Morrison Dissertation Final Submission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trailblazer GNICUDORTNI Trailblazer Trailblazer Stfieneb & Skrep Rof Ruo Srebircsbus

The Sentinel The Sentinel The Sentinel Stress Free - Sedation Dentistr y September 14 - 20, 2019 tvweekSeptember 14tv - 20, 2019 week tvweekSeptember 14 - 20,George 2019 Blashford,Blashford, DMD 35 Westminster Dr. Carlisle (717) 243-2372 www.blashforddentistry.com Trailblazer INTRODUCING Trailblazer Trailblazer Benefits & Perks For Our Subscribers Introducing News+ Membership, a program for our Lilly Singh hosts “A Little subscribers, dedicated to ooering perks and benefits taht era Lilly Singh hosts “A Little Late With Lilly Singh” only available to you as a member. News+ Members will Late With Lilly Singh” continue to get the stories and information that makes a Lilly Singh hosts “A Little dioerence to them, plus more coupons, ooers, and perks taht Late With Lilly Singh” only you as a member nac .teg COVER STORY / CABLE GUIDE ...............................................2 COVER STORY / CABLE GUIDE ...............................................2 SUDOKUGiveaways / VIDEO RSharingELEASES ..................................................Events Classifieds Deals Plus More8 SCUDOKUROSSWORD / VIDEO .................................................................... RELEASES ..................................................83 CROSSWORD ....................................................................3 WORD SEARCH...............................................................16 CWOVERSPORTSORD STORY S...........................................................................EARCH / C...............................................................ABLE -

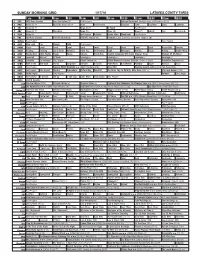

Sunday Morning Grid 1/17/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/17/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan State at Wisconsin. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Clangers Luna! LazyTown Luna! LazyTown 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Liberty Paid Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Seattle Seahawks at Carolina Panthers. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Cook Moveable Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Raggs Space Edisons Travel-Kids Soulful Symphony With Darin Atwater: Song Motown 25 My Music 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Pumas vs Toluca República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Race to Witch Mountain ›› (2009, Aventura) (PG) Zona NBA Treasure Guards (2011) Anna Friel, Raoul Bova. -

Daisy Take Action Requirements the Daisy Outdoor Journey Consists of Two Badges—Outdoor Art Maker, Buddy Camper—And Three Take Action Meetings

Take Action Outdoor 1 Overview Note to Volunteers: Daisy Take Action Requirements The Daisy Outdoor Journey consists of two badges—Outdoor Art Maker, Buddy Camper—and three Take Action meetings. To complete the Journey, have girls complete the meetings in the following order: • Outdoor Art Maker badge (2 meetings) • Buddy Camper badge (2 meetings) • Take Action (3 meetings) Girls must complete a Take Action project at the end of the Daisy Outdoor Journey. Get Help for Take Action There are three Take Action meetings—one for planning, one for creating and carrying out a project, and one for awards and celebration. Look for this helpful Take Action Guide in the Meeting Aids resources section: • Girl Scout Volunteer Take Action Guide: Find out the difference between community service and a Take Action project, steps for a Take Action project, how to make a project sustainable, and ways girls can Take Action. Make the Most of the Take Action Meetings Use the talking points (but make them your own): In each session, you’ll find suggested talking points under the heading “SAY.” Some volunteers, especially new ones, find it helpful to follow the script. Others use the talking points as a guide and deliver the information in their own words. Either way is just fine. Add an extra meeting: The meetings are each designed for 60 minutes. It’s perfectly OK to add a meeting to your Outdoor Journey plan if you feel girls need more time completing the Take Action project. Use Girl Scouts’ three processes: Girl-Led, Learning By Doing, Cooperative Learning—these three processes are the key to making sure girls have fun in Girl Scouts and keep coming back. -

