Dancer to Dancer: First Encounters with Balanchine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

18Th Century Dance

18TH CENTURY DANCE THE 1700’S BEGAN THE ERA WHEN PROFESSIONAL DANCERS DEDICATED THEIR LIFE TO THEIR ART. THEY COMPETED WITH EACH OTHER FOR THE PUBLIC’S APPROVAL. COMING FROM THE LOWER AND MIDDLE CLASSES THEY WORKED HARD TO ESTABLISH POSITIONS FOR THEMSELVES IN SOCIETY. THINGS HAPPENING IN THE WORLD IN 1700’S A. FRENCH AND AMERICAN REVOLUTIONS ABOUT TO HAPPEN B. INDUSTRIALIZATION ON THE WAY C. LITERACY WAS INCREASING DANCERS STROVE FOR POPULARITY. JOURNALISTS PROMOTED RIVALRIES. CAMARGO VS. SALLE MARIE ANNE DE CUPIS DE CAMARGO 1710 TO 1770 SPANISH AND ITALIAN BALLERINA BORN IN BRUSSELS. SHE HAD EXCEPTIONAL SPEED AND WAS A BRILLIANT TECHNICIAN. SHE WAS THE FIRST TO EXECUTE ENTRECHAT QUATRE. NOTEWORTHY BECAUSE SHE SHORTENED HER SKIRT TO SEE HER EXCEPTIONAL FOOTWORK. THIS SHOCKED 18TH CENTURY STANDARDS. SHE POSSESSED A FINE MUSICAL SENSE. MARIE CAMARGO MARIE SALLE 1707-1756 SHE WAS BORN INTO SHOW BUSINESS. JOINED THE PARIS OPERA SALLE WAS INTERESTED IN DANCE EXPRESSING FEELINGS AND PORTRAYING SITUATIONS. SHE MOVED TO LONDON TO PUT HER THEORIES INTO PRACTICE. PYGMALION IS HER BEST KNOWN WORK 1734. A, CREATED HER OWN CHOREOGRAPHY B. PERFORMED AS A DRAMATIC DANCER C. DESIGNED DANCE COSTUMES THAT SUITED THE DANCE IDEA AND ALLOWED FREEDOM OF MOVEMENT MARIE SALLE JEAN-GEORGES NOVERRE 1727-1820; MOST FAMOUS PERSON OF 18TH CENTURY DANCE. IN 1760 WROTE LETTERS ON DANCING AND BALLETS, A SERIES OF ESSAYS ATTACKING CHOREOGRAPHY AND COSTUMING OF THE DANCE ESTABLISHMENT ESPECIALLY AT PARIS OPERA. HE EMPHASIZED THAT DANCE WAS AN ART FORM OF COMMUNICATION: OF SPEECH WITHOUT WORDS. HE PROVED HIS THEORIES BY CREATING SUCCESSFUL BALLETS AS BALLET MASTER AT THE COURT OF STUTTGART. -

The Mariinsky Ballet & Orchestra

Thursday, October 1, 2015, 8pm Friday, October 2, 2015, 8pm Saturday, October 3, 2015, 2pm & 8pm Sunday, October 4, 2015, 3pm Zellerbach Hall The Mariinsky Ballet & Orchestra Gavriel Heine, Conductor The Company Diana Vishneva, Nadezhda Batoeva, Anastasia Matvienko, Sofia Gumerova, Ekaterina Chebykina, Kristina Shapran, Elena Bazhenova Vladimir Shklyarov, Konstantin Zverev, Yury Smekalov, Filipp Stepin, Islom Baimuradov, Andrey Yakovlev, Soslan Kulaev, Dmitry Pukhachov Alexandra Somova, Ekaterina Ivannikova, Tamara Gimadieva, Sofia Ivanova-Soblikova, Irina Prokofieva, Anastasia Zaklinskaya, Yuliana Chereshkevich, Lubov Kozharskaya, Yulia Kobzar, Viktoria Brileva, Alisa Krasovskaya, Marina Teterina, Darina Zarubskaya, Olga Gromova, Margarita Frolova, Anna Tolmacheva, Anastasiya Sogrina, Yana Yaschenko, Maria Lebedeva, Alisa Petrenko, Elizaveta Antonova, Alisa Boyarko, Daria Ustyuzhanina, Alexandra Dementieva, Olga Belik, Anastasia Petushkova, Anastasia Mikheikina, Olga Minina, Ksenia Tagunova, Yana Tikhonova, Elena Androsova, Svetlana Ivanova, Ksenia Dubrovina, Ksenia Ostreikovskaya, Diana Smirnova, Renata Shakirova, Alisa Rusina, Ekaterina Krasyuk, Svetlana Russkikh, Irina Tolchilschikova Alexey Popov, Maxim Petrov, Roman Belyakov, Vasily Tkachenko, Andrey Soloviev, Konstantin Ivkin, Alexander Beloborodov, Viktor Litvinenko, Andrey Arseniev, Alexey Atamanov, Nail Enikeev, Vitaly Amelishko, Nikita Lyaschenko, Daniil Lopatin, Yaroslav Baibordin, Evgeny Konovalov, Dmitry Sharapov, Vadim Belyaev, Oleg Demchenko, Alexey Kuzmin, Anatoly Marchenko, -

