Field Guide to Common Legume Species of the Longleaf Pine Ecosystem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eating a Low-Fiber Diet

Page 1 of 2 Eating a Low-fiber Diet What is fiber? Sample Menu Fiber is the part of food that the body cannot digest. Breakfast: It helps form stools (bowel movements). 1 scrambled egg 1 slice white toast with 1 teaspoon margarine If you eat less fiber, you may: ½ cup Cream of Wheat with sugar • Reduce belly pain, diarrhea (loose, watery stools) ½ cup milk and other digestive problems ½ cup pulp-free orange juice • Have fewer and smaller stools Snack: • Decrease inflammation (pain, redness and ½ cup canned fruit cocktail (in juice) swelling) in the GI (gastro-intestinal) tract 6 saltine crackers • Promote healing in the GI tract. Lunch: For a list of foods allowed in a low-fiber diet, see the Tuna sandwich on white bread back of this page. 1 cup cream of chicken soup ½ cup canned peaches (in light syrup) Why might I need a low-fiber diet? 1 cup lemonade You may need a low-fiber diet if you have: Snack: ½ cup cottage cheese • Inflamed bowels 1 medium apple, sliced and peeled • Crohn’s disease • Diverticular disease Dinner: 3 ounces well-cooked chicken breast • Ulcerative colitis 1 cup white rice • Radiation therapy to the belly area ½ cup cooked canned carrots • Chemotherapy 1 white dinner roll with 1 teaspoon margarine 1 slice angel food cake • An upcoming colonoscopy 1 cup herbal tea • Surgery on your intestines or in the belly area. For informational purposes only. Not to replace the advice of your health care provider. Copyright © 2007 Fairview Health Services. All rights reserved. Clinically reviewed by Shyamala Ganesh, Manager Clinical Nutrition. -

A Synopsis of Phaseoleae (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae) James Andrew Lackey Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1977 A synopsis of Phaseoleae (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae) James Andrew Lackey Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Lackey, James Andrew, "A synopsis of Phaseoleae (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae) " (1977). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 5832. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/5832 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Celiac Disease Resource Guide for a Gluten-Free Diet a Family Resource from the Celiac Disease Program

Celiac Disease Resource Guide for a Gluten-Free Diet A family resource from the Celiac Disease Program celiacdisease.stanfordchildrens.org What Is a Gluten-Free How Do I Diet? Get Started? A gluten-free diet is a diet that completely Your first instinct may be to stop at the excludes the protein gluten. Gluten is grocery store on your way home from made up of gliadin and glutelin which is the doctor’s office and search for all the found in grains including wheat, barley, gluten-free products you can find. While and rye. Gluten is found in any food or this initial fear may feel a bit overwhelming product made from these grains. These but the good news is you most likely gluten-containing grains are also frequently already have some gluten-free foods in used as fillers and flavoring agents and your pantry. are added to many processed foods, so it is critical to read the ingredient list on all food labels. Manufacturers often Use this guide to select appropriate meals change the ingredients in processed and snacks. Prepare your own gluten-free foods, so be sure to check the ingredient foods and stock your pantry. Many of your list every time you purchase a product. favorite brands may already be gluten-free. The FDA announced on August 2, 2013, that if a product bears the label “gluten-free,” the food must contain less than 20 ppm gluten, as well as meet other criteria. *The rule also applies to products labeled “no gluten,” “free of gluten,” and “without gluten.” The labeling of food products as “gluten- free” is a voluntary action for manufacturers. -

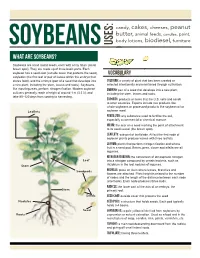

What Are Soybeans?

