Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 71, 1951

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

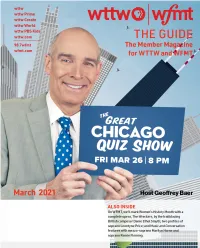

Geoffrey Baer, Who Each Friday Night Will Welcome Local Contestants Whose Knowledge of Trivia About Our City Will Be Put to the Test

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine Dear Member, for WTTW and WFMT This month, WTTW is excited to premiere a new series for Chicago trivia buffs and Renée Crown Public Media Center curious explorers alike. On March 26, join us for The Great Chicago Quiz Show hosted by 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60625 WTTW’s Geoffrey Baer, who each Friday night will welcome local contestants whose knowledge of trivia about our city will be put to the test. And on premiere night and after, visit Main Switchboard (773) 583-5000 wttw.com/quiz where you can play along at home. Turn to Member and Viewer Services page 4 for a behind-the-scenes interview with Geoffrey and (773) 509-1111 x 6 producer Eddie Griffin. We’ll also mark Women’s History Month with American Websites wttw.com Masters profiles of novelist Flannery O’Connor and wfmt.com choreographer Twyla Tharp; a POV documentary, And She Could Be Next, that explores a defiant movement of women of Publisher color transforming politics; and Not Done: Women Remaking Anne Gleason America, tracing the last five years of women’s fight for Art Director Tom Peth equality. On wttw.com, other Women’s History Month subjects include Emily Taft Douglas, WTTW Contributors a pioneering female Illinois politician, actress, and wife of Senator Paul Douglas who served Julia Maish in the U.S. House of Representatives; the past and present of Chicago’s Women’s Park and Lisa Tipton WFMT Contributors Gardens, designed by a team of female architects and featuring a statue by Louise Bourgeois; Andrea Lamoreaux and restaurateur Niquenya Collins and her newly launched Afro-Caribbean restaurant and catering business, Cocoa Chili. -

Scholarly Program Notes for the Graduate Voice Recital of Laura Neal Laura Neal [email protected]

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School 2012 Scholarly Program Notes for the Graduate Voice Recital of Laura Neal Laura Neal [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp I am not submitting this version as a PDF. Please let me know if there are any problems in the automatic conversion. Thank you! Recommended Citation Neal, Laura, "Scholarly Program Notes for the Graduate Voice Recital of Laura Neal" (2012). Research Papers. Paper 280. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp/280 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SCHOLARLY PROGRAM NOTES FOR MY GRADUATE VOCAL RECITAL by Laura S. Neal B.S., Murray State University, 2010 B.A., Murray State University, 2010 A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Masters in Music Department of Music in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2012 RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL SCHOLARLY PROGRAM NOTES ON MY GRADUATE VOCAL RECITAL By Laura Stone Neal A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters in the field of Music Approved by: Dr. Jeanine Wagner, Chair Dr. Diane Coloton Dr. Paul Transue Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 4, 2012 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank first and foremost my voice teacher and mentor, Dr. Jeanine Wagner for her constant support during my academic studies at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. -

!I M~Cy ~E~D~N~

Donald F. Cook Recital Hall M.O. Morgan Building Sunday, 27 October, 1996 at 8:00p.m. SCHOOL Rosemarie Landry, soprano OF MUSIC Dalton Baldwin, piano L' origine de Ia harpe Hector Berlioz Villanelle (1803-1869) L'Absent Charles Gounod Serenade (1818-1893) Romance de Mignon Henri Duparc Chanson Triste (1848-1933) Serenade italienne Ernest Chausson (1855-1899) Les cigales Emmanuel Chabrier Romance de 1'etoile (1841-1894) INTEllUdiSSION Chanson d' avril Georges Bizet (1838-1875) Psyche Emile Paladilhe (1844-1926) Ouvre tes yeux bleus Jules Massenet (1842-1912) Au bade Gabriel Faure En sourdine (1845-1924) Musique Claude Debussy Apparition (1862-1918) Les Filles de Cadix Uo Delibes (1836-1891) !iM~ cy~~E~d~n~ 048-036-09-96-1 5.000 Rosmarie Landry is one of the world's leading interpreters of French art song. She is an especially apt recipient of an honorary degree this year, since 1996 marks the 20th anniversary of the admission of students to Memorial's School of Music. Dr. Landry was born in Timmins, Ontario, in 1946, but was raised in Caraquet, NB. Proud of her Acadian ancestry, she has toured the world as an ambassador of Acadian culture since winning the voice category of the CBC Talent Festival in 1976. One of Canada's most renowned and accomplished sopranos, she is at home performing in solo recitals, with chamber musicians, and orchestras. She has sung with most of Canada's principal orchestras, choirs and opera companies, and has performed for radio and television. Dr. Landry has also performed with Orchestre Radio-France, the Singapore Symphony Orchestra and Orchestra Musicum Collegium of Geneva. -

