Mohr Siebeck an Aramaic Amulet for Winning a Case in a Court of Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Azharos-Piyuttim Unique to Shavuos

dltzd z` oiadl Vol. 10 No. 17 Supplement b"ryz zereay zexdf`-miheit Unique To zereay The form of heit known as dxdf` is recited only on the holiday of 1zereay. An dxdf` literary means: a warning. As a form of heit, an dxdf` represents a poem in which the author weaves into the lines of the poem references to each of the zeevn b"ixz. Why did this form of heit become associated with the holiday of zereay? Is there a link between the zexdf` and the zexacd zxyr? To answer that question, we need to ask some additional questions. Should we be reciting the zexacd zxyr as part of our zelitz each day and why do we not? In truth, we should be reciting the zexacd zxyr as part of our zelitz. Such a recital would represent an affirmation that the dxez was given at ipiq xd and that G-d’s revelation occurred at that time. We already include one other affirmation in our zelitz; i.e. z`ixw rny. The devn of rny z`ixw is performed each day for two reasons; first, because the words in rny z`ixw include a command to recite these words twice each day, jakya jnewae, and second, because the first verse of rny z`ixw contains an affirmation; that G-d is the G-d of Israel and G-d is the one and only G-d. The recital of that line constitutes the Jewish Pledge of Allegiance. Because of that, some mixeciq include an instruction to recite the first weqt of rny z`ixw out loud. -

The Development of the Jewish Prayerbook'

"We Are Bound to Tradition Yet Part of That Tradition Is Change": The Development of the Jewish Prayerbook' Ilana Harlow Indiana University The traditional Jewish liturgy in its diverse manifestations is an imposing artistic structure. But unlike a painting or a symphony it is not the work of one artist or even the product of one period. It is more like a medieval cathedral, in the construction of which many generations had a share and in the ultimate completion of which the traces of diverse tastes and styles may be detected. (Petuchowski 1985:312) This essay explores the dynamics between tradition and innovation, authority and authenticity through a study of a recently edited Jewish prayerbook-a contemporary development in a tradition which can be traced over a one-thousand year period. The many editions of the Jewish prayerbook, or siddur, that have been compiled over the centuries chronicle the contributions specific individuals and communities made to the tradition-informed by the particular fashions and events of their times as well as by extant traditions. The process is well-captured in liturgist Jakob Petuchowski's 'cathedral simile' above-an image which could be applied equally well to many traditions but is most evident in written ones. An examination of a continuously emergent written tradition, such as the siddur, can help highlight kindred processes involved in the non-documented development of oral and behavioral traditions. Presented below are the editorial decisions of a contemporary prayerbook editor, Rabbi Jules Harlow, as a case study of the kinds of issues involved when individuals assume responsibility for the ongoing conserva- tion and construction of traditions for their communities. -

Re-Read the Passage of Scripture Matthew 1:1-17 the Book of The

Re-read the passage of Scripture Matthew 1:1-17 The book of the genealogy of Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham. 2 Abraham was the father of Isaac, and Isaac the father of Jacob, and Jacob the father of Judah and his brothers, 3 and Judah the father of Perez and Zerah by Tamar, and Perez the father of Hezron, and Hezron the father of Ram, 4 and Ram the father of Amminadab, and Amminadab the father of Nahshon, and Nahshon the father of Salmon, 5 and Salmon the father of Boaz by Rahab, and Boaz the father of Obed by Ruth, and Obed the father of Jesse, 6 and Jesse the father of David the king. And David was the father of Solomon by the wife of Uriah, 7 and Solomon the father of Rehoboam, and Rehoboam the father of Abijah, and Abijah the father of Asaph, 8 and Asaph the father of Jehoshaphat, and Jehoshaphat the father of Joram, and Joram the father of Uzziah, 9 and Uzziah the father of Jotham, and Jotham the father of Ahaz, and Ahaz the father of Hezekiah, 10 and Hezekiah the father of Manasseh, and Manasseh the father of Amos, and Amos the father of Josiah, 11 and Josiah the father of Jechoniah and his brothers, at the time of the deportation to Babylon. 12 And after the deportation to Babylon: Jechoniah was the father of Shealtiel, and Shealtiel the father of Zerubbabel, 13 and Zerubbabel the father of Abiud, and Abiud the father of Eliakim, and Eliakim the father of Azor, 14 and Azor the father of Zadok, and Zadok the father of Achim, and Achim the father of Eliud, 15 and Eliud the father of Eleazar, and Eleazar the father of Matthan, and Matthan the father of Jacob, 16 and Jacob the father of Joseph the husband of Mary, of whom Jesus was born, who is called Christ. -