candy, cakes, cheeses, peanut butter, animal feeds, candles, paint, body lotions, biodiesel, furniture soybeans USES: What are soybeans? Soybeans are small round seeds, each with a tiny hilum (small brown spot). They are made up of three basic parts. Each soybean has a seed coat (outside cover that protects the seed), VOCABULARY cotyledon (the first leaf or pair of leaves within the embryo that stores food), and the embryo (part of a seed that develops into Cultivar: a variety of plant that has been created or a new plant, including the stem, leaves and roots). Soybeans, selected intentionally and maintained through cultivation. like most legumes, perform nitrogen fixation. Modern soybean Embryo: part of a seed that develops into a new plant, cultivars generally reach a height of around 1 m (3.3 ft), and including the stem, leaves and roots. take 80–120 days from sowing to harvesting. Exports: products or items that the U.S. sells and sends to other countries. Exports include raw products like whole soybeans or processed products like soybean oil or Leaflets soybean meal. Fertilizer: any substance used to fertilize the soil, especially a commercial or chemical manure. Hilum: the scar on a seed marking the point of attachment to its seed vessel (the brown spot). Leaflets: sub-part of leaf blade. All but the first node of soybean plants produce leaves with three leaflets. Legume: plants that perform nitrogen fixation and whose fruit is a seed pod. Beans, peas, clover and alfalfa are all legumes. Nitrogen Fixation: the conversion of atmospheric nitrogen Leaf into a nitrogen compound by certain bacteria, such as Stem rhizobium in the root nodules of legumes. -

Soy Free Diet Avoiding Soy

SOY FREE DIET AVOIDING SOY An allergy to soy is common in babies and young children, studies show that often children outgrow a soy allergy by age 3 years and the majority by age 10. Soybeans are a member of the legume family; examples of other legumes include beans, peas, lentils and peanut. It is important to remember that children with a soy allergy are not necessarily allergic to other legumes, request more clarification from your allergist if you are concerned. Children with a soy allergy may have nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, bloody stool, difficulty breathing, and or a skin reaction after eating or drinking soy products. These symptoms can be avoided by following a soy free diet. What foods are not allowed on a soy free diet? Soy beans and edamame Soy products, including tofu, miso, natto, soy sauce (including sho yu, tamari), soy milk/creamer/ice cream/yogurt, soy nuts and soy protein, tempeh, textured vegetable protein (TVP) Caution with processed foods - soy is widely used manufactured food products – remember to carefully read labels. o Soy products and derivatives can be found in many foods, including baked goods, canned tuna and meat, cereals, cookies, crackers, high-protein energy bars, drinks and snacks, infant formulas, low- fat peanut butter, processed meats, sauces, chips, canned broths and soups, condiments and salad dressings (Bragg’s Liquid Aminos) USE EXTRA CAUTION WITH ASIAN CUISINE: Asian cuisine are considered high-risk for people with soy allergy due to the common use of soy as an ingredient and the possibility of cross-contamination, even if a soy-free item is ordered. -

JJB 88 3 .Indd

J. Jpn. Bot. 88: 166–175 (2013) New Combinations in North American Desmodium (Leguminosae: Tribe Desmodieae) Hiroyoshi OHASHI Herbarium, Botanical Garden, Tohoku University, Sendai, 980-0862 JAPAN E-mail: [email protected] (Accepted on May 11, 2013) Three species groups in Desmodium of North America: D. ciliare group, D. paniculatum group and D. procumbens group are revised for Flora of North America. Each of them is treated as a single species containing one or two varieties. The following four new combinations are published: D. marilandicum var. ciliare (Willd.) H. Ohashi, D. marilandicum var. lancifolium (Fernald & B. G. Schub.) H. Ohashi, D. paniculatum var. fernaldii (B. G. Schub.) H. Ohashi, and D. procumbens var. neomexicanum (A. Gray) H. Ohashi. Desmodium obtusum (Willd.) DC. is regarded to be a synonym of D. marilandicum var. lancifolium; D. glabellum (Michx.) DC. and D. perplexum B.G. Schub. to be synonyms of D. paniculatum; and D. procumbens var. exiguum (A. Gray) B. G. Schub. to be a synonym of D. procumbens var. procumbens. Key words: Desmodium, Fabaceae, Leguminosae, new combinations, North America. Recently, Desmodium of North America can at least identify it with the group.” Under has been the subject of much study, notably by this framework, Isely recognized D. ciliare Schubert (1940, 1950a, 1950b, 1970) and Isely (Willd.) DC., D. paniculatum (L.) DC. and D. (1983, 1990, 1998). “Desmodium traditionally procumbens (Mill.) Hitchc., along with each is considered a ‘difficult’ genus” (Isely 1990, p. of their related taxa, as species groups. The 163). Isely (1990) further stated that Desmodium difficulty in classifying these groups is, however, contains “groups of species whose taxonomy not satisfactorily solved by this approach. -

