COMMENTS WELCOME TAXES and INEQUALITY Leonard E. Burman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key Elements of the U.S. Tax System

TAX POLICY CENTER BRIEFING BOOK Key Elements of the U.S. Tax System TAXES AND THE FAMILY What are marriage penalties and bonuses? XXXX Q. What are marriage penalties and bonuses? A. A couple incurs a marriage penalty if the two pay more income tax filing as a married couple than they would pay if they were single and filed as individuals. Conversely, a couple receives a marriage bonus if they pay less tax filing as a couple than they would if they were single. CAUSES OF MARRIAGE BONUSES AND PENALTIES Marriage penalties and bonuses occur because income taxes apply to a couple, not to individual spouses. Under a progressive income tax, a couple’s income can be taxed more or less than that of two single individuals. A couple is not obliged to file a joint tax return, but their alternative—filing separate returns as a married couple—almost always results in higher tax liability. Married couples with children are more likely to incur marriage penalties than couples without children because one or both spouses could use the head of household filing status if they were able to file as singles. And tax provisions that phase in or out with income also produce marriage penalties or bonuses. Marriage penalties are more common when spouses have similar incomes. Marriage bonuses are more common when spouses have disparate incomes. Overall, couples receiving bonuses greatly outnumber those incurring penalties. MARRIAGE PENALTIES Couples in which spouses have similar incomes are more likely to incur marriage penalties than couples in which one spouse earns most of the income, because combining incomes in joint filing can push both spouses into higher tax brackets. -

1210Lowdown FINAL.Qxd:1210Lowdown 30/9/12 7:09 PM Page 1

1210Lowdown_FINAL.qxd:1210Lowdown 30/9/12 7:09 PM Page 1 VOLUME14 NUMBER 10 OCTOBER 2012 The The moral purpose of a man’s ❛❛life is the achievement of his own happiness… Any help he gives [to the welfare of others] is an exception, not a rule; an act of generosity, not a moral duty.❜❜ ——RUSSIAN-AMERICAN NOVELIST AYN RAND, goddess of today’s far-right pols seeking “philosophical” cover for their agenda of selfishness and miserliness. WRITTEN BY JIM HIGHTOWER PUBLISHER, PHILLIP FRAZER Bootstrap BS, Grover Norquistian nonsense, and plutocratic pouts of corporate elites The Big Three Myths fabricated by right wing fabulists to frame America’s elections DURING THE PAST SEVERAL YEARS, a mess of plutocratic The corporate and moneyed elites (forgive a bit of redundancy myths has been growing like kudzu across our political land- there) must be freed from tax and regulatory burdens that impede scape. This aggressive ideological vine has crept from place to their entrepreneurial creativity; place, incrementally covering over the vital spirit of egalitarian- The First Amendment must be interpreted to mean that unlimited political spending of corporate cash equals free speech; and ism that defines us as Americans and unites us as a society. Deliberately planted and nurtured by various Koch-funded front Etcetera, ad nauseam, ad infinitum. groups, these invasive myths (let’s dare call them lies) have been The whopperites are trying to pass this stuff off as some sort of deep political “philosophy” rather than confessing that it is what it spread by assorted Ayn-Randian acolytes, advancing the anti- is: Shameless kleptocratic doggerel intended to disempower the democratic notion that corporations and the wealthy are America’s many and enthrone the privileged few. -

Form W-4, Employee's Withholding Certificate

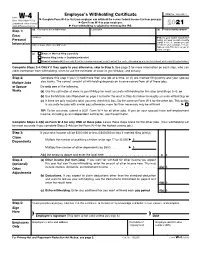

Employee’s Withholding Certificate OMB No. 1545-0074 Form W-4 ▶ (Rev. December 2020) Complete Form W-4 so that your employer can withhold the correct federal income tax from your pay. ▶ Department of the Treasury Give Form W-4 to your employer. 2021 Internal Revenue Service ▶ Your withholding is subject to review by the IRS. Step 1: (a) First name and middle initial Last name (b) Social security number Enter Address ▶ Does your name match the Personal name on your social security card? If not, to ensure you get Information City or town, state, and ZIP code credit for your earnings, contact SSA at 800-772-1213 or go to www.ssa.gov. (c) Single or Married filing separately Married filing jointly or Qualifying widow(er) Head of household (Check only if you’re unmarried and pay more than half the costs of keeping up a home for yourself and a qualifying individual.) Complete Steps 2–4 ONLY if they apply to you; otherwise, skip to Step 5. See page 2 for more information on each step, who can claim exemption from withholding, when to use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App, and privacy. Step 2: Complete this step if you (1) hold more than one job at a time, or (2) are married filing jointly and your spouse Multiple Jobs also works. The correct amount of withholding depends on income earned from all of these jobs. or Spouse Do only one of the following. Works (a) Use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App for most accurate withholding for this step (and Steps 3–4); or (b) Use the Multiple Jobs Worksheet on page 3 and enter the result in Step 4(c) below for roughly accurate withholding; or (c) If there are only two jobs total, you may check this box. -

