Literature Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Varieties of Modernist Dystopia

Towson University Office of Graduate Studies BETWEEN THE IDEA AND THE REALITY FALLS THE SHADOW: VARIETIES OF MODERNIST DYSTOPIA by Jonathan R. Moore A thesis Presented to the faculty of Towson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Department of Humanities Towson University Towson, Maryland 21252 May, 2014 Abstract Between the Idea and the Reality Falls the Shadow: Varieties of Modernist Dystopia Jonathan Moore By tracing the literary heritage of dystopia from its inception in Joseph Hall and its modern development under Aldous Huxley, George Orwell, Samuel Beckett, and Anthony Burgess, modern dystopia emerges as a distinct type of utopian literature. The literary environments created by these authors are constructed as intricate social commentaries that ridicule the foolishness of yearning for a leisurely existence in a world of industrial ideals. Modern dystopian narratives approach civilization differently yet predict similarly dismal limitations to autonomy, which focuses attention on the individual and the cultural crisis propagated by shattering conflicts in the modern era. During this era the imaginary nowhere of utopian fables was infected by pessimism and, as the modern era trundled forward, any hope for autonomous individuality contracted. Utopian ideals were invalidated by the oppressive nature of unbridled technology. The resulting societal assessment offers a dark vision of progress. iii Table of Contents Introduction: No Place 1 Chapter 1: Bad Places 19 Chapter 2: Beleaguered Bodies 47 Chapter 3: Cyclical Cacotopias 72 Bibliography 94 Curriculum Vitae 99 iv 1 Introduction: No Place The word dystopia has its origin in ancient Greek, stemming from the root topos which means place. -

Dictionary Uncovering the Origins and True Meanings of Business Speak

The Dictionary Uncovering the Origins and True Meanings of Business Speak BOB WILTFONG TIM ITO More Praise for The BS Dictionary “When I worked with Bob Wiltfong at The Daily Show it was clear he was full of BS. I’m glad to see he’s found an outlet for it.” —Stewart Bailey, Former Co-Executive Producer, The Daily Show with Jon Stewart “This is the book I wish I had written.” —Tripp Crosby (of Tripp & Tyler), Entertainers and Creators of “A Conference Call in Real Life” “As a corporate executive, I thought I understood all the business jargon known to (wo)man. But no BS, this dictionary has shown me I’ve only scratched the surface. I’m now on a mission to push the envelope and circle back to this hilari- ous, sometimes cringe-inducing book again and again whenever I need a magic bullet for corporate translation.” —Christine Walters, Television Development Executive “Page-turner is not a word I would normally associate with a dictionary, but this book is just that. It is filled with one delicious entry after another, giving insight into some of the most commonly used business words and phrases in today’s corporate world. At Four Day Weekend, we have taught thousands of business leaders the power of ‘yes, and’ at their jobs. I say ‘yes, and’ to another volume of The BS Dictionary!” —David Ahearn, Co-Founder, Four Day Weekend Comedy “I referred to Bob Wiltfong’s Daily Show field pieces to learn how to do the job. I’m glad he wrote a book I can use to finally figure out what the hell everyone in the office is saying.” —Ronny Chieng, Standup Comedian and Reporter, The Daily Show with Trevor Noah “The BS Dictionary is a cross between an old school dictionary and an Urban Dictionary, with a huge dose of biting personality. -

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Joesell Radford, BA Graduate Program in Education The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Professor Beverly Gordon, Advisor Professor Adrienne Dixson Copyrighted by Crystal Joesell Radford 2011 Abstract This study critically analyzes rap through an interdisciplinary framework. The study explains rap‟s socio-cultural history and it examines the multi-generational, classed, racialized, and gendered identities in rap. Rap music grew out of hip-hop culture, which has – in part – earned it a garnering of criticism of being too “violent,” “sexist,” and “noisy.” This criticism became especially pronounced with the emergence of the rap subgenre dubbed “gangsta rap” in the 1990s, which is particularly known for its sexist and violent content. Rap music, which captures the spirit of hip-hop culture, evolved in American inner cities in the early 1970s in the South Bronx at the wake of the Civil Rights, Black Nationalist, and Women‟s Liberation movements during a new technological revolution. During the 1970s and 80s, a series of sociopolitical conscious raps were launched, as young people of color found a cathartic means of expression by which to describe the conditions of the inner-city – a space largely constructed by those in power. Rap thrived under poverty, police repression, social policy, class, and gender relations (Baker, 1993; Boyd, 1997; Keyes, 2000, 2002; Perkins, 1996; Potter, 1995; Rose, 1994, 2008; Watkins, 1998). -

