ITEMIZING on STATE and FEDERAL TAX INCOME RETURNS: IT’S (NOW MORE) COMPLICATED David Weiner December 2, 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key Elements of the U.S. Tax System

TAX POLICY CENTER BRIEFING BOOK Key Elements of the U.S. Tax System TAXES AND THE FAMILY What are marriage penalties and bonuses? XXXX Q. What are marriage penalties and bonuses? A. A couple incurs a marriage penalty if the two pay more income tax filing as a married couple than they would pay if they were single and filed as individuals. Conversely, a couple receives a marriage bonus if they pay less tax filing as a couple than they would if they were single. CAUSES OF MARRIAGE BONUSES AND PENALTIES Marriage penalties and bonuses occur because income taxes apply to a couple, not to individual spouses. Under a progressive income tax, a couple’s income can be taxed more or less than that of two single individuals. A couple is not obliged to file a joint tax return, but their alternative—filing separate returns as a married couple—almost always results in higher tax liability. Married couples with children are more likely to incur marriage penalties than couples without children because one or both spouses could use the head of household filing status if they were able to file as singles. And tax provisions that phase in or out with income also produce marriage penalties or bonuses. Marriage penalties are more common when spouses have similar incomes. Marriage bonuses are more common when spouses have disparate incomes. Overall, couples receiving bonuses greatly outnumber those incurring penalties. MARRIAGE PENALTIES Couples in which spouses have similar incomes are more likely to incur marriage penalties than couples in which one spouse earns most of the income, because combining incomes in joint filing can push both spouses into higher tax brackets. -

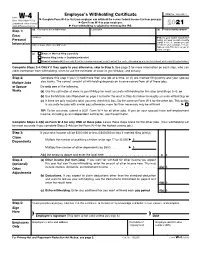

Form W-4, Employee's Withholding Certificate

Employee’s Withholding Certificate OMB No. 1545-0074 Form W-4 ▶ (Rev. December 2020) Complete Form W-4 so that your employer can withhold the correct federal income tax from your pay. ▶ Department of the Treasury Give Form W-4 to your employer. 2021 Internal Revenue Service ▶ Your withholding is subject to review by the IRS. Step 1: (a) First name and middle initial Last name (b) Social security number Enter Address ▶ Does your name match the Personal name on your social security card? If not, to ensure you get Information City or town, state, and ZIP code credit for your earnings, contact SSA at 800-772-1213 or go to www.ssa.gov. (c) Single or Married filing separately Married filing jointly or Qualifying widow(er) Head of household (Check only if you’re unmarried and pay more than half the costs of keeping up a home for yourself and a qualifying individual.) Complete Steps 2–4 ONLY if they apply to you; otherwise, skip to Step 5. See page 2 for more information on each step, who can claim exemption from withholding, when to use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App, and privacy. Step 2: Complete this step if you (1) hold more than one job at a time, or (2) are married filing jointly and your spouse Multiple Jobs also works. The correct amount of withholding depends on income earned from all of these jobs. or Spouse Do only one of the following. Works (a) Use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App for most accurate withholding for this step (and Steps 3–4); or (b) Use the Multiple Jobs Worksheet on page 3 and enter the result in Step 4(c) below for roughly accurate withholding; or (c) If there are only two jobs total, you may check this box. -

Itep Guide to Fair State and Local Taxes: About Iii

THE GUIDE TO Fair State and Local Taxes 2011 Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy 1616 P Street, NW, Suite 201, Washington, DC 20036 | 202-299-1066 | www.itepnet.org | [email protected] THE ITEP GUIDE TO FAIR STATE AND LOCAL TAXES: ABOUT III About the Guide The ITEP Guide to Fair State and Local Taxes is designed to provide a basic overview of the most important issues in state and local tax policy, in simple and straightforward language. The Guide is also available to read or download on ITEP’s website at www.itepnet.org. The web version of the Guide includes a series of appendices for each chapter with regularly updated state-by-state data on selected state and local tax policies. Additionally, ITEP has published a series of policy briefs that provide supplementary information to the topics discussed in the Guide. These briefs are also available on ITEP’s website. The Guide is the result of the diligent work of many ITEP staffers. Those primarily responsible for the guide are Carl Davis, Kelly Davis, Matthew Gardner, Jeff McLynch, and Meg Wiehe. The Guide also benefitted from the valuable feedback of researchers and advocates around the nation. Special thanks to Michael Mazerov at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. About ITEP Founded in 1980, the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) is a non-profit, non-partisan research organization, based in Washington, DC, that focuses on federal and state tax policy. ITEP’s mission is to inform policymakers and the public of the effects of current and proposed tax policies on tax fairness, government budgets, and sound economic policy. -

Chapter 2: What's Fair About Taxes?