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Zell Music Director Riccardo Muti Conductor Xavier De Maistre Harp Chabrier España

PROGRAM ONE HUNDRED TWENTY-FIFTH SEASON Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Zell Music Director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor Emeritus Yo-Yo Ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Tuesday, September 29, 2015, at 7:30 Riccardo Muti Conductor Xavier de Maistre Harp Chabrier España Ginastera Harp Concerto, Op. 25 Allegro giusto Molto moderato Liberamente capriccioso—Vivace XAVIER DE MAISTRE INTERMISSION Charpentier Impressions of Italy Serenade At the Fountain On Muleback On the Summits Napoli Ravel Boléro CSO Tuesday series concerts are sponsored by United Airlines. This work is part of the CSO Premiere Retrospective, which is generously sponsored by the Sargent Family Foundation. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. COMMENTS by Phillip Huscher Emmanuel Chabrier Born January 18, 1841, Ambert, France. Died September 13, 1894, Paris, France. España España is the sole survivor several of his canvases, including his last major of a once-prestigious work, the celebrated Bar aux Folies-Bergère, career. The only work by which he hung over his piano. (At the time of his Emmanuel Chabrier that death in 1894, Chabrier owned a small museum’s is still performed with any worth of significant art, including seven oils by regularity, it began as a Manet, six by Monet, three by Renoir, and one simple souvenir of six by Cézanne.) months in Spain. Although Chabrier dabbled in composition Chabrier and his wife from childhood and became a pianist of impres- spent the latter half of sive virtuosity, at first he followed the family tra- 1882 traveling the country, stopping in Toledo, dition and pursued law as his profession. -

Record Series 1121-105.4, W. W. Law Music Collection-Compact Discs, Inventory by Genre

Record Series 1121-105.4, W. W. Law Music Collection-Compact Discs, Inventory by Genre Genre Album title Contributor (s) Date Final Box # Item # Additional Notes Original CD Blues (music) James Cotton Living the Blues James Cotton; Larry McCray; John Primer; Johnny B. Gayden; Brian Jones; Dr. John; Lucky Peterson; Joe Louis Walker 1994 1121-105-242 19 Blues (music) Willie Dixon Willie Dixon; Andy McKaie; Don Snowden 1988 1121-105-249 01 Oversized case; 2 CD box set Blues (music) Cincinnati Blues (1928-1936) Bob Coleman's Cincinnati Jug Band and Associates; Walter Coleman; Bob Coleman no date 1121-105-242 17 Found with CD album in Box #10, Item #28; Case was found separately Blues (music) Willie Dixon, The Big Three Trio Willie Dixon; The Big Three Trio 1990 1121-105-242 18 Blues (music) The Best of Muddy Waters Muddy Waters 1987 1121-105-242 08 Blues (music) The Roots of Robert Johnson Robert Johnson 1990 1121-105-242 07 Blues (music) The Best of Mississippi John Hurt Mississippi John Hurt; Bob Scherl 1987 1121-105-242 06 Blues (music) Bud Powell: Blues for Bouffemont Bud Powell; Alan Bates 1989 1121-105-242 36 Friday, May 11, 2018 Page 1 of 89 Genre Album title Contributor (s) Date Final Box # Item # Additional Notes Original CD Blues (music) Big Bill Broonzy Good Time Tonight Big Bill Broonzy 1990 1121-105-242 04 Blues (music) Bessie Smith The Collection Bessie Smith; John Hammond; Frank Walker 1989 1121-105-242 38 Blues (music) Blind Willie Johnson Praise God I'm Satisfied Blind Willie Johnson 1989 1121-105-242 20 Post-it note was found on the back of this CD case, photocopy made and placed in envelope behind CD. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: FRENCH CHARACTER PIECES

