Interpretation of Torture in the Light of the Practice and Jurisprudence of International Bodies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modern-Day Slavery & Human Rights

& HUMAN RIGHTS MODERN-DAY SLAVERY MODERN SLAVERY What do you think of when you think of slavery? For most of us, slavery is something we think of as a part of history rather than the present. The reality is that slavery still thrives in our world today. There are an estimated 21-30 million slaves in the world today. Today’s slaves are not bought and sold at public auctions; nor do their owners hold legal title to them. Yet they are just as surely trapped, controlled and brutalized as the slaves in our history books. What does slavery look like today? Slaves used to be a long-term economic investment, thus slaveholders had to balance the violence needed to control the slave against the risk of an injury that would reduce profits. Today, slaves are cheap and disposable. The sick, injured, elderly and unprofitable are dumped and easily replaced. The poor, uneducated, women, children and marginalized people who are trapped by poverty and powerlessness are easily forced and tricked into slavery. Definition of a slave: A person held against his or her will and controlled physically or psychologically by violence or its threat for the purpose of appropriating their labor. What types of slavery exist today? Bonded Labor Trafficking A person becomes bonded when their labor is demanded This involves the transport and/or trade of humans, usually as a means of repayment of a loan or money given in women and children, for economic gain and involving force advance. or deception. Often migrant women and girls are tricked and forced into domestic work or prostitution. -

Representations and Discourse of Torture in Post 9/11 Television: an Ideological Critique of 24 and Battlestar Galactica

REPRESENTATIONS AND DISCOURSE OF TORTURE IN POST 9/11 TELEVISION: AN IDEOLOGICAL CRITIQUE OF 24 AND BATTLSTAR GALACTICA Michael J. Lewis A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2008 Committee: Jeffrey Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin ii ABSTRACT Jeffrey Brown Advisor Through their representations of torture, 24 and Battlestar Galactica build on a wider political discourse. Although 24 began production on its first season several months before the terrorist attacks, the show has become a contested space where opinions about the war on terror and related political and military adventures are played out. The producers of Battlestar Galactica similarly use the space of television to raise questions and problematize issues of war. Together, these two television shows reference a long history of discussion of what role torture should play not just in times of war but also in a liberal democracy. This project seeks to understand the multiple ways that ideological discourses have played themselves out through representations of torture in these television programs. This project begins with a critique of the popular discourse of torture as it portrayed in the popular news media. Using an ideological critique and theories of televisual realism, I argue that complex representations of torture work to both challenge and reify dominant and hegemonic ideas about what torture is and what it does. This project also leverages post-structural analysis and critical gender theory as a way of understanding exactly what ideological messages the programs’ producers are trying to articulate. -

Publicationsthe Prohibition of Torture

THE PROHIBITION OF TORTURE: AN INTRODUCTORY GUIDE This is a publication of the Center for Hu- man Rights & Humanitarian Law at American University College of Law — authored by Associate Director of Impact Litigation and the Kovler Project Against Torture Jennifer de Laurentiis and Assistant Director of the Anti- Torture Initiative Andra Nicolescu, and designed by Center Program Coordinator Anastassia Fagan. TABLE OF CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM DEAN CAMILLE A. NELSON.......................................................................................................i MESSAGE FROM CENTER DIRECTOR, PROFESSOR MACARENA SAEZ.........................................................ii INTRODUCTION: WHY DOES THE PROHIBITION OF TORTURE AND OTHER ILL-TREATMENT MATTER?...............................................................................................................1 WHAT IS TORTURE?.....................................................................................................................................................2 WHAT ARE “OTHER ACTS OF CRUEL, INHUMAN OR DEGRADING TREATMENT OR PUNISHMENT WHICH DO NOT AMOUNT TO TORTURE?”...................................................5 WHAT IS THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN TORTURE & OTHER ILL-TREATMENT?...........................................6 CAN PRIVATE ACTORS COMMIT “TORTURE”?......................................................................................................7 WHAT DOES THE CONVENTION AGAINST TORTURE REQUIRE?.....................................................................9 -

