Idealism, Materialism, and Biology in the Analysis of Cultural Evolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Materialism and Behavior Analysis: an Introduction to Harris Brian D

The Behavior Analyst 2007, 30, 37–47 No. 1 (Spring) Cultural Materialism and Behavior Analysis: An Introduction to Harris Brian D. Kangas University of Florida The year 2007 marks the 80th anniversary of the birth of Marvin Harris (1927–2001). Although relations between Harris’ cultural materialism and Skinner’s radical behaviorism have been promulgated by several in the behavior-analytic community (e.g., Glenn, 1988; Malagodi & Jackson, 1989; Vargas, 1985), Harris himself never published an exclusive and comprehensive work on the relations between the two epistemologies. However, on May 23rd, 1986, he gave an invited address on this topic at the 12th annual conference of the Association for Behavior Analysis in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, entitled Cultural Materialism and Behavior Analysis: Common Problems and Radical Solutions. What follows is the publication of a transcribed audio recording of the invited address that Harris gave to Sigrid Glenn shortly after the conference. The identity of the scribe is unknown, but it has been printed as it was written, with the addendum of embedded references where appropriate. It is offered both as what should prove to be a useful asset for the students of behavior who are interested in the studyofcultural contingencies, practices, and epistemologies, and in commemoration of this 80th anniversary. Key words: cultural materialism, radical behaviorism, behavior analysis Cultural Materialism and Behavior Analysis: Common Problems and Radical Solutions Marvin Harris University of Florida Cultural materialism is a research in rejection of mind as a cause of paradigm which shares many episte- individual human behavior, radical mological and theoretical principles behaviorism is not radically behav- with radical behaviorism. -

Translation: a Transcultural Activity

Translation: A transcultural activity Andrea Rossi the meaning of a source-language text through an “colere ”, which means to tend to the earth and Consultant in Medical Writing, equivalent target-language text”. 3 The Cambridge grow, or to cultivate and nurture. 8 Culture Communications, and Scientific Affairs, Nyon, definition is “something that is translated, or the encompasses the social behaviour and norms Switzerland process of translating something, from one found in human societies, as well as the know - language to another”. 4 Others define the same ledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and activity as “an act through which the content of a habits of the individuals in these groups. 9 The Correspondence to: text is transferred from the source language into intangible cultural heritage of each society Andrea Rossi the target language”, “a mental activity in which includes science, together with practices of R.te de St. Cergue, 6 the meaning of given linguistic discourse is political organisation and social institutions, 1260 Nyon rendered from one language to another”, or “the mythology, philosophy, and literature. 10 Humans Switzerland act of transferring the linguistic entities from one acquire culture through the processes of +41 793022845 language into their equivalents into another enculturation and socialisation, resulting in the [email protected] language”. 5 diversity of cultures across societies. In contrast to other languages, English When writing about health, translation of distinguishes between translating (a written text) scientific texts plays a special role aimed at public Abstract and interpreting (oral or signed communication education and prevention of diseases as well as Effective communication is the goal of any between users of different languages). -

Culture and Materialism : Raymond Williams and the Marxist Debate

CULTURE AND MATERIALISM: RAYMOND WILLIAMS AND THE MARXIST DEBATE by David C. Robinson B.A. (Honours1, Queen's University, 1988 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS (COMMUNICATIONS) in the ,Department of Communication @ David C. Robinson 1991 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY July, 1991 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME: David Robinson DEGREE: Master of Arts (Communication) TITLE OF THESIS: Culture and Materialism: Raymond Williams and the Marxist Debate EXAMINING COMMITTEE: CHAIR: Dr. Linda Harasim Dr. Richard S. Gruneau Professor Senior Supervisor Dr. Alison C. M. Beale Assistant Professor Supervisor " - Dr. Jerald Zaslove Associate Professor Department of English Examiner DATE APPROVED: PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis or dissertation (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Dissertation: Culture and Materialism: Raymond Williams and the Marxist Debate Author : signature David C. -

