PROGRAM NOTES by Daniel Maki

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Samba, Rumba, Cha-Cha, Salsa, Merengue, Cumbia, Flamenco, Tango, Bolero

SAMBA, RUMBA, CHA-CHA, SALSA, MERENGUE, CUMBIA, FLAMENCO, TANGO, BOLERO PROMOTIONAL MATERIAL DAVID GIARDINA Guitarist / Manager 860.568.1172 [email protected] www.gozaband.com ABOUT GOZA We are pleased to present to you GOZA - an engaging Latin/Latin Jazz musical ensemble comprised of Connecticut’s most seasoned and versatile musicians. GOZA (Spanish for Joy) performs exciting music and dance rhythms from Latin America, Brazil and Spain with guitar, violin, horns, Latin percussion and beautiful, romantic vocals. Goza rhythms include: samba, rumba cha-cha, salsa, cumbia, flamenco, tango, and bolero and num- bers by Jobim, Tito Puente, Gipsy Kings, Buena Vista, Rollins and Dizzy. We also have many originals and arrangements of Beatles, Santana, Stevie Wonder, Van Morrison, Guns & Roses and Rodrigo y Gabriela. Click here for repertoire. Goza has performed multiple times at the Mohegan Sun Wolfden, Hartford Wadsworth Atheneum, Elizabeth Park in West Hartford, River Camelot Cruises, festivals, colleges, libraries and clubs throughout New England. They are listed with many top agencies including James Daniels, Soloman, East West, Landerman, Pyramid, Cutting Edge and have played hundreds of weddings and similar functions. Regular performances in the Hartford area include venues such as: Casona, Chango Rosa, La Tavola Ristorante, Arthur Murray Dance Studio and Elizabeth Park. For more information about GOZA and for our performance schedule, please visit our website at www.gozaband.com or call David Giardina at 860.568-1172. We look forward -

The Global Reach of the Fandango in Music, Song and Dance

The Global Reach of the Fandango in Music, Song and Dance The Global Reach of the Fandango in Music, Song and Dance: Spaniards, Indians, Africans and Gypsies Edited by K. Meira Goldberg and Antoni Pizà The Global Reach of the Fandango in Music, Song and Dance: Spaniards, Indians, Africans and Gypsies Edited by K. Meira Goldberg and Antoni Pizà This book first published 2016 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2016 by K. Meira Goldberg, Antoni Pizà and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-9963-1 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-9963-5 Proceedings from the international conference organized and held at THE FOUNDATION FOR IBERIAN MUSIC, The Graduate Center, The City University of New York, on April 17 and 18, 2015 This volume is a revised and translated edition of bilingual conference proceedings published by the Junta de Andalucía, Consejería de Cultura: Centro de Documentación Musical de Andalucía, Música Oral del Sur, vol. 12 (2015). The bilingual proceedings may be accessed here: http://www.centrodedocumentacionmusicaldeandalucia.es/opencms/do cumentacion/revistas/revistas-mos/musica-oral-del-sur-n12.html Frontispiece images: David Durán Barrera, of the group Los Jilguerillos del Huerto, Huetamo, (Michoacán), June 11, 2011. -

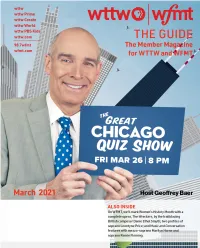

Geoffrey Baer, Who Each Friday Night Will Welcome Local Contestants Whose Knowledge of Trivia About Our City Will Be Put to the Test