The Right to Reparations for Acts of Torture: What Right, What Remedies?*

96 STATE OF THE ART The right to reparations for acts of torture: what right, what remedies?* Dinah Shelton** 1. Introduction international obligation must cease and the In all legal systems, one who wrongfully wrong-doing state must repair the harm injures another is held responsible for re- caused by the illegal act. In the 1927 Chor- dressing the injury caused. Holding the zow Factory case, the PCIJ declared dur- wrongdoer accountable to the victim serves a ing the jurisdictional phase of the case that moral need because, on a practical level, col- “reparation … is the indispensable comple- lective insurance might just as easily provide ment of a failure to apply a convention and adequate compensation for losses and for fu- there is no necessity for this to be stated in ture economic needs. Remedies are thus not the convention itself.”1 Thus, when rights only about making the victim whole; they are created by international law and a cor- express opprobrium to the wrongdoer from relative duty imposed on states to respect the perspective of society as a whole. This those rights, it is not necessary to specify is incorporated in prosecution and punish- the obligation to afford remedies for breach ment when the injury stems from a criminal of the obligation, because the duty to repair offense, but moral outrage also may be ex- emerges automatically by operation of law; pressed in the form of fines or exemplary or indeed, the PCIJ has called the obligation of punitive damages awarded the injured party. reparation part of the general conception of Such sanctions express the social convic- law itself.2 tion that disrespect for the rights of others In a later phase of the same case, the impairs the wrongdoer’s status as a moral Court specified the nature of reparations, claimant. -

The Politics of Torture in Great Britain, the United States, and Argentina, 1869-1977

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2014 Holes in the Historical Record: The olitP ics of Torture in Great Britain, the United States, and Argentina, 1869-1977 Lynsey Chediak Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Chediak, Lynsey, "Holes in the Historical Record: The oP litics of Torture in Great Britain, the United States, and Argentina, 1869-1977" (2014). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 875. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/875 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE Holes in the Historical Record: The Politics of Torture in Great Britain, the United States, and Argentina, 1869-1977 SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR LISA FORMAN CODY AND DEAN NICHOLAS WARNER BY LYNSEY CHEDIAK FOR SENIOR HISTORY THESIS SPRING 2014 April 28, 2014 Acknowledgments This thesis would not have been possible without the brilliant minds of my professors at Claremont McKenna College and the encouragement of my family. First, I would like to thank my reader and advisor, Professor Lisa Forman Cody. From my first day in her class, Professor Cody took what I was trying to say and made my statement, and me, sound ten times smarter. From that moment, I started to truly believe in the power of my ideas and a central tenet that made this thesis possible: there is no wrong answer in history, only evidence. Through countless hours of collaboration, Professor Cody spurred my ideas to levels I never could have imagined and helped me to develop my abilities to think critically and analytically of the historical record and the accuracy of sources. -

Reproductive Rights Violations As Torture Or Ill-Treatment

REPRODUCTIVE RIGHTS VIOLATIONS AS TORTURE OR ILL-TREATMENT CAT Committee Jurisprudence on Violations of Reproductive Rights The Committee against Torture (CAT Committee) has found that several restrictions on access to reproductive health services and abuses that occur when seeking these services may constitute violations of the Convention against Torture (CAT) because they put women’s health and lives at risk or may otherwise cause them severe physical or mental pain or suffering. For instance, the CAT Committee has found that complete bans on abortion, which exist in only five countries in the world (Nicaragua, El Salvador, Chile, Malta, and the Dominican Republic) may constitute torture or ill-treatment on their face, because these laws place women at a risk of preventable maternal mortality. • As the CAT Committee noted in its 2009 review of El Salvador, “the current Criminal Code of 1998 penalizes and punishes with imprisonment for periods ranging from 6 months to 12 years all forms of recourse to voluntary interruption of pregnancy, including in cases of rape or incest, which has resulted in serious harm to women, including death,” recommending that El Salvador take measure to prevent torture and ill-treatment by “providing the required medical treatment, by strengthening family planning programmes and by offering better access to information and reproductive health services, including for adolescents.”1 The CAT Committee has also recommended that abortion be legal in a variety of instances where a pregnancy may cause a woman severe physical or mental suffering. To date, the CAT Committee has found that states have an obligation to ensure access to abortion for women whose health or life is at risk, who are the victims of sexual violence, or who are carrying non- viable fetuses. -

