Interview with Ken Olsen Digital Equipment Corporation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Details of the Elliott 152 and 153

Appendix 1 Technical Details of the Elliott 152 and 153 Introduction The Elliott 152 computer was part of the Admiralty’s MRS5 (medium range system 5) naval gunnery project, described in Chap. 2. The Elliott 153 computer, also known as the D/F (direction-finding) computer, was built for GCHQ and the Admiralty as described in Chap. 3. The information in this appendix is intended to supplement the overall descriptions of the machines as given in Chaps. 2 and 3. A1.1 The Elliott 152 Work on the MRS5 contract at Borehamwood began in October 1946 and was essen- tially finished in 1950. Novel target-tracking radar was at the heart of the project, the radar being synchronized to the computer’s clock. In his enthusiasm for perfecting the radar technology, John Coales seems to have spent little time on what we would now call an overall systems design. When Harry Carpenter joined the staff of the Computing Division at Borehamwood on 1 January 1949, he recalls that nobody had yet defined the way in which the control program, running on the 152 computer, would interface with guns and radar. Furthermore, nobody yet appeared to be working on the computational algorithms necessary for three-dimensional trajectory predic- tion. As for the guns that the MRS5 system was intended to control, not even the basic ballistics parameters seemed to be known with any accuracy at Borehamwood [1, 2]. A1.1.1 Communication and Data-Rate The physical separation, between radar in the Borehamwood car park and digital computer in the laboratory, necessitated an interconnecting cable of about 150 m in length. -

Chapter 1 Computer Basics

Chapter 1 Computer Basics 1.1 History of the Computer A computer is a complex piece of machinery made up of many parts, each of which can be considered a separate invention. abacus Ⅰ. Prehistory /ˈæbəkəs/ n. 算盘 The abacus, which is a simple counting aid, might have been invented in Babylonia(now Iraq) in the fourth century BC. It should be the ancestor of the modern digital calculator. Figure 1.1 Abacus Wilhelm Schickard built the first mechanical calculator in 1623. It can loom work with six digits and carry digits across columns. It works, but never /lu:m/ makes it beyond the prototype stage. n. 织布机 Blaise Pascal built a mechanical calculator, with the capacity for eight digits. However, it had trouble carrying and its gears tend to jam. punch cards Joseph-Marie Jacquard invents an automatic loom controlled by punch 穿孔卡片 cards. Difference Engine Charles Babbage conceived of a Difference Engine in 1820. It was a 差分机 massive steam-powered mechanical calculator designed to print astronomical tables. He attempted to build it over the course of the next 20 years, only to have the project cancelled by the British government in 1842. 1 新编计算机专业英语 Analytical Engine Babbage’s next idea was the Analytical Engine-a mechanical computer which 解析机(早期的机 could solve any mathematical problem. It used punch-cards similar to those used 械通用计算机) by the Jacquard loom and could perform simple conditional operations. countess Augusta Ada Byron, the countess of Lovelace, met Babbage in 1833. She /ˈkaʊntɪs/ described the Analytical Engine as weaving “algebraic patterns just as the n. -

TX-0 Computer After 10,000 Hours of Operation", L

tX If ,@8s~~~I 17A .:~- I-:· aTg Dc''n'_ !-41 2 . LK - ! v M IT6u i ~~6:illn -jW-~ 4 1 2 The RESEARCH LABORATORY of ELECTRONICS at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS 02139 TX-O Computer History John A. McKenzie RLE Technical Report No. 627 June 1999 MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH LABORATORY OF ELECTRONICS CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS 02139 TX-O COMPUTER HISTORY John A. McKenzie October 1, 1974 TX-O COMPUTER HISTORY OUTLINE ABSTRA CT PART I (at LINCOLN ABORATORY) INTRODUCTION 1 DESCRIPTION 2 LOGIC 4 CIRCUITRY 5 MARGINAL CHECKING 6 TRANSISTORS MEMORY (S Memory) SOFTWARE (Initial) 9 TX-2 10 TRANSISTORIZED MEMORY (T Memory) 11 POWER CONTROL 12 IN-OUT RACK 13 CONSOLE 13 PART II (at CAMBRIDGE) INTRODUCTION 14 MOVE to CAMBRIDGE 15 EXTENDED INPUT/OUTPUT FACILITY, Addition of 16 FIRST YEAR at CAMBRIDGE 18 MODE of OPERATION 19 MACHINE EXPANSION PHASE 20 T-MEMORY EXPANSION 21 ORDER CODE ENLARGEMENT 22 DIGITAL MAGNETIC TAPE SYSTEM 24 SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT 25 APPLICATIONS 29 TIMESHARING (PDP-1) 34 CONCLUSION 34 A CKNOWLEDGEMENT 35 BIBLIOGRAPHY TX-O COMPUTER HISTORY A BSTRA CT The TX-O Computer (meaning the Zeroth Transistorized Computer) was designed and constructed, in 1956, by the Lincoln Laboratory of the Massachusetts Institute of Tech- nology, with two purposes in mind. One objective was to test and evaluate the use of transistors as the logical elements of a high-speed, 5 MHz, general-purpose, stored-program, parallel, digital computer. The second purpose was to provide means for testing a large capacity (65,536 word) magnetic-core memory. -

