FEIS Appendices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

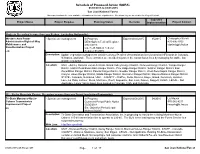

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 01/01/2015 to 03/31/2015 San Juan National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 01/01/2015 to 03/31/2015 San Juan National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring in more than one Region (excluding Nationwide) Western Area Power - Special use management In Progress: Expected:03/2015 05/2015 Christopher Wehrli Administration Right-of-Way DEIS NOA in Federal Register 435-896-1053 Maintenance and 09/27/2013 [email protected] Reauthorization Project Est. FEIS NOA in Federal EIS Register 01/2015 Description: Update vegetation management activities along 278 miles of transmission lines located on NFS lands in Colorado, Nebraska, and Utah. These activities are intended to protect the transmission lines by managing for stable, low growth vegetation. Location: UNIT - Ashley National Forest All Units, Grand Valley Ranger District, Norwood Ranger District, Yampa Ranger District, Hahns Peak/Bears Ears Ranger District, Pine Ridge Ranger District, Sulphur Ranger District, East Zone/Dillon Ranger District, Paonia Ranger District, Boulder Ranger District, West Zone/Sopris Ranger District, Canyon Lakes Ranger District, Salida Ranger District, Gunnison Ranger District, Mancos/Dolores Ranger District. STATE - Colorado, Nebraska, Utah. COUNTY - Chaffee, Delta, Dolores, Eagle, Grand, Gunnison, Jackson, Lake, La Plata, Larimer, Mesa, Montrose, Routt, Saguache, San Juan, Dawes, Daggett, Uintah. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Linear transmission lines located in Colorado, Utah, and Nebraska. R2 - Rocky Mountain Region, Occurring in more than one Forest (excluding Regionwide) Tri-State Montrose-Nucla- - Special use management In Progress: Expected:08/2015 04/2016 Liz Mauch Cahone Transmission Comment Period Public Notice 970-242-8211 Improvement Project 05/05/2014 [email protected] EA Est. -

36 CFR Ch. II (7–1–13 Edition) § 294.49

§ 294.49 36 CFR Ch. II (7–1–13 Edition) subpart shall prohibit a responsible of- Line Includes ficial from further restricting activi- Colorado roadless area name upper tier No. acres ties allowed within Colorado Roadless Areas. This subpart does not compel 22 North St. Vrain ............................................ X the amendment or revision of any land 23 Rawah Adjacent Areas ............................... X 24 Square Top Mountain ................................. X management plan. 25 Troublesome ............................................... X (d) The prohibitions and restrictions 26 Vasquez Adjacent Area .............................. X established in this subpart are not sub- 27 White Pine Mountain. ject to reconsideration, revision, or re- 28 Williams Fork.............................................. X scission in subsequent project decisions Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, Gunnison National Forest or land management plan amendments 29 Agate Creek. or revisions undertaken pursuant to 36 30 American Flag Mountain. CFR part 219. 31 Baldy. (e) Nothing in this subpart waives 32 Battlements. any applicable requirements regarding 33 Beaver ........................................................ X 34 Beckwiths. site specific environmental analysis, 35 Calamity Basin. public involvement, consultation with 36 Cannibal Plateau. Tribes and other agencies, or compli- 37 Canyon Creek-Antero. 38 Canyon Creek. ance with applicable laws. 39 Carson ........................................................ X (f) If any provision in this subpart -

Profiles of Colorado Roadless Areas

PROFILES OF COLORADO ROADLESS AREAS Prepared by the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region July 23, 2008 INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ARAPAHO-ROOSEVELT NATIONAL FOREST ......................................................................................................10 Bard Creek (23,000 acres) .......................................................................................................................................10 Byers Peak (10,200 acres)........................................................................................................................................12 Cache la Poudre Adjacent Area (3,200 acres)..........................................................................................................13 Cherokee Park (7,600 acres) ....................................................................................................................................14 Comanche Peak Adjacent Areas A - H (45,200 acres).............................................................................................15 Copper Mountain (13,500 acres) .............................................................................................................................19 Crosier Mountain (7,200 acres) ...............................................................................................................................20 Gold Run (6,600 acres) ............................................................................................................................................21 -