Teacher Lesson Plan an Introduction to Human Rights and Responsibilities

Teacher Lesson Plan An Introduction to Human Rights and Responsibilities Lesson 2: Introduction to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights Note: The Introduction to Human Rights and Responsibilities resource has been designed as two unique lesson plans. However, depending on your students’ level of engagement and the depth of content that you wish to explore, you may wish to divide each lesson into two. Each lesson consists of ‘Part 1’ and ‘Part 2’ which could easily function as entire lessons on their own. Key Learning Areas Humanities and Social Sciences (HASS); Health and Physical Education Year Group Years 5 and 6 Student Age Range 10-12 year olds Resources/Props • Digital interactive lesson - Introduction to Human Rights and Responsibilities https://www.humanrights.gov.au/introhumanrights/ • Interactive Whiteboard • Note-paper and pens for students • Printer Language/vocabulary Human rights, responsibilities, government, children’s rights, citizen, community, individual, law, protection, values, beliefs, freedom, equality, fairness, justice, dignity, discrimination. Suggested Curriculum Links: Year 6 - Humanities and Social Sciences Inquiry Questions • How have key figures, events and values shaped Australian society, its system of government and citizenship? • How have experiences of democracy and citizenship differed between groups over time and place, including those from and in Asia? • How has Australia developed as a society with global connections, and what is my role as a global citizen?” Inquiry and Skills Questioning • -

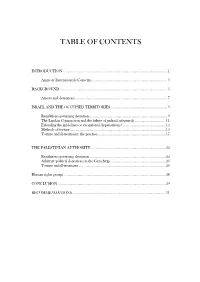

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 1 Amnesty International's Concerns ..................................................................................... 3 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................... 5 Arrests and detentions ........................................................................................................ 7 ISRAEL AND THE OCCUPIED TERRITORIES ................................................................ 9 Regulations governing detention ........................................................................................ 9 The Landau Commission and the failure of judicial safeguards ................................. 11 Extending the guidelines or exceptional dispensations? ................................................ 14 Methods of torture ............................................................................................................ 15 Torture and ill-treatment: the practice ............................................................................. 17 THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY .................................................................................... 22 Regulations governing detention ...................................................................................... 22 Arbitrary political detentions in the Gaza Strip .............................................................. -

“We Will Make You Regret Everything”

“We will make you Torture in Iran since regret everything” the 2009 elections Freedom from Torture Country Reporting Programme March 2013 Freedom from Torture Country Reporting Programme March 2013 “We will make you regret everything” Torture in Iran since the 2009 elections “Why did this happen to me, what did I do wrong? ...They’ve made me hate my body to a point that I don’t want to shower or get dressed... I feel alone and can’t trust another person.” Case study - Sanaz, page 6 3 Table of Contents Summary and key findings ............................................................. 7 Key findings of the report .................................................................... 8 Recommendations .......................................................................... 10 Introduction ................................................................................... 11 Freedom from Torture’s history of working with Iranian torture survivors 11 Case sample and method ..................................................................... 11 1. Case Profile ............................................................................................ 12 a. Place of origin and place of residence when detained .................................. 12 b. Ethnicity and religious identity .............................................................. 12 c. Ordinary occupation .......................................................................... 13 d. History of activism or dissent .............................................................. -

Torture and the Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment of Detainees: the Effectiveness and Consequences of 'Enhanced