Humnet's Top Hummingbird Plants for the Southeast

HumNet's Top Hummingbird Plants for the Southeast Votes Species Common Name Persistence US Native 27 Salvia spp. Salvia or Sage Perennial, annuals Yes - some species 8 Malvaviscus arboreus var. drummondii Turkscap Perennial Yes 8 Salvia gauranitica Anise Sage Perennial 6 Cuphea spp. Cuphea Perennial, annuals 5 Justicia brandegeana Shrimp Plant Tender Perennial 5 Salvia coccinea Scarlet Sage, Texas Sage Annual - reseeds Yes 5 Stachytarpheta spp. Porterweed Annual, tender perennial S. jamaicensis only 4 Cuphea x 'David Verity' David Verity Cigar Plant Perennial 4 Hamellia patens Mexican Firebush Perennial 3 Abutilon spp. Flowering Maple Tender perennial 3 Callistemon spp. Bottlebrush Shrub - evergreen 3 Canna spp. Canna, Flag Perennial Yes - some species 3 Erythrina spp. Mamou Bean, Bidwill's Coral Bean, Crybaby Tree Perennial E. herbacea only 3 Ipomoea spp. Morning Glory, Cypress Vine Vines - perennials, annuals Yes 3 Lonicera sempervirens Coral Honeysuckle Vine - Woody Yes 2 Campsis radicans Trumpet Creeper Vine - Woody Yes 2 Lantana spp. Lantana Perennial Yes - some species 2 Odontonema stricta Firespike Perennial, tender perennial 2 Pentas lanceolata Pentas Annual 2 Salvia elegans Pineapple Sage Perennial 2 Salvia greggii Autumn Sage Perennial Yes 2 Salvia x 'Wendy's Wish' Wendy's Wish Salvia Perennial, tender perennial 1 Aesculus spp. Buckeye Shrubs, trees - deciduous Yes 1 Agastache 'Summer Love' Summer Love Agastache Perennial 1 Aquilegia canadensis Columbine Perennial, biennial Yes 1 Calliandra spp. Powder Puff Tropical 1 Cuphea micropetala Giant Cigar Plant Perennial 1 Erythrina herbacea Mamou Bean Perennial Yes 1 Erythrina x bidwillii Bidwill's Coral Tree Perennial 1 Hedychium spp. Ginger Perennial 1 Impatiens capensis Jewelweed Annual Yes Votes Species Common Name Persistence US Native 1 Ipomoea quamoclit Cypress Vine Vine - woody 1 Iris spp. -