Summary of Public Comment, Appendix B

Summary of Public Comment on Roadless Area Conservation Appendix B Requests for Inclusion or Exemption of Specific Areas Table B-1. Requested Inclusions Under the Proposed Rulemaking. Region 1 Northern NATIONAL FOREST OR AREA STATE GRASSLAND The state of Idaho Multiple ID (Individual, Boise, ID - #6033.10200) Roadless areas in Idaho Multiple ID (Individual, Olga, WA - #16638.10110) Inventoried and uninventoried roadless areas (including those Multiple ID, MT encompassed in the Northern Rockies Ecosystem Protection Act) (Individual, Bemidji, MN - #7964.64351) Roadless areas in Montana Multiple MT (Individual, Olga, WA - #16638.10110) Pioneer Scenic Byway in southwest Montana Beaverhead MT (Individual, Butte, MT - #50515.64351) West Big Hole area Beaverhead MT (Individual, Minneapolis, MN - #2892.83000) Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness, along the Selway River, and the Beaverhead-Deerlodge, MT Anaconda-Pintler Wilderness, at Johnson lake, the Pioneer Bitterroot Mountains in the Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest and the Great Bear Wilderness (Individual, Missoula, MT - #16940.90200) CLEARWATER NATIONAL FOREST: NORTH FORK Bighorn, Clearwater, Idaho ID, MT, COUNTRY- Panhandle, Lolo WY MALLARD-LARKINS--1300 (also on the Idaho Panhandle National Forest)….encompasses most of the high country between the St. Joe and North Fork Clearwater Rivers….a low elevation section of the North Fork Clearwater….Logging sales (Lower Salmon and Dworshak Blowdown) …a potential wild and scenic river section of the North Fork... THE GREAT BURN--1301 (or Hoodoo also on the Lolo National Forest) … harbors the incomparable Kelly Creek and includes its confluence with Cayuse Creek. This area forms a major headwaters for the North Fork of the Clearwater. …Fish Lake… the Jap, Siam, Goose and Shell Creek drainages WEITAS CREEK--1306 (Bighorn-Weitas)…Weitas Creek…North Fork Clearwater. -

Colorado Roadless Areas

MAP 3 MAP 3 Colorado Roadless Areas CRA acres 135 Kreutzer-Princeton 43,300 255 Blackhawk Mountain 17,500 Rounded 232 Colorado Roadless Area Names 136 Little Fountain Creek 7,700 256 East Animas 16,900 233 to nearest Platte River 100 acres 137 Lost Creek East 14,900 257 Fish Creek 13,500 Wilderness Arapaho-Roosevelt National Forest 4 138 Lost Creek South 5,900 258 Florida River 5,700 246 236 1 Bard Creek 22,800 139 Lost Creek West 14,400 259 Graham Park 17,800 23 2 Byers Peak 10,200 ** Map Key ** 140 Methodist Mountain 6,900 260 HD Mountains 25,000 248 232 3 Cache La Poudre Adjacent Area 3,000 226 243 Mount 141 Mount Antero 38,700 261 Hermosa 148,100 234 4 Cherokee Park 7,600 Major Roads Zirkel 21 5 Comanche Peak Adjacent Areas 44,200 142 Mount Elbert 22,100 262 Lizard Head Adjacent 5,800 Wilderness 23 249 244 6 Copper Mountain 13,200 143 Mount Evans 15,400 263 Piedra Area Adjacent 40,800 247 236 Rawah 25 76 10 7 Crosier Mountain 7,300 144 Mount Massive 1,400 Wilderness 264 Runlett Park 5,600 9 8 Gold Run 6,600 Colorado Roadless Areas 11 145 Pikes Peak East 13,700 265 Ryman 8,700 235 5 3 9 Green Ridge -East 26,600 146 Pikes Peak West 13,900 266 San Miguel 64,100 C3ache La Poudre 10 Green Ridge -West 13,700 5 3 Wilderness 147 Porphyry Peak 3,900 253 5 11 Grey Rock 12,100 267 South San Juan Adjacent 34,900 National Forest System Wilderness & 5 Comanche Peak 27 148 Puma Hills 8,800 268 Storm Peak 57,600 239 23 Wilderness 12 Hell Canyon 5,800 230 5 13 Indian Peaks Adjacent Areas 28,600 149 Purgatoire 16,800 269 Treasure Mountain 22,500 Other -

Pioneers, Prospectors and Trout a Historic Context for La Plata County, Colorado

Pioneers, Prospectors and Trout A Historic Context For La Plata County, Colorado By Jill Seyfarth And Ruth Lambert, Ph.D. January, 2010 Pioneers, Prospectors and Trout A Historic Context For La Plata County, Colorado Prepared for the La Plata County Planning Department State Historical Fund Project Number 2008-01-012 Deliverable No. 7 Prepared by: Jill Seyfarth Cultural Resource Planning PO Box 295 Durango, Colorado 81302 (970) 247-5893 And Ruth Lambert, PhD. San Juan Mountains Association PO Box 2261 Durango, Colorado 81302 January, 2010 This context document is sponsored by La Plata County and is partially funded by a grant from the Colorado State Historical Fund (Project Number 2008-01-012). The opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of the staff of the Colorado State Historical Fund. Cover photographs: Top-Pine River Stage Station. Photo Source: La Plata County Historical Society-Animas Museum Photo Archives. Left side-Gold King Mill in La Plata Canyon taken in about1936. Photo Source Plate 21, in U.S.Geological Survey Professional paper 219. 1949 Right side-Local Fred Klatt’s big catch. Photo Source La Plata County Historical Society- Animas Museum Photo Archives. Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 New Frontiers................................................................................................................ 3 Initial Exploration ............................................................................................ -