Hoover Classics : Flat Tax hcflat ch2 Mp_35 rev0 page 35 2. What’s Fair about Taxes? economists and politicians of all persuasions agree on three points. One, the federal income tax is not sim- ple. Two, the federal income tax is too costly. Three, the federal income tax is not fair. However, economists and politicians do not agree on a fourth point: What does fair mean when it comes to taxes? This disagree- ment explains, in large measure, why it so difficult to find a replacement for the federal income tax that meets the other goals of simplicity and low cost. In recent years, the issue of fairness has come to overwhelm the other two standards used to evaluate tax systems: cost (efficiency) and simplicity. Recall the 1992 presidential campaign. Candidate Bill Clinton preached that those who “benefited unfairly” in the 1980s [the Tax Reform Act of 1986 reduced the top tax rate on upper-income taxpayers from 50 percent to 28 percent] should pay their “fair share” in the 1990s. What did he mean by such terms as “benefited unfairly” and should pay their “fair share?” Were the 1985 tax rates fair before they were reduced in 1986? Were the Carter 1980 tax rates even fairer before they were reduced by President Reagan in 1981? Were the Eisenhower tax rates fairer still before President Kennedy initiated their reduction? Were the original rates in the first 1913 federal income tax unfair? Were the high rates that prevailed during World Wars I and II fair? Were Andrew Mellon’s tax Hoover Classics : Flat Tax hcflat ch2 Mp_36 rev0 page 36 36 The Flat Tax rate cuts unfair? Are the higher tax rates President Clin- ton signed into law in 1993 the hallmark of a fair tax system, or do rates have to rise to the Carter or Eisen- hower levels to be fair? No aspect of federal income tax policy has been more controversial, or caused more misery, than alle- gations that some individuals and income groups don’t pay their fair share. -

Your Federal Tax Burden Under Current Law and the Fairtax by Ross Korves

A FairTaxSM White Paper Your federal tax burden under current law and the FairTax by Ross Korves As farmers and ranchers prepare 2006 federal income tax returns or provide income and expense information to accountants and other tax professionals, a logical question is how would the tax burden change under the FairTax? The FairTax would eliminate all individual and corporate income taxes, all payroll taxes and self-employment taxes for Social Security and Medicare, and the estate tax and replace them with a national retail sales tax on final consumption of goods and services. Payroll and self-employment taxes The starting point in calculating the current tax burden is payroll taxes and self-employment taxes. Most people pay more money in payroll and self-employment taxes than they do in income taxes because there are no standard deductions or personal exemptions that apply to payroll and self-employment taxes. You pay tax on the first dollar earned. While employees see only 7.65 percent taken out of their paychecks, the reality is that the entire 15.3 percent payroll tax is part of the cost of having an employee and is a factor in determining how much an employer can afford to pay in wages. Self-employed taxpayers pay both the employer and employee portions of the payroll tax on their earnings, and the entire 15.3 percent on 92.35 percent of their self-employed income (they do not pay on the 7.65 percent of wages that employees do not receive as income); however, they are allowed to deduct the employer share of payroll taxes against the income tax. -

Section 111.—Recovery of Tax Benefit Items 26 CFR 1.111-1

Section 111.—Recovery of Tax Benefit Items 26 CFR 1.111-1: Recovery of certain items previously deducted or credited. (Also: § 164; 1.164-1.) Rev. Rul. 2019-11 ISSUE If a taxpayer received a tax benefit from deducting state and local taxes under section 164 of the Internal Revenue Code in a prior taxable year, and the taxpayer recovers all or a portion of those taxes in the current taxable year, what portion of the recovery must the taxpayer include in gross income? FACTS In Situations 1 through 4 below, the taxpayers are unmarried individuals whose filing status is “single” and who itemized deductions on their federal income tax returns for 2018 in lieu of using their standard deduction of $12,000. The taxpayers did not pay or accrue the taxes in carrying on a trade or business or an activity described in section 212. For 2018, the taxpayers were not subject to alternative minimum tax under section 55 and were not entitled to any credit against income tax. The taxpayers use the cash receipts and disbursements method of accounting. Situation 1: Taxpayer A paid local real property taxes of $4,000 and state income taxes of $5,000 in 2018. A’s state and local tax deduction was not limited by section 164(b)(6) because it was below $10,000. Including other allowable itemized deductions, A claimed a total of $14,000 in itemized deductions on A’s 2018 federal income tax return. In 2019, A received a $1,500 state income tax refund due to A’s overpayment of state income taxes in 2018. -