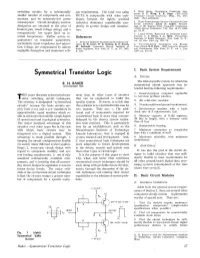

Symmetrical Transistor Logic A

switching circuits by a substantially- age requirements. The total cost using 2. HIGH SPEED TRANSISTOR COMPUTER CIR CUITS, S. Y. Wong;, A. K. Rapp. IRE-AIEE smaller number of components and con DCTL is comparable with other tech Transistor Circuits Conference, Phila., Pa., Feb. nections, and by extremely-low power niques, because the tightly specified 1956. (Not published.) consumption. Circuit simplicity and low 3. HIGH-TEMPERATURE SILICON-TRANSISTOR COM transistor eliminates considerable com PUTER CIRCUITS, James B. Angell. Proceed dissipation are obtained at the price of plexity in system design and manufac ings of the Eastern • Joint Computer Conference, AIEE Special Publication T-92, Dec. 10-12, 1956, limited gain, small voltage swings, and a ture. pp. 54-57. comparatively low upper limit on in 4. LARGE-SIGNAL BEHAVIOR OP JUNCTION TRAN ternal temperature. Rather severe re SISTORS, J. J. Ebeijs, J. L. Moll. Proceedings, References Institute of Radio Engineers, New York, N. Y., quirements on transistor parameters, vol. 42, Dec. 1954, ij>p. 1761-72. 1. SURFACE-BARRIER TRANSISTOR SWITCHING CIR particularly input impedance and satura CUITS, R. H. Beter, W. E. Bradley, R. B. Brown, 5. TWO-COLLECTOR TRANSISTOR FOR BINARY tion voltage, are compensated by almost M. Rubinoff. Convention Record, Institute of FULL ADDER, R. F. Rtitz. IBM Journal of Research Radio Engineers, New York, N. Y., pt. IV, 1955, and Development, N^w York, N. Y., vol. 1, July negligible dissipation and maximum volt p. 139. 1957, pp. 212-22. I. Basic System Requirements Symmetrical Transistor Logic A. INITIAL The initial specific system for which the R. -

Talking About the Development Trend of Modern Computer Technology

2019 3rd International Conference on Computer Engineering, Information Science and Internet Technology (CII 2019) Talking about the Development Trend of Modern Computer Technology Yongpan Wang North China Electric Power University, Baoding 071000, China [email protected] Keywords: modern computer technology; development status; development trend. Abstract: Along with the development of the times and the advancement of society, the popularity of computer technology has not only changed the way people communicate, but also brought more help to economic development. Computer technology promotes the development of China's social economy and information security industry, but security risk management is still an urgent problem in the development of modern computer technology. The analysis from the development history of the computer can explore its technological development direction, and can also predict its development trend and contribute to the overall development of society. Therefore, this paper mainly discusses the development history of computer technology, analyzes its development status, and explores its development direction based on the above research. 1. Introduction The so-called computer is a modern intelligent electronic device that can be used for high-speed data and logic computing and with storage and modification functions. Computer belongs to a common item in our work life. It mainly has two parts of the main structure, some of which can be called hardware system, which is composed of hardware, which maintains the operation of the computer, and the other part is the software system to realize the function of the computer. The two together guarantee the normal operation of the computer. With the continuous advancement of science and technology, modern computer technology is also developing. -