Princeton University Ronald O

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY RONALD O. PERELMAN INSTITUTE FOR JUDAIC STUDIES Program in JUDAIC STUDIES SPRING 2018 RONALD O. PERELMAN INSTITUTE FOR JUDAIC STUDIES I am delighted to have the opportunity to establish this program, which will shape intellectual concepts in the eld, promote interdisciplinary research and scholarship, and perhaps most important, bring Jewish civilization to life for Princeton students— Ronald O. Perelman In 1995 nancier and philanthropist Ronald O. Perelman, well known as an innovative leader and generous supporter of many of the nation’s most prominent cultural and educational institutions, gave Princeton University a gi of $4.7 million to create a multidisciplinary institute focusing on Jewish studies. e establishment of the Ronald O. Perelman Institute for Jewish Studies produced the rst opportunity for undergraduate students to earn a certicate in Jewish Studies, strengthening Princeton’s long tradition of interdisciplinary studies and broad commitment to Jewish culture. e gi from Mr. Perelman, chairman and chief executive ocer of MacAndrews and Forbes Inc., also supports a senior faculty position—the Ronald O. Perelman Professor of Jewish Studies— and a wide variety of academic and scholarly activities that bring together leading scholars to examine Jewish history, religion, literature, thought, society, politics and cultures. FACULTY Executive Committee Leora Batnitzky, Religion Lital Levy, Comparative Literature Yaacob Dweck, History Laura Quick, Religion Jonathan Gribetz, Near Eastern Studies Marina Rustow, Near Eastern Studies Martha Himmelfarb, Religion Esther Schor, English William C. Jordan, History Moulie Vidas, Religion Eve Krakowski, Near Eastern Studies ASSOCIATED FACULTY David Bellos, French and Italian Daniel Heller-Roazen, Comparative Literature Jill S. Dolan, English, Dean of the College Stanley N. -

Melilah Agunah Sptib W Heads

Agunah and the Problem of Authority: Directions for Future Research Bernard S. Jackson Agunah Research Unit Centre for Jewish Studies, University of Manchester [email protected] 1.0 History and Authority 1 2.0 Conditions 7 2.1 Conditions in Practice Documents and Halakhic Restrictions 7 2.2 The Palestinian Tradition on Conditions 8 2.3 The French Proposals of 1907 10 2.4 Modern Proposals for Conditions 12 3.0 Coercion 19 3.1 The Mishnah 19 3.2 The Issues 19 3.3 The talmudic sources 21 3.4 The Gaonim 24 3.5 The Rishonim 28 3.6 Conclusions on coercion of the moredet 34 4.0 Annulment 36 4.1 The talmudic cases 36 4.2 Post-talmudic developments 39 4.3 Annulment in takkanot hakahal 41 4.4 Kiddushe Ta’ut 48 4.5 Takkanot in Israel 56 5.0 Conclusions 57 5.1 Consensus 57 5.2 Other issues regarding sources of law 61 5.3 Interaction of Remedies 65 5.4 Towards a Solution 68 Appendix A: Divorce Procedures in Biblical Times 71 Appendix B: Secular Laws Inhibiting Civil Divorce in the Absence of a Get 72 References (Secondary Literature) 73 1.0 History and Authority 1.1 Not infrequently, the problem of agunah1 (I refer throughout to the victim of a recalcitrant, not a 1 The verb from which the noun agunah derives occurs once in the Hebrew Bible, of the situations of Ruth and Orpah. In Ruth 1:12-13, Naomi tells her widowed daughters-in-law to go home. -

A Comparative Study of Jewish Commentaries and Patristic Literature on the Book of Ruth

A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF JEWISH COMMENTARIES AND PATRISTIC LITERATURE ON THE BOOK OF RUTH by CHAN MAN KI A Dissertation submitted to the University of Pretoria for the degree of PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR Department of Old Testament Studies Faculty of Theology University of Pretoria South Africa Promoter: PIETER M. VENTER JANUARY, 2010 © University of Pretoria Summary Title : A comparative study of Jewish Commentaries and Patristic Literature on the Book of Ruth Researcher : Chan Man Ki Promoter : Pieter M. Venter, D.D. Department : Old Testament Studies Degree :Doctor of Philosophy This dissertation deals with two exegetical traditions, that of the early Jewish and the patristic schools. The research work for this project urges the need to analyze both Jewish and Patristic literature in which specific types of hermeneutics are found. The title of the thesis (“compared study of patristic and Jewish exegesis”) indicates the goal and the scope of this study. These two different hermeneutical approaches from a specific period of time will be compared with each other illustrated by their interpretation of the book of Ruth. The thesis discusses how the process of interpretation was affected by the interpreters’ society in which they lived. This work in turn shows the relationship between the cultural variants of the exegetes and the biblical interpretation. Both methodologies represented by Jewish and patristic exegesis were applicable and social relevant. They maintained the interest of community and fulfilled the need of their generation. Referring to early Jewish exegesis, the interpretations upheld the position of Ruth as a heir of the Davidic dynasty. They advocated the importance of Boaz’s and Ruth’s virtue as a good illustration of morality in Judaism. -

