 and 1935, the years in Which both authors enjoyed the highest critical and popular esteem. Perhaps because these realistic narratives generally do not engage in the stylistic experimentation of the literary world around them, literary scholars came to undervalue their Work. -

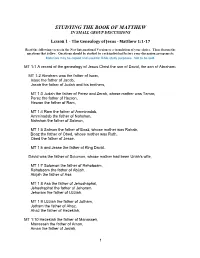

Studying the Book of Matthew in Small Group Discussions

STUDYING THE BOOK OF MATTHEW IN SMALL GROUP DISCUSSIONS Lesson 1 - The Genealogy of Jesus - Matthew 1:1-17 Read the following verses in the New International Version or a translation of your choice. Then discuss the questions that follow. Questions should be studied by each individual before your discussion group meets. Materials may be copied and used for Bible study purposes. Not to be sold. MT 1:1 A record of the genealogy of Jesus Christ the son of David, the son of Abraham: MT 1:2 Abraham was the father of Isaac, Isaac the father of Jacob, Jacob the father of Judah and his brothers, MT 1:3 Judah the father of Perez and Zerah, whose mother was Tamar, Perez the father of Hezron, Hezron the father of Ram, MT 1:4 Ram the father of Amminadab, Amminadab the father of Nahshon, Nahshon the father of Salmon, MT 1:5 Salmon the father of Boaz, whose mother was Rahab, Boaz the father of Obed, whose mother was Ruth, Obed the father of Jesse, MT 1:6 and Jesse the father of King David. David was the father of Solomon, whose mother had been Uriah's wife, MT 1:7 Solomon the father of Rehoboam, Rehoboam the father of Abijah, Abijah the father of Asa, MT 1:8 Asa the father of Jehoshaphat, Jehoshaphat the father of Jehoram, Jehoram the father of Uzziah, MT 1:9 Uzziah the father of Jotham, Jotham the father of Ahaz, Ahaz the father of Hezekiah, MT 1:10 Hezekiah the father of Manasseh, Manasseh the father of Amon, Amon the father of Josiah, 1 MT 1:11 and Josiah the father of Jeconiah* and his brothers at the time of the exile to Babylon. -

Books Owned by F Scott Fitzgerald

Books owned by F. Scott Fitzgerald 1. Aces; A collection of short stories. New York, G.P. Putnam sons, 1924. FSF$$ (Ex)3740.8.3267 2. Adams, Franklin P., and Harry Hansen. Answer This One : Questions for Everybody. New York: Edward J. Clode, 1927. Call Number: Rare Books (Ex) 4294.114 Notes: compiled by Franklin P. Adams (F. P. A.) and Harry Hansen. Romance and chivalry -- The 'nineties -- Music -- Books and authors -- Gilbert and Sullivan -- Popular songs since 1900 -- How long is your memory? -- Golf -- Pugilism -- In little old New York -- Familiar misquotations -- Bible -- Answers -- Lorelei's questionnaire. F. Scott Fitzgerald's copy. Markings and notations. 3. Aeschylus, and E. D. A. Morshead. The House of Atreus; Being the Agamemnon, Libation-Bearers, and Æschylus. Golden Treasury Series. London, Macmillan, 1911. Call Number: Rare Books (Ex) 2559.319.911 Notes: Tr. into English verse by E.D.A. Morshead ... F. Scott Fitzgerald's copy. "First edition 1901. Reprinted 1904, 1911." Inscribed by FSF on front flyleaf. 4. Allen, Frederick Lewis. Only Yesterday; an Informal History of the Nineteen-Twenties. New York, London, Harper & brothers, 1931. Rare Books (Ex) 1088.1195.2 Notes: by Frederick Lewis Allen. "Second printing." "Sources and obligations": p. 358-361. Copy 2-5 Imprint varies. Cop. 4. imperfect. 2 . wanting. 21 cm. Ex copy is "Twenty-ninth printing." [1931]. F. Scott Fitzgerald's copy with his ms. annotations. Notation on front flyleaf: “Pps 11, 90, 91, 226, 234 [referring to mention or quotation of FSF.]” 5. Anderson, Margaret My thirty years’ war; An autobiography. New York, Covici, Friede, 1930. -

