“You Can't See Them, but They're Always There”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

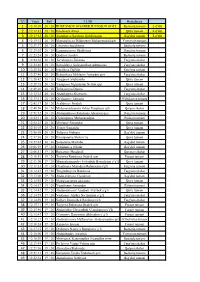

T/R 1 1-O'rin 2 2-O'rin 3 3-O'rin 4 5 6 7

T/r Vaqti Ball F.I.SH Hududingiz 1 12:10:05 20 / 20 RUSTAMOV OG'ABEK ILYOSJON OG'LI Beshariq tumani 1-o'rin 2 12:12:43 20 / 20 Ibrohimov Axror Quva tumani 2-o'rin 3 12:17:33 20 / 20 Xoshimova Sarvinoz Qobiljon qizi Bag'dod tumani 3-o'rin 4 12:19:12 20 / 20 Mamataliyeva Dildoraxon Muhammadali qizi Yozyovon tumani 5 12:21:17 20 / 20 Umarova Sug'diyona Beshariq tumani 6 12:23:02 20 / 20 Egamnazarova Shahloxon Dang'ara tumani 7 12:23:24 20 / 20 Qodirov Javohir Beshariq tumani 8 12:24:38 20 / 20 Jo'raboyeva Zebiniso Farg'ona shahar 9 12:24:46 20 / 20 Sotvoldieva Guloyim Rustambekovna Farg'ona shahar 10 12:25:54 20 / 20 Ismoilova Gullola Farg'ona tumani 11 12:27:46 20 / 20 Bektosheva Mohlaroy Anvarjon qizi Farg'ona shahar 12 12:28:42 20 / 20 Turģunov Shukurullo Quva tumani 13 12:29:18 20 / 20 Yusupova Niginabonu Ne'mat qizi Quva tumani 14 12:29:20 20 / 20 Tohirjonova Diyora Farg'ona shahar 15 12:32:35 20 / 20 Abdullayeva Shaxnoza Farg'ona shahar 16 12:33:31 20 / 20 Qo'chqorov Jahongir O'zbekiston tumani 17 12:43:17 20 / 20 Arabboyev Jòrabek Quva tumani 18 12:48:56 20 / 20 Muhammadjonova Odina Yoqubjon qizi Qo'qon shahar 19 12:51:32 20 / 20 Abdumalikova Ruhshona Abrorjon qizi Dang'ara tumani 20 12:52:11 20 / 20 G'ulomjonov Muhammadjon Rishton tumani 21 12:52:25 20 / 20 Mirzayev Samandar Quva tumani 22 12:55:03 20 / 20 Toirov Samandar Quva tumani 23 12:56:05 20 / 20 Tolipova Gulmira Bag'dod tumani 24 12:57:36 20 / 20 Ikromjonova Shohroʻza Quva tumani 25 12:57:45 20 / 20 Solijonova Marxabo Bag'dod tumani 26 12:06:19 19 / 20 Ochildinova Nilufar -

Les Droits De L'homme En Europe Janv.-Fev. 2017

DROITS DE L’HOMME DANS LE MONDE LES DROITS DE L’HOMME ORIENTALE ET DANS EN EUROPE L’ESPACE POST-SOVIÉTIQUE N° 21 JANV.-FEV. 2017 Éditorial 2016 aura été une année électorale. Aux Etats- dans le Caucase, la Lettre change de nom ! Unis avec la campagne qui a vu Donald Trump Elle s’appelle désormais « Lettre des droits s’imposer au parti républicain ; mais également de l’Homme en Europe orientale et dans avec une série de scrutins législatifs et l’espace post-soviétique ». En effet, l’héritage présidentiels en Europe de l’Est et dans l’ex-bloc soviétique, selon des modalités diverses soviétique. Entre août et novembre, l’Estonie a et les spécificités propres à chaque pays, changé de chef d’État ; le 13 novembre dernier, continue de structurer encore aujourd’hui les Bulgares ont également élu leur président ; le le champ politique de ces territoires. 30 octobre, c’était le tour des Moldaves... Les Changement de nom n’implique pas élections législatives de septembre ont ouverts changement de choix éditoriaux ; nous pour la première fois les portes du Parlement continuerons évidemment à nous à l’opposition au Bélarus et ce même mois focaliser sur l’étude et la défense des les Russes ont confirmé leur adhésion au droits et libertés, plus que jamais au pouvoir en place. Les élections législatives ont coeur des constructions en cours... eu lieu en octobre en Géorgie ; l’Ouzbékistan vient de changer de président en décembre E.T. dernier suite au décès d’Islam Karimov au pouvoir depuis 1991. Quelles leçons retirer de ces consultations ? Nous vous invitons à les découvrir ici en embarquant pour un « voyage » électoral d’Ouest en Est… Et pour acter l’élargissement de notre publication aux contenus portant sur les pays et les territoires faisant partie de l’ex- Union soviétique, situés en Asie centrale et 01 LES DROITS DE L’homme en europe orientALE ET DANS L’espACE POST-SOVIÉTIQUE N° 21 SOMMAIRE Éditorial ..................................................................................................................................................... -

