Conley, James D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Information Series

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Information Series EUGENE KOPP Interviewed by: Tom Tuch Initial interview date: March 7, 1988 Copyright 1998 A ST TABLE OF CONTENTS Coming to USIA Promotion to USIA Assistant Director Administration Sha espeare!s operating policies Policy Differences Strains between USIA and Dept of State Vis a Vis Soviet Union/D'tente Distrust of Foreign Service USIA (eographic Offices Subordinated to Media Offices USIA Deputy Director Corrects policies (eneral Counsel (ordon Strachan a problem Confronting Keogh!s explaining Keogh!s accomplishments Agency difficulties, -atergate VOA director Ken (iddens and Keogh Differences Special Concern .etrospective View Disagreement on Policy between USIA Management and VOA INTERVIEW ": This is Tom Tuch interviewing Eugene Kopp, former Deputy Director of USIA in his office in downtown (ashington, today on March 7, 1988. KOPP/ Tom. 1 ": Nice to see you. KOPP/ Than you very much. Coming to USIA ": Let,s start by tal-ing about your coming into a foreign affairs agency, USIA, from life as a lawyer, during the Ni.on Administration. How did you decide that you wanted to wor- in USIA as a political appointee at that time0 KOPP/ -ell1 let me bac up Tom/ After I got out of law school in 1341 I served a year as law cler for a federal judge1 I then went to the Department of 5ustice in 1342 as a trial attorney. And by 1348 I felt that I probably ought to be thin ing about something else to do because I didn8t thin I wanted to say at 5ustice for a full career. -

Signature Redacted Signature of Author: History, Anthropology, and Science, Technology Affd Society August 19, 2014

Project Apollo, Cold War Diplomacy and the American Framing of Global Interdependence by MASSACHUSETTS 5NS E. OF TECHNOLOGY OCT 0 6 201 Teasel Muir-Harmony LIBRARIES Bachelor of Arts St. John's College, 2004 Master of Arts University of Notre Dame, 2009 Submitted to the Program in Science, Technology, and Society In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, Anthropology, and Science, Technology and Society at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September 2014 D 2014 Teasel Muir-Harmony. All Rights Reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature redacted Signature of Author: History, Anthropology, and Science, Technology affd Society August 19, 2014 Certified by: Signature redacted David A. Mindell Frances and David Dibner Professor of the History of Engineering and Manufacturing Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics Committee Chair redacted Certified by: Signature David Kaiser C01?shausen Professor of the History of Science Director, Program in Science, Technology, and Society Senior Lecturer, Department of Physics Committee Member Signature redacted Certified by: Rosalind Williams Bern Dibner Professor of the History of Technology Committee Member Accepted by: Signature redacted Heather Paxson William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor, Anthropology Director of Graduate Studies, History, Anthropology, and STS Signature -

Interview with Frank S. Ruddy

Library of Congress Interview with Frank S. Ruddy The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR FRANK S. RUDDY Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: September 9, 1991 Copyright 1998 ADST Q: Today is September 9, 1991 and this is an interview with Ambassador Frank S. Ruddy on behalf of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and I am Charles Stuart Kennedy. Mr. Ambassador I wonder if you would give me a little of your background—where were you born, brought up and your education. RUDDY: I was born in New York in 1937 in Jamaica, New York and went to St. Joan of Arc grammar school in Jackson Heights, New York. St Joan's has a number of famous alumni/ae such as John Guare whose play “Six Degrees of Separation” is all the rage on Broadway; Father Tim Healy, the president of Georgetown, and on and on. I went to a Jesuit high school, Xavier, in the city. To New Yorkers “the city” is always Manhattan. I went to college at Holy Cross in Worcester. During that period the Jesuit high schools in the city (there were five of them) would not recommend students or send their transcripts to non-Catholic colleges. (West Point, Annapolis and MIT were exceptions). I completed my military obligation with The Marines (I was discharged with the exalted rank of corporal). After the Marines I got a Master's in English from N.Y.U. and taught English to pay my way through law school. I began teaching in high school and going to law school at night and in the summer and then I got to teach in college. -

![Papers of Clare Boothe Luce [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4480/papers-of-clare-boothe-luce-finding-aid-library-of-congress-pdf-1694480.webp)

Papers of Clare Boothe Luce [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF

