21St Century Technologies, Geopolitics, and the US-Japan Alliance: Recognizing Game

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTERNATIONAL Call for Papers & Registration of Interest

ORGANIZED BY: HOSTED BY: st 71 INTERNATIONAL ASTRONAUTICAL CONGRESS 12–16 October 2020 | Dubai, United Arab Emirates Call for Papers & Registration of Interest Second Announcement SUPPORTED BY: Inspire, Innovate & Discover for the Benefit of Humankind IAC2020.ORG Contents 1. Message from the International Astronautical Federation (IAF) 2 2. Message from the Local Organizing Committee 2 3. Message from the IPC Co-Chairs 3 4. Messages from the Partner Organizations 4 5. International Astronautical Federation (IAF) 5 6. International Academy of Astronautics (IAA) 10 7. International Institute of Space Law (IISL) 11 8. Message from the IAF Vice President for Technical Activities 12 9. IAC 2020 Technical Sessions Deadlines Calendar 49 10. Preliminary IAC 2020 at a Glance 50 11. Instructions to Authors 51 Connecting @ll Space People 12. Space in the United Arab Emirates 52 www.iafastro.org IAF Alliance Programme Partners 2019 1 71st IAC International Astronautical Congress 12–16 October 2020, Dubai 1. Message from the International Astronautical Federation (IAF) 3. Message from the International Programme Committee (IPC) Greetings! Co-Chairs It is our great pleasure to invite you to the 71st International Astronautical Congress (IAC) to take place in Dubai, United Arab Emirates On behalf of the International Programme Committee, it is a great pleasure to invite you to submit an abstract for the 71st International from 12 – 16 October 2020. Astronautical Congress IAC 2020 that will be held in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. The IAC is an initiative to bring scientists, practitioners, engineers and leaders of space industry and agencies together in a single platform to discuss recent research breakthroughs, technical For the very first time, the IAC will open its doors to the global space community in the United Arab Emirates, the first Arab country to advances, existing opportunities and emerging space technologies. -

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 02/16/2021 11:18:01 AM

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 02/16/2021 11:18:01 AM 02/12/21 Friday This material is distributed by Ghebi LLC on behalf of Federal State Unitary Enterprise Rossiya Segodnya International Information Agency, and additional information is on file with the Department of Justice, Washington, District of Columbia. Lincoln Project Faces Exodus of Advisers Amid Sexual Harassment Coverup Scandal by Morgan Artvukhina Donald Trump was a political outsider in the 2016 US presidential election, and many Republicans refused to accept him as one of their own, dubbing themselves "never-Trump" Republicans. When he sought re-election in 2020, the group rallied in support of his Democratic challenger, now the US president, Joe Biden. An increasing number of senior figures in the never-Trump political action committee The Lincoln Project (TLP) have announced they are leaving, with three people saying Friday they were calling it quits in the wake of a sexual assault scandal involving co-founder John Weaver. "I've always been transparent about all my affiliations, as I am now: I told TLP leadership yesterday that I'm stepping down as an unpaid adviser as they sort this out and decide their future direction and organization," Tom Nichols, a “never-Trump” Republican who supported the group’s effort to rally conservative support for US President Joe Biden in the 2020 election, tweeted on Friday afternoon. Nichols was joined by another adviser, Kurt Bardella and by Navvera Hag, who hosted the PAC’s online show “The Lincoln Report.” Late on Friday, Lincoln Project co-founder Steve Schmidt reportedly announced his resignation following accusations from PAC employees that he handled the harassment scandal poorly, according to the Daily Beast. -

A Legal Framework for Outer Space Activities in Malaysia Tunku Intan Mainura Faculty of Law, University Teknologi Mara,40450 Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia

International Journal of Scientific Research and Management (IJSRM) ||Volume||06||Issue||04||Pages||SH-2018-81-90||2018|| Website: www.ijsrm.in ISSN (e): 2321-3418 Index Copernicus value (2015): 57.47, (2016):93.67, DOI: 10.18535/ijsrm/v6i4.sh03 A Legal Framework for Outer Space Activities in Malaysia Tunku Intan Mainura Faculty of Law, university teknologi Mara,40450 Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia Introduction 7 One common similarity that Malaysia has between and space education programme . In order for itself and the international space programme1 is the Malaysia to ensure that its activities under the year 1957. For Malaysia it was the year of programme of space science and technology can be Independence2 and for the international space effectively undertaken, Malaysia has built space infrastructures, which includes the national programme, the first satellite, Sputnik 1, was 8 launched to outer space by the Soviet Union observatory and remote sensing centres . Activities (USSR)3. That was 56 years ago. Today outer space under the space science and technology programme is familiar territory to states at large and Malaysia is includes the satellite technology activities. Under one of the players in this arena4. Although it has this activity, Malaysia has participated in it by been commented by some writers that ‘Malaysia having six satellites in orbit. Nevertheless, these can be considered as new in space activities, since satellites were not launched from Malaysia’s territory, as Malaysia does not have a launching its first satellite was only launched into orbit in 9 1997’5, nevertheless, it should be highlighted here facility . -

