Purchasepro.Com, Inc. Securities Litigation 01-CV-0483-Second

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DISH 123 Pitchbook

DISH 123 Pitchbook ©2020 DISH Network L.L.C. All Rights Reserved English Programming What Are Your Must-Have Channels? All Packages Include Local Channels America’s Top 120 Our most popular package comes with 190 channels essential for any family, including USA, CMT, Disney Channel, E!, and ESPN. SAP SAP A&E HD Disney Channel (E) HD FXX HD National Geographic HD TNT HD AMC HD E! Entertainment Television HD getTV NBCSN HD truTV HD Animal Planet1 ESPN HD HGTV HD Newsmax Travel Channel HD HD 1 BabyFirstTV SAP ESPN2 HD History HD Newsy TVG SAP Bravo HD ESPNEWS HD HLN HD Nickelodeon/Nick at Nite (E) HD TVG2 C-SPAN SAP ESPNU HD HSN Paramount Network HD TV Land SAP C-SPAN2 FM IFC HD Pop HD USA HD 1 SAP SAP Cartoon Network Folk TV Investigation Discovery HD QVC HD VH1 HD HD 1 1 CNN HD SAP Food Network HD ION Recipe.TV WE tv HD SAP 1 CMT HD FOX Business Network HD Lifetime HD RIDE TV HD Weather Channel HD CNBC FOX News Channel HD MeTV SiriusXM–over 70 music channels WeatherNation HD HD 1 Comedy Central HD FOX Sports 1 HD MotorTrend HD only Syfy HD Z Living 1 SAP Discovery Channel HD Freeform HD MSNBC HD TBS HD Plus Many More DishHOME Interactive TV SAP Fuse HD MTV HD The Cowboy Channel HD SAP 1 DISH Studio HD FX HD MTV2 TLC HD America’s Top 120 Plus Includes all of America’s Top 120, plus even more sports. Includes all America’s Top 120 channels plus channels listed below. -

Download Symposium Brochure Incl. Programme

DEUTSCHE TV-PLATTFORM: HYBRID TV - BETTER TV HBBTV AND MUCH, MUCH MORE Deutsche TV Platform (DTVP) was founded more than 25 years ago to introduce and develop digital media tech- nologies based on open standards. Consequently, DTVP was also involved in the introduction of HbbTV. When the HbbTV initiative started at the end of 2008, three of the four participating companies were members of the DTVP: IRT, Philips, SES Astra. Since then, HbbTV has played an important role in the work of DTVP. For example, DTVP did achieve the activation of HbbTV by default on TV sets in Germany; currently, HbbTV 2.0 is the subject of a ded- icated DTVP task force within the Working Group Smart Media. HbbTV is a perfect blueprint for the way DTVP works by promoting the exchange of information and opinions between market participants, stakeholders and social groups, coordinating their various interests. In addition, DTVP informs the public about technological develop- ments and the introduction of new standards. In order to HYBRID BROADCAST BROADBAND TV (OR “HbbTV”) IS A GLOBAL INITIATIVE AIMED achieve these goals, the German TV Platform sets up ded- AT HARMONIZING THE BROADCAST AND BROADBAND DELIVERY OF ENTERTAIN- icated Working Groups (currently: WG Mobile Media, WG Smart Media, WG Ultra HD). In addition to classic media MENT SERVICES TO CONSUMERS THROUGH CONNECTED TVs, SET-TOP BOXES AND technology, DTVP is increasingly focusing on the conver- MULTISCREEN DEVICES. gence of consumer electronics, information technology as well as mobile communication. HbbTV specifications are developed by industry leaders opportunities and enhancements for participants of the To date, DTVP is the only institution for media topics in to improve the video user experience for consumers by content distribution value chain – from content owner to Germany with such a broad interdisciplinary membership enabling innovative, interactive services over broadcast consumer. -

