The Travesty Dancer in Nineteenth-Century Ballet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

103 the Music Library of the Warsaw Theatre in The

A. ŻÓRAWSKA-WITKOWSKA, MUSIC LIBRARY OF THE WARSAW..., ARMUD6 47/1-2 (2016) 103-116 103 THE MUSIC LIBRARY OF THE WARSAW THEATRE IN THE YEARS 1788 AND 1797: AN EXPRESSION OF THE MIGRATION OF EUROPEAN REPERTOIRE ALINA ŻÓRAWSKA-WITKOWSKA UDK / UDC: 78.089.62”17”WARSAW University of Warsaw, Institute of Musicology, Izvorni znanstveni rad / Research Paper ul. Krakowskie Przedmieście 32, Primljeno / Received: 31. 8. 2016. 00-325 WARSAW, Poland Prihvaćeno / Accepted: 29. 9. 2016. Abstract In the Polish–Lithuanian Common- number of works is impressive: it included 245 wealth’s fi rst public theatre, operating in War- staged Italian, French, German, and Polish saw during the reign of Stanislaus Augustus operas and a further 61 operas listed in the cata- Poniatowski, numerous stage works were logues, as well as 106 documented ballets and perform ed in the years 1765-1767 and 1774-1794: another 47 catalogued ones. Amongst operas, Italian, French, German, and Polish operas as Italian ones were most popular with 102 docu- well ballets, while public concerts, organised at mented and 20 archived titles (totalling 122 the Warsaw theatre from the mid-1770s, featured works), followed by Polish (including transla- dozens of instrumental works including sym- tions of foreign works) with 58 and 1 titles phonies, overtures, concertos, variations as well respectively; French with 44 and 34 (totalling 78 as vocal-instrumental works - oratorios, opera compositions), and German operas with 41 and arias and ensembles, cantatas, and so forth. The 6 works, respectively. author analyses the manuscript catalogues of those scores (sheet music did not survive) held Keywords: music library, Warsaw, 18th at the Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych in War- century, Stanislaus Augustus Poniatowski, saw (Pl-Wagad), in the Archive of Prince Joseph musical repertoire, musical theatre, music mi- Poniatowski and Maria Teresa Tyszkiewicz- gration Poniatowska. -

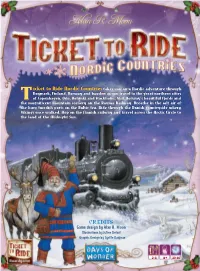

Rules EN 2015 TTR2 Rules Nordic EN 18/05/15 15:51 Page2

[T2RNordic] rules EN 2015_TTR2 rules Nordic EN 18/05/15 15:51 Page2 icket to Ride Nordic Countries takes you on a Nordic adventure through Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden as you travel to the great northern cities T of Copenhagen, Oslo, Helsinki and Stockholm. Visit Norway's beautiful fjords and the magnificent mountain scenery on the Rauma Railway. Breathe in the salt air of the busy Swedish ports on the Baltic Sea. Ride through the Danish countryside where Vikings once walked. Hop-on the Finnish railway and travel across the Arctic Circle to the land of the Midnight Sun. CREDITS Game design by Alan R. Moon Illustrations by Julien Delval Graphic Design by Cyrille Daujean 2-3 8+ 30-60’ [T2RNordic] rules EN 2015_TTR2 rules Nordic EN 18/05/15 15:52 Page3 Components 1 Globetrotter Bonus card u 1 Board map of Scandinavian train routes for the most completed tickets u 120 Colored Train cars (40 each in 3 different colors, plus a few spare) 46 Destination u 157 Illustrated cards: Ticket cards 110 Train cards : 12 of each color, plus 14 Locomotives ∫ ∂ u 3 Wooden Scoring Markers (1 for each player matching the train colors) u 1 Rules booklet Setting up the Game Place the board map in the center of the table. Each player takes a set of 40 Colored Train Cars along with its matching Scoring Marker. Each player places his Scoring Marker on the starting π location next to the 100 number ∂ on the Scoring Track running along the map's border. Throughout the game, each time a player scores points, he will advance his marker accordingly. -