A Statewide Assessment of Wildlife Linkages Phase I Report

LINKINLINKINGG COLCOLORADO'SORADO'S LLANDSCAPES:ANDSCAPES: AA STATEWIDESTATEWIDE ASSESSMENTASSESSMENT OFOF WILDLIFEWILDLIFE LINKALINKAGESGES PHASEPHASE II REPORTREPORT March 2005 © 2005 John Fielder In collaboration with: For additional information contact: Julia Kintsch, Program Director 1536 Wynkoop Suite 309 Denver, Colorado 80202 Tel: 720-946-9653 [email protected] www.RestoreTheRockies.org TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Maps List of Figures Acknowledgements Executive Summary .........................................................................................1 PART I: Introduction A. Project Description and Development ...................................................2 PART II: Methods A. Focal Species Approach.........................................................................5 B. Workshops ...........................................................................................10 Data Compilation and Linkage Prioritization................................15 C. Species Connectivity Modeling ...........................................................17 Modeling Approach .......................................................................17 Aquatic Fragmentation.........................................................................31 PART III: Workshop and Modeling Prioritization Results A. Summary of Workshop Results ...........................................................32 Results by Species Group ..............................................................48 B. Modeling Results .................................................................................97 -

470 Part 294—Special Areas

§ 293.17 36 CFR Ch. II (7–1–20 Edition) (iii) The portage from Back Bay to under appropriate conditions deter- Pipestone Bay of Basswood Lake. mined by the Chief, Forest Service. (iv) The portages from Fall Lake to (b) Grazing of domestic livestock, de- Newton Lake to Pipestone Bay of Bass- velopment of water storage projects wood Lake. which do not involve road construc- (v) The portage from Vermilion Lake tion, and improvements necessary for to Trout Lake. the protection of the National Forests (2) The Forest Service may authorize, may be permitted, subject to such re- by special use permit, the use of motor strictions as the Chief, Forest Service, vehicles to transport watercraft over deems desirable. Within Primitive the following portages: Areas, when the use is for other than (i) Four Mile Portage From Fall administrative needs of the Forest Lake to Hoist Bay of Basswood Lake. Service, use by other Federal agencies (ii) Vermilion Lake to Trout Lake. when authorized by the Chief, and in (iii) Prairie Portage from Sucker emergencies, the landing of aircraft Lake to Basswood Lake and the use of motorboats are prohib- (iv) Loon River to Loon Lake and ited on National Forest land or water from Loon Lake to Lac La Croix. unless such use by aircraft or motor- (c) Snowmobile use. (1) A snowmobile boats has already become well estab- is defined as a self-propelled, motorized lished, the use of motor vehicles is pro- vehicle not exceeding forty inches in hibited, and the use of other motorized width designed to operate on ice and equipment is prohibited except as au- snow, having a ski or skiis in contact thorized by the Chief. -

SAN JUAN NATIONAL FOREST Baldy (20,300 Acres)

SAN JUAN NATIONAL FOREST Baldy (20,300 acres) ....................................................................................................................... 3 Blackhawk Mountain (17,500 acres) .............................................................................................. 4 East Animas (16,900 acres) ............................................................................................................ 5 Fish Creek (13,500 acres) ............................................................................................................... 6 Florida River (5,700 acres) ............................................................................................................. 8 Graham Park (17,800 acres) ........................................................................................................... 9 HD Mountains (25,000 acres) ....................................................................................................... 11 Hermosa (148,100 acres) .............................................................................................................. 13 Lizard Head Adjacent (5,800 acres) ............................................................................................. 16 Piedra Area Adjacent (40,800 acres) ............................................................................................ 17 Runlett Park (5,600 acres) ............................................................................................................. 20 Ryman (8,700 acres) .................................................................................................................... -