Download Download

New Approaches to Islamic Law and the Documentary Record before 1500 Marina Rustow Princeton University Abstract Marina Rustow notes how prevalent scholarly attention is to long-form texts of Islamic law—attention that she argues, comes at the expense of study- ing Islamic legal documents in a sufficient manner. Study of the documents is an indispensable enterprise if we are to fully understand “how law worked in practice.” In view of what we know to have been “heaps” of documents pro- duced by Muslim judges and notaries, Rustow underscores how particularly noticeable a disjuncture there is between those documents and the long-form texts. Moreover, scholars often skip over and thus fail to avail themselves of the utility of documents in adding texture to social and legal history. She cautions social historians against “pseudo-knowledge,” that is, the tempta- tion to overlook complex factors, usually embedded in legal documents, that render our otherwise tame scholarly perception of the past truer but more “unruly.” In the end, her invitation to join her in the study of documents and thereby improve the state of Islamic legal history is terse and timely: “Please go find yourself some documents.” 179 Journal of Islamic Law | Spring 2021 lthough thousands of Arabic and Persian legal documents survived from the medieval Islamicate world, they still Aappear only rarely in discussions of Islamic law. That’s starting to change, but if we want a well-rounded picture of how law worked in practice, it needs to change faster. Those of us who specialize in documents aren’t interested in hiding them from others. -

Orthodox Divorce in Jewish and Islamic Legal Histories

Every Law Tells a Story: Orthodox Divorce in Jewish and Islamic Legal Histories Lena Salaymeh* I. Defining Wife-Initiated Divorce ................................................................................. 23 II. A Judaic Chronology of Wife-Initiated Divorce .................................................... 24 A. Rabbinic Era (70–620 CE) ............................................................................ 24 B. Geonic Era (620–1050 CE) ........................................................................... 27 C. Era of the Rishonim (1050–1400 CE) ......................................................... 31 III. An Islamic Chronology of Wife-Initiated Divorce ............................................... 34 A. Legal Circles (610–750 CE) ........................................................................... 34 B. Professionalization of Legal Schools (800–1050 CE) ............................... 37 C. Consolidation (1050–1400 CE) ..................................................................... 42 IV. Disenchanting the Orthodox Narratives ................................................................ 44 A. Reevaluating Causal Influence ...................................................................... 47 B. Giving Voice to the Geonim ......................................................................... 50 C. Which Context? ............................................................................................... 52 V. An Interwoven Narrative of Wife-Initiated Divorce ............................................ -

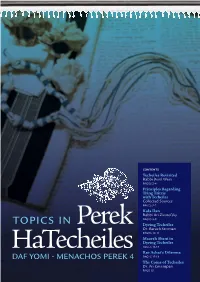

TOPICS in Perek

CONTENTS Techeiles Revisited Rabbi Berel Wein PAGES 2-4 Principles Regarding Tying Tzitzis with Techeiles Collected Sources PAGES 5-7 Kala Ilan Rabbi Ari Zivotofsky PAGES 8-9 TOPICS IN Dyeing Techeiles Perek Dr. Baruch Sterman PAGES 10-11 Maareh Sheni in Dyeing Techeiles PAGES 12-13 HaTecheiles Rav Achai’s Dilemna DAF YOMI • MENACHOS PEREK 4 PAGES 12-13 The Coins of Techeiles Dr. Ari Greenspan PAGE 15 Techeiles Revisited “Color is an emotional Rabbi Berel Wein experience. Techeiles ne of the enduring mysteries of Jewish life following the exile of the is the emotional Jews from the Land of Israel was the disappearance of the string of Otecheiles in the tzitzis garment that Jews wore. Techeiles was known reminder of the bond to be of a blue color while the other strings of the tzitzis were white in color. Not only did Jews stop wearing techeiles but they apparently even forgot how between ourselves and it was once manufactured. The Talmud identified techeiles as being produced Hashem and how we from the “blood” of a sea creature called the chilazon. And though the Talmud did specify certain traits and identifying characteristics belonging to the get closer to Hashem chilazon, the description was never specific enough for later generations of Jews to unequivocally determine which sea creature was in fact the chilazon. with Ahavas Hashem, It was known that the chilazon was harvested in abundance along the northern coast of the Land of Israel from Haifa to south of Tyre in Lebanon (Shabbos the love of Hashem, 26a). Though techeiles itself disappeared from Jewish life as part of the damage the love of Torah and of exile, the subject of techeiles continued to be discussed in the great halachic works of all ages. -