Der Rosenkavalier by Richard Strauss

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2010 Octavian and the Composer: Principal Male Roles in Opera Composed for the Female Voice by Richard Strauss Melissa Lynn Garvey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC OCTAVIAN AND THE COMPOSER: PRINCIPAL MALE ROLES IN OPERA COMPOSED FOR THE FEMALE VOICE BY RICHARD STRAUSS By MELISSA LYNN GARVEY A Treatise submitted to the Department of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2010 The members of the committee approve the treatise of Melissa Lynn Garvey defended on April 5, 2010. __________________________________ Douglas Fisher Professor Directing Treatise __________________________________ Seth Beckman University Representative __________________________________ Matthew Lata Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I’d like to dedicate this treatise to my parents, grandparents, aunt, and siblings, whose unconditional love and support has made me the person I am today. Through every attended recital and performance, and affording me every conceivable opportunity, they have encouraged and motivated me to achieve great things. It is because of them that I have reached this level of educational achievement. Thank you. I am honored to thank my phenomenal husband for always believing in me. You gave me the strength and courage to believe in myself. You are everything I could ever ask for and more. Thank you for helping to make this a reality. -

Cesare Pugni: Esmeralda and Le Violon Du Diable

Cesare Pugni: Esmeralda and Le Violon du diable Cesare Pugni: Esmeralda and Le Violon du diable Edited and Introduced by Robert Ignatius Letellier Cesare Pugni: Esmeralda and Le Violon du diable, Edited by Edited and Introducted by Robert Ignatius Letellier This book first published 2012 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2012 by Edited and Introducted by Robert Ignatius Letellier and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-3608-7, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-3608-1 Cesare Pugni in London (c. 1845) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................... ix Esmeralda Italian Version La corte del miracoli (Introduzione) .......................................................................................... 2 Allegro giusto............................................................................................................................. 5 Sposalizio di Esmeralda ............................................................................................................. 6 Allegro giusto............................................................................................................................ -

Performing History Studies in Theatre History & Culture Edited by Thomas Postlewait Performing HISTORY

Performing history studies in theatre history & culture Edited by Thomas Postlewait Performing HISTORY theatrical representations of the past in contemporary theatre Freddie Rokem University of Iowa Press Iowa City University of Iowa Press, Library of Congress Iowa City 52242 Cataloging-in-Publication Data Copyright © 2000 by the Rokem, Freddie, 1945– University of Iowa Press Performing history: theatrical All rights reserved representations of the past in Printed in the contemporary theatre / by Freddie United States of America Rokem. Design by Richard Hendel p. cm.—(Studies in theatre http://www.uiowa.edu/~uipress history and culture) No part of this book may be repro- Includes bibliographical references duced or used in any form or by any and index. means, without permission in writing isbn 0-87745-737-5 (cloth) from the publisher. All reasonable steps 1. Historical drama—20th have been taken to contact copyright century—History and criticism. holders of material used in this book. 2. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945), The publisher would be pleased to make in literature. 3. France—His- suitable arrangements with any whom tory—Revolution, 1789–1799— it has not been possible to reach. Literature and the revolution. I. Title. II. Series. The publication of this book was generously supported by the pn1879.h65r65 2000 University of Iowa Foundation. 809.2Ј9358—dc21 00-039248 Printed on acid-free paper 00 01 02 03 04 c 54321 for naama & ariel, and in memory of amitai contents Preface, ix Introduction, 1 1 Refractions of the Shoah on Israeli Stages: -

NEW Media Document.Indd

MEDIA RELEASE WICKED is coming to Australia. The hottest musical in the world will open in Melbourne’s Regent Theatre in July 2008. With combined box office sales of $US 1/2 billion, WICKED is already one of the most successful shows in theatre history. WICKED opened on Broadway in October 2003. Since then over two and a half million people have seen WICKED in New York and just over another two million have seen the North American touring production. The smash-hit musical with music and lyrics by Stephen Schwartz (Godspell, Pippin, Academy Award-winner for Pocahontas and The Prince of Egypt) and book by Winnie Holzman (My So Called Life, Once And Again and thirtysomething) is based on the best-selling novel by Gregory Maguire. WICKED is produced by Marc Platt, Universal Pictures, The Araca Group, Jon B. Platt and David Stone. ‘We’re delighted that Melbourne is now set to follow WICKED productions in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, the North American tour and London’s West End,’ Marc Platt and David Stone said in a joint statement from New York. ‘Melbourne will join new productions springing up around the world over the next 16 months, and we’re absolutely sure that Aussies – and international visitors to Melbourne – will be just as enchanted by WICKED as the audiences are in America and England.’ WICKED will premiere in Tokyo in June; Stuttgart in November; Melbourne in July 2008; and Amsterdam in 2008. Winner of 15 major awards including the Grammy Award and three Tony Awards, WICKED is the untold story of the witches of Oz. -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