Satoshi Kogure, Co-Chair of Multi-GNSS Asia Director, National Space Policy Secretariat, Cabinet Office, the Government of Japan

MULTI-GNSS ASIA Satoshi Kogure, Co-Chair of Multi-GNSS Asia Director, National Space Policy Secretariat, Cabinet Office, The Government of Japan Supported by: WHAT’S MGA? Multi-GNSS Asia (MGA) which promotes multi GNSS in the Asia and Oceania regions and encourages GNSS service providers and user communities to develop new applications and businesses. The MGA activities are reported annually in the ICG providers’ forum. The MGA also supports developing countries in achieving its SDGs through technical support on GNSS via seminars for policy makers and more. Aug. 2020 GISTDA Aug. 2019 GISTDA Oct. 2018 RMIT, FrontierSI, GA, GNSS,asia, QSS Oct. 2017 LAPAN, BELS, GNSS.asia, QSS, JAXA Nov. 2016 Univ. Philippines, NAMRIA, Phivolcs, BELS, GNSS.asia, QSS, JAXA Dec. 2015 Soartech, BELS, GNSS.asia, QSS, JAXA, SPAC Oct. 2014 NSTDA, G-NAVIS, QSS, JAXA, SPAC Dec. 2013 G-NAVIS, HUST, QSS, JAXA, SPAC Dec. 2012 ANGKASA, JAXA, G-NAVIS, SPAC Nov. 2011 GTC, KARI, JAXA, SPAC Nov. 2010 IGNSS, JAXA, SPAC https://www.multignss.asia https://www.multignss.asia/contact Jan. 2010 GISTDA, JAXA, SPAC https://www.facebook.com/multignss Conference and Exhibition What is MGA? To share the latest advancements to the GNSS and PNT landscape, the MGA conference is organized annually in a different location across the Asia- Oceania region. Delegates can also find out about new technologies, products and services, updates on R&D projects and achievements. The Pillars of conference attracts participants from industry, government and academia from around the world, making its networking opportunities second-to- none. Activity Networking and Capacity Building via Webinars, Workshops and Forums To make sure you’re on top of rapidly changing technological developments • Conference and Exhibition in GNSS, PNT technologies and its utilization in the business landscape, MGA hosts webinars, regional workshops and networking forums. -

Statement by Director General Malaysian Space Agency (Mysa) to the 58Th Session of the Scientific and Technical Subcommittee Of

STATEMENT BY DIRECTOR GENERAL MALAYSIAN SPACE AGENCY (MYSA) TO THE 58TH SESSION OF THE SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE PEACEFUL USES OF OUTER SPACE (STSC COPOUS), VIENNA, 19-30 APRIL 2021 AGENDA ITEM 3: GENERAL EXCHANGE OF VIEWS AND INTRODUCTION OF REPORTS SUBMITTED ON NATIONAL ACTIVITIES Madam Chair, At the outset, my delegation would like to express appreciation to you for your leadership and commitment, and the Secretariat for the excellent preparations made for this session, especially during these unprecedented times. I wish to assure you of our support and cooperation in ensuring the successful outcome of this session. 2. Malaysia associates itself with the statement of the Group of 77 and China delivered by Costa Rica and would like to make the following remarks in its national capacity. Madam Chair, 1 3. Malaysia recognizes the significance of outer space and the need to protect it in the common interest of all mankind. Malaysia fully recognizes that space science and technology and their application play a significant role in achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. We are hopeful that our exchange of views today could pave the way towards enhancing and raising awareness of the benefits of space activities and tools for the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Sustainable Development Goals. In this regard, Malaysia recognizes the important work of COPOUS and its subcommittees to achieve these goals. 4. Malaysia welcomes the adoption of the Long-Term Sustainability (LTS) guidelines at the 62nd session of COPUOS and the establishment of the new Working Group on LTS. -