Hebrew Names and Name Authority in Library Catalogs by Daniel D

Hebrew Names and Name Authority in Library Catalogs by Daniel D. Stuhlman BHL, BA, MS LS, MHL In support of the Doctor of Hebrew Literature degree Jewish University of America Skokie, IL 2004 Page 1 Abstract Hebrew Names and Name Authority in Library Catalogs By Daniel D. Stuhlman, BA, BHL, MS LS, MHL Because of the differences in alphabets, entering Hebrew names and words in English works has always been a challenge. The Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) is the source for many names both in American, Jewish and European society. This work examines given names, starting with theophoric names in the Bible, then continues with other names from the Bible and contemporary sources. The list of theophoric names is comprehensive. The other names are chosen from library catalogs and the personal records of the author. Hebrew names present challenges because of the variety of pronunciations. The same name is transliterated differently for a writer in Yiddish and Hebrew, but Yiddish names are not covered in this document. Family names are included only as they relate to the study of given names. One chapter deals with why Jacob and Joseph start with “J.” Transliteration tables from many sources are included for comparison purposes. Because parents may give any name they desire, there can be no absolute rules for using Hebrew names in English (or Latin character) library catalogs. When the cataloger can not find the Latin letter version of a name that the author prefers, the cataloger uses the rules for systematic Romanization. Through the use of rules and the understanding of the history of orthography, a library research can find the materials needed. -

The Family History: the First Genetic Test, and Still Useful After All Those Years?

©American College of Medical Genetics REVIEW The family history: the first genetic test, and still useful after all those years? Reed E. Pyeritz, MD, PhD1 The family history has its origins in genealogy and over the past family history, without a clearer sense of clinical validity and utility, its century has become embedded in clinical practice. Its importance role will likely diminish. The time to perform the requisite investiga- in specialized circumstances is unquestioned but largely untested. tions is now. Moreover, the relevance of the family history to common diseases, especially in an era of genomic markers that convey risk and the Genet Med 2012:14(1):3–9 emphasis on “personalized medicine,” must be given careful scru- Key Words: tiny. Given the time and expertise needed to obtain and interpret the clinical utility; family history; genealogy; genetic testing “Abraham was the father of Isaac, Isaac the father of healthy females.4 He documented how the family itself learned to Jacob, Jacob the father of Judah and his brothers, Judah avoid a common treatment of a variety of ailments. “So assured the father of Perez and Zerah, whose mother was Tamar, are the members of this family of the terrible consequences of Perez the father of Hezron, Hezron the father of Ram, the least wound, that they will not suffer themselves to be bled Ram the father of Amminadab, Amminadab the father on any consideration, having lost a relation by not being able to of Nahshon, Nahshon the father of Salmon, Salmon the stop the discharge occasioned by this operation.” Ten years later, father of Boaz, whose mother was Rahab, Boaz the father Hay added the observation that unaffected daughters of affected of Obed, whose mother was Ruth, Obed the father of Jesse, males could themselves bear affected sons.5 This information and Jesse the father of King David. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Black Mexico's Sites of Struggles Across Borders

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Black Mexico’s Sites of Struggles across Borders: The Problem of the Color Line A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Hispanic Languages and Literatures by Christian Yanaí Bermúdez-Castro 2018 © Copyright by Christian Yanaí Bermúdez-Castro 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Black Mexico’s Sites of Struggles across Borders: The Problem of The Color Line by Christian Yanaí Bermúdez-Castro Doctor of Philosophy in Hispanic Languages and Literatures University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Héctor V. Calderón, Chair This dissertation studies the socio-cultural connections of the United States and Mexico’s Pan-African selected twentieth- and twenty-first century sites of struggle through literature, film, and music. Novels and movies such as La negra Angustias (1948/1950), Imitation of Life (1933/1959), Angelitos negros (1948/1970), Como agua para chocolate saga (1989, 2016, 2017), and film (1992), as well as music of racial activism by Mexican and Afro-Latino artists such as Negro José and Afro-Chicano band Third Root, are all key elements of my project to study the formation and understanding what of Mexico’s Tercera Raíz entails historically, politically, and culturally. I focus my study on the development of black racial consciousness in twentieth-century Mexican cultural life, and I consequently explore the manner in which Mexican writers, filmmakers and artists have managed the relationship between Afro-Mexicans and majority ii populations of white and mestizo Mexicans, as well as the racial bridge existent between the United States’ black history, and Mexico’s Third Root. -