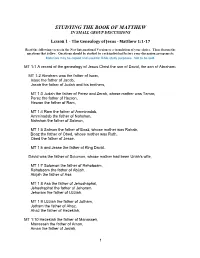

Studying the Book of Matthew in Small Group Discussions

STUDYING THE BOOK OF MATTHEW IN SMALL GROUP DISCUSSIONS Lesson 1 - The Genealogy of Jesus - Matthew 1:1-17 Read the following verses in the New International Version or a translation of your choice. Then discuss the questions that follow. Questions should be studied by each individual before your discussion group meets. Materials may be copied and used for Bible study purposes. Not to be sold. MT 1:1 A record of the genealogy of Jesus Christ the son of David, the son of Abraham: MT 1:2 Abraham was the father of Isaac, Isaac the father of Jacob, Jacob the father of Judah and his brothers, MT 1:3 Judah the father of Perez and Zerah, whose mother was Tamar, Perez the father of Hezron, Hezron the father of Ram, MT 1:4 Ram the father of Amminadab, Amminadab the father of Nahshon, Nahshon the father of Salmon, MT 1:5 Salmon the father of Boaz, whose mother was Rahab, Boaz the father of Obed, whose mother was Ruth, Obed the father of Jesse, MT 1:6 and Jesse the father of King David. David was the father of Solomon, whose mother had been Uriah's wife, MT 1:7 Solomon the father of Rehoboam, Rehoboam the father of Abijah, Abijah the father of Asa, MT 1:8 Asa the father of Jehoshaphat, Jehoshaphat the father of Jehoram, Jehoram the father of Uzziah, MT 1:9 Uzziah the father of Jotham, Jotham the father of Ahaz, Ahaz the father of Hezekiah, MT 1:10 Hezekiah the father of Manasseh, Manasseh the father of Amon, Amon the father of Josiah, 1 MT 1:11 and Josiah the father of Jeconiah* and his brothers at the time of the exile to Babylon. -

The Origins of the 247-Year Calendar Cycle Nadia Vidro

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UCL Discovery The Origins of the 247-year Calendar Cycle Nadia Vidro Aleph: Historical Studies in Science and Judaism, Volume 17, Number 1, 2017, pp. 95-137 (Article) Published by Indiana University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/652312 Access provided by University College London (UCL) (30 Mar 2017 08:39 GMT) Nadia Vidro The Origins of the 247-year Calendar Cycle Many medieval and early modern Jewish calendars were based on the assumption that the calendar repeats itself exactly after 247 years. Although this cycle—known as the ʿIggul of R. Naḥshon Gaon—is discussed in many sources, both medieval and modern, its origins remain a mystery. The present article sheds light on the early history of the reiterative Jewish calendar by looking at the oldest 247-year cycles identified to date. Textsf rom the Cairo Genizah demonstrate that the 247-year cycle originated in Babylonia in the middle of the tenth century and was produced by Josiah b. Mevorakh (ibn) al-ʿĀqūlī, previously known from Judeo-Persian calendar treatises. In contrast, a large body of manuscript evidence shows that the attribution of the cycle to R. Naḥshon Gaon (874–882 CE) is not attested before the twelfth century and may be unhistorical. The 247- year cycle may have been proposed as an alternative Jewish calendar that would eliminate the need for calculation and prevent calendar divergence. But at least from the early twelfth century the cycle was seen as a means of setting the standard calendar, even though it is not fully compatible with the latter. -

Hebrew Names and Name Authority in Library Catalogs by Daniel D

Hebrew Names and Name Authority in Library Catalogs by Daniel D. Stuhlman BHL, BA, MS LS, MHL In support of the Doctor of Hebrew Literature degree Jewish University of America Skokie, IL 2004 Page 1 Abstract Hebrew Names and Name Authority in Library Catalogs By Daniel D. Stuhlman, BA, BHL, MS LS, MHL Because of the differences in alphabets, entering Hebrew names and words in English works has always been a challenge. The Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) is the source for many names both in American, Jewish and European society. This work examines given names, starting with theophoric names in the Bible, then continues with other names from the Bible and contemporary sources. The list of theophoric names is comprehensive. The other names are chosen from library catalogs and the personal records of the author. Hebrew names present challenges because of the variety of pronunciations. The same name is transliterated differently for a writer in Yiddish and Hebrew, but Yiddish names are not covered in this document. Family names are included only as they relate to the study of given names. One chapter deals with why Jacob and Joseph start with “J.” Transliteration tables from many sources are included for comparison purposes. Because parents may give any name they desire, there can be no absolute rules for using Hebrew names in English (or Latin character) library catalogs. When the cataloger can not find the Latin letter version of a name that the author prefers, the cataloger uses the rules for systematic Romanization. Through the use of rules and the understanding of the history of orthography, a library research can find the materials needed.