General Assembly Distr.: Limited 21 June 2019

United Nations A/AC.105/2019/INF/1 General Assembly Distr.: Limited 21 June 2019 Original: English/French/Spanish Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space Sixty-Second Session Vienna, 12–21 June 2019 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Chair: Mr. André João RYPL Members ALBANIA Head of Delegation H.E. Mr. Igli HASANI, Ambassador, Permanent Representative, Permanent Mission to the United Nations, Vienna Representative Ms. Eni LAMCE, Technical Advisor ALGERIA Chef de la Délégation S.E. Mme. Faouzia MEBARKI, Ambassadrice, Représentante permanente, Mission permanente auprès des Nations Unies, Vienna Représentants M. Karim HOUARI, Directeur d’études en charge à l’Agence Spatiale Algérienne M. Fariz OUTAMAZIRT, Sous-directeur au Service Géographique et Télédétection au Ministère de la défense nationale M. Myriam NAOUN, Attaché des Affaires Etrangères près de l’Ambassade d’Algérie ARGENTINA Jefe de la Delegación S.E. Sr. Rafael Mariano GROSSI, Representante Permanente, Misión Permanente ante las Naciones Unidas, Viena Representante Sr. Lucas MOBRICI, Second Secretary, Misión Permanente ante las Naciones Unidas, Viena Sra. Sandra TORRUSIO, Comisión Nacional de Actividades Espaciales (CONAE) V.19-05117 (E) *1905117* A/AC.105/2019/INF/1 ARMENIA Head of Delegation H.E. Mr. Armen PAPIKYAN, Ambassador, Permanent Representative, Permanent Mission to the United Nations Representatives Ms. Karine KHOUDAVERDIAN, Alternate, Permanent Representative, Permanent Mission to the United Nations, Vienna Mr. Avet POGHOSYAN, Adviser to the Secretary of the Security Council of the of the Staff of the Prime Minister Mr. Vahagn PILIPOSYAN, Counsellor, Permanent Mission to the United Nations, Vienna Ms. Mari AVALYAN, Intern, Permanent Mission to the United Nations, Vienna AUSTRALIA Head of Delegation: H.E. -

APRSAF-21 Reports on Initiatives Kibo-ABC

Session Co-Chairs: Dr. Damrongrit Niammuad (GISTDA/Thailand) Ms. OGAWA Shiho (JAXA/Japan) PARTICIPANTS OF SEUWG 98 participants from 14 countries and region, 44 organizations Country participants Institutes Australia 4 Australian National University, Sydney University Indonesia 6 LAPAN JAXA, JSF, JAMSS, AES, MEXT, Kyushu Institute of Technology, University of Tokyo, Keio University, Nagoya Japan 52 city university, Intercore, Space BD, Astrocean, Human Spaceflight Technology Directorate, Mitsui Bussan Aerospace, SPACETIDE, Ministry of Education, APRSAF Secretariat Malaysia 6 Malaysian Space Agency, Universiti Sains Malaysia Nepal 1 NESARC New Zealand 2 NZSA, ISIS Philippines 5 Philippine Council for Industry, Air Link International Aviation College Singapore 2 SSTA, Zenith Intellutions Taiwan 1 Gran Systems GISTDA, NSTDA, Astroberry Limited, MOBILIFE INTERNATIONAL, Space Zab Company, Defence Technology Thailand 10 Institute, Others Turkey 2 Istanbul Technical University, Belpico Havacilik ve Uzay Teknolojileri ARGE UAE 2 MBRSC USA 3 NASA, Space Generation Advisory Council Vietnam 1 VAST --- 1 UNOOSA 2 Total 98 SEUWG : COUNTRY REPORTS ⚫ Space activities and future plans about Space Environment Utilization were reported from eight countries (Australia, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, Thailand and United Arab Emirates). ➢ Space program ➢ CubeSat development through J-SSOD ➢ Material exposure experiments ➢ “Kibo Robot Programming Challenge” of Kibo-ABC initiative ➢ Conferences, Workshops, and Space science festivals Meeting between NZSA and JAXA in March, 2019 ➢ Commercialization and new projects New Zealand Space Agency and Australian Space Agency participated in KIBO-ABC in September and October, 2019 3 Meeting between ASA and JAXA in March, 2019 “Kibo” Utilization / CubeSat < Achievement in 2019 > ⚫ BIRDS-3 project in 2019 ➢ NepaliSat-1 (the first Nepal satellite) and Raavana-1 (the first Sri Lanka satellite) were deployed from Kibo using J-SSOD in June, 2019. -