Jahrescharts 2019

JAHRESCHARTS 2019 TOP 200 TRACKS PEAK ARTIST TITLE LABEL/DISTRIBUTOR POSITION 01 DJ Khaled Ft. SZA Just Us We The Best/Epic/Sony 01 02 Chris Brown Undecided RCA/Sony 01 03 Blueface Ft. Cardi B. & YG Thotiana (Remix) Fifth Amendment/eOne 01 04 DJ ClimeX Ft. Nantaniel & Nolay Baila ClimeX Entertainment 01 05 Gang Starr Ft. J. Cole Family And Loyalty Gang Starr Enterprises 01 06 Tyga Ft. G-Eazy & Rich The Kid Girls Have Fun Last Kings/Empire 01 07 Major Lazer Ft. J Balvin & El Alfa Que Calor Mad Decent/Because/Caroline/Universal 01 08 Marshmello Ft. Tyga & Chris Brown Light It Up Joytime Collective/RCA/Sony 02 09 Ed Sheeran & Travis Scott Antisocial Asylum/Atlantic UK/WMI/Warner 02 10 DJ Spanish Fly Ft. Señorita Bailemos Major Promo Music 03 11 Chris Brown Ft. Nicki Minaj & G-Eazy Wobble Up RCA/Sony 01 12 Cardi B Ft. Bruno Mars Please Me Atlantic/WMI/Warner 01 13 Chris Brown Ft. Drake No Guidance RCA/Sony 03 14 DJ ClimeX Ft. Michael Rankiao & Öz Fuego ClimeX Entertainment 01 15 Snoop Dogg Ft. Chris Brown Turn Me On Doggystyle/Empire 01 16 Culcha Candela Ballern Culcha Sound/The Orchard 03 17 Seeed G€LD Seeed/BMG Rights/ADA 03 18 French Montana Ft. City Girls Wiggle It Epic/Sony 01 19 DJ Mustard & Migos Pure Water 10 Summers/UMI/Universal 03 20 Apache 207 Roller TwoSides/Four Music/Sony 04 21 Lil Pump Ft. Lil Wayne Be Like Me Warner Bros./WMI/Warner 04 22 Nicki Minaj Megatron Young Money/Cash Money/UMI/Universal 01 23 Travis Scott Highest In The Room Epic/Sony 03 24 Gesaffelstein & The Weeknd Lost In The Fire Columbia/Sony 03 25 Ardian Bujupi & Farruko Ft. -

Volunteer Essentials 2020–2021

Volunteer Essentials 2020–2021 Copyright 2009–2020 © Copyright 2009–2020 Girl Scouts of the United States of America. All rights reserved. All information and material contained in the Girl Scouts Volunteer Essentials Guide (“Material”) is provided by the Girl Scouts of the United States of America (GSUSA) and is intended to be educational material solely to be used by Girl Scouts volunteers and council staff. Reproduction, distribution, compiling or creating derivative works of any portion of the Material or any other use other than noncommercial uses as permitted by copyright law is prohibited, unless explicit, prior authorization by GSUSA in writing was granted. GSUSA reserves its exclusive right in its sole discretion to alter, limit or discontinue the Material, at any time without notice. Page 1 | 66 Adventure Ahead! Welcome to the great adventure that is Girl Scouting! Thanks to volunteers and mentors like you, generations of girls have learned to be leaders in their own lives and in the world. Have no doubt: you, and nearly a million other volunteers like you, are helping girls make a lasting impact on the world. And we thank you from the bottom of our hearts! This guide, Volunteer Essentials, is designed to support busy troop volunteers on the go. You can easily find what you need to get started on your Girl Scout journey and search for answers throughout the troop year. Get started by browsing through these sections: • All About Girl Scouts • Engaging Girls & Engaging Families • Troop Management • Product Program • Troop Finances • Safety • Returning to In-Person Troop Meetings and Activities: Interim COVID-19 Guidance for Volunteers New troop leader? We’ve got you covered. -

Running Down a Dream—2017 NFR Field Set by Tanya Randall Bean Will Still Be One to Watch in De- Everyone Knew That the Wrangler Cember However