Educational Packet the Roaring 20'S

Educational Packet *BE Sure to click on the links for detailed information and Videos* The RoaRing 20’s F. Scott Fitzgerald Zelda Fitzgerald flappers The Charleston Lindy hoppers The Lindy HOp BALLET TERMINOLOGY Adagio – A dance movement done in a slow tempo. Allegro – A dance movement done in a fast tempo. Arabesque – A ballet position in which one leg is raised straight behind the body while the dancer balances on the other leg. The position has many variations, with the leg sometimes low and sometimes high, or with the leg pointed almost straight up, as in Arabesque Penchee. Attitude – A ballet position in which one leg is raised either in front of (Attitude Avant) or behind (Attitude Derriere) the body, with the knee slightly bent. Ballerina – This is a title that is given to principal or “Star” female dancers in a ballet company. Ballet – From the Italian, “Ballare,” to dance. Ballet d’Action – A dance that tells a story. Barre – The wooden rail that is attached to the walls of a dance studio for dancers to hold onto during warm-up. The barre is used to help dancers find and practice balance. Batterie – A term referring to the fast and rhythmic beating of the legs, one against the other, to add excitement to a jump. Bourees – A series of many tiny steps on points that make the dancer seem to glide across the stage. Character Dance – Folk dances that have their roots in different countries of the world. Examples: Mazurka – Polish; Czardas-Hungarian; Bolero – Spanish; Gigue – French. The term “character dance” also refers to roles that are largely mimed or comic, such as the role of Dr. -

Call Number DVD-5801 BARNET, Boris Shchedroe Leto

09 January 2020 SSEES DVDs Nos 5801-5900 Page 1 Call number DVD-5801 BARNET, Boris Shchedroe leto [The Generous Summer] [Bountiful Summer] Kievskaia kinostudiia khudozhestvennykh fil´mov, 1950; released 8 March 1951 Screenplay: Evgenii Pomeshchikov, Nikolai Dalekii Photography: Aleksei Mishurin Production design: Oleg Stepanenko, N. Iurov Music: German Zhukovskii Song lyrics: A. Malyshko Nazar Protsenko Nikolai Kriuchkov Vera Goroshko Nina Arkhipova Petr Sereda Mikhail Kuznetsov Oksana Podpruzhenko Marina Bebutova Ruban Viktor Dobrovol´skii Tesliuk Konstantin Sorokin Darka Muza Krepkogorskaia Kolodochka Evgenii Maksimov Prokopchuk Anton Dunaiskii Podpruzhenko Mikhail Vysotskii Zoological technician Alla Kazanskaia Ekaterina Matveevna Vera Kuznetsova Musii Antonovich Georgii Gumilevskii Dar´ia Kirillovna, his wife Tat´iana Barysheva 82 minutes In Russian with optional English subtitles DVD Region code Aspect ratio Languages Optional English subtitles Features Chapter selection Source Rare Films and More 09 January 2020 SSEES DVDs Nos 5801-5900 Page 2 Call number DVD-5802 BASOV, Vladimir Pavlovich Shchit i mech [Shield and Sword] Fil´m 1. Bez prava byt´ soboi [Film 1. Without the Right to be Yourself] Mosfil´m, Tvorcheskoe ob´´edinenie pisatelei i kinorabotnikov, with Defa, East Germany and Start, Poland, 1967; released 19 August 1968 AND Fil´m 2. Prikazano vyzhit´ [Film 2. Ordered to Survive] Mosfil´m, Tvorcheskoe ob´´edinenie pisatelei i kinorabotnikov, with Defa, East Germany and Start, Poland, 1967; released 19 August 1968 AND Shchit i mech [Shield and Sword] Fil´m 3. Obzhalovaniiu ne podlezhit [Film 3. Without the Right of Appeal] Mosfil´m, Tvorcheskoe ob´´edinenie pisatelei i kinorabotnikov, with Defa, East Germany and Start, Poland, 1967; released 2 September 1968 AND Shchit i mech [Shield and Sword] Fil´m 4. -