The People Who Invented the Internet Source: Wikipedia's History of the Internet

The People Who Invented the Internet Source: Wikipedia's History of the Internet PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Sat, 22 Sep 2012 02:49:54 UTC Contents Articles History of the Internet 1 Barry Appelman 26 Paul Baran 28 Vint Cerf 33 Danny Cohen (engineer) 41 David D. Clark 44 Steve Crocker 45 Donald Davies 47 Douglas Engelbart 49 Charles M. Herzfeld 56 Internet Engineering Task Force 58 Bob Kahn 61 Peter T. Kirstein 65 Leonard Kleinrock 66 John Klensin 70 J. C. R. Licklider 71 Jon Postel 77 Louis Pouzin 80 Lawrence Roberts (scientist) 81 John Romkey 84 Ivan Sutherland 85 Robert Taylor (computer scientist) 89 Ray Tomlinson 92 Oleg Vishnepolsky 94 Phil Zimmermann 96 References Article Sources and Contributors 99 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 102 Article Licenses License 103 History of the Internet 1 History of the Internet The history of the Internet began with the development of electronic computers in the 1950s. This began with point-to-point communication between mainframe computers and terminals, expanded to point-to-point connections between computers and then early research into packet switching. Packet switched networks such as ARPANET, Mark I at NPL in the UK, CYCLADES, Merit Network, Tymnet, and Telenet, were developed in the late 1960s and early 1970s using a variety of protocols. The ARPANET in particular led to the development of protocols for internetworking, where multiple separate networks could be joined together into a network of networks. In 1982 the Internet Protocol Suite (TCP/IP) was standardized and the concept of a world-wide network of fully interconnected TCP/IP networks called the Internet was introduced. -

Sperry Rand's Third-Generation Computers 1964–1980

Sperry Rand’s Third-Generation Computers 1964–1980 George T. Gray and Ronald Q. Smith The change from transistors to integrated circuits in the mid-1960s marked the beginning of third-generation computers. A late entrant (1962) in the general-purpose, transistor computer market, Sperry Rand Corporation moved quickly to produce computers using ICs. The Univac 1108’s success (1965) reversed the company’s declining fortunes in the large-scale arena, while the 9000 series upheld its market share in smaller computers. Sperry Rand failed to develop a successful minicomputer and, faced with IBM’s dominant market position by the end of the 1970s, struggled to maintain its position in the computer industry. A latecomer to the general-purpose, transistor would be suitable for all types of processing. computer market, Sperry Rand first shipped its With its top management having accepted the large-scale Univac 1107 and Univac III comput- recommendation, IBM began work on the ers to customers in the second half of 1962, System/360, so named because of the intention more than two years later than such key com- to cover the full range of computing tasks. petitors as IBM and Control Data. While this The IBM 360 did not rely exclusively on lateness enabled Sperry Rand to produce rela- integrated circuitry but instead employed a tively sophisticated products in the 1107 and combination of separate transistors and chips, III, it also meant that they did not attain signif- called Solid Logic Technology (SLT). IBM made icant market shares. Fortunately, Sperry’s mili- a big event of the System/360 announcement tary computers and the smaller Univac 1004, on 7 April 1964, holding press conferences in 1005, and 1050 computers developed early in 62 US cities and 14 foreign countries. -

Bill Terry Interview 4, November 27, 1995

Bill Terry Interview 4, November 27, 1995 KIRBY: This is Dave Kirby and I’m about to conduct another interview with Bill Terry. Today’s date is November 27, 1995, and we are in HP’s offices at 1501 Page Mill Road, Palo Alto. KIRBY: Okay, very good. Bill, in 1966, when you were marketing manager at Colorado Springs, HP ... Hewlett Packard Laboratories was created. Its purpose, according to the 1966 annual report, was "to provide the company with a broader base of fundamental research and to support the divisions with a source of advance knowledge on materials, processes and techniques." My question is, how was this viewed out in the divisions? Was it overdue? Or was the timing about right? TERRY: I think ... my recollection, Dave, it was viewed as a "ho-hum". I don’t ... unless I go back and really study what happened, it was just an affirmation what the labs were... what the labs had been doing all the time, and maybe a little bit of restatement of the role in helping the divisions as opposed to just doing esoteric research on their own. And maybe it was a little bit of that push toward division communication and division service, if you will, rather than research. But at least in a place like Colorado Springs, and I think most of the divisions, it was a kind of a "life goes on; nothing is really changed". Barney is running the labs; Barney is the source of a lot of ideas and they got a lot of good people in the labs. -

KEN OLSEN Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC)

KEN OLSEN Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) Introduction Ken Olsen co-founded the Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) in 1956. Under his leadership DEC invented and the dominated the minicomputer industry for over 30 years. DEC’s success was an impressive technology story and an impressive corporate culture story. It was so impressive that in 1986 Fortune named Olsen “America’s most successful entrepreneur.” Five years later Olsen resigned under pressure, the victim of DEC’s sudden loss of competitiveness due to changes in the market environment. In spite of that unfortunate ending, Olsen’s earlier accomplishments earned him the continued respect and admiration of those who worked for him and those who followed DEC’s history closely. The Founder’s Background Ken Olsen was born in Stratford, Connecticut in 1926. His parents, Oswald and Elizabeth Olsen were second generation Scandinavian immigrants (Norway and Sweden). Ken and his three siblings grew up in a Norwegian working-class community. As an adult, Ken came close to continuing the Scandinavian tradition by marrying Eeva-Lisa Aulikki from Finland. Ken’s father was first a designer of machine tools (He held several patents) and later a machine salesman for Baird Machine Company in Stratford, Connecticut. He had a shop in the basement at home where he taught Ken and his two brothers the basic skills of the trade. “Ken and Stan (Ken’s younger brother) spent hours down there, inventing gadgets and repairing their neighbors’ broken radios.( Rifkin, p.27). Ken’s father was also, “a fundamentalist by religion and a disciplinarian by nature. He believed in puritan ethics, applied to both life and work. -