18Th Century Dance

18TH CENTURY DANCE THE 1700’S BEGAN THE ERA WHEN PROFESSIONAL DANCERS DEDICATED THEIR LIFE TO THEIR ART. THEY COMPETED WITH EACH OTHER FOR THE PUBLIC’S APPROVAL. COMING FROM THE LOWER AND MIDDLE CLASSES THEY WORKED HARD TO ESTABLISH POSITIONS FOR THEMSELVES IN SOCIETY. THINGS HAPPENING IN THE WORLD IN 1700’S A. FRENCH AND AMERICAN REVOLUTIONS ABOUT TO HAPPEN B. INDUSTRIALIZATION ON THE WAY C. LITERACY WAS INCREASING DANCERS STROVE FOR POPULARITY. JOURNALISTS PROMOTED RIVALRIES. CAMARGO VS. SALLE MARIE ANNE DE CUPIS DE CAMARGO 1710 TO 1770 SPANISH AND ITALIAN BALLERINA BORN IN BRUSSELS. SHE HAD EXCEPTIONAL SPEED AND WAS A BRILLIANT TECHNICIAN. SHE WAS THE FIRST TO EXECUTE ENTRECHAT QUATRE. NOTEWORTHY BECAUSE SHE SHORTENED HER SKIRT TO SEE HER EXCEPTIONAL FOOTWORK. THIS SHOCKED 18TH CENTURY STANDARDS. SHE POSSESSED A FINE MUSICAL SENSE. MARIE CAMARGO MARIE SALLE 1707-1756 SHE WAS BORN INTO SHOW BUSINESS. JOINED THE PARIS OPERA SALLE WAS INTERESTED IN DANCE EXPRESSING FEELINGS AND PORTRAYING SITUATIONS. SHE MOVED TO LONDON TO PUT HER THEORIES INTO PRACTICE. PYGMALION IS HER BEST KNOWN WORK 1734. A, CREATED HER OWN CHOREOGRAPHY B. PERFORMED AS A DRAMATIC DANCER C. DESIGNED DANCE COSTUMES THAT SUITED THE DANCE IDEA AND ALLOWED FREEDOM OF MOVEMENT MARIE SALLE JEAN-GEORGES NOVERRE 1727-1820; MOST FAMOUS PERSON OF 18TH CENTURY DANCE. IN 1760 WROTE LETTERS ON DANCING AND BALLETS, A SERIES OF ESSAYS ATTACKING CHOREOGRAPHY AND COSTUMING OF THE DANCE ESTABLISHMENT ESPECIALLY AT PARIS OPERA. HE EMPHASIZED THAT DANCE WAS AN ART FORM OF COMMUNICATION: OF SPEECH WITHOUT WORDS. HE PROVED HIS THEORIES BY CREATING SUCCESSFUL BALLETS AS BALLET MASTER AT THE COURT OF STUTTGART. -

Download Download

ISSN 2002-3898 © Ken Nielsen and Nordic Theatre Studies DOI: https://doi.org/10.7146/nts.v25i1.110898 Published with support from Nordic Board for Periodicals in the Humanities and Social Sciences (NOP-HS) Gone With the Plague: Negotiating Sexual Citizenship in Crisis Ken Nielsen ABSTRACT This article suggests that two historical performances by the Danish subcultural theatre group Buddha og Bag- bordsindianerne should be understood not simply as underground, amateur cabarets, but rather that they should be theorized as creating a critical temporality, as theorized by David Román. As such, they function to complicate the past and the present in rejecting a discourse of decency and embracing a queerer, more radical sense of citizenship. In other words, conceptualizing these performances as critical temporalities allows us not only to understand two particular theatrical performances of gay male identity and AIDS in Copenhagen in the late 1980s, but also to theorize more deeply embedded tensions between queer identities, temporality, and citizenship. Furthermore, by reading these performances and other performances like them as critical temporalities we reject the willful blindness of traditional theatre histories and make a more radical theatre history possible. Keywords: BIOGRAPHY Ken Nielsen is a Postdoctoral lecturer in the Princeton Writing Program, Princeton University, where he is currently teaching classes ranging from contemporary confession culture to tragedy. He holds a PhD in the- atre studies from The Graduate Center, City University of New York, with an emphasis on Gay and Lesbian Studies from the Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies (CLAGS). In addition, he holds an MA in Theatre Research from the University of Copenhagen. -