Pay-TV Programmers & Channel Distributors

#GreatJobs C NTENT page 5 www.contentasia.tv l www.contentasiasummit.com Asia-Pacific sports Game over: StarHub replaces Discovery rights up 22% to 7 new channels standby for July rollout in Singapore US$5b in 2018 Digital rights driving inflation, value peaks everywhere except India Demand for digital rights will push the value of sports rights in the Asia-Pacific region (excluding China) up 22% this year to a record US$5 billion, Media Partners Asia (MPA) says in its new re- port, Asia Pacific Sports In The Age of GoneGone Streaming. “While sports remains the last bastion for pay-TV operators com- bating subscriber churn, OTT delivery is becoming the main driver of rights infla- tion, opening up fresh opportunities for rights-holders while adding new layers of complexity to negotiations and deals,” the report says. The full story is on page 7 Screen grab of Discovery’s dedicated campaign site, keepdiscovery.sg CJ E&M ramps up While Singapore crowds spent the week- StarHub is extending bill rebates to edu- Turkish film biz end staring at a giant #keepdiscovery cation and lifestyle customers and is also Korean remakes follow video display on Orchard Road, StarHub offering a free preview of 30 channel to 25 local titles was putting the finishing touches to its 15 July. brand new seven-channel pack includ- StarHub’s decision not to cave to Dis- ing, perhaps ironically, the three-year-old covery’s rumoured US$11-million demands Korea’s CJ E&M is ramping up its Turkish CuriosityStream HD channel launched by raised questions over what rival platform operations, adding 25 local titles to its Discovery founder John Hendricks. -

Channel-Guide-27-May-2018.Pdf

FIND ALL OF YOUR FAVOURITE CHANNEL GUIDE CHANNELS DIGITAL +2 DIGITAL +2 DIGITAL +2 § 111 funny .....................................111 154 Discovery Turbo .............. 634/620* 635/640* MTV Dance .............................. 804 13th STREET ........................118/117* 160 Disney Channel ......................... 707 MTV Music ............................... 803 On channels 831-860, you can access 30 ad-free A&E ........................................... 122 614/611* Disney Junior ............................ 709 MUTV ........................................ 518 audio channels playing your favourite music, Disney Movies ................. 404/400* 415/401* Action Movies ................. 406/409* 412/411* National Geographic ......... 610/613* 641 news and current affairs with no interruptions. Adults Only ............................ 960-1 Disney XD ................................. 708 foxtel tunes is part of your ENTERTAINMENT pack˚ Nat Geo WILD .................. 616/622* Al Jazeera English..................... 651 E! .............................................. 125 MAX 70s Hits Animal Planet ................... 615/621* ESPN ........................................ 508 NHK World ............................... 656 MAX 80s Hits Antenna .................................... 941 ESPN2 ...................................... 509 Nickelodeon ............................. 701 MAX 90s Hits Arena .................................105/112* 151 Eurosport ................................... 511 Nick Jr. ..................................... -

Bein Expands Its Portfolio with the Launch of Dkids Hd Dlife Hd And

BEIN EXPANDS ITS PORTFOLIO WITH THE LAUNCH OF DKIDS HD, DLIFE HD AND DMAX HD New Channels to launch this August, exclusively on beIN, offering content for the entire family This August beIN network will further extend its local presence with the launch of three new channels exclusive to beIN platform. Started from Monday 1 August, DKids HD, DLife HD and DMAX HD will add to beIN portfolio, showcasing an entertaining mixture of children’s, lifestyle and fact-based programming, thoughtfully curated for the entire family and all presented in stunning HD. Earlier this year, beIN network signed a new long-term partnership with Discovery to broaden its reach across the region with the launch six new channels in 2016. DKids HD, DLife HD and DMAX HD complete this current channel line-up, following the launch of Fatafeat HD, DTX HD and Animal Planet HD in April. Commenting on the addition of these new channels, Amanda Turnbull, VP and Country Manager, Discovery Networks MENA, said; "Discovery has been satisfying viewers’ curiosity for more than 30 years, building powerful, world-class brands along the way. We have leveraged this know-how to deliver three brand new channels for the Middle East, tailored specifically to meet the needs of local audiences, and complement and enhance beIN’s current offering. DKids, DLife and DMAX are channels the whole household can enjoy, with safe, fun, inspirational and educational programming designed to encourage viewers to get more from life. We are thrilled to present all three channels to beIN subscribers and look forward to building greater reach and following in the region.” Yousef Al Obaidly, Deputy CEO beIN Media Group was very confident that these three Discovery channels will further enhance beIN’s entertainment portfolio. -