2021 Instructions for Form 6251

Note: The draft you are looking for begins on the next page. Caution: DRAFT—NOT FOR FILING This is an early release draft of an IRS tax form, instructions, or publication, which the IRS is providing for your information. Do not file draft forms and do not rely on draft forms, instructions, and publications for filing. We do not release draft forms until we believe we have incorporated all changes (except when explicitly stated on this coversheet). However, unexpected issues occasionally arise, or legislation is passed—in this case, we will post a new draft of the form to alert users that changes were made to the previously posted draft. Thus, there are never any changes to the last posted draft of a form and the final revision of the form. Forms and instructions generally are subject to OMB approval before they can be officially released, so we post only drafts of them until they are approved. Drafts of instructions and publications usually have some changes before their final release. Early release drafts are at IRS.gov/DraftForms and remain there after the final release is posted at IRS.gov/LatestForms. All information about all forms, instructions, and pubs is at IRS.gov/Forms. Almost every form and publication has a page on IRS.gov with a friendly shortcut. For example, the Form 1040 page is at IRS.gov/Form1040; the Pub. 501 page is at IRS.gov/Pub501; the Form W-4 page is at IRS.gov/W4; and the Schedule A (Form 1040/SR) page is at IRS.gov/ScheduleA. -

2019 M1SA, Minnesota Itemized Deductions

*191161* 2019 Schedule M1SA, Minnesota Itemized Deductions Your First Name and Initial Last Name Your Social Security Number Medical and Dental Expenses 1 Medical and dental expenses (see instructions) . 1 2 Enter the amount from line 1 of Form M1 . If zero or less, enter 0 . 2 3 Multiply line 2 by 10% (.10). 3 4 Subtract line 3 from line 1. If line 3 is more than line 1, enter 0 . 4 Taxes You Paid 5 Real estate taxes (see instructions) . 5 6 Personal property taxes (see instructions) . 6 7 Add lines 5 and 6 . 7 8 Enter the lesser of line 7 or $10,000 ($5,000 if married filing separate) 8 9 Other taxes. List the type and amount . 9 10 Add lines 8 and 9 . 10 Interest You Paid 11 Home mortgage interest and points on federal Form 1098 . 11 12 Home mortgage interest and points not reported to you on Form 1098 (see instructions) 12 13 Investment interest expense . 13 14 Add lines 11 through 13 . 14 Charitable Contributions 15 Charitable contributions by cash or check (see instructions) . 15 16 Charitable contributions by other than cash or check (see instructions) 16 17 Carryover of charitable contributions from a prior year . 17 18 Add lines 15 through 17 . 18 Casualty and Theft Losses 19 Casualty or theft loss (enclose Schedule M1CAT) . 19 Unreimbursed Employee Business Expenses 20 Unreimbursed employee expenses (enclose Schedule M1UE) . 20 21 Enter the amount from line 1 of Form M1 . If zero or less, enter 0 . 21 22 Multiply line 21 by 2% (.02) . -

Evaluating the Charitable Deduction and Proposed Reforms 5

Making the World Safe for Philanthropy The Wartime Origins and Peacetime Development of the Tax Deduction for Charitable Giving Joseph J. Thorndike April 2013 DRAFT Copyright © April 2013. The Urban Institute. Permission is granted for reproduction of this file, with attribution to the Urban Institute. This publication is part of the Urban Institute’s Tax Policy and Charities project. The purpose of this project is to analyze the many interactions between the tax system and the charitable sector, with special emphasis on the ongoing fiscal debates at both the federal and state levels. For further information and related publications, see our web site at http://www.urban.org/taxandcharities. The Tax Policy and Charities project is funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, the Wasie Foundation, the Rasmuson Foundation, and other donors through June 2014. The findings and conclusions contained in the publications posted here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of either foundation. The Urban Institute is a nonprofit, nonpartisan policy research and educational organization that examines the social, economic, and governance problems facing the nation. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Urban Institute, its trustees, or its funders. DRAFT Contents 1917 6 1944 9 1981–86 12 Conclusion 17 Notes 19 DRAFT Making the World Safe for Philanthropy As Washington wrestles with its long-term fiscal problems—and its near-term political gridlock—the tax deduction for charitable giving has been getting some special attention.1 As one of the nation’s most costly tax expenditures—and its third most expensive itemized deduction—the deduction is an obvious target for reform.2 Add to this its less-than-progressive incidence, and you open the door to meaningful change.3 Or maybe you don’t. -