Special Areas and Unique Landscapes

SPECIAL AREAS AND UNIQUE LANDSCAPES This section of the Plan includes specific management direction for a number of special areas possessing unique characteristics. Some special areas have specific Congressional or administrative designations, including: • Wilderness Areas and Wilderness Study Areas (WSAs); • Inventoried Roadless Areas (IRAs); • Proposed Wilderness; • Wild and Scenic Rivers (WSRs); • Scenic, Historic, and Backcounty Byways; • National Recreation and Scenic Trails, and National Historic Trails; • Research Natural Areas (RNAs); • Areas of Critical Environmental Concern (ACECs); • Archeological Areas; • Wild Horse Herd Management Areas; • Wildlife Habitat Management Areas (HMAs); and • Special Botanical Areas. Other areas with unique characteristics that do not require special designation by Congress, or administrately by the USFS or BLM, are included in MA 2 as “Unique Landscapes.” These include: Dolores River Canyon; Rico; McPhee; Mesa Verde Escarpment; HD Mountains; and Silverton. SPECIAL AREAS AND UNIQUE LANDSCAPES ■ STRATEGY ■ Part 2 ■ DLMP ■ Volume 2 ■ Page 163 Figure 20 - Special Areas and Unique Landscapes Page 164 Page San Juan Public Lands ■ Volume Special Areas and Unique Landscapes NUCLA 2 ■ DLMP RIDGWAY NORWOOD ■ Legend Part Special Areas and Unique Landscapes Bureau of Land Management 2 LAKE CITY Bureau of Reclamation ■ SAWPIT Colorado Division of Wildlife STRATEGY National Forest Indian Reservation National Park Service Patented Lands ■ OPHIR State Lands CREEDE SPECIAL Wilderness SILVERTON Piedra Area DOVE CREEK USFS/BLM - Ranger Districts / Field Office Boundary AREAS Cities and Towns Major Lakes RICO Major Rivers AND State & Federal Highways UNIQUE LANDSCAPES DOLORES CORTEZ MANCOS DURANGO PAGOSA SPRINGS BAYFIELD TOWAOC IGNACIO The USFS and BLM attempt to use the most current and complete geospatial data available. -

SJCA Kicks Off Wildlife Program Wolves & Bighorns a Priority

Photo: Tom Skyes Tom Photo: SJCA Kicks off Wildlife Program Wolves & Bighorns a priority Plus: Defending the HD Mountains Four Corners Solar Projects Fall/Winter 2020 DEAR SUPPORTERS, Many of us probably can’t wait to wave adios to 2020. We’ve experienced unprecedented turmoil from a virulent pandemic, economic upheaval, political wrangling, and a relentless assault on the bedrock American values of clean air, clean water and public lands. 2021 has a low bar to clear for vast improvements over this year! The election results mean a reversal of course at the federal level on climate policies, federal land management, and a host of pollution and environmental regulations. Election results in New Mexico and Colorado maintained the status quo, and we anticipate continued progress towards renewable energy, greenhouse gas reductions, and wildlife habitat conservation. We look forward to working with the incoming Biden Administration to get back on track addressing the root causes of climate change. In the absence of federal leadership the past four years, we’ve turned to state legislators, governors, and agencies in Colorado and New Mexico to undertake new rules to reduce methane pollution from oil and gas facilities, and to embark upon ambitious climate change goals. Nowhere has seen more rapid change than New Mexico. In just the past year, Public Service Company of New Mexico gained approval to retire the 847-MW coal-fired San Juan Generating Station near Farmington and replace that power with almost 1,000-MW of new large-scale solar and battery storage, all located in northwest New Mexico. -

High Country News Vol. 25.7, Apr. 19, 1993

.. hZt., ...... .,"" tK. SEPia Aprl/19, 1993 VoL 25 No.7 A Paper for People who Care about tbe West One dollar and.fifty cents ..MlCON\£, MR. PRESIOEN'f, TO1\.IE OlI)'G~ TIM~RSUMM\T..." ~~ ~~.- • . .. , ."", Reporter's Notebooks: The way it was at the summit in Portland, Oregon/14, 15 .... nvironmentiilists' euphoria over budget was not the place to rework the times the subsidy it gives the West's ranchers. ~" President Bill Clinton's Western West's approach to public land mining, "Does he have the abilityto say no?" ~ ~ policies came to an abrupt end grazing and logging. Instead, they Western Republicans were allowed by ~ in late March, when the White promised to deliver reform in a package of their constituency to preach free enterprise . .. House pulled public land individual bills. while protecting subsidies to public land reforms from its new budget. The retreat was Rep. George Miller, D-Calif., head of the users. But Western Democrats, whose so quiet the White House wasn't the first to House Committee on Natural Resources, coalition includes city dwellers and envi- announce that grazing fee increases, mining said he has been "waiting for that indepen- ronmentalists, may have more trouble royalties and prohibitions on below-cost tim- dent legislation for 12 years." He also said keeping their base. That is especially true 'ber sales were no longer part.of the because the action was portrayed Clinton budget by the media as having seriously The honor of making that weakened Clinton's ability to announcement fell to Western Clinton flinches institute national reforms.