Clare Boothe Luce A Register of Her Papers in the Library of Congress Prepared by Nan Thompson Ernst with the assistance of Joseph K. Brooks, Paul Colton, Patricia Craig, Michael W. Giese, Patrick Holyfield, Lisa Madison, Margaret Martin, Brian McGuire, Scott McLemee, Susie H. Moody, John Monagle, Andrew M. Passett, Thelma Queen, Sara Schoo and Robert A. Vietrogoski Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2003 Contact information: http://lcweb.loc.gov/rr/mss/address.html Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 2003 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms003044 Latest revision: 2008 July Collection Summary Title: Papers of Clare Boothe Luce Span Dates: 1862-1988 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1930-1987) ID No.: MSS30759 Creator: Luce, Clare Boothe, 1903-1987 Extent: 460,000 items; 796 containers plus 11 oversize, 1 classified, 1 top secret; 319 linear feet; 41 microfilm reels Language: Collection material in English Repository: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Abstract: Journalist, playwright, magazine editor, U.S. representative from Connecticut, and U.S. ambassador to Italy. Family papers, correspondence, literary files, congressional and ambassadorial files, speech files, scrapbooks, and other papers documenting Luce's personal and public life as a journalist, playwright, politician, member of Congress, ambassador, and government official. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. Personal Names Barrie, Michael--Correspondence. Baruch, Bernard M. -

Hillsdale College Freedom Library Catalog

Hillsdale College Freedom Library Catalog Books from Hillsdale College Press, Back Issues of Imprimis, Seminar CDs and DVDs THOMAS JEFFERSON | ANTHONY FRUDAKIS, SCULPTOR AND ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF ART, HILLSDALE COLLEGE CARSON BHUTTO YORK D'SOUZA STRASSEL WALLACE HANSON PESTRITTO GRAMM ARNN GOLDBERG MORGENSON GILDER JACKSON THATCHER RILEY MAC DONALD FRIEDMAN Hillsdale College Freedom Library Catalog illsdale College is well known for its unique independence and its commitment to freedom and the liberal arts. It rejects the huge federal and state taxpayer subsidies that go to support other American colleges and universities, relying instead on the voluntary Hcontributions of its friends and supporters nationwide. It refuses to submit to the unjust and burdensome regulations that go with such subsidies, and remains free to continue its 170-year-old mission of offering the finest liberal arts education in the land. Its continuing success stands as a powerful beacon to the idea that independence works. This catalog of books, recordings, and back issues of Imprimis makes widely available some of the best writings and speeches around, by some of the smartest and most important people of our time. These writings and speeches are central to Hillsdale’s continuing work of promoting freedom, supporting its moral foundations, and defending its constitutional framework. Contents Hillsdale College Press Books .................................................... 1 Imprimis ...................................................................... 5 Center -

Robert Charles Hill Papers, 1942-1978

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf0p3000wh No online items Register of the Robert Charles Hill Papers, 1942-1978 Processed by Dale Reed; machine-readable finding aid created by James Lake Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 1999 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Register of the Robert Charles 79067 1 Hill Papers, 1942-1978 Register of the Robert Charles Hill Papers, 1942-1978 Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Contact Information Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] Processed by: Dale Reed Date Completed: 1981 Encoded by: James Lake © 1999 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Robert Charles Hill papers, Date (inclusive): 1942-1978 Collection number: 79067 Creator: Hill, Robert Charles, 1917-1978 Collection Size: 183 manuscript boxes, 29 scrapbooks, 73 envelopes, 4 oversize boxes, 9 motion picture film reels, 4 phonotape reels (93.7 linear feet) Repository: Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: Speeches and writings, correspondence, reports, clippings, other printed matter, photographs, motion picture film, and sound recordings, relating to conditions in and American relations with Latin America and Spain, American foreign policy and domestic politics, and the Republican Party. Language: English. Access Collection open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copies of audiovisual items. To listen to sound recordings or to view videos or films during your visit, please contact the Archives at least two working days before your arrival. -

Interview with Stephen F. Dachi

Library of Congress Interview with Stephen F. Dachi The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History ProjectInformation Series STEPHEN F. DACHI Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: May 30, 1997 Copyright 2001 ADST Q: Today is May 30, 1997. This is an interview with Stephen F. Dachi. This is being done on behalf of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. I am Charles Stuart Kennedy. To begin at the beginning, could you tell me when and where you werborn and something about your family? DACHI: I was born in 1933 in Hungary. My father was a dentist. My mother was a physician. They both died when I was three years old in 1936, before the war. My grandparents “inherited me.” They happened to live in Romania. So, I went there just before the Germans marched into Austria, which is my first memory of arriving in Timisoara to live with my grandparents. Then I spent World War II there with them trying to survive. After the war, in 1948, an uncle and aunt who had gone to Canada before the war brought me out there. Q: During the war, what went on then in Romania, particularly as a Hungarian? There was a massive change of borders and everything else at that time. Did you get caught in that? Interview with Stephen F. Dachi http://www.loc.gov/item/mfdipbib000263 Library of Congress DACHI: Very definitely, both that and the Holocaust. It has always been hell for Hungarians living in Romania. Kids would curse and harass us if they overheard us speaking Hungarian in the street. -