OCTOBER 3, 2017 Volume 11: Issue 40 In this issue... • Grid Iron Futurity, pg 22 • BBR Territorials, pg 31 • Qualifier #18 & #19, pg 32 • Ardmore Futurity, pg 38 • Jud Little Ranch Sale, pg 41 fast horses, fast news • West Fest, pg 42 Published Weekly Online at www.BarrelRacingReport.com - Since 2007 Running Down A Dream—2017 NFR Field Set By Tanya Randall Bean will still be one to watch in De- Everyone knew that the Wrangler cember however. She has her talented 4-year-old Champions Challenge Finale in Sioux 2017 WORLD STANDINGS TR Dollysfamousdash (by Dash Ta Fame out of Falls, S.D., would greatly impact the race As of Oct. 1, 2017 - Courtesy of www.wpra.com two-time WPRA Reserve World Champion TR for the 2017 National Finals Rodeo. Be- 1 Tiany Schuster $250,377 93 Dashing Badger (“Dolly”)), entered in the BFA fore the ink was dry on the time sheets 2 Stevi Hillman $185,952 96 World Championship Futurity in Oklahoma at the rodeos in the West on Saturday 3 Nellie Miller $130,536 47 City. night, the field for the 2017 NFR was 4 Amberleigh Moore $120,806 50 On late Friday afternoon, Sherry Cervi, set. 5 Kassie Mowry $115,162 25 who at 16th in the standings had the best The defining moment came Friday 6 Kathy Grimes $111,785 45 chance of cracking the Top 15, took to Face- night when Kimmie Wall and her gritty 7 Hailey Kinsel $98,706 68 book to thank her supporters and commend her mare TKW Bullysfamous Fox picked 8 Taci Bettis (R) $97,023 70 fellow competitors. -

Chilli Dating Anyone in ? the 'Girls Cruise' Star Is Opening up About Heartbreak Navigation Menu

Jul 22, · Chilli's journey towards finding love in the public eye has been well-documented from a high-profile relationship with Usher to What Chilli Wants, her former reality show about her quest to Author: Tai Gooden. Aug 20, · Rozonda “Chilli” Thomas, 47, wants Black women to shake up their dating habits and explore what it’s like to go out with men outside of their race.. One-third of the iconic girl group TLC. Is Chilli Dating Anyone In ? The 'Girls Cruise' Star Is Opening Up About Heartbreak Navigation menu. In, Thomas and Watkins performed a series of concerts in Asia. In, Thomas lost her dating and was ordered by doctors right to sing. Thomas began working on her chilli album in after the completion of dating for TLC's third album, FanMail. Jan 30, · Chilli, meanwhile, hasn't exactly had it easy in her dating life. Back in , she had a very high- profile relationship with the R&B singer Usher, which ended when she realized that he was. Rozonda Ocielian Thomas born February 27,, dated professionally as Chilli, is an American singer-songwriter, tionne, actress, television personality and model who rose to fame in the early s as a dating of group TLC, one of the best-selling girl groups of the 20th dating. Rozonda 'Chilli' Thomas is dated to have hooked up with Wayne Brady in. Aug 20, · Rozonda "Chilli" Thomas has some advice for Black woman looking for that Prince Charming,. She wants them to date "primarily" White men. Chilli spoke with Essence to promote the eight-part Netflix music documentary series Once In A Lifetime Sessions which features TLC. -

Girl Scout Brownies

The Tobin Endowment Girl Scout Brownies Girl Scouts of Southwest Texas To learn more about The Tobin 811 North Coker Loop Endowment and their mission, San Antonio, Texas 78216 visit www.tobinendowment.org (210) 349- 2404 or 1-800-580-7247 www.girlscouts-swtx.org Girl Scouts of Southwest Texas & The Tobin Endowment are proud to bring to you the… The Tobin Endowment The Arts Initiative The arts inspire girls of all ages to explore visual expression and ideas in music, theatre and dance. The Tobin Endowment Arts Initiative incorporates education in visual and performing arts. Through arts programs, girls focus on self-expression and discovery. The arts are vital to youth development and provide limitless possibilities for growth and exploration. Research shows that arts can reach students where other academic subjects cannot. With arts-integrated learning, students gain a greater depth of understanding of academic topics. Girl Scouts who complete The Tobin Endowment Arts Initiative develop their artistic skills and learn about the performing arts through pathways which include painting, sculpture, jazz, blues, rap, classical music and dance. The Tobin Endowment Girl Scout Brownies 2 Steps to Earn the The Tobin Endowment the Arts Patch Girl Scouts is the premier girl leadership development program—girls have fun with a purpose! All activities are girl-led and girls should decide what activities to complete when earning a Business Patch Initiative (BPI) patch. In the spirit of Girl Scouting, girls may choose to participate in activities that are not listed in the booklets and/or supplements. If girls complete the minimum required number of activities based on the theme of the BPI, they have earned the BPI patch. -