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine Dear Member, for WTTW and WFMT This month, WTTW is excited to premiere a new series for Chicago trivia buffs and Renée Crown Public Media Center curious explorers alike. On March 26, join us for The Great Chicago Quiz Show hosted by 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60625 WTTW’s Geoffrey Baer, who each Friday night will welcome local contestants whose knowledge of trivia about our city will be put to the test. And on premiere night and after, visit Main Switchboard (773) 583-5000 wttw.com/quiz where you can play along at home. Turn to Member and Viewer Services page 4 for a behind-the-scenes interview with Geoffrey and (773) 509-1111 x 6 producer Eddie Griffin. We’ll also mark Women’s History Month with American Websites wttw.com Masters profiles of novelist Flannery O’Connor and wfmt.com choreographer Twyla Tharp; a POV documentary, And She Could Be Next, that explores a defiant movement of women of Publisher color transforming politics; and Not Done: Women Remaking Anne Gleason America, tracing the last five years of women’s fight for Art Director Tom Peth equality. On wttw.com, other Women’s History Month subjects include Emily Taft Douglas, WTTW Contributors a pioneering female Illinois politician, actress, and wife of Senator Paul Douglas who served Julia Maish in the U.S. House of Representatives; the past and present of Chicago’s Women’s Park and Lisa Tipton WFMT Contributors Gardens, designed by a team of female architects and featuring a statue by Louise Bourgeois; Andrea Lamoreaux and restaurateur Niquenya Collins and her newly launched Afro-Caribbean restaurant and catering business, Cocoa Chili. -

Scholarly Program Notes for the Graduate Voice Recital of Laura Neal Laura Neal [email protected]

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School 2012 Scholarly Program Notes for the Graduate Voice Recital of Laura Neal Laura Neal [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp I am not submitting this version as a PDF. Please let me know if there are any problems in the automatic conversion. Thank you! Recommended Citation Neal, Laura, "Scholarly Program Notes for the Graduate Voice Recital of Laura Neal" (2012). Research Papers. Paper 280. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp/280 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SCHOLARLY PROGRAM NOTES FOR MY GRADUATE VOCAL RECITAL by Laura S. Neal B.S., Murray State University, 2010 B.A., Murray State University, 2010 A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Masters in Music Department of Music in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2012 RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL SCHOLARLY PROGRAM NOTES ON MY GRADUATE VOCAL RECITAL By Laura Stone Neal A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters in the field of Music Approved by: Dr. Jeanine Wagner, Chair Dr. Diane Coloton Dr. Paul Transue Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 4, 2012 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank first and foremost my voice teacher and mentor, Dr. Jeanine Wagner for her constant support during my academic studies at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. -

!I M~Cy ~E~D~N~

Donald F. Cook Recital Hall M.O. Morgan Building Sunday, 27 October, 1996 at 8:00p.m. SCHOOL Rosemarie Landry, soprano OF MUSIC Dalton Baldwin, piano L' origine de Ia harpe Hector Berlioz Villanelle (1803-1869) L'Absent Charles Gounod Serenade (1818-1893) Romance de Mignon Henri Duparc Chanson Triste (1848-1933) Serenade italienne Ernest Chausson (1855-1899) Les cigales Emmanuel Chabrier Romance de 1'etoile (1841-1894) INTEllUdiSSION Chanson d' avril Georges Bizet (1838-1875) Psyche Emile Paladilhe (1844-1926) Ouvre tes yeux bleus Jules Massenet (1842-1912) Au bade Gabriel Faure En sourdine (1845-1924) Musique Claude Debussy Apparition (1862-1918) Les Filles de Cadix Uo Delibes (1836-1891) !iM~ cy~~E~d~n~ 048-036-09-96-1 5.000 Rosmarie Landry is one of the world's leading interpreters of French art song. She is an especially apt recipient of an honorary degree this year, since 1996 marks the 20th anniversary of the admission of students to Memorial's School of Music. Dr. Landry was born in Timmins, Ontario, in 1946, but was raised in Caraquet, NB. Proud of her Acadian ancestry, she has toured the world as an ambassador of Acadian culture since winning the voice category of the CBC Talent Festival in 1976. One of Canada's most renowned and accomplished sopranos, she is at home performing in solo recitals, with chamber musicians, and orchestras. She has sung with most of Canada's principal orchestras, choirs and opera companies, and has performed for radio and television. Dr. Landry has also performed with Orchestre Radio-France, the Singapore Symphony Orchestra and Orchestra Musicum Collegium of Geneva. -