Delivery Destinations

Delivery Destinations 50 - 2,000 kg 2,001 - 3,000 kg 3,001 - 10,000 kg 10,000 - 24,000 kg over 24,000 kg (vol. 1 - 12 m3) (vol. 12 - 16 m3) (vol. 16 - 33 m3) (vol. 33 - 82 m3) (vol. 83 m3 and above) District Province/States Andijan region Andijan district Andijan region Asaka district Andijan region Balikchi district Andijan region Bulokboshi district Andijan region Buz district Andijan region Djalakuduk district Andijan region Izoboksan district Andijan region Korasuv city Andijan region Markhamat district Andijan region Oltinkul district Andijan region Pakhtaobod district Andijan region Khdjaobod district Andijan region Ulugnor district Andijan region Shakhrikhon district Andijan region Kurgontepa district Andijan region Andijan City Andijan region Khanabad City Bukhara region Bukhara district Bukhara region Vobkent district Bukhara region Jandar district Bukhara region Kagan district Bukhara region Olot district Bukhara region Peshkul district Bukhara region Romitan district Bukhara region Shofirkhon district Bukhara region Qoraqul district Bukhara region Gijduvan district Bukhara region Qoravul bazar district Bukhara region Kagan City Bukhara region Bukhara City Jizzakh region Arnasoy district Jizzakh region Bakhmal district Jizzakh region Galloaral district Jizzakh region Sh. Rashidov district Jizzakh region Dostlik district Jizzakh region Zomin district Jizzakh region Mirzachul district Jizzakh region Zafarabad district Jizzakh region Pakhtakor district Jizzakh region Forish district Jizzakh region Yangiabad district Jizzakh region -

Threats and Attacks Against Human Rights Defenders and the Role Of

Uncalculated Risks Threats and attacks against human rights defenders and the role of development financiers Uncalculated Risks Threats and attacks against human rights defenders and the role of development financiers May 2019 This report was authored by With case studies and contributions from And with the generous support of Uncalculated Risks Threats and attacks against human rights defenders and the role of development financiers © Coalition for Human Rights in Development, May 2019 The views expressed herein, and any errors or omissions are solely the author’s. We additionally acknowledge the valuable insights and assistance of Valerie Croft, Amy Ekdawi, Lynne-Samantha Severe, Kendyl Salcito, Julia Miyahara, Héctor Herrera, Spencer Vause, Global Witness, Movimento dos Atingidos por Barragens, and the various participants of the Defenders in Development Campaign in its production. This report is an initiative of the Defenders in Development Campaign which engages in capacity building and collective action to ensure that communities and marginalized groups have the information, resources, protection and power to shape, participate in, or oppose development activities, and to hold development financiers, governments and companies accountable. We utilize advocacy and campaigning to change how development banks and other actors operate and to ensure that they respect human rights and guarantee a safe enabling environment for public participation. More information: www.rightsindevelopment.org/uncalculatedrisks [email protected] This publication is a CC-BY-SA – Attribution-ShareAlike creative commons license – the text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. The license holder requests that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. -