World Dog Show Leipzig 2017

WORLD DOG SHOW LEIPZIG 2017 09.-12. November 2017, Tag 1 in der Leipziger Messe Schirmherrin: Staatsministerin für Soziales und Verbraucherschutz Barbara Klepsch Patron: Minister of State for Social Affairs and Consumer Protection Barbara Klepsch IMPRESSUM / FLAG Veranstalter / Promoter: Verband für das Deutsche Hundewesen (VDH) e.V. Westfalendamm 174, 44141 Dortmund Telefon: (02 31) 5 65 00-0 Mo – Do 9.00 – 12.30/13.00 – 16.00 Uhr, Fr 9.00 – 12.30 Uhr Telefax: (02 31) 59 24 40 E-Mail: [email protected], Internet: www.vdh.de Chairmann/ Prof. Dr. Peter Friedrich Präsident der World Dog Show Secretary / Leif Kopernik Ausstellungsleitung Organization Commitee / VDH Service GmbH, Westfalendamm 174, 44141 Dortmund Organisation USt.-IdNr. DE 814257237 Amtsgericht Dortmund HRB 18593 Geschäftsführer: Leif Kopernik, Jörg Bartscherer TAGESEINTEILUNG / DAILY SCHEDULE DONNERSTAG, 09.11.2017 / THURSDAY, 09.11.2017 FCI-Gruppen: 4, 6, 7, 8 Gruppe 4/ Group 4: Teckel / Dachshunds Gruppe 6 / Group 6: Lauf- und Schweisshunde / Scent hounds and related breeds Gruppe 7/ Group 7: Vorstehhunde (Kontinentale-, Britische- und Irische-) / Pointing Dogs Gruppe 8 / Group 8: Apportier-, Stöber- und Wasserhunde / Retrievers - Flushing Dogs - Water Dogs TAGESABLAUF / DAILY ROUTINE 7.00 – 9.00 Uhr Einlass der Hunde / Entry for the Dogs 9.00 – 15.15 Uhr Bewertung der Hunde / Evaluation of the Dogs NOTICE: The World Winner 2017, World Junior Winner 2017 and the World Veteran Winner will get a Trophy. A Redelivery is not possible. HINWEIS: Die World Winner 2017, World Junior Winner 2017 und der World Veteranen Winner 2017 erhal- ten einen Pokal. Eine Nachlieferung ist nach der Veranstaltung nicht möglich. -

BOOK of ABSTRACTS KEYNOTES Building Bridges for Physical Activity and Sport

Association Internationale des Ecoles Superieures d’Education Physique International Association for Physical Education in Higher Education International Conference Pre-Conference Events: June 16-19, 2019 Main Conference: June 19-22, 2019 BOOK OF ABSTRACTS KEYNOTES Building Bridges for Physical Activity and Sport Examining the Intersection of Social and Emotional Learning with Physical Education and Youth Sport Thursday, 20th June - 08:15: (Performing Arts Center Main Theater) Paul Wright ( Department of Kinesiology and Physical Education, Northern Illinois University ) Within physical education and youth sport communities, there is a surge of interest in social and emotional learning. While research, conceptual frameworks, and policy support related to the broad notion of social and emotional learning are compelling and have much to offer, we must remember many relevant concepts and practices have already been developed in physical education and youth sport programs. Don Hellison’s Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility model is one such example. This is not so say we have nothing to learn. In fact, we have much to learn AND much to share. This keynote presentation will examine the intersection of social and emotional learning with physical education and youth sport. Opportunities and challenges will be discussed that may inform best practices for designing and delivering programs, training teachers and coaches, as well as strengthening research and policy support in this area. Building Bridges for Physical Activity and Sport How do you create, engage, and amplify a health promotion program: the Hip Hop Public Health approach Thursday, 20th June - 15:30 PM: (Performing Arts Center Main Theater) Olajide Williams ( Columbia University, NY, USA and Hip Hop Public Health ) This talk will present Hip Hop Public Health’s evidence-driven Multisensory Multilevel Health Education Model, and it’s potential role in improving physical activity behaviors of children in low income urban communities of the United States. -