Support Materials

720 352 2903 LEMON SPONGE CAKE CONTEMPORARY BALLET [email protected] 1. ABOUT THE ARTIST 720 352 2903 LEMON SPONGE CAKE CONTEMPORARY BALLET [email protected] ROBERT SHER-MACHHERNDL 720 771 0162 [email protected] www.lemonspongecake.org PROFILE Robert Sher-Machherndl, a native of Vienna, Austria, has enjoyed a distinguished career in the performing arts ranging from Principal Dancer, Choreographer, Master Teacher to Artistic Director. He is currently Artistic Director and Choreographer of Lemon Sponge Cake Contemporary Ballet, from 2000 to present. SELECT CHOREOGRAPHIES • 2020 Seriously Solo - Boulder JCC • 2019 Dexter - Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music & Dance, London, UK • 2019 Juliet - Boulder JCC • 2018 Gone - Junction Place, Boulder • 2017 Grasping Aspects of Shekhinah - University of Colorado Boulder • 2017 Vertical Migration Experiment - Boulder JCC • 2016 White Fields - Public Art Commission, City of Boulder • 2016 White Mirror Second Look - Ellie Caulkins Opera House, Denver • 2015 White Mirror - Bowdoin College, Maine • 2015 Rush - National College Dance Festival, Kennedy Center for Performing Arts • 2015 Rush - Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco • 2015 White Mirror - Public Art Commission, City of Denver • 2014 Solo - Ballet Next, Joyce Theater, New York City • 2014 Hanna - Vienna State Ballet /Jugendkompanie, Vienna State Opera, Austria • 2014. Leopoldstatdt 22 - Mizel Museum, Denver • 2013 Man Made Men - Dairy Art Center, Boulder • 2012 Scarlet - Dairy Art Center, Boulder • 2011 BluePrint - Newman -

Sadler's Wells & BBC Arts

Dancing Nation Running order Programme 1 Spitfire - an advertisement divertissement New Adventures, choreography by Matthew Bourne Face In (excerpt) Candoco Dance Company, choreography by Yasmeen Godder Window Shopping Curated by Breakin’ Convention Orbis (excerpt) HUMANHOOD, choreography by Júlia Robert and Rudi Cole Hollow English National Ballet, choreography by Stina Quagebeur Programme 2 Sphera (excerpt) HUMANHOOD, choreography by Júlia Robert and Rudi Cole BLKDOG (excerpt) Far From The Norm, choreography by Botis Seva Lazuli Sky (excerpt) Birmingham Royal Ballet, choreography by Will Tuckett Hope Hunt and the Ascension into Lazarus (excerpt) Choreography by Oona Doherty Whyte (excerpt) from Blak Whyte Gray Boy Blue, choreography by Kenrick ‘H2O’ Sandy and Michael ‘Mikey J’ Asante Mud of Sorrow: Touch Choreography by Akram Khan, with Natalia Osipova Programme 3 Shades of Blue (excerpt) Matsena Productions, choreography by Anthony Matsena and Kel Matsena States of Mind Northern Ballet, choreography by Kenneth Tindall Contagion (excerpt) Shobana Jeyasingh Dance, choreography by Shobana Jeyasingh Rouge (excerpt) Rambert, choreography by Marion Motin Left: Rambert, Rouge © Johan Persson Front cover: Rambert, Rouge © Johan Persson 2 PROGRAMME 1 Spitfire - an advertisement divertissement New Adventures Choreography: Matthew Bourne Before his legendary Swan Lake, Nutcracker! and Cinderella, Matthew Bourne created his first hit, Spitfire (1988). This hilarious work places the most famous nineteenth-century ballet showstopper ‘Pas De Quatre’ in the world of men’s underwear advertising. Both a celebration of male vanity and an affectionate comment on the preening grandeur of the danseur noble, Spitfire was last performed in 2012. The piece featured in a triple bill celebrating New Adventures’ 25th anniversary celebrations. -