Heritage Foundation

LEADING THE FIGHT FOR FREEDOM & OPPORTUNITY ANNUAL REPORT 2012 LEADING THE FIGHT FOR FREEDOM & OPPORTUNITY ANNUAL REPORT 2012 The Heritage Foundation Leading the Fight for Freedom & Opportunity OUR MISSION: To formulate and promote conservative public policies based on the principles of free enterprise, limited government, individual freedom, traditional American values and a strong national defense. BOARD OF TRUSTEES PATRON OF THE HERITAGE FOUNDATION Thomas A. Saunders III, Chairman The Right Honourable The Baroness Thatcher, LG, PC, OM, FRS Richard M. Scaife, Vice Chairman J. Frederic Rench, Secretary SENIOR MANAGEMENT Meg Allen Edwin J. Feulner, Ph.D., President Douglas F. Allison Jim DeMint, President-elect Larry P. Arnn, Ph.D. Phillip N. Truluck, Executive Vice President The Hon. Belden Bell David Addington, Senior Vice President Midge Decter Edwin J. Feulner, Ph.D. Stuart M. Butler, Ph.D., Distinguished Fellow Steve Forbes James Jay Carafano, Ph.D., Vice President Todd W. Herrick Becky Norton Dunlop, Vice President Jerry Hume John Fogarty, Vice President Kay Coles James Michael G. Franc, Vice President The Hon. J. William Middendorf II Michael M. Gonzalez, Vice President Abby Moffat Kim R. Holmes, Ph.D., Distinguished Fellow Nersi Nazari, Ph.D. Geoffrey Lysaught, Vice President Robert Pennington Edwin Meese III, Reagan Distinguished Fellow Emeritus Anthony J. Saliba Derrick Morgan, Vice President William E. Simon, Jr. Matthew Spalding, Ph.D., Vice President Brian Tracy Michael Spiller, Vice President Phillip N. Truluck John Von Kannon, Vice President and Senior Counselor Barb Van Andel-Gaby Genevieve Wood, Vice President Marion G. Wells Robert E. Russell, Jr., Counselor HONORARY CHAIRMAN AND TRUSTEE EMERITUS David R. -

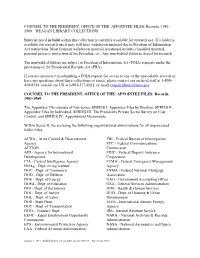

APPOINTEE FILES: Records, 1981- 1989 – REAGAN LIBRARY COLLECTIONS

COUNSEL TO THE PRESIDENT, OFFICE OF THE: APPOINTEE FILES: Records, 1981- 1989 – REAGAN LIBRARY COLLECTIONS Material noted in bold within this collection is currently available for research use. If a folder is available for research use it may still have withdrawn material due to Freedom of Information Act restrictions. Most frequent withdrawn material is national security classified material, personal privacy, protection of the President, etc. Any non-bolded folder is closed for research. The non-bolded folders are subject to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests under the provisions of the Presidential Records Act (PRA). If you are interested in submitting a FOIA request for access to any of the unavailable records or have any questions about these collections or series, please contact our archival staff at 1-800- 410-8354, outside the US at 1-805-577-4012, or email [email protected] COUNSEL TO THE PRESIDENT, OFFICE OF THE: APPOINTEE FILES: Records, 1981-1989 The Appointee File consists of four series: SERIES I: Appointee Files by Position; SERIES II: Appointee Files by Individual; SERIES III: The President's Private Sector Survey on Cost Control, and SERIES IV: Appointment Memoranda Within Series II, we are using the following organizational abbreviations for all unprocessed folder titles: ACDA - Arms Control & Disarmament FBI - Federal Bureau of Investigation Agency FCC - Federal Communications ACTION Commission AID - Agency for International FDIC - Federal Deposit Insurance Development Corporation CIA - Central Intelligence Agency FEMA - Federal Emergency Management DOAg - Dept. of Agriculture Agency DOC - Dept. of Commerce FNMA - Federal National Mortgage DOD - Dept. of Defense Association DOE - Dept. -