Construing the Elaborate Discourse of Thomas More's Utopia

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2006 Irony, rhetoric, and the portrayal of "no place": Construing the elaborate discourse of Thomas More's Utopia Davina Sun Padgett Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Padgett, Davina Sun, "Irony, rhetoric, and the portrayal of "no place": Construing the elaborate discourse of Thomas More's Utopia" (2006). Theses Digitization Project. 2879. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2879 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IRONY, RHETORIC, AND THE PORTRAYAL OF "NO PLACE" CONSTRUING THE ELABORATE DISCOURSE OF THOMAS MORE'S UTOPIA A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English Composition by Davina Sun Padgett June 2006 IRONY,'RHETORIC, AND THE PORTRAYAL OF "NO PLACE": CONSTRUING THE ELABORATE DISCOURSE OF THOMAS MORE'S UTOPIA A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Davina Sun Padgett June 2006 Approved by: Copyright 2006 Davina Sun Padgett ABSTRACT Since its publication in 1516, Thomas More's Utopia has provoked considerable discussion and debate. Readers have long grappled with the implications of this text in order to determine the extent to which More's imaginary island-nation is intended to be seen as a description of the ideal commonwealth. -

Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 12-2016 Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Elrick, Kathy, "Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News" (2016). All Dissertations. 1847. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1847 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IRONIC FEMINISM: RHETORICAL CRITIQUE IN SATIRICAL NEWS A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Rhetorics, Communication, and Information Design by Kathy Elrick December 2016 Accepted by Dr. David Blakesley, Committee Chair Dr. Jeff Love Dr. Brandon Turner Dr. Victor J. Vitanza ABSTRACT Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News aims to offer another perspective and style toward feminist theories of public discourse through satire. This study develops a model of ironist feminism to approach limitations of hegemonic language for women and minorities in U.S. public discourse. The model is built upon irony as a mode of perspective, and as a function in language, to ferret out and address political norms in dominant language. In comedy and satire, irony subverts dominant language for a laugh; concepts of irony and its relation to comedy situate the study’s focus on rhetorical contributions in joke telling. How are jokes crafted? Who crafts them? What is the motivation behind crafting them? To expand upon these questions, the study analyzes examples of a select group of popular U.S. -

2019 Study Schedule for Aldous Huxley's Brave New World

2019 Study Schedule for Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World AP Lit & Comp/Fulton Friday, March 29: Intro notes/discussion. Over the weekend, read chapters 1-2 (pp. 3-29). These two chapters, as well as chapter 3, provide basic exposition, describe the setting, and introduce some of the major characters. In your reading journal for chapters 1-2, make two columns. On the left, use your own words to write observations/descriptions of the aspects of setting and characters that you think are significant; on the right side, write down key words and phrases from the text (in quotation marks) that provide evidence of those observations/descriptions. Include the page number for each piece of directly quoted material. Due Monday. Monday, April 1: Share reading journal notes on exposition, including setting and characters. We will begin reading chapter 3 (pp. 30-56) in class, and you will need to finish it at home. Chapter 3 is a continuation of exposition, taken outdoors. Rising action begins when the students and the D.H.C. encounter Mustapha Mond. From this point onward, the omniscient narrator alternates bits of different scenes and conversations to show that they are occurring simultaneously. In your reading journal, decide on and write a title for each of the different conversations (how many are there??). Below each title, write a one to two sentence summary of that particular conversation. What is the purpose of juxtaposing these conversations in this way? Explain. Due Tuesday. Tuesday, 4/2 & Wednesday 4/3: Discuss chapter 3, focusing on the purpose of the juxtaposition of the various scenes depicted. -

Stand-Up Comedy and the Clash of Gendered Cultural Norms

Stand-up Comedy and the Clash of Gendered Cultural Norms The Honors Program Honors Thesis Student’s Name: Marlee O’Keefe Faculty Advisor: Amber Day April 2019 Table of Contents ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................................. 1 LITERATURE REVIEW.......................................................................................................... 2 COMEDY THEORY LITERATURE REVIEW .................................................................. 2 GENDER THEORY LITERATURE REVIEW ................................................................... 7 GENDERED CULTURAL NORMS ...................................................................................... 13 COMEDY THEORY BACKGROUND ................................................................................. 13 COMEDIANS ......................................................................................................................... 16 STEREOTYPES ..................................................................................................................... 20 STAND-UP SPECIALS/TYPES OF JOKES ......................................................................... 25 ROLE REVERSAL ............................................................................................................. 25 SARCASAM ....................................................................................................................... 27 CULTURAL COMPARISON: EXPECTATION VERSUS REALITY ........................... -