Press Information → 2020/21 Season

Press Information → 2020/21 Season THE VIENNA ① STATE BALLET 2020/21 »Along with my team and my dancers, I intend to work towards developing the Vienna State Ballet into a major hotspot of the art of dance in Austria and Europe forming an ensemble that reflects and inspires the traditions, changes and innovations of the lively metropolis, city of art and music, Vienna.« Martin Schläpfer Martin Schläpfer takes over the direction of the Vienna State Ballet with the 2020 / 21 season. The renowned Swiss choreographer and ballet director has recently led the multi-award-winning Ballett am Rhein Düsseldorf Duisburg to international acclaim. His works fascinate with their intensity, their virtuosity, their deeply moving images and a concise language of movement, which is understood as making music with the body, but always reflects the atmosphere and questions of today’s world. Several performances offer the opportunity to encounter Martin Schläpfer’s art – including two world premieres: Two new pieces for Vienna are being created to Gustav Mahler’s 4th Symphony and Dmitri Shostakovich’s 15th Symphony, which also mark the beginning of the intensive creative dialogue that Martin Schläpfer will be establishing with the artists of his ensemble in the coming years. As director, Martin Schläpfer is a bridge-builder who will naturally continue to cultivate the great ballet traditions, but will also enrich the programme with important contemporary artists and a great variety of choreographic signatures. The masters of American neo-classical ballet George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins will continue to be among the fixed stars of the Vienna repertoire, as will the Dutchman Hans van Manen. -

DOCTORAL THESIS the Dancer's Contribution: Performing Plotless

DOCTORAL THESIS The Dancer's Contribution: Performing Plotless Choreography in the Leotard Ballets of George Balanchine and William Forsythe Tomic-Vajagic, Tamara Award date: 2013 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 THE DANCER’S CONTRIBUTION: PERFORMING PLOTLESS CHOREOGRAPHY IN THE LEOTARD BALLETS OF GEORGE BALANCHINE AND WILLIAM FORSYTHE BY TAMARA TOMIC-VAJAGIC A THESIS IS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF PHD DEPARTMENT OF DANCE UNIVERSITY OF ROEHAMPTON 2012 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the contributions of dancers in performances of selected roles in the ballet repertoires of George Balanchine and William Forsythe. The research focuses on “leotard ballets”, which are viewed as a distinct sub-genre of plotless dance. The investigation centres on four paradigmatic ballets: Balanchine’s The Four Temperaments (1951/1946) and Agon (1957); Forsythe’s Steptext (1985) and the second detail (1991). -

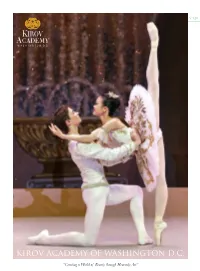

Kirov Academy of Washington D.C

V.1.01 W A S H I N G T O N, D. C. KIROV ACADEMY OF WASHINGTON D.C. “Creating a World of Beauty through Heavenly Art” 2 3 [ Our Vision ] CONTENTS The Kirov Academy is dedicated to artistic and academic excellence and to the investment of a moral education in our 2 Table of Contents students. Founded on universal principles of love, respect, 3 Our Vision and service, The Kirov Academy believes in the importance of the arts and culture in creating a world of beauty and 4 Founders effectuating positive change. 5 Advisory Board 6 History of Kirov Academy 8 Ballet Curriculum Our mission is to inspire students to excel by drawing on the exceptional traditions of the past, and by applying their own 12 Music Curriculum unique talents to become the best they can be. 16 Academy Curriculum 18 Student Life 20 Summer Program 22 Admissions 23 Scholarships 24 Awards 26 Alumni 4 5 [ Founders ] CREATING A WORLD OF BEAUTY THROUGH HEAVENLY ART Sergei Dorensky Sergei Dorensky is known as one of the most outstanding pianists and teachers of the former Soviet Union. Sergei Dorensky has been awarded numerous international prizes over the years and eventually went on to develop his career outside the Soviet Union. Sergei Dorensky was also named “People’s Artist of Russia” in 1989 and received the Order for Merit to the Fatherland in 2008. The vision of the Founders of the Academy, the late Rev. Dr. Sun Myung Moon and Dr. Hak Ja Gary Graffman Han Moon, can be understood in the calligraphy. -

Graeme Murphys Romeo and

DANA STEPHENSEN, CORYPHÉE 2011 SEASON MELBOURNE 13 – 24 September the Arts Centre, State Theatre with Orchestra Victoria SYDNEY 2 – 21 December Opera Theatre, Sydney Opera House with Australian Opera and Ballet Orchestra Mum’s lounge room Cavendish Road High School Davidia Lind Dance Centre The Australian Ballet The Arts Centre, Melbourne TELSTRA IS PROUD TO SUPPORT DANCERS AT EVERY STAGE It’s a long journey from those first hesitant steps to a performance on the world stage. Telstra proudly supports Australian dancers through community grants, the People’s Choice Award, and as principal partner of The Australian Ballet. Broadcast Sponsor Supporting Sponsor Supporting Sponsor Principal Sponsor Cover and above: Madeleine Eastoe and Kevin Jackson Photography Georges Antoni TCON1179_D Madeleine Eastoe Photography Georges Antoni NOTE FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR If you ask any dancer, they’ll say that Romeo This production will be such a valuable and Juliet is a ballet they aspire to dance. To addition to the repertoire and will give us a have the opportunity to have this classic tale new way to engage with this timeless story. created for you by one of the world’s great It is also a wonderful vehicle for the artistry narrative choreographers would be a dream of our talented dancers. Equally it has been come true. That is just what’s been happening an amazing showcase for the artisans who for the last few months! It has been so exciting make the sets, props and costumes, as to watch this new production take shape well as the technical staff who bring them across the company, in the rehearsal rooms, to the stage. -