The Joint Commission: Cultural Diversity

The Joint Commission: Cultural Diversity Cultural Diversity Lesson Information Purpose To provide healthcare workers with information to increase their knowledge and to help them meet the requirements of The Joint Commission, Occupational Safety & Health Administration, and other regulatory bodies, with the goal of providing safe, competent, and quality patient care. Abstract America is a nation of immigrants. Most Americans' ancestors came from other countries with different languages, customs, and systems of belief. Showing respect for your patients' cultural, spiritual, and psychosocial values demonstrates cultural competency.1 Cultural competency enables healthcare workers to understand their patient's expectations about the care, treatment, and services they receive. This lesson briefly describes the cultural differences that you may encounter when providing care to patients. Objectives Upon completion of this lesson, you will be able to: 1. Define the terms related to culture. 2. Recognize cultural differences among Americans. 3. List interventions that healthcare workers can use to meet the needs of culturally diverse patients. Consultants Contributors Dana Armstrong, RN, MSN Senior Clinical Systems Analyst Mississippi Baptist Health Systems Jackson, Mississippi Reviewers Jodi Nili, RN Quality Management Coordinator Community Regional Medical Center Fresno, California Stephanie Wiedenhoeft, RN, CPHRM, CPHQ Risk Manager Community Medical Centers Fresno, California Copyright © 2016 Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. All rights reserved. Except as specifically permitted herein, no part of this product may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including input into or storage in any information system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Forms and Figures may be displayed and may be reproduced in print form for instructional purposes only, provided a proper copyright notice appears on the last page of each print-out. -

Globalization, World Culture and the Sociology of Taste: Patterns of Cultural Choice in Cross-National Perspective

Globalization, World Culture And The Sociology Of Taste: Patterns Of Cultural Choice In Cross-National Perspective Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Lizardo, Omar Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 11:28:29 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/193871 1 GLOBALIZATION, WORLD CULTURE AND THE SOCIOLOGY OF TASTE: PATTERNS OF CULTURAL CHOICE IN CROSS-NATIONAL PERSPECTIVE By Omar Lizardo _________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For The Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College University of Arizona 2006 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Omar Lizardo entitled Globalization, World Culture And The Sociology Of Taste: Patterns Of Cultural Choice In Cross-National Perspective and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 08/18/06 Ronald L. Breiger _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 08/18/06 Kieran Healy _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 08/18/06 Erin Leahey Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

Sample IDI Intercultural Development Plan (IDP)

Intercultural Development Inventory® Intercultural Development Plan Prepared for: Carl M , Example Group Prepared by: IDI Qualified Administrator, IDI, LLC The Intercultural Development Inventory® (IDI®) is protected by copyright and is the proprietary IDI, LLC property of Mitchell R. Hammer, Ph.D., and IDI LLC. Intercultural Development Inventory and IDI are registered trademarks of Mitchell R. Hammer, Ph.D., and IDI, LLC. You may not use, copy, http://idiinventory.com/ display, distribute, modify, or reproduce any of the trademarks found in this Report except as [email protected] expressly authorized by IDI, LLC. Carl M , Example Group Page | 2 Your Intercultural Development Plan (IDP) Completing the Intercultural Development Inventory® (IDI®) and reviewing your own IDI Individual Profile Report provides key insights into how you make sense of cultural differences and commonalities. The next step is to systematically increase your intercultural competence—from where you are to where want to be—by designing and implementing your own Intercultural Development Plan® (IDP®). This IDP is specifically customized to your own IDI profile results and is an effective way for you to increase your skills in navigating cultural differences. After completing your IDP, you may consider taking the IDI again to determine your progress in increasing your intercultural competence. Should you select this option, a second customized IDP would then be produced based on your most recent IDI profile results, thus providing further intercultural development. By completing your Individual Development Plan, you can: • Gain insights concerning intercultural challenges you are facing and identify intercultural competence development goals that are important for you, • Gain increased understanding of how your Developmental Orientation impacts how you perceive and respond to cultural differences and commonalities, and • Identify and engage in targeted, developmental efforts that increase your intercultural competence in bridging across diverse communities. -

Bhagat Unfolds Multicultural Realities Through 2 States Arvind Jadhav, M.A

Bhagat Unfolds Multicultural Realities through 2 States Arvind Jadhav, M.A. (Eng.), NET, M.A. (Ling.), Ph.D. Scholar ==================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 13:8 August 2013 ==================================================================== Abstract ‘Culture’ can be studied through literature and ‘literature’ can be well appreciated by cultural understanding, I propose. This paper focuses on the multiculturalism in fiction with reference to contemporary author Chetan Bhagat’s 2 States: The Story of My Marriage (Published in 2009). It deals with how multicultural ground realities affect ‘Generation-Y’1 greatly. Preliminaries and methodological considerations discuss the background, objective and the scope of the paper, then it clarifies the mono Vs. multiculturalism. Further, after Indian ‘unity in diversity’ sketch, it analyzes the fiction from cultural perspective and ends with the essence. 1. Preliminaries Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 13:8 August 2013 Arvind Jadhav, M.A. (Eng.), NET, M.A. (Ling.), Ph.D. Scholar Bhagat Unfolds Multicultural Realities through 2 States 88 Let’s start with the concept of the ‘Culture’ first. The New Britannica Encyclopaedia (2007: 784) put forth ‘Culture’ as, ‘the integrated pattern of human knowledge, belief and behavior. Culture, thus defined, consists of language, ideas, beliefs, customs, taboos, codes, institutions, tools, techniques, works of art, rituals, ceremonies, and other related components’ This Encyclopaedia (2007: 784) also quotes a classic definition of ‘Culture’ by Burnett Taylor, in his ‘Primitive Culture’ (1871) as ‘culture includes all capabilities and habits acquired by a man as a member of society’ The part ‘… and other related components’ from the first definition and ‘all capabilities and habits acquired by a man as a member of society’ from the second definition include almost every smaller aspect of society and its integrated or recurrent pattern. -