Predicting Elections from Politicians' Faces

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Marketing Papers Wharton Faculty Research June 2008 Predicting Elections from Politicians' Faces J. Scott Armstrong University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Kesten C. Green Monash University Randall J. Jones Jr. University of Central Oklahoma Malcolm Wright University of South Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/marketing_papers Recommended Citation Armstrong, J. S., Green, K. C., Jones, R. J., & Wright, M. (2008). Predicting Elections from Politicians' Faces. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/marketing_papers/136 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/marketing_papers/136 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Predicting Elections from Politicians' Faces Abstract Prior research found that people's assessments of relative competence predicted the outcome of Senate and Congressional races. We hypothesized that snap judgments of "facial competence" would provide useful forecasts of the popular vote in presidential primaries before the candidates become well known to the voters. We obtained facial competence ratings of 11 potential candidates for the Democratic Party nomination and of 13 for the Republican Party nomination for the 2008 U.S. Presidential election. To ensure that raters did not recognize the candidates, we relied heavily on young subjects from Australia and New Zealand. We obtained between 139 and 348 usable ratings per candidate between May and August 2007. The top-rated candidates were Clinton and Obama for the Democrats and McCain, Hunter, and Hagel for the Republicans; Giuliani was 9th and Thompson was 10th. At the time, the leading candidates in the Democratic polls were Clinton at 38% and Obama at 20%, while Giuliani was first among the Republicans at 28% followed by Thompson at 22%. -

George Orwell's Down and out in Paris and London

/V /o THE POLITICS OF POVERTY: GEORGE ORWELL'S DOWN AND OUT IN PARIS AND LONDON THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For-the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Marianne Perkins, B.A. Denton, Texas May, 1992 Perkins, Marianne, The Politics of Poverty: George Orwell's Down and Out in Paris and London. Master of Arts (Literature), May, 1992, 65 pp., bibliography, 73 titles. Down and Out in Paris and London is typically perceived as non-political. Orwell's first book, it examines his life with the poor in two cities. Although on the surface Down and Out seems not to be about politics, Orwell covertly conveys a political message. This is contrary to popular critical opinion. What most critics fail to acknowledge is that Orwell wrote for a middle- and upper-class audience, showing a previously unseen view of the poor. In this he suggests change to the policy makers who are able to bring about improvements for the impoverished. Down and Out is often ignored by both critics and readers of Orwell. With an examination of Orwell's politicizing background, and of the way he chooses to present himself and his poor characters in Down and Out, I argue that the book is both political and characteristic of Orwell's later work. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. ORWELL'S PAST AND MOTIVATION. ......... Biographical Information Critical Reaction Comparisons to Other Authors II. GIVING THE WEALTHY AN ACCURATE PICTURE ... .. 16 Publication Audience Characters III. ORWELL'S FUTURE INFLUENCED BY HIS PAST... -

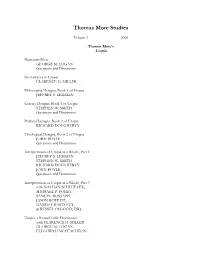

Thomas More Studies 1 (2006) 3 Thomas More Studies 1 (2006) George M

Thomas More Studies Volume 1 2006 Thomas More’s Utopia Humanist More GEORGE M. LOGAN Questions and Discussion No Lawyers in Utopia CLARENCE H. MILLER Philosophic Designs, Book 1 of Utopia JEFFREY S. LEHMAN Literary Designs, Book 1 of Utopia STEPHEN W. SMITH Questions and Discussion Political Designs, Book 2 of Utopia RICHARD DOUGHERTY Theological Designs, Book 2 of Utopia JOHN BOYLE Questions and Discussion Interpretation of Utopia as a Whole, Part 1 JEFFREY S. LEHMAN STEPHEN W. SMITH RICHARD DOUGHERTY JOHN BOYLE Questions and Discussion Interpretation of Utopia as a Whole, Part 2 with NATHAN SCHLUETER, MICHAEL P. FOLEY, SAMUEL BOSTAPH, JASON BOFETTI, GABRIEL BARTLETT, & RUSSEL OSGOOD, ESQ. Utopia, a Round Table Discussion with CLARENCE H. MILLER GEORGE M. LOGAN ELIZABETH MCCUTCHEON The Development of Thomas More Studies Remarks CLARENCE H. MILLER ELIZABETH MCCUTCHEON GEORGE M. LOGAN Interrogating Thomas More Interrogating Thomas More: The Conundrums of Conscience STEPHEN D. SMITH, ESQ. Response JOSEPH KOTERSKI, SJ Reply STEPHEN D. SMITH, ESQ. Questions and Discussion Papers On “a man for all seasons” CLARENCE H. MILLER Sir Thomas More’s Noble Lie NATHAN SCHLUETER Law in Sir Thomas More’s Utopia as Compared to His Lord Chancellorship RUSSEL OSGOOD, ESQ. Variations on a Utopian Diversion: Student Game Projects in the University Classroom MICHAEL P. FOLEY Utopia from an Economist’s Perspective SAMUEL BOSTAPH These are the refereed proceedings from the 2005 Thomas More Studies Conference, held at the University of Dallas, November 4-6, 2005. Intellectual Property Rights: Contributors retain in full the rights to their work. George M. Logan 2 exercises preparing himself for the priesthood.”3 The young man was also extremely interested in literature, especially as conceived by the humanists of the period. -