Romantic Ballet

ROMANTIC BALLET FANNY ELLSLER, 1810 - 1884 SHE ARRIVED ON SCENE IN 1834, VIENNESE BY BIRTH, AND WAS A PASSIONATE DANCER. A RIVALRY BETWEEN TAGLIONI AND HER ENSUED. THE DIRECTOR OF THE PARIS OPERA DELIBERATELY INTRODUCED AND PROMOTED ELLSLER TO COMPETE WITH TAGLIONI. IT WAS GOOD BUSINESS TO PROMOTE RIVALRY. CLAQUES, OR PAID GROUPS WHO APPLAUDED FOR A PARTICULAR PERFORMER, CAME INTO VOGUE. ELLSLER’S MOST FAMOUS DANCE - LA CACHUCHA - A SPANISH CHARACTER NUMBER. IT BECAME AN OVERNIGHT CRAZE. FANNY ELLSLER TAGLIONI VS ELLSLER THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN TALGIONI AND ELLSLER: A. TAGLIONI REPRESENTED SPIRITUALITY 1. NOT MUCH ACTING ABILITY B. ELLSLER EXPRESSED PHYSICAL PASSION 1. CONSIDERABLE ACTING ABILITY THE RIVALRY BETWEEN THE TWO DID NOT CONFINE ITSELF TO WORDS. THERE WAS ACTUAL PHYSICAL VIOLENCE IN THE AUDIENCE! GISELLE THE BALLET, GISELLE, PREMIERED AT THE PARIS OPERA IN JUNE 1841 WITH CARLOTTA GRISI AND LUCIEN PETIPA. GISELLE IS A ROMANTIC CLASSIC. GISELLE WAS DEVELOPED THROUGH THE PROCESS OF COLLABORATION. GISELLE HAS REMAINED IN THE REPERTORY OF COMPANIES ALL OVER THE WORLD SINCE ITS PREMIERE WHILE LA SYLPHIDE FADED AWAY AFTER A FEW YEARS. ONE OF THE MOST POPULAR BALLETS EVER CREATED, GISELLE STICKS CLOSE TO ITS PREMIER IN MUSIC AND CHOREOGRAPHIC OUTLINE. IT DEMANDS THE HIGHEST LEVEL OF TECHNICAL SKILL FROM THE BALLERINA. GISELLE COLLABORATORS THEOPHILE GAUTIER 1811-1872 A POET AND JOURNALIST HAD A DOUBLE INSPIRATION - A BOOK BY HEINRICH HEINE ABOUT GERMAN LITERATURE AND FOLK LEGENDS AND A POEM BY VICTOR HUGO-AND PLANNED A BALLET. VERNOY DE SAINTS-GEORGES, A THEATRICAL WRITER, WROTE THE SCENARIO. ADOLPH ADAM - COMPOSER. THE SCORE CONTAINS MELODIC THEMES OR LEITMOTIFS WHICH ADVANCE THE STORY AND ARE SUITABLE TO THE CHARACTERS. -

The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes In

THE USE OF THE POLISH FOLK MUSIC ELEMENTS AND THE FANTASY ELEMENTS IN THE POLISH FANTASY ON ORIGINAL THEMES IN G-SHARP MINOR FOR PIANO AND ORCHESTRA OPUS 19 BY IGNACY JAN PADEREWSKI Yun Jung Choi, B.A., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Adam Wodnicki, Major Professor Jeffrey Snider, Minor Professor Joseph Banowetz, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Choi, Yun Jung, The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes in G-sharp Minor for Piano and Orchestra, Opus 19 by Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2007, 105 pp., 5 tables, 65 examples, references, 97 titles. The primary purpose of this study is to address performance issues in the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, by examining characteristics of Polish folk dances and how they are incorporated in this unique work by Paderewski. The study includes a comprehensive history of the fantasy in order to understand how Paderewski used various codified generic aspects of the solo piano fantasy, as well as those of the one-movement concerto introduced by nineteenth-century composers such as Weber and Liszt. Given that the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, as well as most of Paderewski’s compositions, have been performed more frequently in the last twenty years, an analysis of the combination of the three characteristic aspects of the Polish Fantasy, Op.19 - Polish folk music, the generic rhetoric of a fantasy and the one- movement concerto - would aid scholars and performers alike in better understanding the composition’s engagement with various traditions and how best to make decisions about those traditions when approaching the work in a concert setting.