ITEMIZING on STATE and FEDERAL TAX INCOME RETURNS: IT’S (NOW MORE) COMPLICATED David Weiner December 2, 2020

ITEMIZING ON STATE AND FEDERAL TAX INCOME RETURNS: IT’S (NOW MORE) COMPLICATED David Weiner December 2, 2020 A taxpayer’s decision to itemize deductions or to claim the standard deduction on their income tax return is often framed as a simple calculation: Claim the greater of the two so as to minimize tax liability. But in states that require taxpayers to use the same status on their state income tax return as on their federal return, this general rule can produce conflicting results if taxpayers examine liability separately on their federal and state returns. Itemized deductions might be greater than the standard deduction on a state income tax return, but the reverse could be true on a federal return. Recent federal law changes have further complicated the choice. When the federal standard deduction was nearly doubled beginning in 2018, many more taxpayers found a conflict between the best itemization scenario on federal and state income tax returns. Those taxpayers must now calculate their federal and state income taxes under both scenarios if they want to minimize their combined state and federal income tax liability. Many taxpayers in states that link federal and state itemization choices are affected. In Maryland, for example, more than 200,000 taxpayers could benefit by itemizing on their federal returns when that may not be the obvious choice. In this brief, I examine the links between federal and state itemization decisions and explore the implications of relaxing state rules requiring that state itemization choices match federal ones. elatively few federal taxpayers itemize deductions on their income tax returns under current law, and those who do tend to have very high incomes. -

Chapter 2: What's Fair About Taxes?

Hoover Classics : Flat Tax hcflat ch2 Mp_35 rev0 page 35 2. What’s Fair about Taxes? economists and politicians of all persuasions agree on three points. One, the federal income tax is not sim- ple. Two, the federal income tax is too costly. Three, the federal income tax is not fair. However, economists and politicians do not agree on a fourth point: What does fair mean when it comes to taxes? This disagree- ment explains, in large measure, why it so difficult to find a replacement for the federal income tax that meets the other goals of simplicity and low cost. In recent years, the issue of fairness has come to overwhelm the other two standards used to evaluate tax systems: cost (efficiency) and simplicity. Recall the 1992 presidential campaign. Candidate Bill Clinton preached that those who “benefited unfairly” in the 1980s [the Tax Reform Act of 1986 reduced the top tax rate on upper-income taxpayers from 50 percent to 28 percent] should pay their “fair share” in the 1990s. What did he mean by such terms as “benefited unfairly” and should pay their “fair share?” Were the 1985 tax rates fair before they were reduced in 1986? Were the Carter 1980 tax rates even fairer before they were reduced by President Reagan in 1981? Were the Eisenhower tax rates fairer still before President Kennedy initiated their reduction? Were the original rates in the first 1913 federal income tax unfair? Were the high rates that prevailed during World Wars I and II fair? Were Andrew Mellon’s tax Hoover Classics : Flat Tax hcflat ch2 Mp_36 rev0 page 36 36 The Flat Tax rate cuts unfair? Are the higher tax rates President Clin- ton signed into law in 1993 the hallmark of a fair tax system, or do rates have to rise to the Carter or Eisen- hower levels to be fair? No aspect of federal income tax policy has been more controversial, or caused more misery, than alle- gations that some individuals and income groups don’t pay their fair share. -

Your Federal Tax Burden Under Current Law and the Fairtax by Ross Korves

A FairTaxSM White Paper Your federal tax burden under current law and the FairTax by Ross Korves As farmers and ranchers prepare 2006 federal income tax returns or provide income and expense information to accountants and other tax professionals, a logical question is how would the tax burden change under the FairTax? The FairTax would eliminate all individual and corporate income taxes, all payroll taxes and self-employment taxes for Social Security and Medicare, and the estate tax and replace them with a national retail sales tax on final consumption of goods and services. Payroll and self-employment taxes The starting point in calculating the current tax burden is payroll taxes and self-employment taxes. Most people pay more money in payroll and self-employment taxes than they do in income taxes because there are no standard deductions or personal exemptions that apply to payroll and self-employment taxes. You pay tax on the first dollar earned. While employees see only 7.65 percent taken out of their paychecks, the reality is that the entire 15.3 percent payroll tax is part of the cost of having an employee and is a factor in determining how much an employer can afford to pay in wages. Self-employed taxpayers pay both the employer and employee portions of the payroll tax on their earnings, and the entire 15.3 percent on 92.35 percent of their self-employed income (they do not pay on the 7.65 percent of wages that employees do not receive as income); however, they are allowed to deduct the employer share of payroll taxes against the income tax. -