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: FRENCH CHARACTER PIECES (1860-1960) Cindy Lin, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2013 Dissertation directed by: Professor Bradford Gowen School of Music My dissertation recording project explores a variety of musical works that realize the expressive and organizational potential of a highly coloristic approach to composition. I focus on French character pieces written between 1860 and 1960. Although numerous French character pieces were written before 1860 and after 1960, I have narrowed the scope of the list to the time range of a century. In this research, I analyze some of the works of ten composers in chronological order to show the subtle changes in style over time. The micro-level expressive qualities of these pieces as well as their macro-level organizational structures are analyzed in this document. The sources for the selected works include: 48 Esquisses, Op. 63 by Charles- Valentin Alkan; Dix piѐces pittoresques by Emmanuel Chabrier; Etudes de Concert, Op. 35 and Romances sans paroles, Op. 76 by Cécile Chaminade; Préludes (Book I and II) and Estampes by Claude Debussy; Miroirs by Maurice Ravel; Cerdaña by Déodat de Séverac; Les Heures persanes, Op. 65 by Charles Koechlin; Napoli Suite by Francis Poulenc; La Muse ménagѐre, Op. 245 by Darius Milhaud; and Préludes and Vingt Regards sur l’Enfant Jésus by Olivier Messiaen. I have recorded approximately two hours of solo piano music. The selected pieces were recorded on a Steinway “D” in Martha-Ellen Tye Recital Hall at Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa by Peter Nothnagle. This document is available in the digital Repository at the University of Maryland and the CD’s are available through the Library System at the University of Maryland. -

Kimberly Barber--Mezzo-Soprano

KIMBERLY BARBER, MEZZO-SOPRANO COMPLETE PERFORMANCE ARCHIVE Operatic and concert performances: 2019 “I never saw another butterfly: Music of the Holocaust”; Recital with Pianist Anna Ronai and Flutist Ulrike Anton; Richmond Hill Centre for the Performing Arts, Richmond Hill, ON, November 7, 2019 Gala Concert: Opening of CASP Conference; Edmonton, AB; mezzo-soprano Elizabeth Turnbull and others; October 16, 2019 Faculty Showcase: Music at Noon; Pianist Anna Ronai, Penderecki String Quartet, Pianists Anya Alexeyev and Glen Carruthers, vocalist Glenn Buhr; Maureen Forrester Recital Hall, Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, ON; September 12, 2019 Mysterious Barricades: The Stories We Tell; Kitchener Public Library Theatre, Kitchener, ON; Pianist Anna Ronai, Penderecki String Quartet, Trumpeter Guy Few and others; Sept 10, 2019 (coast-to-coast livestream Sept. 14-21, 2019) Closing concert Festival de Fourvière; Chateau LaCroix-Laval, Lyon, France; Pianists Franck Avitabile and Catherine Garonne, cellist Yannick Callier; Aug 4, 2019 Opening concert Festival de Fourvière; Hôtel de Ville, Lyon, France; Three Songs of James Joyce, op. 10, Samuel Barber; Pianist Laetitia Bougnol; Aug 1, 2019 Concert Lyrique, NSVI, Église Ste-Claire, Riviere-Beaudette, QC; Pianist Michael Shannon, Mezzo-soprano Maria Soulis and others; July 3, 2019 Église Ste-Madeleine, Rigaud, QC, July 6, 2019 Mme. de la Haltière, Cendrillon, Jules Massenet; Conductor Leslie De’Ath, Soprano Emily Vondrejs, Mezzo-soprano Dominie Boutin and others; Theatre Auditorium WLU, Waterloo, -

Scholarly Program Notes on the Graduate Voice Recital of Michelle Ford Michelle R

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Spring 2016 Scholarly Program Notes on the Graduate Voice Recital of Michelle Ford Michelle R. Ford Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation Ford, Michelle R. "Scholarly Program Notes on the Graduate Voice Recital of Michelle Ford." (Spring 2016). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SCHOLARLY PROGRAM NOTES ON THE GRADUATE VOICE RECITAL OF MICHELLE FORD by Michelle Ford (Degrees Earned) B.M., Murray State University, 2012 M.S., Institution, Year (CENTER EACH LINE) A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Music Department of Music in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2016 RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL SCHOLARLY PROGRAM NOTES ON THE GRADUATE VOICE RECITAL OF MICHELLE FORD By Michelle Ford A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music in the field of Music Approved by: Dr. David Dillard, Chair Prof. Tim Fink Cody Walker (Name of committee member 3) (Name of committee member 4) Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale April 11, 2016 AN ABSTRACT OF THE RESEARCH PAPER OF MICHELLE FORD, for the Master of Music degree in MUSIC, presented on APRIL 11, 2016, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: SCHOLARLY PROGRAM NOTES ON THE GRADUATE VOICE RECITAL OF MICHELLE FORD MAJOR PROFESSOR: Dr. -