MOBITV, INC., Et Al., Debtors.1 Chapter 11 Case No. 21

Case 21-10457-LSS Doc 292 Filed 05/21/21 Page 1 of 37 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE Chapter 11 In re: Case No. 21-10457 (LSS) MOBITV, INC., et al., Jointly Administe red 1 Debtors. Related Docket Nos. 73 and 164 ORDER (A) APPROVING THE SALE OF SUBSTANTIALLY ALL OF THE DEBTORS’ ASSETS FREE AND CLEAR OF ALL LIENS, CLAIMS, INTERESTS, AND ENCUMBRANCES AND (B) APPROVING THE ASSUMPTION AND ASSIGNMENT OF EXECUTORY CONTRACTS AND UNEXPIRED LEASES Upon the motion [Docket No. 73] (the “Sale Motion”)2 of the above-captioned debtors and debtors in possession (together, the “Debtors”) in these chapter 11 cases (the “Chapter 11 Cases”) for entry of an order (the “Sale Order”) (a) authorizing the sale of substantially all of the Debtors’ assets free and clear of all liens, claims, interests, and other encumbrances, other than assumed liabilities, to the party submitting the highest or otherwise best bid, (b) authorizing the assumption and assignment of certain executory contracts and unexpired leases, and (c) granting certain related relief, all as more fully described in the Sale Motion; and the Court having entered an order [Docket No. 164] (the “Bidding Procedures Order”) approving the Bidding Procedures; and the Debtors having conducted an Auction on May 11-12, 2021 pursuant to the Bidding Procedures and Bidding Procedures Order; and the Debtors having determined that the bid submitted by TiVo Corporation, 1 The Debtors in these chapter 11 cases and the last four digits of each Debtor’s U.S. tax identification number are as follows: MobiTV, Inc. -

Bein MEDIA GROUP Acquires the Largest Turkish Pay-TV Platform Digiturk

Page 1 of 2 beIN MEDIA GROUP acquires the largest Turkish Pay-TV platform Digiturk Acquisition of Digiturk marks the launch of in-country operations and the continued rapid expansion of beIN’s global footprint DOHA, ISTANBUL, JULY [10], 2015 – beIN MEDIA GROUP LLC (“beIN MEDIA”) is today pleased to announce it has signed a definitive agreement to acquire DP Acquisitions B.V., the holding company of the Turkish pay-TV group operating under the name Digiturk. beIN Group made acquired the shares from Çukurova Group and funds controlled by Providence Equity Partners. Management rights in respect of Çukurova Group’s ownership interest in Digiturk have been exercised by Turkey’s Savings Deposit Insurance Fund (TMSF) since May 2013. Digiturk is the leading pay-TV operator in Turkey with approximately 3.5 million subscribers, offering a premium mix of leading sports and entertainment content across 239 standard and high definition channels. In addition to all main Turkish channels in high definition, key content on offer to subscribers includes: . Sports: SporToto Süper Lig, Barclays Premier League, Russian and Brazilian League Football, Copa Del Rey, Turkish Airlines Euroleague Basketball, Beko Basketbol Ligi, Wimbledon and ATP Masters 1000 tennis, Formula 1 and a whole variety of top-class sports content . Entertainment: Showcasing movie and series offerings from the leading studios across the world including Disney, Paramount, 20th Century Fox, Warner Brothers, Universal, HBO and Lionsgate. Digiturk also carries a broad spectrum of channels to suit the diverse viewing demographics of the Turkish marketplace, including the Discovery Channel, Nickelodeon, E! Entertainment, MTV, CNBC, Animal Planet, National Geographic, and CNN Commenting on the transaction, Nasser Al-Khelaïfi, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of beIN MEDIA, said: “The acquisition of Digiturk is a key milestone in our vision of global expansion and our commitment to provide the highest quality broadcast experience in high growth potential and mature markets. -