A Workable Concept for (Cross-)Cultural Psychology?

Unit 2 Theoretical and Methodological Issues Article 14 Subunit 1 Conceptual Issues in Psychology and Culture 9-1-2015 Is “Culture” a Workable Concept for (Cross- )Cultural Psychology? Ype Poortinga Tilburg University, [email protected] I would like to thank for comments and debate on a previous draft of this paper: Ron Fischer, Joop de Jong, and cross-cultural psychologists at Tilburg University in the Netherlands and at Victoria University in Wellington, New Zealand. For readers not convinced by the argument in this paper, I may note that several of these, mainly young, cross-cultural researchers insisted that culture should be seen as something real, like the three blind men who are touching parts of one and the same elephant (see footnote 5). This should bode well for the future of the concept of culture and for one prediction of this paper: that “culture” is unlikely to suffer any time soon the fate of ether or generatio spontanea. Recommended Citation Poortinga, Y. (2015). Is “Culture” a Workable Concept for (Cross-)Cultural Psychology?. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1139 This Online Readings in Psychology and Culture Article is brought to you for free and open access (provided uses are educational in nature)by IACCP and ScholarWorks@GVSU. Copyright © 2015 International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology. All Rights Reserved. ISBN 978-0-9845627-0-1 Is “Culture” a Workable Concept for (Cross-)Cultural Psychology? Abstract In this essay three points are addressed: First, despite repeated findings of limited cross-cultural variation for core areas of study, research in cross-cultural psychology continues to be directed mainly at finding differences in psychological functioning. -

Immigration and Acculturation

T h i r d E d i t i o n Shuang Liu, Zala VolČiČ & Cindy Gallois INTRODUCING Intercultural Communication • GLOBAL CULTURES AND CONTEXTS • LIU_aw.indd 6 00_LIU ET AL_FM.indd 3 05/06/2018 13:18 10/11/2018 12:50:50 PM 9 Immigration and Acculturation LEARNING OBJECTIVES At the end of this chapter, you should be able to: • Understand immigration as a major contributor to cultural diversity. • Explain culture shock and reverse culture shock. • Critically review acculturation models. • Identify the communication strategies that facilitate cross-cultural adaptation. 09_LIU ET AL_CH-09.indd 213 13/11/2018 4:02:17 PM 214 Introducing Intercultural Communication INTRODUCTION It goes without saying that our society is becoming more culturally and linguistically diverse by the day. An important contributor to cultural diversity is the migration of people. Some undertake voluntary migration and others are forced to do so: immigrants, refugees, asylum seekers, businesspeople, international students and so on. Globalization and communication technologies not only redefine the mobility of people in contemporary societies, they also delineate new parameters for interpreting immigration. Historically, immigration referred to the restricted cross-border movements of people, emphasizing the permanent relocation and settlement of usually unskilled, often indentured or contracted labourers who were displaced by political turmoil and thus had little option other than resettlement in a new country. Today, growing affluence and the emergence of a new group of skilled and educated people have fuelled a new global movement of migrants who are in search of better economic opportunities, an enhanced quality of life, greater political freedom and higher expectations. -

How Does Our Culture Make Us Similar and Different?

NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 3rd Grade Cultural Diversity Inquiry How Does Our Culture Make Us Similar and Different? © iStock / © yellowcrestmedia. Supporting Questions 1. What is culture? 2. How does history impact cultures around the world today? 3. How are the lives of children similar and different in global communities? THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION- NONCOMMERCIAL- SHAREALIKE 4.0 INTERNATIONAL LICENSE. 1 NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 3rd Grade Cultural Diversity Inquiry How Does Our Culture Make Us Similar and Different? New York State Social 3.5: Communities share cultural similarities and differences across the world. Studies Framework Gathering, Using, and Interpreting Evidence Chronological Reasoning and Causation Key Idea & Practices Comparison and Contextualization Geographic Reasoning Civic Participation Staging the Question Discuss the concept of “culture,” by brainstorming responses to the question, “what does culture look like?” Supporting Question 1 Supporting Question 2 Supporting Question 3 Research Understand Understand Assess What is culture? How does history impact cultures How are the lives of children similar around the world today? and different in global communities? Formative Formative Formative Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task List key details from text and Identify examples of historical Write a paragraph that compares and illustrations to answer the supporting influences on present-day cultures contrasts aspects of daily life for kids in question. around the world on a three-column several world communities. chart. Featured Source Featured Sources Featured Source Source A: “Discovering Culture” Source A: “Brazil Today—Carnaval! The Source A: Day in the Life Celebration of Brazil” Source B: Excerpts from Exploring Countries: France Source C: “The Ancient Art of Rangoli” Summative ARGUMENT How does our culture make us similar and different? Construct an argument supported with Performance evidence that addresses the compelling question. -