Iac-09-B4.1.3 the Evolution of Satellite Programs In

IAC-09-B4.1.3 THE EVOLUTION OF SATELLITE PROGRAMS IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES Danielle Wood Doctoral Student, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA [email protected] Dr. Annalisa Weigel Assistant Professor, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper analyzes the historical paths of eight countries – from Africa, Asia and Latin America – as they pursued technical capability in the area of space technology. Through this analysis, the paper provides three major contributions. The first contribution is an original framework called the Space Technology Ladder. This Ladder framework proffers an idealized path through four major technology categories, as follows: 1) establishing a national space agency; 2) owning and operating a satellite in Low Earth Orbit; 3) owning and operating a satellite in Geostationary Orbit; and 4) launch capability. The second contribution is a graphical timeline, created by mapping the historical achievements of the eight countries onto the Ladder framework. The results provide information about the similarities and differences in the technology strategies of the various countries. The third contribution is a discussion of the strategic decisions faced by the countries under study. By exploring their diverse strategies, we work toward developing prescriptive theory to guide developing country space programs. INTRODUCTION The international space community is the capabilities of their existing space growing. More countries are demonstrating programs to include new capabilities. interest and capability in space. In the beginning of the space era, the funding, This paper considers the policy choices expertise and accomplishments were made by countries as they pursue space dominated by the United States and Soviet activity. -

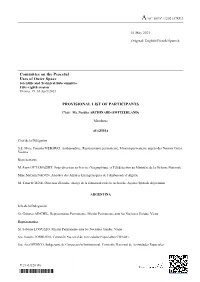

2103220* Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space PROVISIONAL LIST of PARTICIPANTS

A/AC.105/C.1/2021/CRP.2 11 May 2021 Original: English/French/Spanish Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space Scientific and Technical Subcommittee Fifty-eighth session Vienna, 19–30 April 2021 PROVISIONAL LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Chair: Ms. Natália ARCHINARD (SWITZERLAND) Members ALGERIA Chef de la Délégation S.E. Mme. Faouzia MEBARKI, Ambassadrice, Représentante permanente, Mission permanente auprès des Nations Unies, Vienna Représentants M. Fariz OUTAMAZIRT, Sous-directeur au Service Géographique et Télédétection au Ministère de la Défense Nationale Mme Myriam NAOUN, Attachée des Affaires Etrangères près de l’Ambassade d’Algérie M. Tahar IFTENE, Directeur d'Etudes, chargé de la formation et de la recherche, Agence Spatiale Algérienne ARGENTINA Jefe de la Delegación Sr. Gustavo AINCHIL, Representante Permanente, Misión Permanente ante las Naciones Unidas, Viena Representantes Sr. Fabiana LOGUZZO, Misión Permanente ante las Naciones Unidas, Viena Sra. Sandra TORRUSIO, Comisión Nacional de Actividades Espaciales (CONAE) Sra. Ana MEDICO, Subgerente de Cooperación Institucional, Comisión Nacional de Actividades Espaciales. V.21-03220 (E) *2103220* A/AC.105/C.1/2021/CRP.2 Sr. Marcelo COLAZO, Responsable Área de Estudios Ultraterrestres, Comisión Nacional de Actividades Espaciales. Sra. Ximena PORCASI, Comisión Nacional de Actividades Espaciales. Sra. Patricio URUEÑA PALACIO, Misión Permanente ante las Naciones Unidas, Viena ARMENIA Representatives Mr. Ashot HOVSEPYAN, Chief Specialist, Scientific-Technical Department, Ministry of High-Tech Industry, Republic of Armenia Mr. Ararat SAHAKYAN, Chief Specialist, Market Research Division, Market Development Department, Ministry of High-Tech Industry, Republic of Armenia Ms. Elen HARUTYUNYAN, Counsellor, Permanent Mission to the United Nations, Vienna Mr. Davit MANUKYAN, Second Secretary, Permanent Mission to the United Nations, Vienna AUSTRALIA Representatives Mr. -