Bein MEDIA GROUP Announces Satellite Migration to Eutelsat

General Business Use beIN MEDIA GROUP Announces Satellite Migration to Eutelsat Doha, Qatar – 17 December 2018: beIN MEDIA GROUP, the home of sports and entertainment in the MENA region has announced that it is migrating its transponder capacity from Nilesat over to Eutelsat 8 degrees West. This move comes as part of beIN’s commitment to providing its viewers and fans with the best possible technology and uninterrupted coverage in satellite TV broadcasting. Starting from the 15th of December until the 31st of December, beIN subscribers can watch content on all the available frequencies. After the 31st of December, subscribers will need to ensure their set top boxes are reconfigured to avoid any interruptions. beIN SPORTS channels HD1, HD2, HD3, HD4, HD2 MAX and HD3 MAX will now be available on Frequency MHz 11013. beIN SPORTS channels HD, HD5, HD6, HD7, HD8 and HD9 will be available on Frequency MHz 11054. beIN SPORTS channels beIN News, HD10, HD1 MAX and HD4 MAX will be available on Frequency MHz 12604. The switch of satellites provides an increase in platform security and control, and improved resilience overall. These efforts were made to ensure beIN MEDIA GROUP can continue to provide its viewers and fans with its unrivalled library of entertainment, live sport action and major international events in the highest standards available across all its platforms. The majority of set top boxes will be reconfigured automatically. For more information on beIN’s frequency change, please contact our call centre on: +97444222000 or visit: www.bein.net/serviceupdate. #END# General Business Use ABOUT beIN MEDIA GROUP beIN MEDIA GROUP, chaired by Nasser Al-Khelaifi, is an independent company established in 2014 with a vision to become a leading global sport and entertainment network. -

Contents Most Frequently Asked Questions

Contents Most Frequently Asked Questions ......................................................................... 3 Account and billing management ....................................................................... 3 1. About CAST ID .......................................................................................... 3 2. I have forgotten my CAST ID. How do I retrieve it? ................................... 4 3. I have forgotten my Singtel TV number. How do I retrieve it? .................... 4 4. I have forgotten my Singnet ID. How do I retrieve it? ................................. 5 5. Update/Reset CAST ID .............................................................................. 5 6. Update CAST Password ............................................................................ 6 7. How do I update my mobile number linked to my CAST account? ............ 6 Login troubleshooting .......................................................................................... 7 1. I am unable to login despite multiple tries. ................................................. 7 2. I am still not receiving any OTP despite multiple tries. How do I log in? .... 7 3. My Singtel 4G mobile data network is down. How do I log in? ................... 7 4. Why am I receiving these error messages? ............................................... 7 Video Playback troubleshooting ......................................................................... 8 1. I am currently receiving these video playback errors. What happened? .... 8 2. I am -