FOX News/Opinion Dynamics Poll 10 January 08

FOX News/Opinion Dynamics Poll 10 January 08 Polling was conducted by telephone January 9, 2008, in the evening. The total sample is 500 likely Republican primary voters in South Carolina with a margin of error of ±4%. Respondents were randomly selected from two sources: 250 were randomly selected from a list of voters who had previously voted in a South Carolina Republican primary, and 250 were drawn from a random digit dial sample which gives every household in the state an equal chance of being called. All respondents were screened to ensure that they are registered to vote in South Carolina and likely to vote in the 2008 Republican primary. 1. I’m going to read you a list of candidates. If the South Carolina Republican presidential primary were held today, would you vote for...? (ROTATE CHOICES) 9 Jan 08 1-3 Apr 07 John McCain 25% 25% Mike Huckabee 18 2 Mitt Romney 17 14 Fred Thompson 9 2* Rudy Giuliani 5 26 Ron Paul 5 1 Duncan Hunter 1 1 (Newt Gingrich – vol.) na 5* Sam Brownback na 2 Tommy Thompson na 2 Jim Gilmore na 1 Tom Tancredo na 1 (Other) 1 1 (Don’t know) 19 16 *responses were volunteered in April 2. Are you certain to support that person or do you think you may change your mind and support someone else in the 2008 South Carolina presidential primary? Certain to support May change mind (Don’t know) 9 Jan 08 58% 40 1 McCain supporters 58% 41 2 Romney supporters 57% 42 1 Huckabee supporters 60% 38 2 1-3 Apr 07 30% 62 8 McCain supporters 30% 62 8 Romney supporters 20% 73 8 3. -

Is Calm in City As Scene Is

•9") f : S ; r #iHlife,;3A: ^^^'^'^is^^'u'k^Jlaiii 5i;i*r; ;$?;. ;--S?^V:^l^ ^^1^^^4^8¾¾¾^^¾½^^¾¾¾ -.^-^:-¾¾^ ? ^. ' '-v^>. ^ V.->^->i^.-?. ;i ; : •vW"-j.-':'-i:^r-VH _4.vt.^n :-^r m ,--.v<^ '£tm £^^£^££^£^12,22^¾¾¾^^¾.^^ ^M« » -.-1-. t Volume 19' Number 46 Thursday, December t, 1983 ' Westland, Michigan 48 Pages Twenty-five cents *%^}W®S MzMmmMmM^MMMMmi ftjL^vrtifSJSa^ All is calm in city as scene is By 8«ndr« Arm brut t«f PLYMOUTH has a city NaUvity the Oakland County ACLU and a plain editor scene located in Kellogg Park, and tiff in the Oak Park suit. Wayne has a Nativity scene on the The Wayne-Westland School District Westland's Nativity scene was being grounds of the library. Garlands and has an American Indian education pro erected on City Hall grounds Tuesday lanterns also are being strung along gram, and there is a small Arabic com despite several pending lawsuits which Simms Instead of Michigan Ave., this munity in Westland. .•'; ".• question such displays in other cities. year due to road construction this year. "The Pilgrims came to this country * The Nativity scene in Westland is Wayne will nave its tree lighting at 5 to flee religious persecution. They were part of the annual decorations around p.m. Sunday at the Veterans Peace Me trying to get away from a situation City Hall, Including numerous tree morial. where government favored one religion lights purchased through donations A Wayne department of public ser over another," Fealk said. from city unions and Mayor Charles vice spokeswoman said that the deco •That's where we got this Idea of sep Pickering.