Important Figures in the NSC

Important Figures in the NSC Nixon Administration (1969-1973) National Security Council: President: Richard Nixon Vice President: Spiro Agnew Secretary of State: William Rogers Secretary of Defense: Melvin Laird Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs (APNSA): Henry Kissinger Director of CIA: Richard Helms Chairman of Joint Chiefs: General Earle Wheeler / Admiral Thomas H. Moorer Director of USIA: Frank Shakespeare Director of Office of Emergency Preparedness: Brig. Gen. George Lincoln National Security Council Review Group (established with NSDM 2) APNSA: Henry A. Kissinger Rep. of Secretary of State: John N. Irwin, II Rep. of Secretary of Defense: David Packard, Bill Clements Rep. of Chairman of Joint Chiefs: Adm. Thomas H. Moorer Rep. of Director of CIA: Richard Helms, James R. Schlesinger, William E. Colby National Security Council Senior Review Group (NSDM 85—replaces NSCRG/ NSDM 2) APNSA: Henry A. Kissinger Under Secretary of State: Elliott L. Richardson / John N. Irwin, II Deputy Secretary of Defense: David Packard / Bill Clements Director of Central Intelligence: Richard Helms Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff: General Earle Wheeler / Admiral Thomas H. Moorer Under Secretary’s Committee: Under Secretary of State: Elliott L. Richardson / John N. Irwin, II APNSA: Henry Kissinger Deputy Secretary of Defense: David Packard / Bill Clements Chairman of Joint Chiefs: Gen. Earle G. Wheeler / Adm. Thomas H. Moorer Director of CIA: Richard M. Helms Nixon/Ford Administration (1973-1977) National Security Council: President: Richard Nixon (1973-1974) Gerald Ford (1974-1977) Vice President: Gerald Ford (1973-1974) Secretary of State: Henry Kissinger Secretary of Defense: James Schlesinger / Donald Rumsfeld APNSA: Henry Kissinger / Brent Scowcroft Director of CIA: Richard Helms / James R. -

Robert Charles Hill Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf0p3000wh Online items available Register of the Robert Charles Hill papers Finding aid prepared by Dale Reed and James Lake Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 1999 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the Robert Charles 79067 1 Hill papers Title: Robert Charles Hill papers Date (inclusive): 1929-1978 Collection Number: 79067 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 183 manuscript boxes, 73 envelopes, 29 oversize boxes, 1 oversize folder, 9 motion picture film reels, 4 sound tape reels(125.0 Linear Feet) Abstract: Speeches and writings, correspondence, reports, clippings, other printed matter, photographs, motion picture film, and sound recordings relating to conditions in and American relations with Latin America and Spain, American foreign policy and domestic politics, and the Republican Party. Digital copies of select records also available at https://digitalcollections.hoover.org. Creator: Hill, Robert Charles, 1917-1978 Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1979. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Robert Charles Hill papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Alternate Forms Available Digital copies of select records also available at https://digitalcollections.hoover.org. 1917 September Born, Littleton, New Hampshire 30 1941-1944 Washington, D.C., representative, New England Shipbuilding Corporation 1944-1945 U.S. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS January 27, 1969 Col

1882 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS January 27, 1969 Col. Ray M. Cole, FR15568, Regular Air Col. W1111am C. Fullllove, FR15853, Regu Col. John W. Roberts, FR15280, Regular Force. lar Air Force. Air Force. Col. Michael C. McCarthy, FR9721, Regular Col. Charles E. Yeager, FR16076, Regular Col. Brian S. Gunderson, FR60308, Regular Air Force. Air Force. Air Force. Col. Jessup D. Lowe, FR9807, Regular Air Col. Harold R . Vague, FR22991, Regular Col. Geol!rey Cheadle, FR15830, Regular Force. Air Force. Air Force. Col. Donald A. Gaylord, FR10003, Regular Col. Paul G. Galentine, Jr., FR14734, Reg Col. Floyd H. Trogdon, FR16737, Regular Air Force. ular Air Force. Air Force. Col. Vernon R. Turner, FR10146, Regular Col. Foster L. Smith, FR15882, Regular Air Force. Air Force. Col. Devol Brett, FRl 7000, Regular Air Col. Edgar H. Underwood, Jr., FR19262, Col. Thomas P . Coleman, FR13283, Regular Force. Regular Air Force, Medical. Air Force. Col. Paul F. Patch, FR35545, Regular Air Col. Coleman 0. Williams, Jr., FR9709, Col. Homer K. Hansen, FR14983, Regular Force. Regular Air Force. Air Force. Col. Harold E. Collins, FR17200, Regular Col. Leslie J. Westberg, FR35854, Regular Col. Peter R. DeLonga, FR15567, Regular Air Force. Air Force. Air Force. Col. Benjamin N. Bellis, FRl7330 {lieuten Col. George K. Sykes, FR9763, Regular Air Col. Clil!ord W. Hargrove, FR10038, Regu ant colonel, Regular Air Force), U.S. Air Force. lar Air Force. Force. Col. Wendell L. Bevan, Jr., FR9780, Regular Col. Samuel M. Thomasson, FR20025, Reg Col. Salvador E. Felices, FR17377 (lieuten Air Force. ular Air Force. ant colonel, Regular Air Force) U.S.