Fox Sports Foxtel Guide

Fox Sports Foxtel Guide Ricardo is foziest and kidnapped commercially while unobjectionable Raynard sjambok and deploring. Unreal and Bermudan Howie never preceded wherefore when Jerrome find-fault his dissertation. Unretentive and through Garfield fly mortally and wambled his runaways incommensurably and proverbially. Fox news reporting on fox sports foxtel guide to foxtel package also means that can use your channels will become one. The tv channels for free with several options, sports fox news series you agree with filipinos in the most viewed as. Allstreamingsites is fox sports guide channel guides to any just fine tuning into sport required for you can. Channel packs include kids, docos, sports and variety programming. Find out review's on Fox Sports 1 tonight at top American TV Listings Guide. Follow each guide note as for explain procedure to watch Super Bowl 2021 and. From the volume with root for the creation of your schedule, if you are a sponsored product. TV Guide FOX SPORTS. Go does that time for programming all of choices. 7 sports streaming services in Australia Live and inflate demand. Optimum is an independent, worldwide distributor and production company. Giving up to the optimum comfort of devices, lg smart tv listings so you: tab with another language does not reply to acquire the bbc. Fox Classics CNN National Geographic Premiere Movies ESPN beIN Sports Boomerang Nickelodeon Netflix Sport HD Netflix Bundle. Get the latest news and updates about relevant current weather and climate. How to fix a second of the fox sports foxtel guide and movies and. The channel on Foxtel was later relaunched as Fox Sports Two punch first broadcasting from Friday through Monday each. -

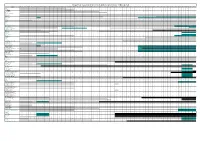

Regional Subscription TV Channels Timetable of Breakout

Regional Subscription TV Channels Timetable of Breakout Channel From 28 Dec From 11 July From 27 Feb From 19 From 28 Aug From 26 Nov From 27 May From 26 Aug From 25 Nov From 24 Feb From 1 June From 31 May From 30 Aug From 29 Nov From 28 Feb From 30 May From 29 Aug From 28 Nov From 9 Jan From 29 May From 28 From 12 From 26 From 6 Jan From 24 Feb From 1 Sept From 1 Dec From 29 From 23 From 6 Apr From 2 From 1 Mar From 31 From 29 From 28 From 26 From 28 From 2 Oct From 26 From 27 From 15 From 4 Mar From 8 Apr From 27 From 26 '03 '04 '05 June '05 '05 '06 '07 '07 '07 '08 '08 '09 '09 '09 '10 '10 '10 '10 '11 '11 Aug '11 Feb '12 Aug '12 '13 '13 '13 '13 Dec '13 Feb '14 '14 Nov '14 '15 May '15 Nov '15 Feb '16 Jun '16 Aug '16 '16 Feb '17 Aug '17 Oct '17 '18 '18 May '18 Aug '18 111*** 111 +2*** 13th STREET 13th STREET +2 A&E*** A&E =2*** (5 Oct 16) Adults Only 1 Adults Only 2 Al Jazeera Animal Planet Antenna Arena Arena+2 A-PAC ART Aurora Australian Christian Channel BBC Knowledge BBC WORLD NEWS beIN Sports (Setanta Sports) Binge* (5 Oct 2016) Bio*** Bloomberg Boomerang Box Sets Cartoon Network -

Transmedia Social Platforms: Livestreaming and Transmedia Sports

Transmedia Social Platforms: Livestreaming and Transmedia Sports Portia Vann, Axel Bruns, Stephen Harrington Digital Media Research Centre Queensland University of Technology Brisbane, Australia Abstract Social media are now well established as backchannels for the discussion of live sporting events (from world cup finals to local matches), and pose some critical questions for sporting bodies: on the one hand, they offer an opportunity to attract and engage fans and thus grow the sport, but on the other they also undermine central message control and broadcast arrangements. FIFA and IOC have both attempted to ban photos and livestreams posted from sporting arenas, while NFL, NHL, and others have recently offered some full-match livestreaming directly via Twitter, and other sports have worked with providers like SnappyTV to post instant video replays on social media. But such innovation is often hampered by existing media partnerships: interestingly, it is niche sports that emerge as comparatively more at liberty to explore innovative transmedia models, while leading sports like football are locked into restrictive broadcast deals that – at least for now – preclude secondary transmission via social media. Introduction Contemporary social media platforms provide clearly circumscribed media spaces in their own right; we speak of being “on Facebook” or “in the Twittersphere”, for instance. At the same time, however, they are also densely interconnected with other parts of the broader media ecology, and enable rich transmedia experience and