Pharmacological Activity of Desmodium Triflorum- a Review

Anu K Thankachan. et al. / Asian Journal of Phytomedicine and Clinical Research. 5(1), 2017, 33-41. Review Article CODEN: AJPCFF ISSN: 2321 – 0915 Asian Journal of Phytomedicine and Clinical Research Journal home page: www.ajpcrjournal.com PHARMACOLOGICAL ACTIVITY OF DESMODIUM TRIFLORUM- A REVIEW Anu K Thankachan *1 , Meena Chandran 1, K. Krishnakumar 2 1* Department of Pharmaceutical Analysis, St. James College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Chalakudy, Thrissur, Kerala, India. 2St James Hospital Trust Pharmaceutical Research Centre (DSIR Recognized), Chalakudy, Thrissur, Kerala, India. ABSTRACT Desmodium triflorum is a plant belongs to the family Fabaceae. It is a global species native to tropical regions and introduced to subtropical regions including the southern United States. The plant is having antipyretic, antiseptic, expectorant properties. A decoction is commonly used to treat diarrhoea and dysentery; quench thirst; and as mouthwash. The crushed plant, or a poultice of the leaves, is applied externally on wounds, ulcers, and for skin problems. In general the whole plant is used medicinally for inducing sweat and promoting digestion, anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-convulsant and anti-bacterial actions. This review explains the different pharmacological activities of Desmodium triflorum. KEYWORDS Desmodium triflorum , Anti-oxidant, Anti-inflammatory and Anti-convulsa nt. INTRODUCTION Author for Correspondence: Plants have formed the basis for treatment of diseases in traditional medicine for thousands of years and continue to play a major role in the Anu K Thankachan, primary health care of about 80% of the world’s inhabitants 1. It is also worth noting that (a) 35% of Department of Pharmaceutical Analysis, drugs contain ‘principles’ of natural origin and (b) St. -

Desmodium Cuspidatum (Muhl.) Loudon Large-Bracted Tick-Trefoil

New England Plant Conservation Program Desmodium cuspidatum (Muhl.) Loudon Large-bracted Tick-trefoil Conservation and Research Plan for New England Prepared by: Lynn C. Harper Habitat Protection Specialist Massachusetts Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program Westborough, Massachusetts For: New England Wild Flower Society 180 Hemenway Road Framingham, MA 01701 508/877-7630 e-mail: [email protected] • website: www.newfs.org Approved, Regional Advisory Council, 2002 SUMMARY Desmodium cuspidatum (Muhl.) Loudon (Fabaceae) is a tall, herbaceous, perennial legume that is regionally rare in New England. Found most often in dry, open, rocky woods over circumneutral to calcareous bedrock, it has been documented from 28 historic and eight current sites in the three states (Vermont, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts) where it is tracked by the Natural Heritage programs. The taxon has not been documented from Maine. In Connecticut and Rhode Island, the species is reported but not tracked by the Heritage programs. Two current sites in Connecticut are known from herbarium specimens. No current sites are known from Rhode Island. Although secure throughout most of its range in eastern and midwestern North America, D. cuspidatum is Endangered in Vermont, considered Historic in New Hampshire, and watch-listed in Massachusetts. It is ranked G5 globally. Very little is understood about the basic biology of this species. From work on congeners, it can be inferred that there are likely to be no problems with pollination, seed set, or germination. As for most legumes, rhizobial bacteria form nitrogen-fixing nodules on the roots of D. cuspidatum. It is unclear whether there have been any changes in the numbers or distribution of rhizobia capable of forming effective mutualisms with D. -

Galactia P. Browne, Is a Cosmopolitan Genus, Comprises About 50 Species, Distributed in Tropical, Subtropical and Warm Temperate

ISSN 0373-580 X Bol. Soc. Argent. Bot. 44 (1-2): 25 - 32. 2009 COMPARATIVE LEAF ANATOMY IN ARGENTINE GALACTIA SPECIES G. M. TOURN1, M. T. COSA 2 , G. G. ROITMAN 3 & M. P. SILVA 1 Summary: A comparative study of anatomical characters of the leaves of argentine species of Genera Galactia was carried out in order to evaluate their potential value in Taxonomy. In Argentine 14 species and some varieties from Sections Odonia and Collaearia can be found. Section Odonia: G. benthamiana Mich., G. dubia DC., G. fiebrigiana Burkart var. correntina Burkart, G. glaucophylla Harms, G. gracillima Benth., G. latisiliqua Desv., G. longifolia (Jacq.) Benth., G. marginalis Benth., G. striata (Jacq.) Urban, G. martioides Burkart, G. neesi D. C. var. australis Malme, G. pretiosa Burkart var. pretiosa, G. texana (Scheele) A. Gray and G. boavista (Vell.) Burkart from Section Collaearia. The characterization of sections is mainly based on reproductive characters, vegetative ones (exomorphological aspects) are scarcely considered. The present paper provides a description of anatomical characters of leaves in argentine species of Galactia. Some of them, may have diagnostic value in taxonomic treatment. Special emphasis is placed on the systematic significance of the midvein structure. The aim of the present study, covering 10 species (named in bold), is a) to add more data of leaf anatomy characters, thus b) to evaluate the systematic relevance and/ or ecological significance. Key words: leaves anatomy, Galactia spp., Fabaceae. Resumen: Anatomía comparada de hoja en especies argentinas de Galactia. Se realizó un estudio comparativo de la anatomía foliar de especies argentinas del género Galactia (Fabaceae), a fin de evaluar su potencial en taxonomía. -