Sydney Opera House

Together, we’re lifting Marcus higher. You voted Marcus Morelli as 2019 Telstra People’s Choice Winner. We’re proud to support his brilliant ballet talent through the Telstra Ballet Dancer Awards. Telstra and The Australian Ballet, celebrating 36 years of partnership. Marcus Morelli 2019 Telstra People’s Choice Winner Photographer: Justin Ridler 2 THE AUSTRALIAN BALLET 2020 SEASON Together, we’re lifting Marcus higher. You voted Marcus Morelli as 2019 Telstra People’s Choice Winner. We’re proud to support his brilliant ballet talent through the Telstra Ballet Dancer Awards. Telstra and The Australian Ballet, celebrating 36 years of partnership. 13 – 24 MARCH | Arts Centre Melbourne 3 – 22 APRIL | Sydney Opera House Government Commissioning Production Lead & Production Lead Principal Partners Partner Partner Partner Partner Partner Marcus Morelli 2019 Telstra People’s Choice Winner Imogen Chapman. Photography Justin Ridler Photographer: Justin Ridler Tzu-Chao Chou and Lana Jones in Dyad 1929 Photography Jim McFarlane 4 THE AUSTRALIAN BALLET 2020 SEASON NOTE FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR New works are the lifeblood of all arts companies. Over the centuries, dancers and dance makers have shaped and changed ballet, taking its technique to fresh and exciting places. In every generation a handful of visionaries can inspire us to see ballet through a new lens, and in turn inspire others to create. Volt is a celebration of this process. I first saw Wayne McGregor’s work in the early 2000s. The piece, brainstate, featured Deborah Bull, then a principal of The Royal Ballet, and it was riveting. Wayne went on to create works for the world’s most prestigious ballet companies. -

El Papel De La Mujer En La Historia Del Ballet

UNIVERSIDAD POLITÉCNICA DE VALENCIA Departamento de Comunicación Audiovisual, Documentación e Historia del Arte Coreógrafas, directoras y pedagogas: la contribución de la mujer al desarrollo del ballet y los cambios de paradigmas en la transición al s. XXI Programa de Doctorado en Música Tesis presentada por Ana Abad Carlés Dirigida por Dra. Inmaculada Álvarez Buenos Aires, agosto 2012 ÍNDICE ÍNDICE DE ILUSTRACIONES 5 ÍNDICE DE GRÁFICAS Y TABLAS 9 AGRADECIMIENTOS 11 RESUMEN (CASTELLANO) 13 RESUMEN (INGLÉS) 15 RESUMEN (VALENCIANO) 17 PREFACIO 19 INTRODUCCIÓN 25 La mujer en la danza como objeto de investigación 25 Hipótesis de la investigación 26 Delimitación geográfica, temporal y de género coreográfico 28 Metodología 33 Estado de la cuestión 39 Estructura de la tesis 49 El contexto español 55 PRIMERA PARTE: LA MUJER EN LA HISTORIA DEL BALLET 59 CAPÍTULO 1. EL CONCEPTO DE PIONERA Y LA MUJER EN EL BALLET EN EL S. XIX 61 1.1. Introducción 63 1.2. Marie Sallé (1707 - 1757) y el mito de la pionera 65 1.3. La bailarina como “receptora de pasos” 72 CAPÍTULO 2. LA NUEVA CONCEPCIÓN COREOGRÁFICA DEL S. XX 89 1 2.1. Introducción 91 2.2. Los Ballets Rusos de Diághilev 94 2.3. Bronislava Nijinska (1891 - 1972) 102 CAPÍTULO 3. LA MUJER EN EL BALLET EN EL S. XX 127 3.1. Introducción 129 3.2 El entorno británico 132 3.2.1 Ninette de Valois (1898 - 2001) 133 3.2.2 Marie Rambert (1888 - 1982) 142 3.2.3 Andrée Howard (1910 - 1968) 147 3.3. El entorno soviético 154 3.3.1.