Spanish Local Color in Bizet's Carmen.Pdf

!@14 QW Spanish Local Color in Bizet’s Carmen unexplored borrowings and transformations Ralph P. Locke Bizet’s greatest opera had a rough start in life. True, it was written and composed to meet many of the dramatic and musical expectations of opéra comique. It offered charming and colorful secondary characters that helped “place” the work in its cho- sen locale (such as the Spanish innkeeper Lillas Pastia and Carmen’s various Gypsy sidekicks, female and male), simple strophic forms in many musical numbers, and extensive spoken dialogue between the musical numbers.1 Despite all of this, the work I am grateful for many insightful suggestions from Philip Gossett and Roger Parker and from early readers of this paper—notably Steven Huebner, David Rosen, Lesley A. Wright, and Hervé Lacombe. I also benefi ted from the suggestions of three specialists in the music of Spain: Michael Christoforidis, Suzanne Rhodes Draayer (who kindly provided a photocopy of the sheet-music cover featuring Zélia Trebelli), and—for generously sharing his trove of Garciana, including photocopies of the autograph vocal and instrumental parts for “Cuerpo bueno” that survive in Madrid—James Radomski. The Bibliothèque nationale de France kindly provided microfi lms of their two manu- scripts of “Cuerpo bueno” (formerly in the library of the Paris Conservatoire). Certain points in the present paper were fi rst aired briefl y in one section of a wider-ranging essay, “Nineteenth-Century Music: Quantity, Quality, Qualities,” Nineteenth-Century Music Review 1 (2004): 3–41, at 30–37. In that essay I erroneously referred in passing to Bizet’s piano-vocal score as having been published by Heugel; the publisher was, of course, Choudens. -

Andalucía Flamenca: Music, Regionalism and Identity in Southern Spain

Andalucía flamenca: Music, Regionalism and Identity in Southern Spain A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Matthew Machin-Autenrieth © Matthew Machin-Autenrieth 2013 Tables of Contents Table of Contents i List of Plates iv List of Examples iv List of Figures v Conventions vi Acknowledgments viii Abstract x Introduction 1 PART ONE Chapter One: An Overview of Flamenco 6 The Identities of Flamenco 9 The Materials of Flamenco 12 The Geographies of Flamenco 19 The Scholars of Flamenco 25 Chapter Two: Music, Regionalism and Political Geography 36 Political Geography and Music 37 Region, Regionalisation and Regionalism 43 Regionalism and Music 51 The Theoretical Framework 61 Conclusions 68 Chapter Three: Methodology 70 Virtual Ethnography: In Theory 70 Virtual Ethnography: In Practice 79 Field Research in Granada 86 Conclusions 97 Chapter Four: Regionalism, Nationalism and Ethnicity in the History of Flamenco 98 Flamenco and the Emergence of Andalucismo (1800s–1900s) 99 Flamenco and the Nation: Commercialisation, Salvation and Antiflamenquismo 113 Flamenco and Political Andalucismo (1900–1936) 117 Flamenco during the Franco Regime (1939–75) 122 Flamenco since the Transition to Democracy (1975 onwards) 127 Conclusions 131 i Chapter Five: Flamenco for Andalusia, Flamenco for Humanity 133 Flamenco for Andalusia: The Statute of Autonomy 134 Flamenco for Humanity: Intangible Cultural Heritage 141 The Regionalisation of Flamenco in Andalusia 152 Conclusions 169 PART -

Bambuco, Tango and Bolero: Music, Identity, and Class Struggles in Medell´In, Colombia, 1930–1953