Sexuality in Toni Morrison's Works

SEXUALITY IN TONI MORRISON’S WORKS by Birgit Aas Holm Master’s Thesis in English Literature ENG-3992 Department of Culture and Literature Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education University of Tromsø Autumn Term 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my supervisor Professor Fredrik Chr. Brøgger at the University of Tromsø for his useful guidance, patience and insightful comments through my process of writing. It is due to his continuous support and encouragement that I have been able to complete this work. I would also like to extend my thanks to colleagues, friends and family for contributing with useful discussions. Finally, I wish to express my gratefulness to my husband and two daughters for their love and support, and for giving me the time to concentrate on this work. 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER 1. SOME THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES ............................................. 10 CHAPTER 2. SEXUALITY AND GENDER IN SULA .................................................... 17 CHAPTER 3. SEXUALITY AND OPPRESSION IN THE BLUEST EYE ..................... 38 CHAPTER 4. SEXUALITY AND LOVE IN LOVE .......................................................... 60 CONCLUSION....................................................................................................................... 90 BIBLIOGRAPHY …………………………………………………………………………. 94 2 INTRODUCTION Sexuality is of course linked to the very biology of human beings. Sexuality pervades people‟s lives, on all levels of society. There have, of course, been numerous studies of, and hence massive disagreements about, the biological aspect of sexuality and sexual preferences in humans, as well as of sexual deviance of different kinds. There are many studies that inquire into whether the many and diverse expressions of sexuality are the results of biology or of social construction, and the answers tend to reflect the viewpoints of the authors of such studies. -

Arrowverse Expands

AJW Landscaping • 910-271-3777 We’ll makeyour yard BOO-ti-ful! October 5 - 11, 2019 Ruby Rose as Kate Kane in “Batwoman” Arrowverse 12780 S Caledonia Rd expands Laurinburg, NC 28352 910-276-7474 Joy Jacobs, Store Manager 234 E. Church Street, Laurinburg NC 910-277-8588 www.kimbrells.com Page 2 — Saturday, October 5, 2019 — Laurinburg Exchange Holy diversity Batman!: ‘Batwoman’ premieres on CW By Breanna Henry I say that Batwoman, a.k.a. Kate With the beautifully androgynous pect from Batwoman and Alice’s TV Media Kane, is a fantastic character with a Ruby Rose (“The Meg,” 2018) at on-screen relationship. For those ton of incredible story potential. the helm (or cowl) and Rachel not familiar with Rucka’s work, just may or may not own an overflow- As someone who’s already a fan, Skarsten (“Acquainted,” 2018) know that you’re in for some of the Iing stack of comic books that’s I’m very interested to see how CW’s playing the totally twisted Alice, “Batwoman” comic books’ most getting dangerously close to weigh- “Batwoman” recreates, reimagines CW’s newest prime-time addition to outrageous, unexpected and dis- ing more than its current shelf can or reinvents the title character, and its DC Comics-based Arrowverse — turbing twists and turns. The psy- handle, so it’s safe to trust me when luckily I won’t have to wait long. “Batwoman” — premieres Sunday, chedelic imagery and mind-warping Oct. 6. colors for which the comic is known FOR NEW ACCOUNTS Not everyone seems to be as ex- don’t seem to have been carried cited as I am about CW’s “Batwom- over to the new TV series, but other an.” Many of the preemptively neg- such DC Comics television pro- UP ative thoughts are likely the result grams (“Arrow,” “The Flash,” “Su- SAVE of people being afraid.