Emmanuel Chabrier Et Moi 79 Daniel Jacobson 27 a Conversation with Nicolas Le Riche

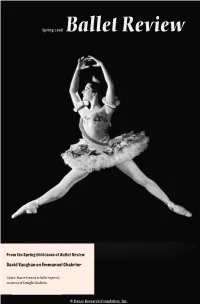

Spring 2008 Ball et Revi ew From the Spring 2008 issue of Ballet Review David Vaughan on Emmanuel Chabrier Cover: Marie-Jeanne in Ballet Imperial , courtesy of Dwight Godwin. © Dance Research Foundation, Inc. 4 Amsterdam – Clement Crisp 5 Chicago – Joseph Houseal 6 Toronto – Gary Smith 7 Oakland – Leigh Witchel 8 St. Petersburg, Etc. – Kevin Ng 10 Hamilton – Gary Smith 11 London – Joseph Houseal 13 San Francisco – Leigh Witchel 15 Toronto – Gary Smith David Vaughan 17 Emmanuel Chabrier et Moi 79 Daniel Jacobson 27 A Conversation with Nicolas Le Riche Joseph Houseal 39 Lucinda Childs: Counting Out the Bomb Photographs by Costas 43 Robbins Onstage Edited by Francis Mason 43 Nina Alovert Ballet Review 36.1 50 A Conversation with Spring 2008 Vladimir Kekhman Associate Editor and Designer: Joseph Houseal Marvin Hoshino 53 Tragedy and Transcendence Associate Editor: Don Daniels Davie Lerner 59 Marie-Jeanne Assistant Editor: Joel Lobenthal Marilyn Hunt 39 Photographers: 74 ABT: Autumn in New York Tom Brazil Costas Sandra Genter Subscriptions: 79 Next Wave XXV Roberta Hellman Copy Editor: Elizabeth Kattner Barbara Palfy 88 Marche Funèbre , A Lost Work Associates: of Balanchine Peter Anastos Robert Gres kovic 94 Music on Disc – George Dorris George Jackson 27 100 Check It Out Elizabeth Kendall Paul Parish Nancy Reynolds James Sutton David Vaughan Edward Willinger Sarah C. Woodcock Cover: Marie-Jeanne in Ballet Imperial , courtesy of Dwight Godwin. Emmanuel Chabrier he is thought by many to be the link between eighteenth-century French compos ers such et Moi as Rameau and Couperin, and later ones like Debussy and Ravel, both of whom revered his music, as did Erik Satie, Reynaldo Hahn, and David Vaughan Francis Poulenc (who wrote a book about him). -

Emmanuel Chabrier, Une Biographie De Francis Poulenc Michel Burgard

Emmanuel Chabrier, une biographie de Francis Poulenc Michel Burgard À la mémoire du Professeur François Roth, notre confrère, notre ami. Quand on apprécie les surprises routières, il est un endroit où l’on ne peut pas être déçu. Partez de Montbrison, Loire, ville natale de Pierre Boulez, et rendez vous à Ambert, Puy-de-Dôme, célèbre pour sa ronde mairie, celle autour de laquelle tournent Les Copains de Jules Romains et pour son compositeur, Emmanuel Chabrier. Quand il écrit son petit ouvrage, publié à La Palatine en 1961, Françis Poulenc ne tient pas à « faire de la musicologie » : Olivier Messiaen aurait dit : « Je ne suis pas ornithologue, je suis oiseau ». Poulenc aurait pu dire : « Je ne suis pas musicologue, je suis musicien ». Ricardo Viñes, son maître, et Marcelle Meyer, pianistes, « inoubliables interprètes de Chabrier », en reçoivent la dédicace. Le but de son écrit ? D’une haute ambition ! « Faire aimer autant qu’admirer ce musicien de première grandeur. » Ses pairs ? Debussy, Ravel, logiquement, Satie. L’école d’Arcueil jouxte le groupe des Six. Plus surprenant, Gabriel Fauré. Le portrait qu’il trace, d’une plume pittoresque, use de termes auvergnats : « bougnat » « foutrauds », entendez « originaux ». Il souligne aussi le contraste entre le négligé de la caricature de Detaille et le portrait soigné du fonctionnaire de la toile du Louvre, Chabrier travaillant alors, après sa licence en droit, au bureau des ampliations ( !) du ministère de l’Intérieur. Ami personnel de Monet, Manet, Renoir, Sisley, dont il possédait des toiles, il n’a jamais établi de correspondances entre peinture et musique dans son œuvre. -