Uzbek President Reins in Security Service

Uzbek President Reins In Security Service Once-mighty intelligence agency weakened by a serious shake-up. Uzbek president Shavkat Mirziyoyev has launched a major reorganisation of the powerful National Security Service (SNB) in what appears to be the most ambitious series of reforms since he took power in December 2016. In mid-March, Mirziyoyev issued a decree slashing the powers of an intelligence agency long seen as a repressive secret police – a month after the resignation of formidable chairman Rustam Inoyatov, who had headed the Uzbek president Shavkat Mirziyoyev. (Photo: Press SNB since 1995. Service of the Uzbek President) Mirziyoyev’s decree transferred responsibility for a range of issues, including the security of state institutions, from SNB to the Interior Ministry (MVD) as of April 1. Other tasks, including building and maintaining security installations, will be transferred to the ministry of defence. The SNB was also renamed the State Security Service (GSB). The president made clear that what he described as the “unjustified expansion” of the agency’s authority would end. In the past, “any local issue could be seen as a national security threat. This reorganisation will draw the attention of the agency to the real state-level threats”. The decree also specifies that the intelligence agencies must “strictly uphold people’s rights, freedoms and legitimate interests” as well as protecting the state from external and Uzbek President Reins In Security Service internal threats. Although the SNB is a large agency with numerous departments throughout the country and an extensive agent network abroad, Mirziyoyev said that its centralised control had “contributed to unjustified intervention in all spheres of the activities of state authorities”. -

From the History of Ancient Cities of the Fergana Valley (In the Example of Mingtepa-Ershi)

European Scholar Journal (ESJ) Available Online at: https://www.scholarzest.com Vol. 2 No. 5, MAY 2021, ISSN: 2660-5562 FROM THE HISTORY OF ANCIENT CITIES OF THE FERGANA VALLEY (IN THE EXAMPLE OF MINGTEPA-ERSHI) Hakimov Abdumuxtor Abduxalimovich Senior Lecturer, Department of History of Uzbekistan, Andijan State University, Doctor of Philosophy in History (PhD) Article history: Abstract: Received: 2th April 2021 This article analyzes the study of data on the cultural history of Mingtepa-Ershi, Accepted: 20th April 2021 an ancient major stage of urbanization in the Fergana Valley, by archaeologists. Published: 9th May 2021 The article also states that the ruins of Mingtepa-Ershi are located on the Great Silk Road and was one of the largest cities in the history of 2,500 years, which made a worthy contribution to the development of world civilization. Keywords: Mingtepa-Ershi, Central Asian civilization, Fergana valley, Pamir-Fergana expedition, Chust culture, Buddha, Afrosiab, Jarqo'ton, Akhsikat, Munchoktepa, Dalvarzintepa, Academy of Material Culture, urbanization In the historiography of the twentieth century, the main factors and stages of development of the process of emergence and formation of cities in the Fergana Valley have not been sufficiently studied. The main reasons for this process are that in many Soviet archeological works (mainly in the works of "central" scholars and some local researchers) the Fergana Valley is described as a periphery, bordering on Central Asian civilizations, and the history of Fergana cities is largely denied. In fact, another scientist from the “center,” Yu.A. Zadneprovsky (Leningrad) promoted the idea that urbanization in the valley began in the late Bronze-Early Iron Age (early I millennium BC) in the 70s of last century and always defended this idea. -

Uzbekistan 2016 Human Rights Report

UZBEKISTAN 2016 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Uzbekistan is an authoritarian state with a constitution that provides for a presidential system with separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. The executive branch under former President Islam Karimov dominated political life and exercised nearly complete control over the other branches of government. On September 2, President Karimov died in office and new elections took place on December 4. Former prime minister Shavkat Mirziyoyev won with 88 percent of the vote. The Organization for Security and Cooperation’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (OSCE/ODHIR), in its preliminary election observation mission report, noted that “limits on fundamental freedoms undermine political pluralism and led to a campaign devoid of genuine competition.” The report also identified positive changes such as the election’s increased transparency, service to disabled voters, and unfettered access for 600 international observers. Civilian authorities generally maintained effective control over the security forces, but security services permeated civilian structures, and their interaction was opaque, which made it difficult to define the scope and limits of civilian authority. The most significant human rights problems included torture and abuse of detainees by security forces, denial of due process and fair trial, and an inability of citizens to choose their government in free, fair, and periodic elections. Other continuing human rights problems included incommunicado and prolonged detention; harsh and sometimes life-threatening prison conditions; arbitrary arrest and detention; and widespread restrictions on religious freedom, including harassment of religious minority group members and continued imprisonment of believers of all faiths. -