BAMBUCO, TANGO AND BOLERO: MUSIC, IDENTITY, AND CLASS STRUGGLES IN MEDELL¶IN, COLOMBIA, 1930{1953 by Carolina Santamar¶³aDelgado B.S. in Music (harpsichord), Ponti¯cia Universidad Javeriana, 1997 M.A. in Ethnomusicology, University of Pittsburgh, 2002 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Department of Music in partial ful¯llment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of Pittsburgh 2006 BAMBUCO, TANGO AND BOLERO: MUSIC, IDENTITY, AND CLASS STRUGGLES IN MEDELL¶IN, COLOMBIA, 1930{1953 Carolina Santamar¶³aDelgado, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2006 This dissertation explores the articulation of music, identity, and class struggles in the pro- duction, reception, and consumption of sound recordings of popular music in Colombia, 1930- 1953. I analyze practices of cultural consumption involving records in Medell¶³n,Colombia's second largest city and most important industrial center at the time. The study sheds light on some of the complex connections between two simultaneous historical processes during the mid-twentieth century, mass consumption and socio-political strife. Between 1930 and 1953, Colombian society experienced the rise of mass media and mass consumption as well as the outbreak of La Violencia, a turbulent period of social and political strife. Through an analysis of written material, especially the popular press, this work illustrates the use of aesthetic judgments to establish social di®erences in terms of ethnicity, social class, and gender. Another important aspect of the dissertation focuses on the adoption of music gen- res by di®erent groups, not only to demarcate di®erences at the local level, but as a means to inscribe these groups within larger imagined communities. -

Aragón and Valencia

ARAGÓN AND VALÈNCIA Aragón and València “The jota is at its best with the scent of rosemary and fresh-plowed earth,” says the opening song on this CD. An infectious collection of danced and sung jotas, archaic threshing songs, May courting songs, struck zither tunes, raucous shawms and lyrical strings, travelling down from the mountains of Aragón to the fertile coast of València. The Spanish Recordings Alan Lomax made these historic recordings in 1952 while traveling for months through Spanish villages, under formidable physical and political circumstances, during the Franco regime. Covering the breadth of Spain, these songs and dance melodies constitute a portrait of rural Spain’s richly varied musical life, dispelling the common stereotypes of Spanish folk music. The Alan Lomax Collection The Alan Lomax Collection gathers together the American, European, and Caribbean field recordings, world music compilations, and ballad operas of writer, folklorist, and ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax. Recorded in 1952 by Alan Lomax. Introductions and notes by Luis Bajén García and Mario Gros Herrero (Aragón), Archivo de Tradición Oral de Aragón (ATOA); and Josemi Sánchez Velasco (València), Consellería de Cultura, Educació i Ciència, Generalitat de València. Series Editor, Judith R. Cohen, Ph.D. Remastered to 24-bit digital from the original field recordings. Contains previously unreleased recordings. Aragón 1. AL REGRESO DEL CAMPO (Work jota) Teruel (2:19) 2. A LAS ORILLAS DEL RÍO (Danced jota) Teruel (2:30) 3. JOTA HURTADA (“Stolen” jota) Albarracín (1:08) 4. MAYOS DE ALBARRACÍN (May courting verses) Albarracín (2:53) 5. SE ME OLVIDAN LOS RAMALES (Jota for plowing) Monreal del Campo (0:50) 6. -

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Zell Music Director Riccardo Muti Conductor Xavier De Maistre Harp Chabrier España

PROGRAM ONE HUNDRED TWENTY-FIFTH SEASON Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Zell Music Director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor Emeritus Yo-Yo Ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Tuesday, September 29, 2015, at 7:30 Riccardo Muti Conductor Xavier de Maistre Harp Chabrier España Ginastera Harp Concerto, Op. 25 Allegro giusto Molto moderato Liberamente capriccioso—Vivace XAVIER DE MAISTRE INTERMISSION Charpentier Impressions of Italy Serenade At the Fountain On Muleback On the Summits Napoli Ravel Boléro CSO Tuesday series concerts are sponsored by United Airlines. This work is part of the CSO Premiere Retrospective, which is generously sponsored by the Sargent Family Foundation. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. COMMENTS by Phillip Huscher Emmanuel Chabrier Born January 18, 1841, Ambert, France. Died September 13, 1894, Paris, France. España España is the sole survivor several of his canvases, including his last major of a once-prestigious work, the celebrated Bar aux Folies-Bergère, career. The only work by which he hung over his piano. (At the time of his Emmanuel Chabrier that death in 1894, Chabrier owned a small museum’s is still performed with any worth of significant art, including seven oils by regularity, it began as a Manet, six by Monet, three by Renoir, and one simple souvenir of six by Cézanne.) months in Spain. Although Chabrier dabbled in composition Chabrier and his wife from childhood and became a pianist of impres- spent the latter half of sive virtuosity, at first he followed the family tra- 1882 traveling the country, stopping in Toledo, dition and pursued law as his profession. -