English Only

A/AC.105/C.2/2021/CRP.7 31 May 2021 English only Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space Legal Subcommittee Sixtieth session Vienna, 31 May–11 June 2021 Item 7 of the provisional agenda* National space legislation Membership of the Report on the status of the national space legislation of countries of the Asia-Pacific Regional Space Agency Forum National Space Legislation Initiative Note by the Secretariat The present information contains a list of participating organizations and members to the work of National Space Legislation Initiative (as of the submission of the report at the end of March 2021) in relation to the Report on the Status of the National Space Legislation of Countries of the Asia-Pacific Regional Space Agency Forum (APRSAF) National Space Legislation Initiative (NSLI) (A/AC.105/C.2/L.318), a Working paper submitted by Australia, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, the Philippines, the Republic of Korea, Thailand, and Viet Nam. __________________ * A/AC.105/C.2/L.317. V.21-03810 (E) *2103810* A/AC.105/C.2/2021/CRP.7 Membership (participating organization, member list) [Original: English] [Received on 9 April 2021] Australia Alexandra Seneta, Executive Director, Office of the Space Regulator, Australian Space Agency (ASA) Michael Cook, Assistant Manager, Office of the Space Regulator, Australian Space Agency (ASA) Karl Rodrigues, Executive Director, National and International Engagement, Australian Space Agency (ASA) Georgia Weinert, Policy Officer, Office of the Space Regulator, Australian Space Agency (ASA) India -

Request for Information (Rfi) Malaysian Earth Observation Satellite Program

MALAYSIAN SPACE AGENCY (MYSA) MINISTRY OF SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION (MOSTI) No. 13, Jalan Tun Ismail 50480 KUALA LUMPUR, MALAYSIA. REQUEST FOR INFORMATION (RFI) MALAYSIAN EARTH OBSERVATION SATELLITE PROGRAM Request for Information Malaysian Earth Observation Satellite Program Table of Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Eligibility and Qualifications 3 3. Project Scope & Requirement 3 3.1. Project Scope 3 3.2. Project Requirement 3 3.3. Financial Requirement 4 4. Request for Information (RFI) Submission Format 5 5. Inquiry 5 APPENDIX 1 6 APPENDIX 2 7 Page 2 of 7 Request for Information Malaysian Earth Observation Satellite Program Introduction The Government of Malaysia intends to embrace partnerships to achieve its strategic goals in expanding its capabilities and opportunities in space. The Government is seeking information under this Request For Information (RFI) to gather and assess the industry’s availability and capabilities to provide satellite technologies via a Public Private Partnership (PPP) that can bring benefits to both the commercial and government sectors. This document is for information and planning purposes only. This RFI does not commit the Government of Malaysia to a binding contract for any supply or service whatsoever. All costs associated with the preparation and submission of the proposal for this RFI shall be borne by the respondents, and the Government will in no case be responsible or liable for these costs, regardless of the conduct or outcome of the RFI process. 1. Eligibility and Qualifications Proposals submitted under this RFI is open to all interested parties, including but not limited to satellite manufactures, satellite operators, industries and investors that have the capability to fulfil the requirements. -

Fulbright Forma 03.15 .Pages

Richard D. Fleeter, PhD Curriculum Vitae EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND 1981 Brown University, Providence, RI PhD Engineering specialization in Thermodynamics and Fluid Mechanics 1978 Stanford University, Stanford, CA, MSc Aerospace Engineering specialization in guidance and control 1976 Brown University, Providence RI AB Engineering / Ecnomics 1. WORK EXPERIENCE - La Sapienza, Rome, Italy (2008 - Present) visiting professor Aerospace design. Teaching responsibilities include Immersive program for Masters candidates including supervision of 6- month long thesis program in spacecraft design. - Brown University, Providence, RI (2001 - Present) Adjunct Associate Professor of Engineering (aerospace systems design, innovation and design), responsible for senior capstone design course for mechanical engineers, created and teach two freshman seminars for engineers and non-engineers on design and innovation. Since 2006 head the Brown Engineering Alumni Medal nominating committee. Since 2009 creator and head of annual Space Horizons conference at Brown university with partial sponsorship by Brown and NASA Space Grant. Head the Equisat nanosatellite student development team since its inception in 2011 with its first NASA-sponsored launch in 2017 - Extraterrestrial Essentials, Charlestown, Rhode Island (2008 - Present) proprietor: provides aerospace consulting and instructional services to clients including Italian Space Agency (2008 through 2012), Japanese Space Agency (JAXA) in consulting. Courses provided at space agencies including NASA (at numerous NASA centers), JAXA, Canadian Space Agency, European Space Agency, Israeli Space Agency, Malaysian Space Agency, US Air Force at Space Command and Air Force Research Lab - AeroAstro, Ashburn, Virginia (1988 - 2008) Founder, CEO and board member, staff of 85 employees and approximately 15 consultants in three US offices: microspacecraft and spacecraft components design, build and operation.