MODULE 1. Unit 2. INTERCULTURAL COMPETENCE and SENSITIVITY to DIVERSITY Additional Information

Training packages for health professionals to improve access and quality of health services for migrants and ethnic minorities, including the Roma MEM‐TP MODULE 1. Unit 2. INTERCULTURAL COMPETENCE AND SENSITIVITY TO DIVERSITY Additional Information Prepared by: Ainhoa Rodriguez and Olga Leralta Andalusian School of Public Health © European Union, 2015 For any reproduction of textual and multimedia information which are not under the © of the European Union, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders. © Cover Illustrations: Observatorio de la Infancia de Andalucía, Escuela Andaluza de Salud Pública. Junta de Andalucía. Migrants & Ethnic Minorities Training Packages Funded by the European Union in the framework of the EU Health Programme (2008‐2013) in the frame of a service contract with the Consumer, Health, Agriculture and Food Executive Agency (Chafea) acting under the mandate from the European Commission. The content of this report represents the views of the Andalusian School of Public Health (EASP) and is its sole responsibility; it can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Commission and/or Chafea or any other body in the European Union. The European Commission and/or Chafea do not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this report, nor do they accept responsibility for any use made by third parties thereof. 1 September, 2015 MEM‐TP Module 1, Unit 2: Additional Information 1. Multiculturalism, Interculturalism, Intercultural Dialogue, Cultural Competence, Intercultural Competence, Difference Sensitivity and Diversity Sensitivity: Concepts A broad theoretical discussion1,2,3,4,5 related to “multiculturalism” and “interculturalism” is ongoing. Some authors6,7 conceive both concepts as differentiated. -

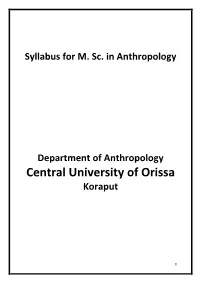

M.Sc. in Anthropology Syllabus

Syllabus for M. Sc. in Anthropology Department of Anthropology Central University of Orissa Koraput 0 M.Sc. in ANTHROPOLOGY Semester-I: Course Course Code Title Credits Full Mark No. 1 ANT – C 311 Biological Anthropology -I 4 100 2 ANT – C 312 Socio-Cultural Anthropology 4 100 3 ANT – C 313 Archaeological Anthropology 4 100 & Museology 4 ANT – C 314 Research Methods 4 100 5 ANT – C 315 Tribes in India 2 100 6 ANT – C 316 General Practical – I 2 100 Semester-II: Course Course Code Title Credits Full Mark No. 7 ANT – C 321 Biological Anthropology -II 4 100 8 ANT – C 322 Theories of Society and 4 100 Culture 9 ANT – C 323 Pre- and Proto- History of 4 100 India, Africa and Europe 10 ANT – C 324 Indian Anthropology 4 100 11 ANT – C 325 Peasants in India 2 100 12 ANT – C 326 General Practical – II 2 100 1 Semester-III: (GROUP – A: Physical / Biological Anthropology) Course Course Code Title Credits Full No. Mark 13 ANT – C 331 Anthropological Demography 4 100 14 ANT – C 332 Field Work Training 2 100 15 ANT – C 333 Human Ecology: Biological & Cultural 2 100 dimensions 16 ANT – C 334 ‘A’ Medical Genetics 4 100 17 ANT – C 335 ‘A’ Practical in Biological Anthropology - I 4 100 18 ANT – E1 336 ‘A’ Growth and Nutrition, OR 4 100 ANT – E2 336 ‘A’ Forensic Anthropology – I, OR ANT – E3 336 ‘A’ Environmental Anthropology Students can choose one Extra Electives offered by Department and one Allied Electives from other Subjects in 3rd Semester Semester-III: (GROUP – B: Socio - Cultural Anthropology) Course Course Code Title Credits Full Mark No.