Constructing the Uzbek State

Constructing the Uzbek State 17_575_Laruelle.indb 1 11/14/17 2:00 PM CONTEMPORARY CENTRAL ASIA: SOCIETIES, POLITICS, AND CULTURES Series Editor Marlene Laruelle, George Washington University At the crossroads of Russia, China, and the Islamic world, Central Asia re- mains one of the world’s least-understood regions, despite being a significant theater for muscle-flexing by the great powers and regional players. This series, in conjunction with George Washington University’s Central Asia Program, offers insight into Central Asia by providing readers unique access to state-of-the-art knowledge on the region. Going beyond the media clichés, the series inscribes the study of Central Asia into the social sciences and hopes to fill the dearth of works on the region for both scholarly knowledge and undergraduate and graduate student education. Titles in Series Afghanistan and Its Neighbors after the NATO Withdrawal, edited by Amin Saikal and Kirill Nourzhanov Integration in Energy and Transport: Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey, by Alexandros Petersen Kazakhstan in the Making: Legitimacy, Symbols, and Social Changes, edited by Marlene Laruelle The Origins of the Civil War in Tajikistan: “For the Soul, Blood, Homeland, and Honor,” by Tim Epkenhans Rewriting the Nation in Modern Kazakh Literature: Elites and Narratives, by Diana T. Kudaibergenova The Central Asia–Afghanistan Relationship: From Soviet Intervention to the Silk Road Initiatives, edited by Marlene Laruelle Eurasia’s Shifting Geopolitical Tectonic Plates: Global Perspective, Local Theaters, -

Buying Viagra in Denmark

Activity Report Farmers Field Day 31 May 2014: Fergana, Fergana Valley Action Site, Central Asia 11 June 2014: Khujand, Fergana Valley Action Site, Central Asia Organized by CRP Dryland Systems International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas Central Asia and the Caucasus Regional Program Tashkent, Uzbekistan 1 Farmers’ Field Day Action site: Fergana Valley Objectives: • Demonstrate the performance of recently released and pipeline varieties of winter wheat to the men and women farmers, seed producers, extension workers, policy makers and researchers. • Jointly evaluate experimental lines and identify superior lines for further evaluation and release consideration. • Observe, discuss and learn from seed production demonstration plots to produce quality seed. Delivery: (Fergana, Uzbekistan) • Field day was organized in the research, demonstration and seed multiplication plots established under CRP-DS as collaborative activities among ICARDA, research institute, district administration office, and district level department of agriculture in Fergana, Uzbekistan. • The participants were welcome and addressed by Dr. Amir Amanov (Director of Uzbek Research Institute of Plant Industry), Imomaliev Bakhromjon (Head of Fergana region Agriculture and Water Rsources Department), and Dr. Jozef Turok (ICARDA-CAC Regional Coordinator) • The participants were given information about the adaptive trials, varietal demonstration plots and seed production demonstration plots by national wheat research coordinator of Uzbekistan Dr. Amir Amanov -