TORTURE AND THE CRUEL, INHUMAN AND DE- GRADING TREATMENT OF DETAINEES: THE EFFECTIVENESS AND CONSEQUENCES OF ‘EN- HANCED’ INTERROGATION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON THE CONSTITUTION, CIVIL RIGHTS, AND CIVIL LIBERTIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 8, 2007 Serial No. 110–94 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://judiciary.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 38–765 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:46 Jul 29, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\WORK\CONST\110807\38765.000 HJUD1 PsN: 38765 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan, Chairman HOWARD L. BERMAN, California LAMAR SMITH, Texas RICK BOUCHER, Virginia F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., JERROLD NADLER, New York Wisconsin ROBERT C. ‘‘BOBBY’’ SCOTT, Virginia HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina ELTON GALLEGLY, California ZOE LOFGREN, California BOB GOODLATTE, Virginia SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas STEVE CHABOT, Ohio MAXINE WATERS, California DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California WILLIAM D. DELAHUNT, Massachusetts CHRIS CANNON, Utah ROBERT WEXLER, Florida RIC KELLER, Florida LINDA T. SA´ NCHEZ, California DARRELL ISSA, California STEVE COHEN, Tennessee MIKE PENCE, Indiana HANK JOHNSON, Georgia J. RANDY FORBES, Virginia BETTY SUTTON, Ohio STEVE KING, Iowa LUIS V. GUTIERREZ, Illinois TOM FEENEY, Florida BRAD SHERMAN, California TRENT FRANKS, Arizona TAMMY BALDWIN, Wisconsin LOUIE GOHMERT, Texas ANTHONY D. -

The Death Penalty As Torture

The Death Penalty as Torture bessler DPT last pages.indb 1 1/12/17 11:47 AM Also by John D. Bessler Death in the Dark: Midnight Executions in Amer i ca Kiss of Death: Amer i ca’s Love Affair with the Death Penalty Legacy of Vio lence: Lynch Mobs and Executions in Minnesota Writing for Life: The Craft of Writing for Everyday Living Cruel and Unusual: The American Death Penalty and the Found ers’ Eighth Amendment The Birth of American Law: An Italian Phi los o pher and the American Revolution Against the Death Penalty (editor) bessler DPT last pages.indb 2 1/12/17 11:47 AM The Death Penalty as Torture From the Dark Ages to Abolition John D. Bessler Carolina Academic Press Durham, North Carolina bessler DPT last pages.indb 3 1/12/17 11:47 AM Copyright © 2017 John D. Bessler All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Bessler, John D., author. Title: The death penalty as torture : from the dark ages to abolition / John D. Bessler. Description: Durham, North Carolina : Carolina Academic Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016036253 | ISBN 9781611639261 (alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Capital punishment--History. | Capital punishment--United States. Classification: LCC K5104 .B48 2016 | DDC 345/.0773--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016036253 Carolina Academic Press, LLC 700 Kent Street Durham, North Carolina 27701 Telephone (919) 489-7486 Fax (919) 493-5668 www.cap-press.com Printed in the United States of America bessler DPT last pages.indb 4 1/12/17 11:47 AM For all victims of torture bessler DPT last pages.indb 5 1/12/17 11:47 AM bessler DPT last pages.indb 6 1/12/17 11:47 AM “Can the state, which represents the whole of society and has the duty of protect- ing society, fulfill that duty by lowering itself to the level of the murderer, and treating him as he treated others? The forfeiture of life is too absolute, too irre- versible, for one human being to inflict it on another, even when backed by legal process.” — U.N. -

Redress for Rape

Redress for Rape Using international jurisprudence on rape as a form of torture or other ill-treatment October 2013 REDRESS 87 Vauxhall Walk London, SE11 5HJ United Kingdom +44 20 7793 1777 www.redress.org CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 PART I: CONTEXT & CONTROVERSIES .................................................................... 4 A. UNDERSTANDINGS OF TORTURE AND OTHER ILL-TREATMENT ................................... 4 1. The prohibition of torture and other ill-treatment in international law .................... 4 2. Understandings of torture and other ill-treatment .................................................... 6 2.1. Distinguishing torture and other ill-treatment ................................................ 6 2.2. Other ill-treatment under international human rights law ............................. 7 2.3. Torture under international human rights law ................................................ 8 2.4. Torture in international criminal law ............................................................... 9 2.5. Current jurisprudence on the distinction between torture and other ill- treatment in international human rights law ................................................ 11 B. ADDRESSING THE BLIND SPOT: RECOGNISING RAPE AS TORTURE OR OTHER ILL- TREATMENT ........................................................................................................... 16 1. Rape in the international legal sphere ....................................................................