2019 Domain Management Plan

Domain Management Plan 2019-2029 FINAL DRAFT 12/20/2019 Owner Contact: Amy Turner, Ph.D., CWB Director of Environmental Stewardship and Sustainability The University of the South Sewanee, Tennessee Office: 931-598-1447 Office: Cleveland Annex 110C Email: [email protected] Reviewed by: The Nature Conservancy Forest Stewards Guild ____________________________________________________________________________ Tract Location: Franklin and Marion Counties, Tennessee Centroid Latitude 35.982963 Longitude -85.344382 Tract Size: 13,036 acres | 5,275 hectares Land Manager: Office of Environmental Stewardship and Sustainability, The University of the South, Sewanee, Tennessee 2 Executive Summary The primary objective of this management plan is to provide a framework to outline future management and outline operations for the Office of Environmental Stewardship and Sustainability (OESS) over the next ten years. In this plan, we will briefly introduce the physical and biological setting, past land use, and current uses of the Domain. The remainder of the plan consists of an assessment of the forest, which has been divided into six conservation areas. These conservation areas contain multiple management compartments, and the six areas have similarities in topographical position and past land use. Finally, the desired future condition and project summary of each conservation area and compartment has been outlined. Background The University of the South consists of an academic campus (382 acres) with adjacent commercial and residential areas (783 acres) that are embedded within and surrounded by diverse natural lands (11,838 acres). The term “Domain” is used interchangeably to describe both the entire ~13,000 acres and the 11,800-acre natural land matrix (also referred to as the “Greater Domain”). -

Seed Volume Dataset—An Ongoing Inventory of Seed Size Expressed by Volume

Data Descriptor Seed Volume Dataset—An Ongoing Inventory of Seed Size Expressed by Volume Elsa Ganhão and Luís Silva Dias * Department of Biology, University of Évora, Ap. 94, 7000-554 Évora, Portugal; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 28 March 2019; Accepted: 23 April 2019; Published: 1 May 2019 Abstract: This paper presents a dataset of seed volumes calculated from length, width, and when available, thickness, abstracted from printed literature—essentially scientific journals and books including Floras and illustrated manuals, from online inventories, and from data obtained directly by the authors or provided by colleagues. Seed volumes were determined from the linear dimensions of seeds using published equations and decision trees. Ways of characterizing species by seed volume were compared and the minimum volume of the seed was found to be preferable. The adequacy of seed volume as a surrogate for seed size was examined and validated using published data on the relationship between light requirements for seed germination and seed size expressed as mass. Dataset: Available as supplementary file at http://home.uevora.pt/~lsdias/SVDS_03plus.csv Dataset License: CC-BY Keywords: germination in light and dark; seed size; seed volume; soil seed banks 1. Summary Seeds have been credited with being the main reason for the overall dominance of seed plants [1], which are recognized as the most successful group of plants in the widest range of environments [2]. It is recognized, apart from some exceptions, that plants and plant communities can only be understood if the importance of seeds in soil (seeds viewed not in a strict morphologic sense but rather encompassing fruits such as achenes, caryopses, cypselae, and others) is acknowledged, because at any moment, soil seed banks represent the potential population of plants through time [3].