The Rise and Fall of Digital Equipment Corporation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Commons @ Assumption College Digital Commons @ Assumption University Management, Marketing, and Organizational Management, Marketing, and Organizational Communication Department Faculty Works Communication Department 2019 Technology Change or Resistance to Changing Institutional Logics: The Rise and Fall of Digital Equipment Corporation Michael S. Lewis Assumption College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.assumption.edu/business-faculty Part of the Business Commons Recommended Citation Lewis, M. S. (2019). Technology Change or Resistance to Changing Institutional Logics: The Rise and Fall of Digital Equipment Corporation. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science . https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0021886318822305 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Management, Marketing, and Organizational Communication Department at Digital Commons @ Assumption University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Management, Marketing, and Organizational Communication Department Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Assumption University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Technology Change or Resistance to Changing Institutional Logics: The Rise and Fall of Digital Equipment Corporation Michael S. Lewis Assistant Professor of Management Assumption College 500 Salisbury Street Worcester, MA 01609-1296 Telephone: 508-767-7372 Fax: 508-767-7252 [email protected] Abstract This article uses an institutional lens to analyze organizational failure. It does this through a historical case study of Digital Equipment Corporation, an innovator and market leader of minicomputers who faltered and eventually failed during the period of technological change brought on by the emergence of the personal computer. -

VAX VMS at 20

1977–1997... and beyond Nothing Stops It! Of all the winning attributes of the OpenVMS operating system, perhaps its key success factor is its evolutionary spirit. Some would say OpenVMS was revolutionary. But I would prefer to call it evolutionary because its transition has been peaceful and constructive. Over a 20-year period, OpenVMS has experienced evolution in five arenas. First, it evolved from a system running on some 20 printed circuit boards to a single chip. Second, it evolved from being proprietary to open. Third, it evolved from running on CISC-based VAX to RISC-based Alpha systems. Fourth, VMS evolved from being primarily a technical oper- ating system, to a commercial operat- ing system, to a high availability mission-critical commercial operating system. And fifth, VMS evolved from time-sharing to a workstation environment, to a client/server computing style environment. The hardware has experienced a similar evolution. Just as the 16-bit PDP systems laid the groundwork for the VAX platform, VAX laid the groundwork for Alpha—the industry’s leading 64-bit systems. While the platforms have grown and changed, the success continues. Today, OpenVMS is the most flexible and adaptable operating system on the planet. What start- ed out as the concept of ‘Starlet’ in 1975 is moving into ‘Galaxy’ for the 21st century. And like the universe, there is no end in sight. —Jesse Lipcon Vice President of UNIX and OpenVMS Systems Business Unit TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I Changing the Face of Computing 4 CHAPTER II Setting the Stage 6 CHAPTER -

Ken Olsen Was Born in Bridgeport, Connecticut, in 1926 and Grew up in the Neighboring Town of Stratford

KenOlsen Kenneth Harry Olsen’s early experiences, both as a child and as a young man in the U.S. Navy, put him on the road to becoming a topnotch engineer and entrepreneur. His early life centered on machines and elec- tronics, laying the foundations for his future work with computers. A Love of Machines and Electronics Ken Olsen was born in Bridgeport, Connecticut, in 1926 and grew up in the neighboring town of Stratford. His father came from Norway, and his mother, from Sweden. His father was a designer of machine tools and imbued Ken and his two brothers with his interest in machines. Much of the boys’ spare time was spent in the family’s basement tinkering with tools and repairing neighbors’ radios.1 All three boys became engineers. Olsen was drafted in World War II and was sent to the Navy’s electron- ics school, where he learned to maintain the radar, sonar, navigation, and other electronic equipment found on ships. In a 1988 interview for the Smithsonian Institution, Olsen expressed the view that the Navy’s educa- tion programs did much to stimulate the growth of the U.S. electronics 2 industry. Many of the technicians trained by the Navy subsequently went Ken Olsen, circa 1965. to college and pursued careers in electronics. Olsen himself went to the (Photo courtesy of Ken H.Olsen) Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1947, where he studied electrical engineering, receiving his B.S. and M.S. MIT and Lincoln Laboratory At MIT, Olsen joined a group of engineers working under Jay Forrester on the Whirlwind computer.