2021 Instructions for Form 6251

Note: The draft you are looking for begins on the next page. Caution: DRAFT—NOT FOR FILING This is an early release draft of an IRS tax form, instructions, or publication, which the IRS is providing for your information. Do not file draft forms and do not rely on draft forms, instructions, and publications for filing. We do not release draft forms until we believe we have incorporated all changes (except when explicitly stated on this coversheet). However, unexpected issues occasionally arise, or legislation is passed—in this case, we will post a new draft of the form to alert users that changes were made to the previously posted draft. Thus, there are never any changes to the last posted draft of a form and the final revision of the form. Forms and instructions generally are subject to OMB approval before they can be officially released, so we post only drafts of them until they are approved. Drafts of instructions and publications usually have some changes before their final release. Early release drafts are at IRS.gov/DraftForms and remain there after the final release is posted at IRS.gov/LatestForms. All information about all forms, instructions, and pubs is at IRS.gov/Forms. Almost every form and publication has a page on IRS.gov with a friendly shortcut. For example, the Form 1040 page is at IRS.gov/Form1040; the Pub. 501 page is at IRS.gov/Pub501; the Form W-4 page is at IRS.gov/W4; and the Schedule A (Form 1040/SR) page is at IRS.gov/ScheduleA. -

The Viability of the Fair Tax

The Fair Tax 1 Running head: THE FAIR TAX The Viability of The Fair Tax Jonathan Clark A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Fall 2008 The Fair Tax 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Gene Sullivan, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Donald Fowler, Th.D. Committee Member ______________________________ JoAnn Gilmore, M.B.A. Committee Member ______________________________ James Nutter, D.A. Honors Director ______________________________ Date The Fair Tax 3 Abstract This thesis begins by investigating the current system of federal taxation in the United States and examining the flaws within the system. It will then deal with a proposal put forth to reform the current tax system, namely the Fair Tax. The Fair Tax will be examined in great depth and all aspects of it will be explained. The objective of this paper is to determine if the Fair Tax is a viable solution for fundamental tax reform in America. Both advantages and disadvantages of the Fair Tax will objectively be pointed out and an educated opinion will be given regarding its feasibility. The Fair Tax 4 The Viability of the Fair Tax In 1986 the United States federal tax code was changed dramatically in hopes of simplifying the previous tax code. Since that time the code has undergone various changes that now leave Americans with over 60,000 pages of tax code, rules, and rulings that even the most adept tax professionals do not understand. -

Tax Reform Options: Marginal Rates on High-Income Taxpayers, Capital Gains, and Dividends

Embargoed Until 10am September 14, 2011 Statement of Leonard E. Burman Daniel Patrick Moynihan Professor of Public Affairs Maxwell School Syracuse University Before the Senate Committee on Finance Tax Reform Options: Marginal Rates on High-Income Taxpayers, Capital Gains, and Dividends September 14, 2011 Chairman Baucus, Ranking Member Hatch, Members of the Committee. Thank you for inviting me to testify on tax reform options affecting high-income taxpayers. I applaud the committee for devoting much of the past year to examining ways to make the tax code simpler, fairer, and more conducive to economic growth, and I’m honored to be asked to contribute to those deliberations. In summary, here are my main points: Economic theory suggests that the degree of progressivity should balance the gains from mitigating economic inequality and risk-sharing against the costs in terms of disincentives created by higher tax rates. The optimal top tax rate depends on social norms and the government’s revenue needs. Experience and a range of empirical evidence suggests that the rates in effect in the 1990s would not unduly diminish economic growth. However, a more efficient option would be to broaden the base (reform or eliminate tax expenditures and eliminate loopholes) to achieve distributional goals while keeping top rates relatively low. The biggest loophole is the lower tax rate on capital gains. Several bipartisan tax reform plans, including the Bipartisan Policy Center plan that I contributed to, would tax capital gains at the same rate as other income. Combined with a substantial reduction in tax expenditures, this allows for a cut in top income rates while maintaining the progressivity of the tax system. -