Month in Review: Central Asia in November 2020

Month in Review: Central Asia in November 2020 November 2020 in Central Asia is remembered for the run-up to the parliamentary elections in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan; high-level official meetings of the SCO and CIS; several protests; appreciating exchange rates and rising food prices; and the tenuous epidemiological situation in the region. The analytical platform CABAR.asia presents a brief overview of the major events in the region over the past month. Follow us on Telegram Kazakhstan General epidemiological situation Kazakhstan’s Health Ministry says that the number of coronavirus cases in November nearly quadrupled compared to last month. According to the President of Kazakhstan Kassym Zhomart-Tokayev, several regions of the country had been hiding the real extent of the coronavirus outbreak. The media also report a staggering death toll. On November 16, the country’s Health Minister stressed increase in maternal mortality over the last three months. Moreover, there has been coronavirus contagion among school-aged children. As of November 30, Kazakhstan reports a total number of 132,348 coronavirus cases and 1,990 deaths. Kazakh Health Ministry has detached pneumonia data from tallying COVID-19 numbers since August 1, 2020. As of November 30, the country reports a total of 42,147 cases of pneumonia and 443 deaths. Tightening quarantine measures The epidemiological situation in Kazakhstan has been rather tenuous over this month. Month in Review: Central Asia in November 2020 Apart from East Kazakhstan and North Kazakhstan, Pavlodar, Kostanay, and Akmola regions were assigned red labeling. The cities of Nursultan and Almaty, along with the West Kazakhstan region are in the yellow zone. -

Download This Article in PDF Format

E3S Web of Conferences 258, 06068 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202125806068 UESF-2021 Possibilities of organizing agro-touristic routes in the Fergana Valley, Uzbekistan Shokhsanam Yakubjonova1,*, Ziyoda Amanboeva1, and Gulnaz Saparova2 1Tashkent State Pedagogical University, Bunyodkor Road, 27, Tashkent, 100183, Uzbekistan 2Tashkent State Agrarian University, University str., 2, Tashkent province, 100140, Uzbekistan Abstract. The Fergana Valley, which is rich in nature and is known for its temperate climate, is characterized by the fact that it combines many aspects of the country's agritourism. As a result of our research, we have identified the Fergana Valley as a separate agro-tourist area. The region is rich in high mountains, medium mountains, low mountains (hills), central desert plains, irrigated (anthropogenic) plains, and a wide range of agrotouristic potential and opportunities. The creation and development of new tourist destinations is great importance to increase the economic potential of the country. This article describes the possibilities of agrotourism of the Fergana valley. The purpose of the work is an identification of agro-tours and organization of agro-tourist routes on the basis of the analysis of agro-tourism potential and opportunities of Fergana agro-tourist region. 1 Introduction New prospects for tourism are opening up in our country, and large-scale projects are being implemented in various directions. In particular, in recent years, new types of tourism such as ecotourism, agrotourism, mountaineering, rafting, geotourism, educational tourism, medical tourism are gaining popularity [1-4]. Today, it is important to develop the types of tourism in the regions by studying their tourism potential [1, 3]. -

The Terrorist Threat and Security Sector Reform in Central Asia: the Uzbek Case

Peter K. Forster THE TERRORIST THREAT AND SECURITY SECTOR REFORM IN CENTRAL ASIA: THE UZBEK CASE Introduction "At Istanbul, we will enhance our Partnerships to deliver more. We will concentrate more on defence reform to help some of our partners continue with their democratic transitions. We will also focus on increasing our co- operation with the Caucasus and Central Asia – areas that once seemed very far away, but that we now know are essential to our security right here." - NATO Secretary General, Jaap de Hoop Scheffer June 2004. NATO Secretary General Jaap de Hoop Scheffer comments speak not only to an increased awareness in NATO and the West of the importance of Central Asia but also illustrate the importance of security sector reform as a component of the democratization process. The responsiveness of the security sector to reforms that inculcate civil and ultimately democratic control procedures is a measure of a state’s progress toward democratization. Notwithstanding, it is widely admitted that there is no commonality among security sector reform. The security sector encompasses all state institutions that have a formal mandate to ensure the safety of a state and its citizens against violence and coercion. However, it may also include non-government armed political action 227 groups.98 This study will assess the level of security sector reform within those organizations that traditionally have held the state’s monopoly on the use of force, the military and the internal state security apparatus.99 The progress in security sector reform is dependent, to varying degrees, upon a state’s past experiences, both cultural and taught, the domestic relationship between society and the security sector including how of the state’s military and internal security forces developed, and the geo- political conditions under which reform currently is occurring including the influence of foreign countries.