Philippe Jaroussky, Countertenor Jérôme Ducros, Piano

Thursday, May 12, 2016, 8pm First Congregational Church Philippe Jaroussky, countertenor Jérôme Ducros, piano PROGRAM Gabriel FAURÉ (1845–1924) Clair de lune Green Reynaldo HAHN (1874–1947) En sourdine POLDOWSKI (1879–1932) Colombine Charles BORDES (1863–1909) Ô triste, triste était mon âme Claude DEBUSSY (1862–1918) Prélude from Suite bergamasque FAURÉ Mandoline PROGRAM Déodat DE SÉVERAC (1872–1921) Prison (Le ciel est, par-dessus le toit) Ernest CHAUSSON (1855–1899) La chanson bien douce POLDOWSKI Mandoline L’Heure exquise ( La lune blanche) Emmanuel CHABRIER (1841–1894) Idylle from Pièces pittoresques HAHN D’une prison (Le ciel est, par-dessus le toit) DEBUSSY Fêtes galantes I, FL. 86 (En sourdine – Fantoches – Clair de lune) Léo FERRÉ (1916–1993) Écoutez la chanson bien douce INTERMISSION Józef Zygmunt SZULC (1875–1956) Clair de lune André CAPLET (1878–1925) Green HAHN Chanson d’automne Camille SAINT-SAëNS (1935–1921) Le vent dans la plaine (C’est l’extase langoureuse) FERRÉ Colloque sentimental DEBUSSY “Clair de lune” from Suite bergamasque FAURÉ C’est l’extase CHAUSSON Apaisement (La lune blanche) DEBUSSY Mandoline Arthur HONEGGER (1892–1955) Un grand sommeil noir DEBUSSY L’Isle joyeuse Fêtes galantes II, FL. 114 (Les Ingénus – Le Faune – Colloque sentimental) Charles TRENET (1913–2001) Verlaine (Chanson d’automne) Funded, in part, by the Koret Foundation, this performance is part of Cal Performances’ 2015–2016 Koret Recital Series, which brings world-class artists to our community. Additional support provided by Patron Sponsor Françoise Stone. Cal Performances' 2015-2016 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. PLAYBILL PROGRAM NOTES Why should a countertenor not have the nec - music, perhaps because his poetry creates a vi - essary sensitivity and vocal technique to per - sual rather than an aural world). -

VERMONT YOUTH ORCHESTRA in Its Forty-Sixth Season Troy Peters, Music Director and Conductor

VERMONT YOUTH ORCHESTRA in its forty-sixth season Troy Peters, Music Director and Conductor Friday, September 26, 2008 Sunday, September 28, 2008 8:00 p.m. 3:00 p.m. Harwood Union High School The Flynn Center for the Performing Moretown, Vermont Arts Burlington, Vermont PROGRAM “Vive la France” Emmanuel Chabrier Joyeuse marche François Borne Carmen Fantasy (orchestrated by Raymond Meylan) Kelly Herrmann, flute Claude Debussy “Festivals” from Nocturnes Maurice Ravel Concerto in G major for Piano and Orchestra I. Allegramente Samantha Angstman, piano INTERMISSION Camille Saint-Saëns Bacchanal from Samson and Delilah, Op. 47 Alexander Borodin Symphony No. 2 in B minor Allegro Scherzo: Prestissimo Andante — Finale: Allegro PROGRAM NOTES by Troy Peters Chabrier: Joyeuse marche Although he displayed great musical promise as a child, Emmanuel Chabrier (1841-1894) became a civil servant in France’s Ministry of the Interior. Working in Paris, he befriended leading musicians and painters of the time, including Manet (who painted Chabrier’s portrait twice). Seeing Wagner’s opera, Tristan and Isolde, on an 1880 trip to Germany so inspired Chabrier that he decided to quit his job and devote his life to music. Like much of Chabrier’s music, Joyeuse marche (“Joyful March”) was written for piano and later orchestrated by the composer. He conducted its premiere to open an 1888 festival devoted to his music at Angers in the Loire valley. The march was a hit, and the festival ended up being a highpoint of Chabrier’s brief career, as he was just beginning to struggle with the mental illness that would soon make him unable to compose.