Notice 21-02 Changes to Deductions for Individuals

Policy and Research 109 SW 9th Street Phone: 785-368-8222 PO Box 3506 Fax: 785-296-1279 Topeka KS 66601-3506 www.ksrevenue.org Mark A. Burghart, Secretary Laura Kelly, Governor NOTICE 21-02 CHANGES TO DEDUCTIONS FOR INDIVIDUALS (JULY 29, 2021) Standard Deduction During the 2021 Legislative Session Senate Bill 50 was passed and signed into law. This Bill amended K.S.A. 79-32,119 to change the standard deduction for individuals filing Kansas income tax returns. Specifically, Section 9 of the Bill includes new statutory language, found in subsection (c)(2), which provides: (2) For tax year 2021, and all tax years thereafter, the standard deduction amount of an individual, including husband and wife who are either both residents or who file a joint return as if both were residents, shall be as follows: Single individual filing status, $3,500; married filing status, $8,000; and head of household filing status, $6,000. In accordance with the new law, for tax years 2021, and all subsequent tax years, the base standard deduction will be: $3,500 for single filing status; $8,000 for married filing joint status; $4,000 for married filing separate status; and $6,000 for head of household filing status. Itemized Deductions Senate Bill 50 also amended K.S.A. 79-32,120 to expand the ability to claim itemized deductions for individuals filing Kansas income tax returns. Specifically, Section 10 of the Bill includes new statutory language, found in subsection (a)(1)(B), which provides: (B) For tax year 2021, and all tax years thereafter, an individual may elect to deduct the Kansas itemized deduction in lieu of the Kansas standard deduction, regardless of whether or not such individual’s federal taxable income is determined by itemizing deductions from such individual’s federal adjusted gross income. -

How Marriage Penalties Change Under the 2001 Tax Bill

How Marriage Penalties Change under the 2001 Tax Bill Adam Carasso and C. Eugene Steuerle* *Adam Carasso is a research associate and C. Eugene Steuerle is a senior fellow at the Urban Institute. This paper could not have been written without support from the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the Ford Foundation, and the George Gund Foundation. Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of The Urban Institute, its board, or its funders. 1 Abstract This paper examines how the various provisions of the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 (EGTRRA) change marriage penalties and subsidies for different, hypothetical pairings of heads of household with single workers filing a joint return. Heads of household are assumed to have two children—both eligible for the earned income tax credit (EITC) and Child Tax Credit—and the analysis is conducted for families with total adjusted gross incomes (AGI) of up to $80,000, with special attention to those families with combined AGI of $35,000 or less who often face marriage penalties from expenditure programs. Additionally, our simulations take place in 2010 when all provisions of EGTRRA will be fully implemented, although we present our results in real 2001 dollars. Our research focus was to examine the additional marriage penalties that heads of household face in the way of loss of valuable tax benefits for which two single, childless taxpayers who marry would not be eligible. We modeled the impact of six pertinent provisions from the tax bill: the refundable, doubled child credit, the new 10 percent tax bracket, the newly expanded EITC for married couples, the new standard deduction for married couples, the new 15 percent tax bracket for married couples, and the new 25 percent tax bracket. -

Leonard E. Burman Page 1

Leonard E. Burman Page 1 LEONARD E. BURMAN Center for Policy Research 426 Eggers Hall Syracuse University Syracuse, NY 13244-1020 Phone: (703) 216-5085 Email: [email protected] Education Ph.D. in Economics, University of Minnesota, 1985 A.B. in Economics, Wesleyan University, 1975 Employment 2017- Institute Fellow, The Urban Institute 2015-2017 Robert C. Pozen Director, Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center 2013-2015 Director, Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center (Urban Institute) 2013- Professor of Public Administration and International Affairs and (since March 2014) Paul Volcker Professor of Behavioral Economics, Syracuse University. 2009-2013 Daniel Patrick Moynihan Professor, Syracuse University 2010 Visiting Professor, UCLA School of Law 2002-2009 Director, Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center (Urban Institute) 2008-2009 Institute Fellow, Urban Institute 2000-2008 Senior Fellow, Urban Institute 2000-2008 Visiting Professor, Georgetown University Public Policy Institute 2000-present Fiscal Analysis Division Panel of Experts, International Monetary Fund 1998-2000 Deputy Assistant Secretary (Tax Analysis), U.S. Department of the Treasury 1997-1998 Senior Research Associate, Urban Institute 1988-1997 Senior Analyst, Tax Analysis Division, U.S. Congressional Budget Office 1985-1988 Financial Economist, Office of Tax Analysis, Department of Treasury 1983-1985 Instructor, Bates College, Lewiston, ME 1975-1978 Economist, Data Resources, Inc. (DRI), Lexington, MA Publications and Papers “How Shifting from Traditional IRAs to Roth IRAs Affects Personal and Government Finances,” Tax Policy Center, 2019, with William G. Gale and Aaron Krupkin. “Roth IRAs Versus Traditional IRAs: Implications for Individuals and Government,” Tax Policy Center Policy Brief, 2019, with William G. Gale and Aaron Krupkin. 1 Leonard E.