Violin Syllabus / 2013 Edition

VVioliniolin SYLLABUS / 2013 EDITION SYLLABUS EDITION © Copyright 2013 The Frederick Harris Music Co., Limited All Rights Reserved Message from the President The Royal Conservatory of Music was founded in 1886 with the idea that a single institution could bind the people of a nation together with the common thread of shared musical experience. More than a century later, we continue to build and expand on this vision. Today, The Royal Conservatory is recognized in communities across North America for outstanding service to students, teachers, and parents, as well as strict adherence to high academic standards through a variety of activities—teaching, examining, publishing, research, and community outreach. Our students and teachers benefit from a curriculum based on more than 125 years of commitment to the highest pedagogical objectives. The strength of the curriculum is reinforced by the distinguished College of Examiners—a group of fine musicians and teachers who have been carefully selected from across Canada, the United States, and abroad for their demonstrated skill and professionalism. A rigorous examiner apprenticeship program, combined with regular evaluation procedures, ensures consistency and an examination experience of the highest quality for candidates. As you pursue your studies or teach others, you become not only an important partner with The Royal Conservatory in the development of creativity, discipline, and goal- setting, but also an active participant, experiencing the transcendent qualities of music itself. In a society where our day-to-day lives can become rote and routine, the human need to find self-fulfillment and to engage in creative activity has never been more necessary. -

Record Series 1121-105.4, W. W. Law Music Collection-Compact Discs, Inventory by Genre

Record Series 1121-105.4, W. W. Law Music Collection-Compact Discs, Inventory by Genre Genre Album title Contributor (s) Date Final Box # Item # Additional Notes Original CD Blues (music) James Cotton Living the Blues James Cotton; Larry McCray; John Primer; Johnny B. Gayden; Brian Jones; Dr. John; Lucky Peterson; Joe Louis Walker 1994 1121-105-242 19 Blues (music) Willie Dixon Willie Dixon; Andy McKaie; Don Snowden 1988 1121-105-249 01 Oversized case; 2 CD box set Blues (music) Cincinnati Blues (1928-1936) Bob Coleman's Cincinnati Jug Band and Associates; Walter Coleman; Bob Coleman no date 1121-105-242 17 Found with CD album in Box #10, Item #28; Case was found separately Blues (music) Willie Dixon, The Big Three Trio Willie Dixon; The Big Three Trio 1990 1121-105-242 18 Blues (music) The Best of Muddy Waters Muddy Waters 1987 1121-105-242 08 Blues (music) The Roots of Robert Johnson Robert Johnson 1990 1121-105-242 07 Blues (music) The Best of Mississippi John Hurt Mississippi John Hurt; Bob Scherl 1987 1121-105-242 06 Blues (music) Bud Powell: Blues for Bouffemont Bud Powell; Alan Bates 1989 1121-105-242 36 Friday, May 11, 2018 Page 1 of 89 Genre Album title Contributor (s) Date Final Box # Item # Additional Notes Original CD Blues (music) Big Bill Broonzy Good Time Tonight Big Bill Broonzy 1990 1121-105-242 04 Blues (music) Bessie Smith The Collection Bessie Smith; John Hammond; Frank Walker 1989 1121-105-242 38 Blues (music) Blind Willie Johnson Praise God I'm Satisfied Blind Willie Johnson 1989 1121-105-242 20 Post-it note was found on the back of this CD case, photocopy made and placed in envelope behind CD.