It the Whatever

Cinderella Revived She Also Serves Entertainment ‘The Last Gangster” 1 Legend Plentiful \t the Columbia. pULL of prison mclodramatics and I Next Week Beginning * In Crawford Film In Hotel” tough yeggs, "The Last Gangster” Monday Night “Hollywood low has moved down to the Columbia ^GEORGE ABBOTT’S ;o take up again its P street run. Prin- “Mannequin” at Palace Shows Joan New Dick Powell Musical :ipally notable for his characteriza- Brings tion, "The Last Gangster” presents In Role She Portrays Best. Much to Mr. Edward G. Robinson as the Ed- Gayety the Earle. ward G. Robinson gunman to end all 463 LAUGHS Edward G. Robinson Spencer Tracy Excellent. Baker on gunmen, which Seats Benny Stage. probably would be a good idea no mat- Now! New Prices! By JAY CARMODY. ter how well Mr. Robinson plays By IIARRY Mac ARTHUR. \ MATINEES Wed., Sat., 50c to $1.50 gangster roles. There is no denying, I Cinderella legend which she has lived, unless her biographers have Brothers Warner have been lavish unto with the enter- prodigality of course, that it is the sort of thing I done her wrong, has been revived for Joan Crawford's picture, “Manne- tainment with which they have endowed TOMORROW NIGHT AT Hollywood Hotel,” the new he does to perfection and at which he 8:30 which at the Palace. It not be the fllmusical quin,” opened yesterday may at the Earle. There is sufficient here for at least two ONE PERFORMANCE ONLY has no peers, so it is a satisfying ex- THEpicture which Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer has been to restore Miss musicals and one seeking THE slap-happy romantic comedy, with left over to find President's Birthday Committee enough perience him just once more Crawford to her old This for a A unounces box-offlcc standing. -

Luke Reading #8

Luke Week Eight Bible Reading Notes 1. Take a few minutes to catch up and pray that God would bless you through the reading of His word. 2. Read Luke 3:23-38 [3:23] Jesus, when he began his ministry, was about thirty years of age, being the son (as was supposed) of Joseph, the son of Heli, [24] the son of Matthat, the son of Levi, the son of Melchi, the son of Jannai, the son of Joseph, [25] the son of Mattathias, the son of Amos, the son of Nahum, the son of Esli, the son of Naggai, [26] the son of Maath, the son of Mattathias, the son of Semein, the son of Josech, the son of Joda, [27] the son of Joanan, the son of Rhesa, the son of Zerubbabel, the son of Shealtiel, the son of Neri, [28] the son of Melchi, the son of Addi, the son of Cosam, the son of Elmadam, the son of Er, [29] the son of Joshua, the son of Eliezer, the son of Jorim, the son of Matthat, the son of Levi, [30] the son of Simeon, the son of Judah, the son of Joseph, the son of Jonam, the son of Eliakim, [31] the son of Melea, the son of Menna, the son of Mattatha, the son of Nathan, the son of David, [32] the son of Jesse, the son of Obed, the son of Boaz, the son of Sala, the son of Nahshon, [33] the son of Amminadab, the son of Admin, the son of Arni, the son of Hezron, the son of Perez, the son of Judah, [34] the son of Jacob, the son of Isaac, the son of Abraham, the son of Terah, the son of Nahor, [35] the son of Serug, the son of Reu, the son of Peleg, the son of Eber, the son of Shelah, [36] the son of Cainan, the son of Arphaxad, the son of Shem, the son of Noah, the son of Lamech, [37] the son of Methuselah, the son of Enoch, the son of Jared, the son of Mahalaleel, the son of Cainan, [38] the son of Enos, the son of Seth, the son of Adam, the son of God. -