The Viability of the Fair Tax

The Fair Tax 1 Running head: THE FAIR TAX The Viability of The Fair Tax Jonathan Clark A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Fall 2008 The Fair Tax 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Gene Sullivan, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Donald Fowler, Th.D. Committee Member ______________________________ JoAnn Gilmore, M.B.A. Committee Member ______________________________ James Nutter, D.A. Honors Director ______________________________ Date The Fair Tax 3 Abstract This thesis begins by investigating the current system of federal taxation in the United States and examining the flaws within the system. It will then deal with a proposal put forth to reform the current tax system, namely the Fair Tax. The Fair Tax will be examined in great depth and all aspects of it will be explained. The objective of this paper is to determine if the Fair Tax is a viable solution for fundamental tax reform in America. Both advantages and disadvantages of the Fair Tax will objectively be pointed out and an educated opinion will be given regarding its feasibility. The Fair Tax 4 The Viability of the Fair Tax In 1986 the United States federal tax code was changed dramatically in hopes of simplifying the previous tax code. Since that time the code has undergone various changes that now leave Americans with over 60,000 pages of tax code, rules, and rulings that even the most adept tax professionals do not understand. -

Tax Reform Options: Marginal Rates on High-Income Taxpayers, Capital Gains, and Dividends

Embargoed Until 10am September 14, 2011 Statement of Leonard E. Burman Daniel Patrick Moynihan Professor of Public Affairs Maxwell School Syracuse University Before the Senate Committee on Finance Tax Reform Options: Marginal Rates on High-Income Taxpayers, Capital Gains, and Dividends September 14, 2011 Chairman Baucus, Ranking Member Hatch, Members of the Committee. Thank you for inviting me to testify on tax reform options affecting high-income taxpayers. I applaud the committee for devoting much of the past year to examining ways to make the tax code simpler, fairer, and more conducive to economic growth, and I’m honored to be asked to contribute to those deliberations. In summary, here are my main points: Economic theory suggests that the degree of progressivity should balance the gains from mitigating economic inequality and risk-sharing against the costs in terms of disincentives created by higher tax rates. The optimal top tax rate depends on social norms and the government’s revenue needs. Experience and a range of empirical evidence suggests that the rates in effect in the 1990s would not unduly diminish economic growth. However, a more efficient option would be to broaden the base (reform or eliminate tax expenditures and eliminate loopholes) to achieve distributional goals while keeping top rates relatively low. The biggest loophole is the lower tax rate on capital gains. Several bipartisan tax reform plans, including the Bipartisan Policy Center plan that I contributed to, would tax capital gains at the same rate as other income. Combined with a substantial reduction in tax expenditures, this allows for a cut in top income rates while maintaining the progressivity of the tax system. -

Income 4: State Income Tax Addback for Individuals

Income 4: State Income Tax Addback for Individuals Individuals who itemize deductions on their federal income tax returns and claim a deduction for state income tax must add back the deducted state income tax on line 2 of their Colorado income tax return (Form 104). The amount that must be added back is generally equal to the amount deducted on line 5a of the taxpayer’s federal Schedule A. However, the amount a taxpayer must add back may be limited, as discussed in this publication. The addback requirement does not apply to individuals who claim the standard deduction on their federal income tax returns or to individuals who claim a deduction for general sales taxes, rather than state and local income taxes. Corporations, estates, and trusts are also required to add back certain state taxes deducted on their federal returns. However, the information in this publication pertains only to individual income taxpayers. FEDERAL DEDUCTION FOR STATE AND LOCAL TAXES Individuals who itemize deductions on their federal returns can deduct various state and local taxes. However, the addback requirement applies only to state income taxes deducted on their federal returns. Individuals must add back the state income taxes they deduct, regardless of whether the state income taxes were paid to Colorado or to another state. Taxpayers are not required to add back any of the following types of taxes that they may have deducted on their federal Schedule A: general sales taxes; local income or occupational taxes; state or local real estate taxes; or state or local personal property taxes. LIMITATIONS Various limitations may reduce the amount an individual taxpayer must add back.