Zora Neale Hurston Daryl Cumber Dance University of Richmond, [email protected]

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository English Faculty Publications English 1983 Zora Neale Hurston Daryl Cumber Dance University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/english-faculty-publications Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Literature Commons, Caribbean Languages and Societies Commons, Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Dance, Daryl Cumber. "Zora Neale Hurston." In American Women Writers: Bibliographical Essays, edited by Maurice Duke, Jackson R. Bryer, and M. Thomas Inge, 321-51. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1983. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the English at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 12 DARYL C. DANCE Zora Neale Hurston She was flamboyant and yet vulnerable, self-centered and yet kind, a Republican conservative and yet an early black nationalist. Robert Hemenway, Zora Neale Hurston. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1977 There is certainly no more controversial figure in American literature than Zora Neale Hurston. Even the most common details, easily ascertainable for most people, have been variously interpreted or have remained un resolved issues in her case: When was she born? Was her name spelled Neal, Neale, or Neil? Whom did she marry? How many times was she married? What happened to her after she wrote Seraph on the Suwanee? Even so immediately observable a physical quality as her complexion sparks con troversy, as is illustrated by Mary Helen Washington in "Zora Neale Hurston: A Woman Half in Shadow," Introduction to I Love Myself When I Am Laughing . -

The Other Side of Willa Cather

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: The Other Side of Willa Cather Full Citation: Marilyn Arnold, “The Other Side of Willa Cather,” Nebraska History 68 (1987): 74-82 URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1987WCather.pdf Date: 10/18/2013 Article Summary: Cather biographies emphasize that she was often difficult and inaccessible. Her personal friends and many who knew her casually remembered her more positively. Cataloging Information: Cather Biographers: John H Randall III, Paul Horgan, E K Brown, James Woodress, Mildred R Bennett, L K Ingersoll, Marion Marsh Brown, Ruth Crone, Elizabeth Moorhead Vermorcken Cather Acquaintances: Alfred A Knopf, Edith Lewis, Elizabeth Sergeant, George Seibel, Fanny Butcher, Elmer Alonzo Thomas, Phyllis Martin Hutchinson, Fannie Hurst, Lorna R F Birtwell, Frank Swinnerton, Marion King, Truman Capote, Mary Ellen Chase, Evaline Rolofson, Eleanor -

The Internal Consistency and Historical Reliability of the Biblical Genealogies

Vetus Testamentum XL, 2 (1990) THE INTERNAL CONSISTENCY AND HISTORICAL RELIABILITY OF THE BIBLICAL GENEALOGIES by GARY A. RENDSBURG Ithaca, New York The general trend among scholars in recent years has been to treat the genealogies recorded in the Bible with an increased skep- ticism. Whereas past generations of scholars may have been ready to affirm the trustworthiness of at least some of the Israelite lineages, current research in this area has led to the opposite con- clusion. Provided with parallels both from ancient Near Eastern documents and from the sociological and anthropological study of tribal societies of the present, most scholars today contend that the biblical genealogies do not constitute a reliable source for the reconstruction of history.' The current approach is that the genealogies may retain some value for the reconstruction of political ties on a national or tribal level,2 but that in no way should they be taken at face value. This is especially true for those genealogies which purport to be from early Israelite times, such as the lineages of Moses or David. In the present article I will offer some evidence which, depending on how it is judged, may stem the tide described above. The approach to be taken will differ from recent work on the subject, in that it will adduce no external evidence from either ancient or modern times. Instead, I will concentrate on the genealogies them- selves, in particular those lineages of characters who appear in Exodus through Joshua. I anticipate one of the results of my analysis with the following statement: the genealogies themselves 1 See especially R.